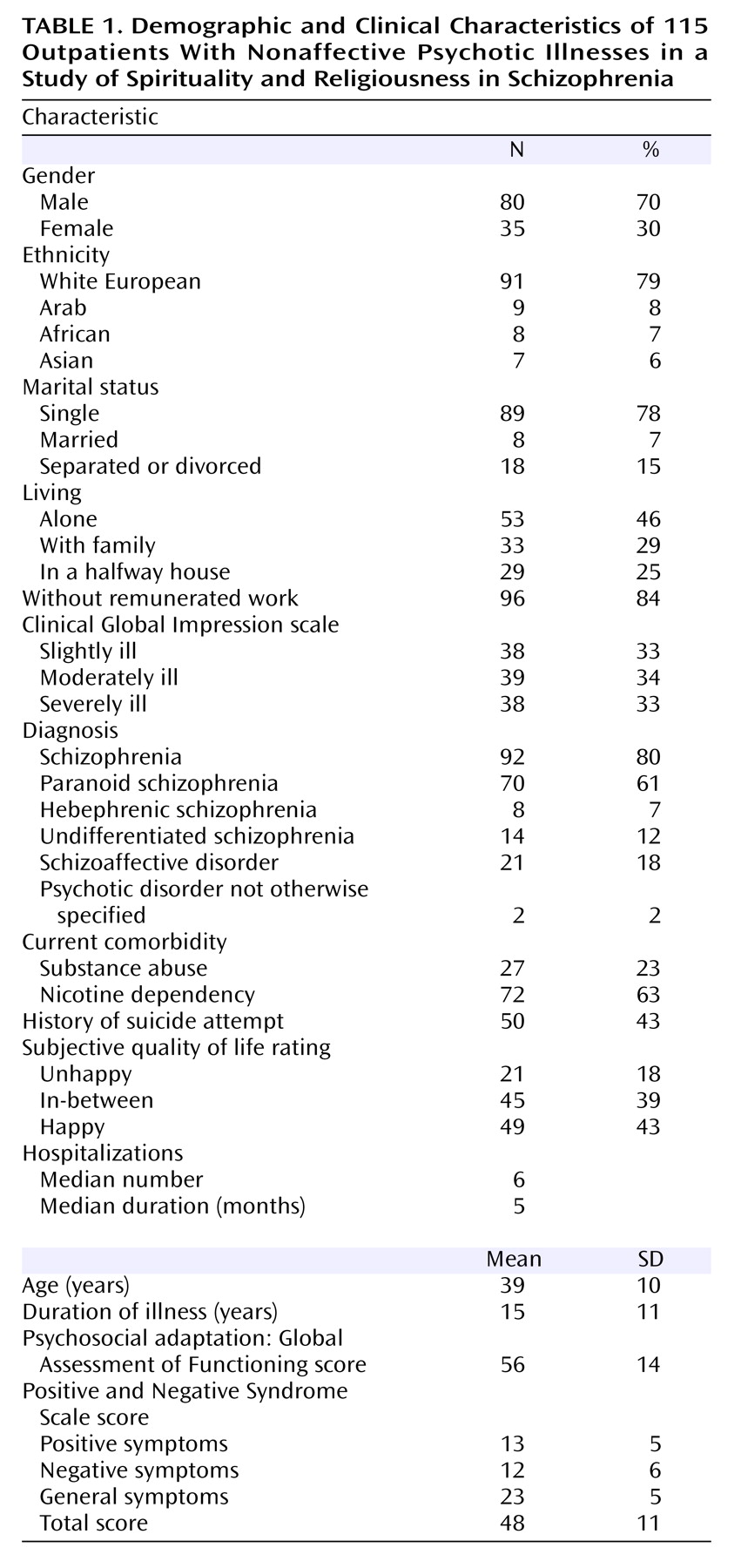

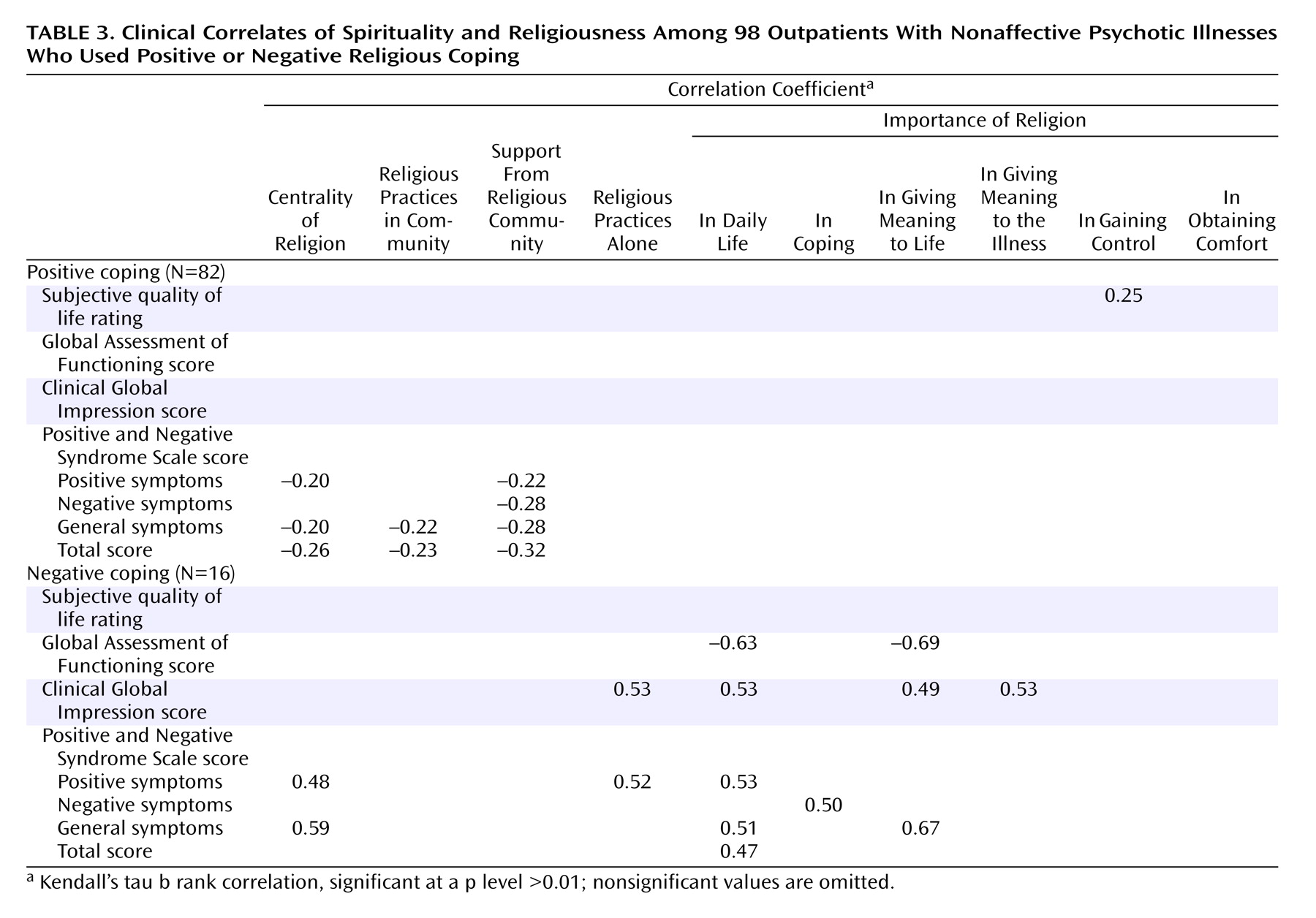

Table 1 summarizes the sample’s demographic and clinical characteristics. The majority of the patients were Christian (61%); 9% came from other traditional religions (Judaism, Islam, and Buddhism), 12% from minority religious movements (for example, esoterism, spiritism, Christian Science, Scientology, or UFOlogy), and 18% had no religious affiliation. Fifty-six percent reported that they never participated in religious practices with other people, 14% did so occasionally, and 30% did so at least once a month. Twenty percent felt they received great support from their religious community and 10% some support. Twenty-four percent reported that they never engaged in any religious practices alone, 14% that they occasionally did so, 10% that they did so every week, and 52% that they did so every day. Religion was important in the lives of 85% of the patients and was absent from or of no importance in the lives of 15%. For nearly half the patients (45%), religion was the most important element in their lives; 78% rated it as being important to essential in day-to-day life, 67% in giving meaning to their lives, 59% in giving meaning to their illness, 60% in helping them cope with their illness, 52% in helping them gain control of their illness, and 63% in giving them comfort. Some patients perceived an antagonism between their religion and medication (12%) or supportive therapy (10%). Most patients (80%) felt at ease in talking about religion with psychiatrists.

