Data for this report were collected from November 1998 to October 2004.

Symptom Response

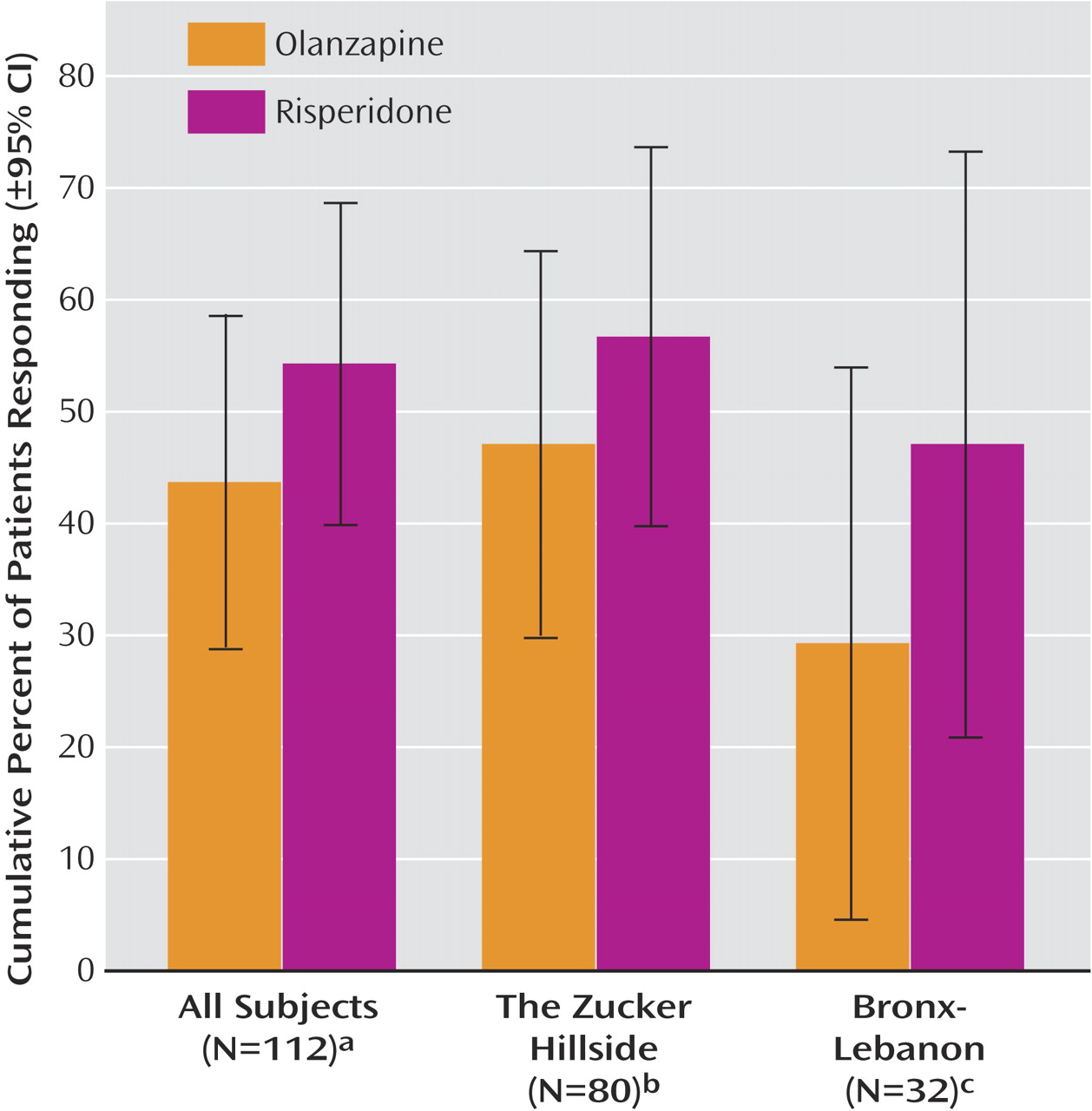

Cumulative response rates by 4 months were similar with olanzapine (43.7%, 95% CI=28.8%–58.6%) and risperidone (54.3%, 95% CI=39.9%–68.7%) (

Figure 2 ). Mean time to response was 10.9 weeks (95% CI=9.7–12.2) with olanzapine and 10.4 weeks (95% CI=9.1–11.7) with risperidone. Mean daily dose at the time of response for subjects who responded to olanzapine was 8.9 mg (SD=5.1) and 3.4 mg (SD=1.2) with risperidone.

