Few in psychiatry would dispute the validity of this absolute stance on rigorous boundary-keeping in long-term psychotherapy. Nevertheless, thoughtful, ethically committed professionals have raised important questions about the scope of this professional guideline in other aspects of academic medicine

(4,

5) . For instance, as modern psychiatry has evolved to encompass diverse roles and activities, it is unclear whether it is psychotherapy, psychiatric treatment, or perhaps, more broadly, medical care that generates such a firm standard for conduct. Is it

always and under

all circumstances exploitative for

any psychiatrist to accept a gift from a patient? Is this true for all patients, irrespective of type of illness and nature of treatment? How about a gift from someone else’s patient? How about gifts for psychiatrists functioning in nonclinical roles (e.g., administrative)? Are the boundaries the same for patients from a small community or a distinct cultural group where gift-giving may have different meaning

(6) ? How about a small gift? How about a larger gift from a person with substantial financial resources? Can a gift ever truly be given voluntarily and without the expectation of reciprocity? If, in theory, a gift may be ethical, what constraints are there? What kind of gift is sufficient to cause a conflict of interest that will undermine the position of respectful, beneficent, and concerned “neutrality” that psychiatrists must maintain in their professional activities

(7,

8) ?

Philanthropic giving in academic psychiatry similarly raises many questions

(5), leading many medical school development offices to treat departments of psychiatry as inappropriate targets for fundraising

(4) . Yet, on an intuitive level, these questions do not find easy resolution in the absolute standard derived from the long-term psychotherapy ethical model. Certainly psychiatrists cannot under any circumstances approach their own patients for donations. But what other “rules” exist? It does not seem reasonable, for example, that a medical school dean should decline an unsolicited contribution from a colleague’s “grateful patient” who wishes to support a new program initiative or an endowed chair simply because the donor has a mental illness. But what if the dean is also a psychiatrist? Is a psychiatrist-dean held to a different standard than a pediatrician-dean, internist-dean, or surgeon-dean? And, if the psychiatrist-dean can accept unsolicited donations from patients to the institution, can a psychiatry chair accept unsolicited donations from patients cared for in his or her department? Separate from the psychiatrist’s leadership role, are some mental illnesses “permissible” while others are not? Taken further, what is the rationale for curtailing the opportunities of a person with, say, a time-limited and nonsevere mental illness as opposed to, say, a catastrophic physical illness where philanthropic donations are commonly seen as acceptable? To what extent are prejudicial attitudes and stigma coloring these views and practices? Is this about ethics

per se, or is it part of a larger societal pattern of neglect, disrespect, and inequity around mental illness issues?

Taken together, these questions call for a more nuanced understanding of gift-giving in academic psychiatry. It is clear that overly simplistic, “hard-and-fast” rules do not offer sufficient guidance to medical schools and related organizations that seek to act ethically in their efforts to support the development of mental illness-related programs. The aims of this article are thus to characterize specific ethical considerations in psychiatry and philanthropy and to outline and illustrate steps that may be taken by academic institutions to set the stage for ethical fundraising in psychiatry.