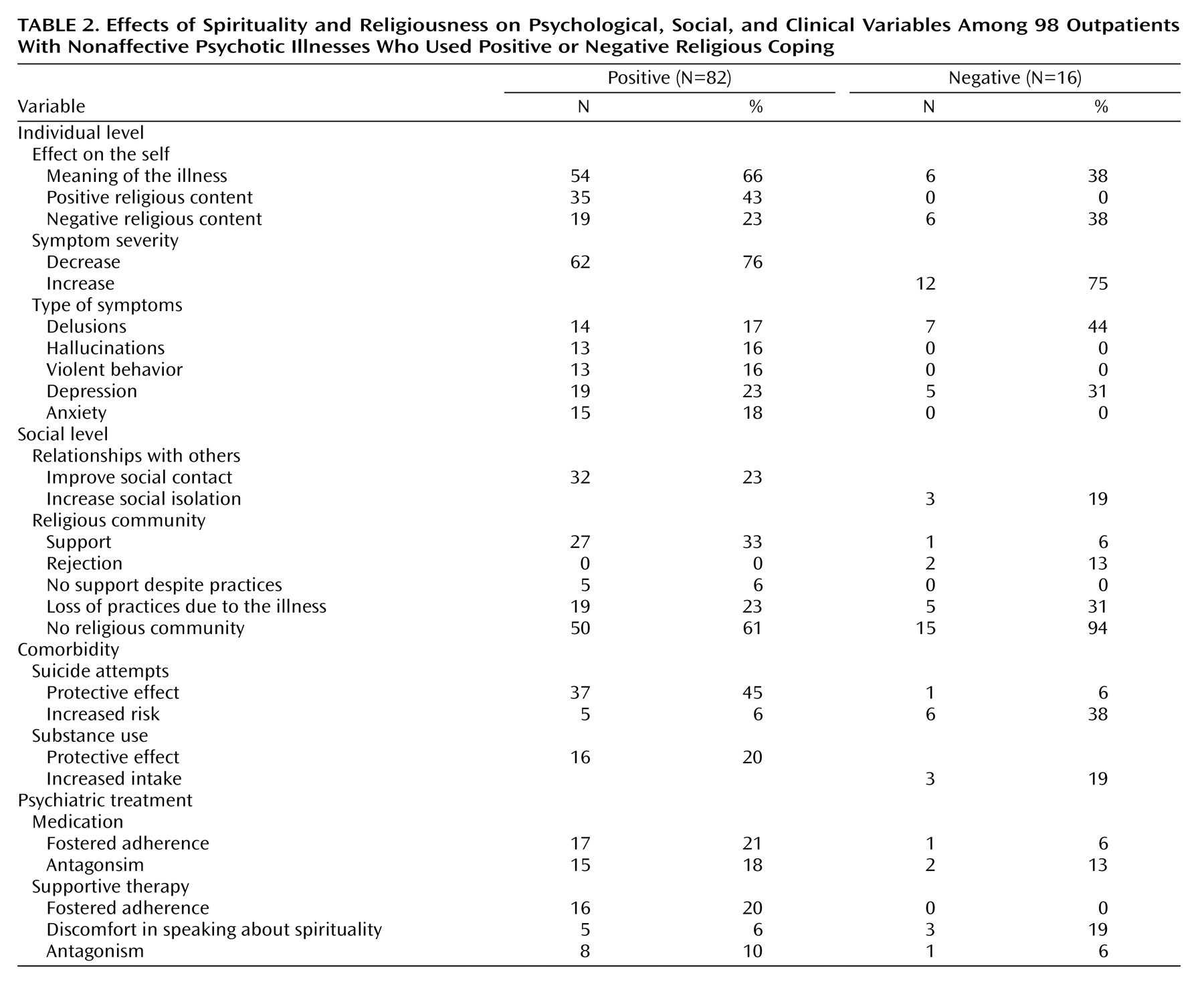

Positive Effects of Religious Coping

Religion was used as a positive way of coping by 71% of patients and as a negative way of coping by 14% of patients. At a psychological level, religion gave these patients a positive sense of self, in terms of hope, comfort, meaning of life, enjoyment of life, love, compassion, self-respect, self-confidence, and so on. For two-thirds of these patients, religion gave meaning to their illness, mainly through positive religious connotations (a grace, a gift, God’s test in order to grow in spiritual life, a spiritual acceptance of suffering, and the like), and less frequently with negative connotations (the devil, demons, God’s punishment, and the like). However, even if those meanings were negative in religious terms, they were positive in psychological terms by fostering an acceptance of the illness or a mobilization of religious resources to cope with the symptoms. For example, one patient said, “I think my illness is God’s punishment for my sins; it gives meaning to what happened to me, so it is less unjust” (30-year-old woman with paranoid schizophrenia). Another said, “I believe that my hallucinations and delusions are due to bad spirits; this gives me an explanation that helps me to lessen my fear and distress, and to stay calm” (30-year-old woman with paranoid schizophrenia). For three-quarters of this coping group, religious coping had a positive impact on positive symptoms (by lessening the emotional or behavioral reactions to delusions and hallucinations, by reducing aggressive behavior, or both), as well as on negative and general symptoms. Two patients who suffered from delusions of persecution expressed this clearly. One said, “I always have a Bible with me. When I feel I am in danger, I read it and I feel I am protected. It helps me to control my violent actions” (26-year-old man with paranoid