Although it has long been known that attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) often persists into adulthood

(1,

2), adult ADHD has only recently become the focus of widespread clinical attention

(3 –

5) . As an indication of this neglect, adult ADHD was not included in either major U.S. psychiatric epidemiological survey of the past two decades, the Epidemiologic Catchment Area Study

(6) or the National Comorbidity Survey

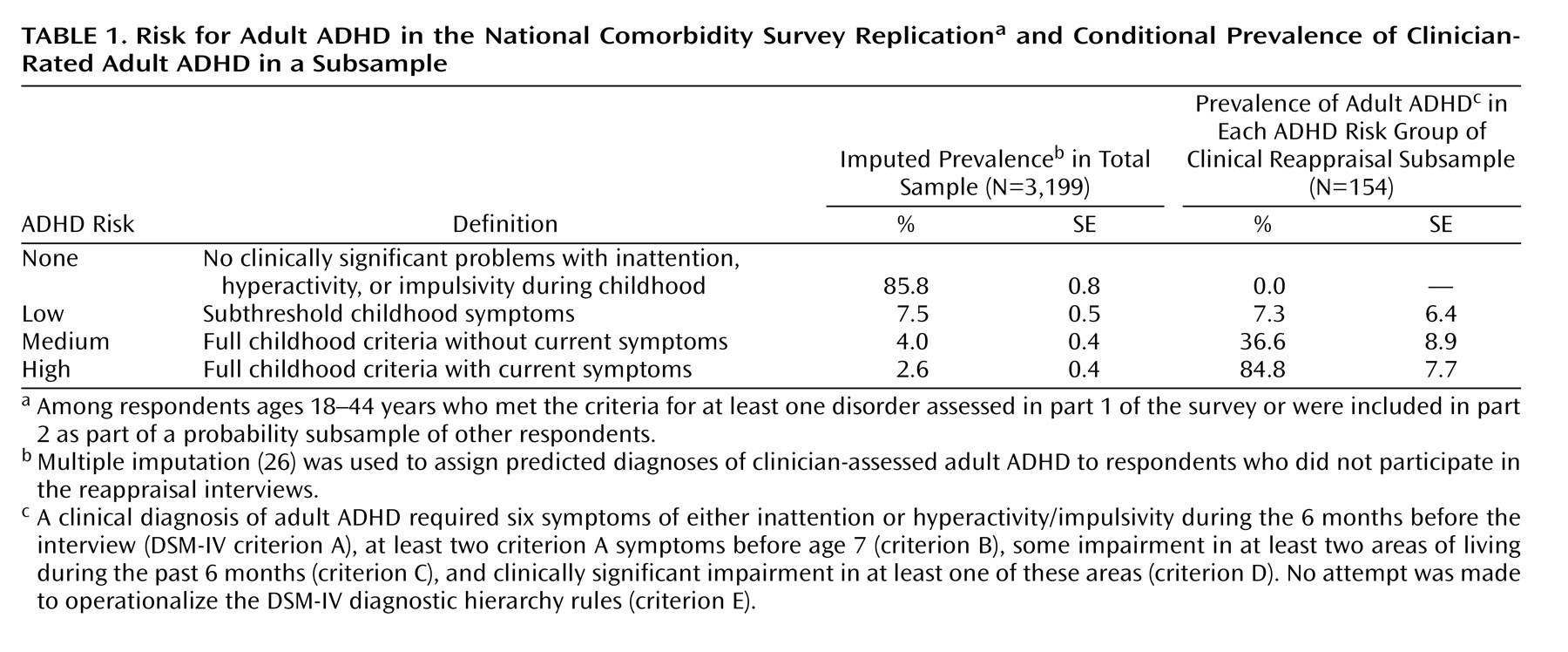

(7) . Attempts to estimate the prevalence of adult ADHD by extrapolating from childhood prevalence estimates linked with estimates of adulthood persistence

(8 –

11) and direct estimation in small subject groups

(12,

13) have yielded estimates in the range of 1%–6%. In order to obtain more accurate estimates of prevalence and correlates, an adult ADHD screen was included in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication

(14), and clinical reappraisal interviews were carried out with people who had positive results on the screen. These data are used here to estimate the prevalence, comorbidity, and impairment of adult ADHD in the United States.

Discussion

An important limitation is that the DSM-IV criteria for ADHD were developed with children in mind and offer only minimal guidance regarding diagnosis among adults. Clinical studies make it clear that symptoms of ADHD are more heterogeneous and subtle in adults than children

(32,

33), leading some clinical researchers to suggest that assessment of adult ADHD requires an increase in the variety of symptoms assessed

(34), a reduction in the severity threshold

(35), or a reduction in the DSM-IV requirement for six of nine symptoms

(36) . To the extent that such changes would lead to a more valid assessment than in the current study, our prevalence estimate is conservative.