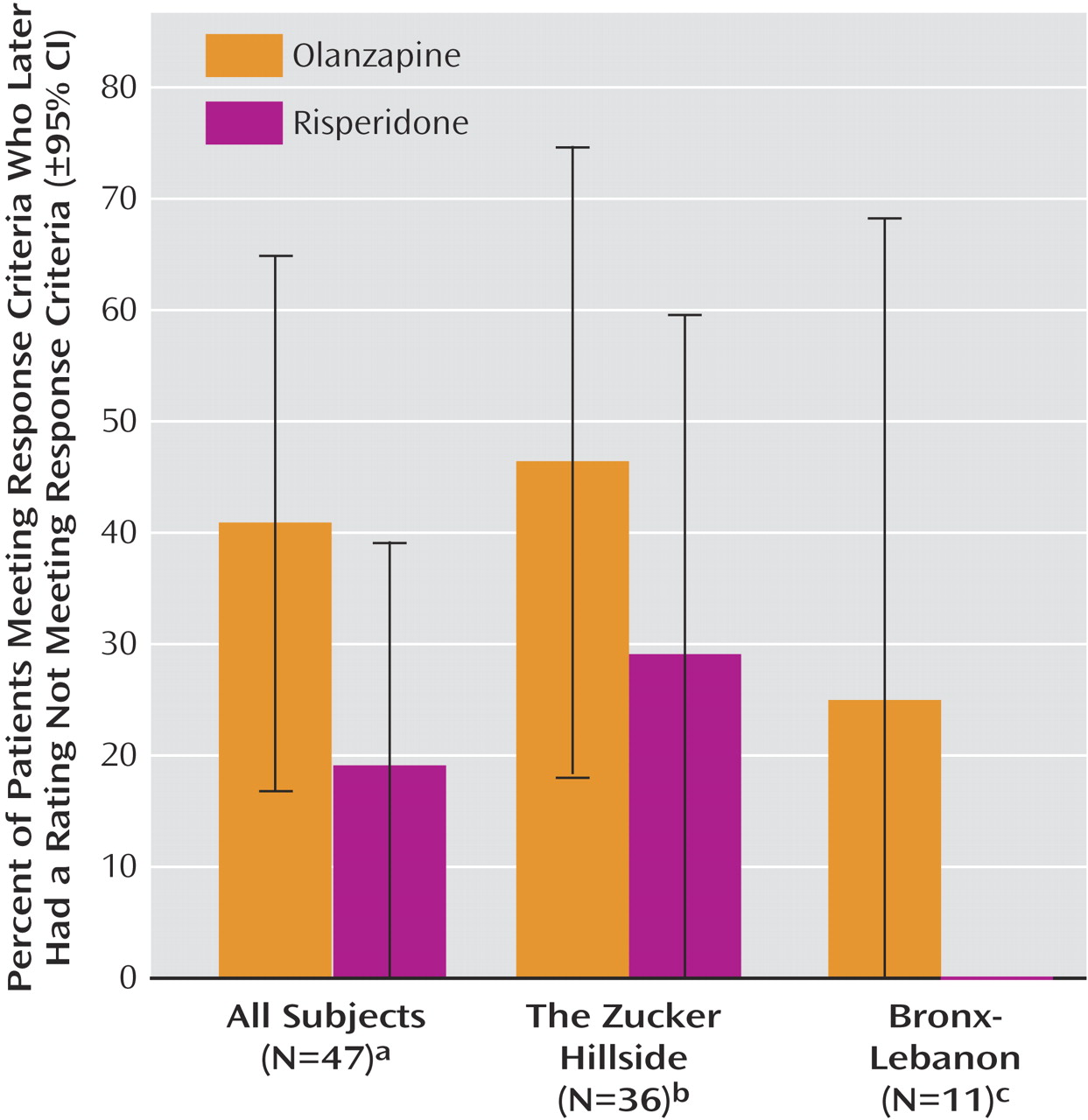

As shown in

Figure 3, approximately twice as many subjects who responded to olanzapine (40.9%, 95% CI=16.8%–65.0%) compared with risperidone (18.9%, 95% CI=0%–39.2%) later had ratings no longer meeting substantial improvement criteria, but the difference fell short of statistical significance (log-rank test, χ

2 =3.02, p<0.08). The mean length of time that subjects maintained their responder status was 6.6 weeks (95% CI=5.6–7.7) with olanzapine and 9.5 weeks (95% CI=8.6–10.4) with risperidone.

There were no significant differences between medications and no medication-by-time interactions in analyses of the delusions, hallucinations, and thought disorder measures. Delusions (F=19.92, df=11, 853, p<0.0001), hallucinations (F=23.53, df=11, 853, p<0.0001), and thought disorder (F=14.02, df=11, 853, p<0.0001) improved over time. Thought disorder severity differed across sites (F=7.28, df=1, 109, p<0.01), with higher ratings seen among subjects at The Zucker Hillside (5.0, 95% CI=4.5–5.4) than among those at Bronx-Lebanon (3.9, 95% CI=3.3–4.6).