schizophrenia). The other said, “If you say that God is love, you try to learn to love people. This allows me to distance myself from my problems relating to people, to welcome people” (40-year-old woman with paranoid schizophrenia). A patient who had delusions of control said, “For some time every day, I feel that other people can control me from a distance and that they can do anything they want with me. However, I do not feel anxious like I did before. The Buddhist monk told me it was only my imagination, and he teaches me how to meditate. In this way, I distance myself from this idea of control; I tell myself that it is just a symptom of an illness, that there is nothing true about it and it has no meaning” (20-year-old man with paranoid schizophrenia). A patient who suffered from auditory hallucinations said, “If you tell yourself that you have an eternal life ahead of you, you know that the voices will end, that they are not eternal. Consequently, voices are nothing in fact when they will not always be there” (25-year-old man with paranoid schizophrenia).

Religion may also help in reducing anxiety, depression, and negative symptoms, as illustrated in the following quotations. “I am anxious about meeting people, so beforehand I pray that everything will be OK. Then I am confident in the situation” (50-year-old man with paranoid schizophrenia). “I have no motivation to do anything, so I pray; I offer my suffering to Jesus. This gives me strength and comfort to do things” (60-year-old woman with schizoaffective disorder). “When I feel despair, prayer helps me find peace, strength, and comfort” (49-year-old woman with undifferentiated schizophrenia). “I am spiritual in my heart. My way of meditating is to sing. Breath and spirit are linked. When I sing, I do not feel as depressed, and I am more enthusiastic about doing things” (44-year-old man with paranoid schizophrenia).