Three additional limitations are also noteworthy. First, adult ADHD was assessed comprehensively only in the clinical reappraisal subsample. Although the imputation equation was strong, the need to impute entire diagnoses made it impossible to carry out symptom-level investigations of possibilities such as greater prominence of inattentive symptoms, relative to hyperactive/impulsive symptoms, among adults than among children.

Second, both the CIDI and clinical reappraisal interviews were based on self-reports. Childhood ADHD is diagnosed on the basis of parent and teacher reports

(37) . Informant assessment is much more difficult for adults, making it necessary to base assessment largely on self-report

(38) . Methodological studies comparing adult self-reports and informant reports of ADHD symptoms have documented the same general pattern of underestimation in self-reports by adults as in those by children

(39,

40), suggesting that our prevalence estimates are probably conservative, although the only study we know of that compared self and informant assessments of adult ADHD in nonclinical subjects showed fairly strong associations between the two reports

(41) .

Third, even though the semistructured interview used in the clinical reappraisal interviews, the Adult ADHD Clinical Diagnostic Scale, had been used in clinical studies of adult ADHD, there is no standard method for clinical validation of adult ADHD with the same level of acceptance as the SCID has for anxiety, mood, or substance use disorders, limiting the interpretability of results.

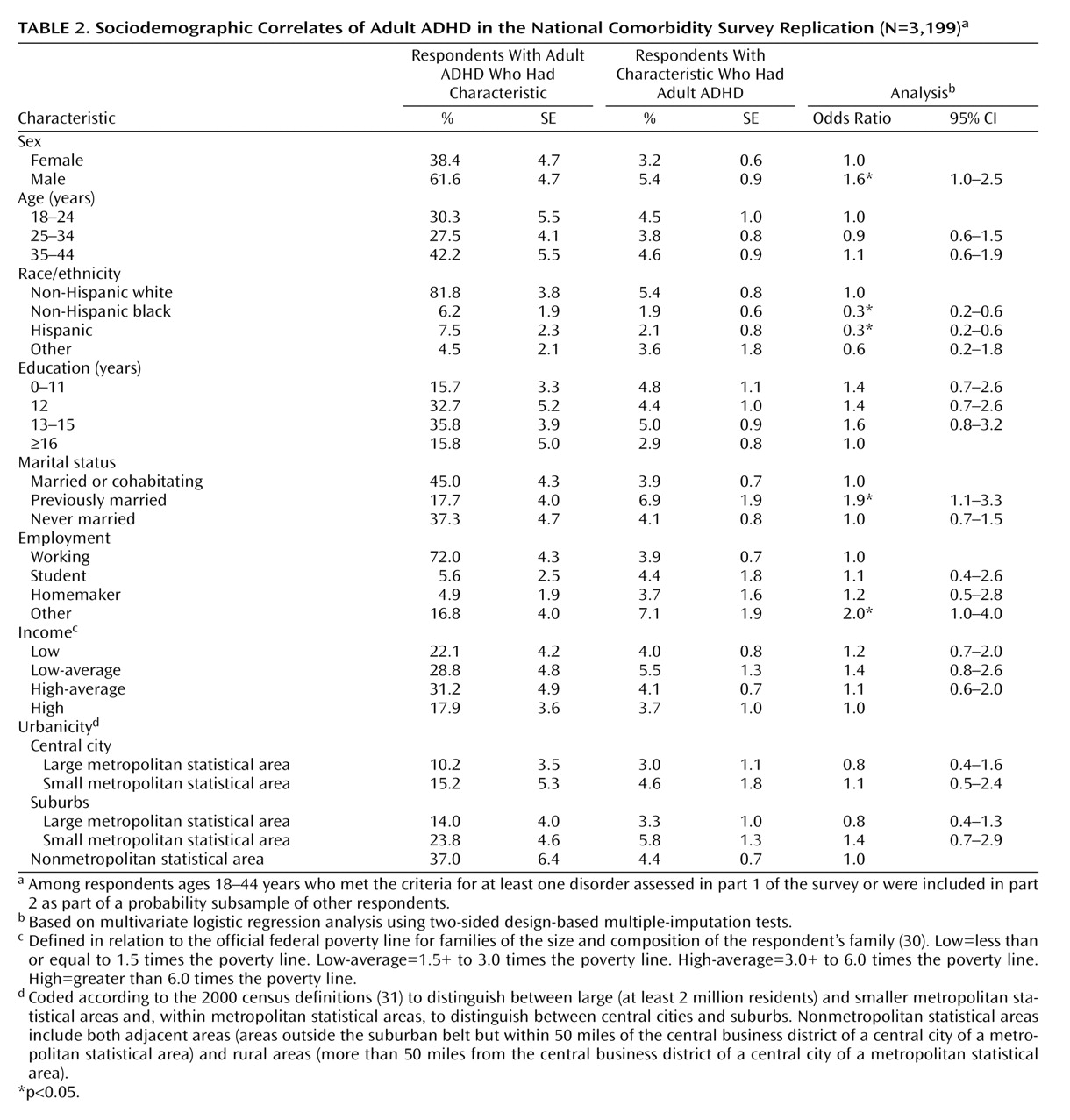

Within the context of these limitations, the results reported document that adult ADHD is common and often produces serious impairment. The 4.4% estimated prevalence is in the middle of previous estimates. This estimate is likely to be conservative for the reasons we have just described. The findings that adult ADHD is associated with unemployment and with being previously married are broadly consistent with results from studies that have documented adverse effects of adult ADHD