There were no significant differences between medications and no medication-by-time interactions in analyses with the SANS global measures for affective flattening, alogia, avolition-apathy, and asociality-anhedonia. Only avolition-apathy (F=2.43, df=11, 816, p<0.01) and asociality-anhedonia (F=5.29, df=11, 816, p<0.0001) improved significantly over time. The estimate of adjusted mean for avolition-apathy at baseline was 2.9 (95% CI=2.7–3.1); the lowest value across time was 2.4 (95% CI=2.4–2.9) at week 6. For asociality-anhedonia, the corresponding results were 3.0 (95% CI=2.8–3.3) at baseline and 2.4 (95% CI=2.2–2.6) at week 4. Subjects at The Zucker Hillside were rated higher than those at Bronx-Lebanon on affective flattening (2.2 [95% CI=2.1–2.4] versus 1.7 [95% CI=1.4–2.0]; F=11.10, df=1, 109, p<0.01), alogia (1.9 [95% CI=1.8–2.1] versus 1.4 [95% CI=1.2–1.7]; F=10.29, df=1, 109, p<0.01), and asociality-anhedonia (2.8 [95% CI=2.6–2.9] versus 2.4 [95% CI=2.1–2.6]; F=6.50, df=1, 109, p<0.01).

Side Effects

The cumulative rate of parkinsonism did not differ significantly between medications; the rate was 8.9% (95% CI=0.3%–17.6%) with olanzapine and 16.0% (95% CI=5.5%–26.6%) with risperidone. Significant effects of time (F=2.33, df=11, 877, p<0.01) and site (F=4.25, df=1, 109, p<0.04) were revealed in analysis of the extrapyramidal symptom severity score data, but there was no time-by-treatment interaction. Simpson-Angus Rating Scale scores were slightly higher for Bronx-Lebanon subjects (1.4; 95% CI=1.2–1.7) than for The Zucker Hillside subjects (1.1; 95% CI=1.0–1.3). The extrapyramidal symptom score of risperidone-treated subjects (1.4, 95% CI=1.2–1.6) was slightly higher than that of olanzapine-treated subjects (1.2, 95% CI=1.0–1.4), but the difference fell short of statistical significance (F=3.42, df=1, 109, p<0.07). The repeated-measures ANOVA of the Barnes global akathisia item revealed a significant site difference (F=5.64, df=1, 109, p<0.02) but no effects of medication assignment or time. Subjects at Bronx-Lebanon had slightly more akathisia (0.4, 95% CI=0.3–0.5) than subjects at The Zucker Hillside (0.3, 95% CI=0.2–0.3). More subjects taking risperidone than olanzapine were prescribed benztropine for extrapyramidal symptoms, but the difference was not significant (χ 2 =3.8, df=1, p<0.06). Prescription of propranolol for akathisia followed the same pattern (χ 2 =2.9, df=1, p<0.09).

The mean weight at study entry for all subjects was 70.1 kg (SD=16.6). The primary weight analyses based upon the entire 4-month period revealed an increase of weight over time (F=16.63, df=15, 469, p<0.001) and more weight gain with olanzapine compared with risperidone (F=8.01, df=1, 88, p<0.01). No medication-by-time interaction or site differences were found. Results of the analyses of the BMI data were the same as the analyses using weight as the dependent measure. The percent weight gain from baseline to 4 months was 17.3% (95% CI=14.2%–20.5%) with olanzapine and 11.3% (95% CI=8.4%–14.3%) with risperidone. The estimate of adjusted mean of BMI increased from 24.3 (95% CI=22.8–25.7) at baseline to 28.2 (95% CI=26.7–29.7) at 4 months with olanzapine and from 23.9 (95% CI=22.5–25.3) to 26.7 (95% CI=25.2–28.2) with risperidone.

Our secondary weight analyses revealed a significant increase of weight with time (F=16.66, df=15, 467, p<0.0001) and an antipsychotic-by-divalproex interaction (F=11.28, df=1, 9, p<0.01) but no significant effects of site, substance use, sertraline use, or the interactions of antipsychotic medication by time or sertraline by antipsychotic medication. The weight gain associated with combined olanzapine and divalproex treatment was more than with olanzapine alone (t=2.96, df=9, p<0.02), risperidone alone (t=3.90, df=9, p<0.01), or risperidone combined with divalproex (t=4.43, df=9, p<0.01). Treatment with olanzapine alone was associated with more weight gain than with risperidone alone (t=2.51, df=9, p<0.03) or risperidone plus divalproex (t=3.28, df=9, p<0.01). Weight gain with risperidone alone and risperidone plus divalproex did not differ significantly (t=1.90, df=9, p<0.09). Percent gains from baseline weight at 4 months for each medication condition were as follows: olanzapine plus divalproex, 25.1% (95% CI=19.3%–31.3%); olanzapine alone, 15.9% (95% CI=12.7%–19.1%); risperidone alone, 11.2% (95% CI=8.1%–14.5%); risperidone plus divalproex, 10.9% (95% CI=6.2%–15.8%).