At the social level, religion can provide guidelines for interpersonal behavior, leading to reduced aggression and improved social relationships. One patient said, “Believing in Jesus helps me to control my actions. It means not beating my fellow man when he upsets me!” (31-year-old man with paranoid schizophrenia). Another said, “It is difficult for me to communicate with people. I read the Bible and I meditate about love, peace, and forgiveness, and it helps me in my day-to-day relationships with others” (36-year-old man with paranoid schizophrenia).

Despite the subjective importance of religion, only one-third of the patients in the positive coping group actually received social support from a religious community. Some did not receive any support from their communities because of their symptoms, even though they engaged regularly in religious practices, as illustrated in the following quotations. “I’ve gone to church every Sunday since childhood; I listen to the sermon; I do not speak to anyone” (50-year-old man with paranoid schizophrenia). “I am angry with my brothers in Christ because they did not help me at all. Religious teaching helps me, but I haven’t found any warmth in relationships with people. On the contrary, I feel persecuted by them” (31-year-old man with paranoid schizophrenia). “I go to the synagogue every day. I do not tell my friends about my problems, so they cannot stand me” (29-year-old man with paranoid schizophrenia). More often, symptoms hindered religious patients from practicing in their religious communities: “I lived in a religious community for 2 years. Now, I pray alone every day. It is too difficult for me to go to church. When I go to the service, I see dirty things and I feel the devil taking my hand” (48-year-old woman with paranoid schizophrenia). “For 2 years now, I’ve felt so indifferent, without any motivation, that I have given up my involvement in my church. I feel guilty that I’m not involved like other people” (60-year-old woman with schizoaffective disorder).

However, for some patients, religious communities provided precious social support. One patient said, “I am a single woman; I have a lot of problems. At church, I meet a lot of people. It comforts me. I participate in every church activity: the service on Sunday, the intercession prayer group, and I sing in the choir. The pastor and church members pray for me” (39-year-old woman with paranoid schizophrenia).

Religion may play positive and negative roles in the comorbidity that is frequently associated with schizophrenia. Religion may protect against suicide attempts. As one patient said, “When I feel such despair that I want to jump out the window, I think about God. This helps me to live, even if life is so hard sometimes” (41-year-old man with paranoid schizophrenia). However, religion may be a risk factor, even for patients with positive religious coping. As another patient said, “Spirituality is essential in my life; I know that there is life after death. Once, I took medication to die in order to experience death and know what it is like afterward” (36-year-old man with schizoaffective disorder). Religion provided guidelines for some patients that protected them from substance abuse. It may even have oriented them toward a life free of toxic substances. “I felt bad. I smoked a lot of hashish every day. Once I had a religious conversion after a mystical revelation that the way I was behaving was not what God wanted for me” (34-year-old man with paranoid schizophrenia).

Religion may also play a role in decreasing or increasing adherence to psychiatric treatment. Some patients felt that a contradiction existed between religion and psychiatric care. “Psychiatrists say that my mind is disorganized. Medication helps me with that. But I want God to organize my mind. I need a miracle in my life” (26-year-old man with paranoid schizophrenia). On the other hand, psychiatric care may be integrated into religious beliefs when patients give God credit for its existence: “God has provided psychiatrists and medication to heal patients. First I trust God; then, thanks to God, I trust people. It is a great relief for me to be able to trust” (47-year-old man with schizoaffective disorder). Naturally, such beliefs depended mainly on the individuals rather than on the religious community. Indeed, the two patients quoted here were both highly involved in Pentecostal churches.

In some patients’ lives, religious leaders played a key role in the integration of psychiatric care and religious beliefs. One patient described his experience as follows: “Two years ago, I began to hear voices of demons; I believed I was Jesus Christ. I met an exorcist priest. He told me that I could not be Jesus Christ and he taught me the gospel. I met him every week. The voices told me not to take any medication. He told me not to listen to them, that demons are liars. He told me that the medication could help me. Since then, I’ve agreed to take it” (24-year-old man with paranoid schizophrenia).