(8,

42) . The analyses of responses to the WHO Disability Assessment Schedule are also consistent with this broad pattern. However, the disability results might underrepresent ADHD impairments because some dimensions of the scale tap areas in which ADHD does not produce great impairment (e.g., people with ADHD are often very mobile and overwork) and because the scale does not assess many dimensions in which people with ADHD are thought to function least adequately (e.g., poor sleep and nutrition, accidents, and smoking are common). In addition, as already noted, people with ADHD might have poor insight into their impairments, leading to underestimation of scores on the WHO Disability Assessment Schedule.

The finding of low prevalences among Hispanics and non-Hispanic blacks was unexpected. As the DSM-IV ADHD field trials indicated no effects of race/ethnicity

(43), these findings in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication could reflect a race/ethnic difference in adult persistence, in accuracy of adult self-report, in cultural perceptions of the acceptability of ADHD symptoms, or some combination. The finding that adult ADHD is significantly more prevalent among men than women, in comparison, is consistent with much previous research

(44) . The 1.6 male-female odds ratio is comparable to the odds ratios found in studies of children and adolescents, suggesting that childhood or adolescent ADHD is no more likely to persist into adulthood among girls than boys

(45) . This indirectly suggests that the high proportion of women in adult ADHD patient groups is due to help seeking or recognition bias

(46) . The finding that adult ADHD is highly comorbid is consistent with clinical evidence