Ethical Considerations in Psychiatry and Philanthropy

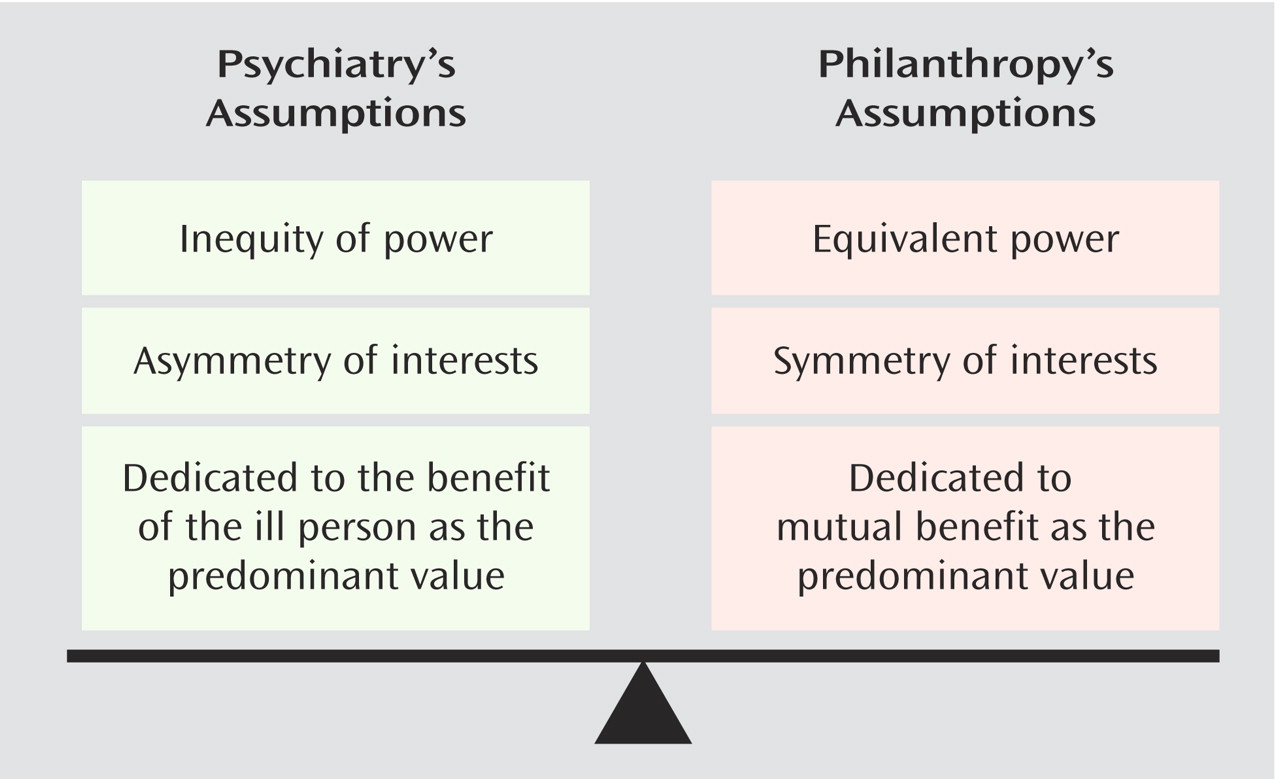

Ethical guidelines in psychiatry and philanthropy are in tension (

Figure 1 ). Psychiatry’s ethics principles typically relate to assumptions about the inherent inequalities in the physician-patient relationship. People with mental illness experience symptoms that find expression in cognition, personality, and behavior, affecting an individual’s ideas, motivations, and capacity to engage in everyday roles and relationships. Mental illness affects one in five people over their lifetimes, and it causes a unique form of suffering that is often amplified by economic and health care disadvantages and by stigma in our society

(9,

10) . When people with mental illness seek psychiatric help, they often have been ill for a very long time or are very seriously ill. They place themselves in the hands of psychiatrists with the expectation that the psychiatrists’ specialized expertise and therapeutic efforts will be dedicated

solely to alleviating their suffering. This dedication to the interests and well-being of people with mental illness is the core of professionalism in psychiatry. Guidelines for ethical psychiatric practitioners thus focus principally on applying clinical knowledge and judgment, bringing genuine benefit, avoiding harm, setting aside self-interest, and using their influence in a respectful, correct, and restrained manner in their interactions with patients

(1,

7) .

Philanthropy’s ethics principles, on the other hand, relate to assumptions about the mutualism and symmetry of interests in the benefactor-recipient relationship

(11) . In philanthropy, both parties are viewed as robust—a donor with resources to provide, and an institution with the capacity to make that gift translate into something of importance and value. The benefactor receives certain advantages, from actuarial to altruistic, and the institution receives resources to advance its mission and impact. Philanthropic gifts thus have an inherent reciprocity. More than simply raising dollars, or more positively, more than simply facilitating acts of charity, philanthropy is a profession. Its objective in academic medicine is to foster a respectful, beneficial cooperative relationship for the purpose of attaining a salient, specific, and shared goal. Ethical guidelines in philanthropy primarily relate to honesty, clarity in communication of goals, explicit definition of products or outcomes to be “delivered” because of the gift as well as timelines, fidelity to what has been committed, and careful oversight of resources

(11) .