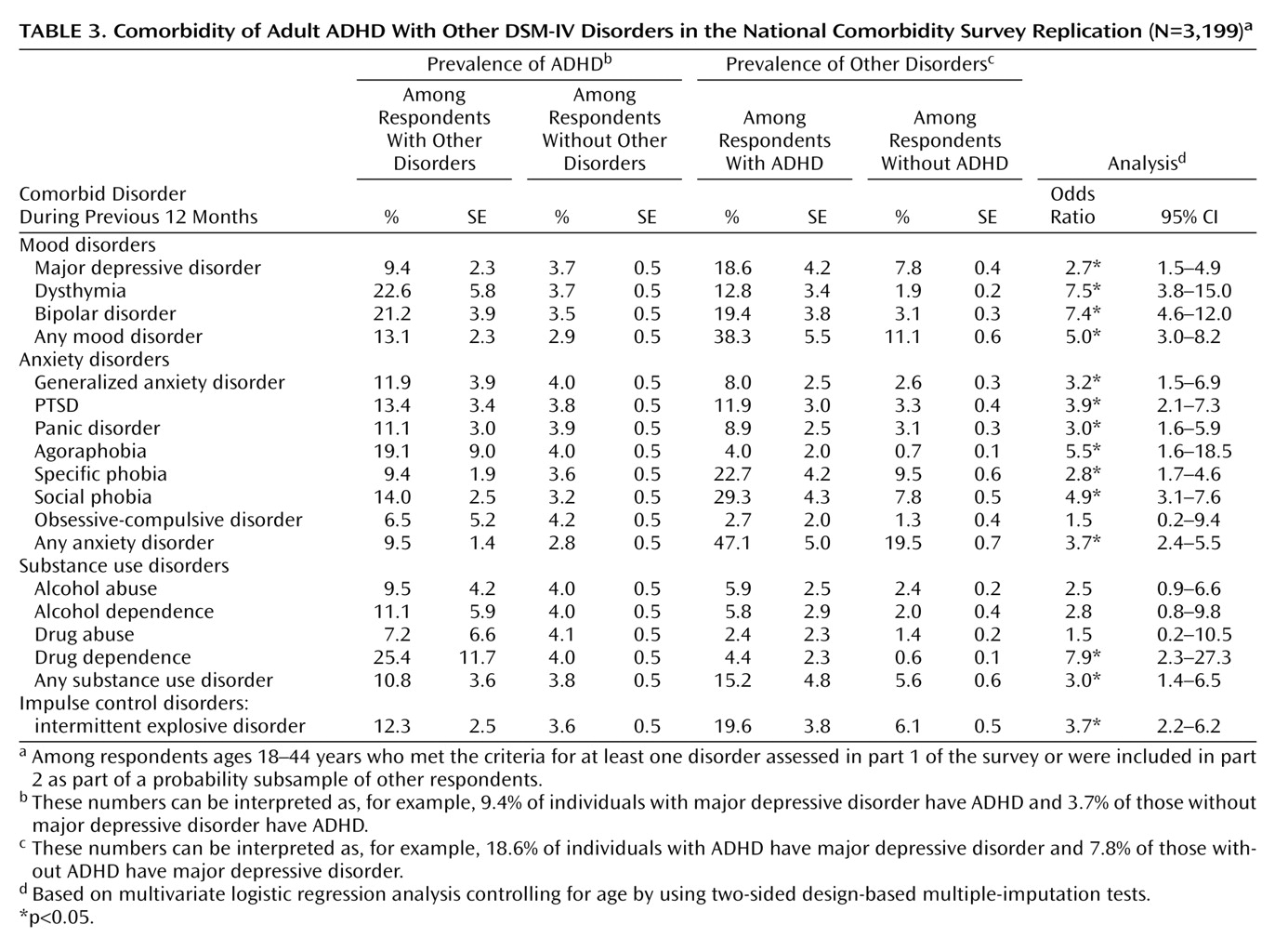

(42) . Methodological analysis has shown that these comorbidities are not due to overlap of symptoms, imprecision of diagnostic criteria, or other methodological confounds

(47) .

The average magnitude of the odds ratios reflecting the relationship between adult ADHD and other comorbid disorders is comparable to those for most of the DSM-IV anxiety and mood disorders assessed in the survey

(48) . The absence of strong variation in comorbidity odds ratios was surprising, as family studies would lead us to predict high comorbidities with major depression

(49), bipolar disorder

(50,

51), and conduct disorder

(52,

53) and lower comorbidity with anxiety disorders

(54) . One striking implication of the high overall comorbidity is that many people with adult ADHD are in treatment for other mental or substance use disorders but not for ADHD. The 10% of respondents diagnosed with ADHD who had received treatment for adult ADHD is much lower than the rates for anxiety, mood, or substance use disorders

(55) . Direct-to-consumer outreach and physician education are needed to address this problem.

The comorbidity findings raise the question of whether early successful treatment of childhood ADHD would influence secondary adult disorders. The fact that a diagnosis of adult ADHD requires at least some symptoms to begin before age 7 means that the vast majority of comorbid conditions are temporally secondary to adult ADHD. We know from the Multimodal Treatment Study of ADHD that successful treatment of childhood ADHD also reduces childhood symptoms of comorbid disorders

(56) . Indirect evidence suggests that stimulant treatment of childhood ADHD might reduce subsequent risk of substance use disorders

(57), although this is not definitive because of possible sample selection bias. Long-term prospective research using quasi-experimental methods is needed to resolve this uncertainty.

A related question is whether adult treatment of ADHD would have any effects on the severity or persistence of comorbid disorders. A question could also be raised as to whether ADHD explains part of the adverse effects found in studies of comorbid DSM disorders. A number of studies, for example, have documented high societal costs of anxiety disorders

(58,

59), mood disorders

(60,

61), and substance use disorders

(62,

63), but these all ignored the role of comorbid ADHD. Reanalysis might find that comorbid ADHD accounts for part, possibly a substantial part, of the effects previously attributed to these other disorders.

Acknowledgments

Collaborating investigators in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication include Ronald C. Kessler (principal investigator, Harvard Medical School), Kathleen Merikangas (co-principal investigator, NIMH), James Anthony (Michigan State University), William Eaton (The Johns Hopkins University), Meyer Glantz (National Institute on Drug Abuse), Doreen Koretz (Harvard University), Jane McLeod (Indiana University), Mark Olfson (Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons), Harold Pincus (University of Pittsburgh), Greg Simon (Group Health Cooperative), Michael Von Korff (Group Health Cooperative), Philip Wang (Harvard Medical School), Kenneth Wells (UCLA), Elaine Wethington (Cornell University), and Hans-Ulrich Wittchen (Max Planck Institute of Psychiatry).