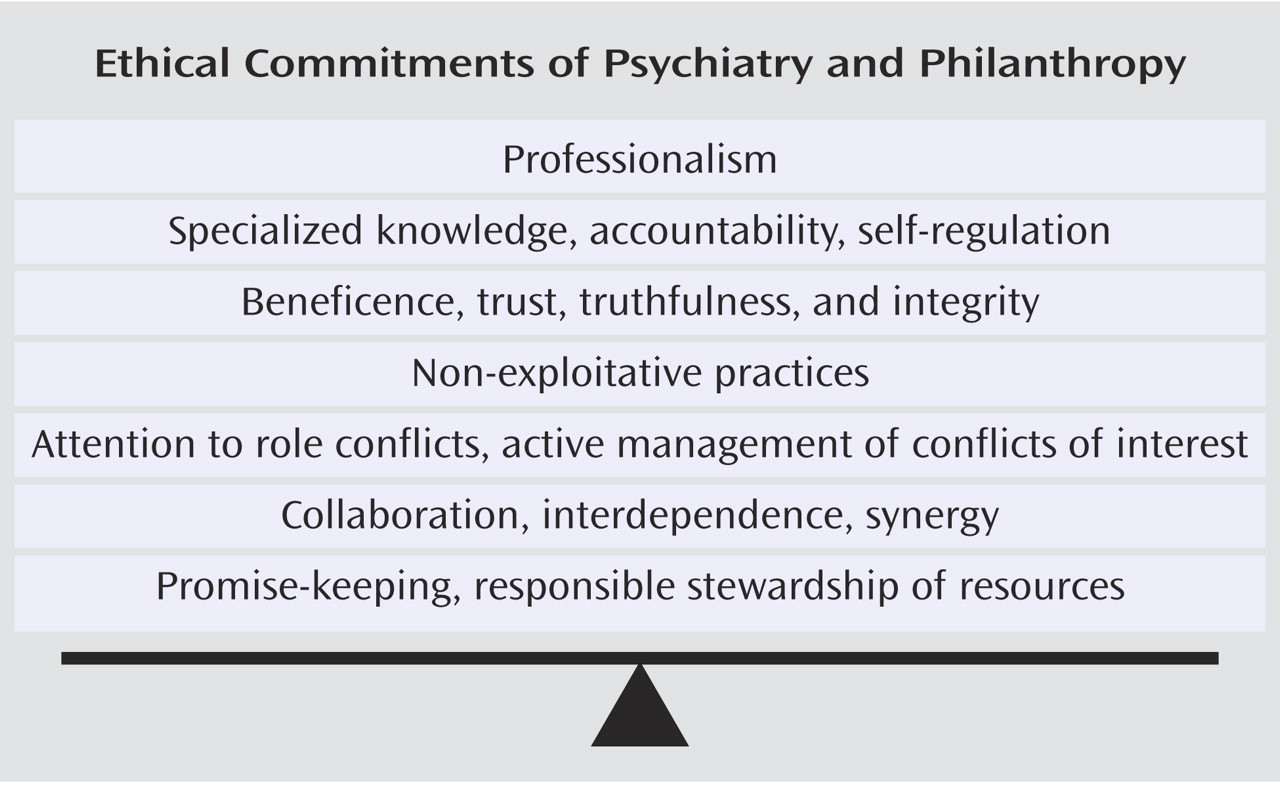

Despite these apparent differences in orientation, psychiatry and philanthropy do have common ground in terms of their ethical commitments (

Figure 2 ). They are both professions, and as such involve specialized knowledge, highest levels of accountability, and the expectation of self-regulation

(1,

5,

11,

12) . Both psychiatry and philanthropy are committed to trust, truthfulness, and integrity in all of their dealings with others. Both professions seek to do good through their unique activities in society. Both professions aspire to nonexploitative practices, and both are attentive to role conflicts and the active management of conflicts of interest. Psychiatry and philanthropy emphasize collaboration, entail interdependence, and affirm the benefit derived from combining strengths. Finally, they are both committed to promise-keeping and responsible stewardship of resources. These shared features of the two professions permit the development of a new approach to ethical philanthropy in academic psychiatry.

Steps Toward Ethical Philanthropy in Academic Psychiatry

The key to ethical philanthropy in academic psychiatry is undertaking a series of steps that will create a structured, explicit, safeguarded approach within each institution for fundraising and gift-giving in the context of mental illness. A committed advisory workgroup that fosters greater understanding, receptiveness, and critical self-observation in the institutional environment is essential in this process. The advisory workgroup and safeguards, in concert, will help assure that conflicts of interest do not threaten the integrity of the decision-making that is made in relation to philanthropic activities for psychiatry.

Establishing an Advisory Workgroup

An initial step is to assemble a small advisory workgroup to clarify core issues and offer guidance to the institution, given its specific structure, culture, and context. Ideally, the workgroup will be populated by individuals who can represent relevant perspectives and are knowledgeable about medical school, affiliate, and community issues. The workgroup thus may include professionals and lay people, such as a development officer, a psychiatric clinician, an administrator or administrative leader in psychiatry, an established medical school benefactor, liaison members from affiliates, an ethicist with appropriate expertise or experience and, importantly, a consumer of mental health services or a family member.

The moral tenor and tasks of workgroup discussions will merit close attention as will its composition. Genuine collaboration and principled but flexible thinking will be required of the group. Ideally, the dialogue will be kept “down to earth” and not used as a “soapbox” for airing certain concerns or grievances. The purpose of the workgroup is to generate a constructive “working understanding” of the complex issues inherent to philanthropy and psychiatry before turning to the task of creating formal routines or policies. This working understanding will be held by a set of committed, knowledgeable, and representative “stakeholders” who are attentive to the unique issues that exist within the specific organization and its affiliates. Consequently, individuals who cannot think beyond certain political or personal agendas will not be good committee members. Further, it may be necessary to restrict the scope of issues undertaken by the committee. For example, it would be best to separate discussion of philanthropic activities involving patients, families, and nonprofit organizations from other fundraising activities involving for-profit and commercial groups (e.g., pharmaceutical companies).

The chair of the committee, moreover, has a crucial role. He or she must be capable of communicating the importance of the issues as well as the shared ethical commitments of psychiatry and philanthropy. The chair will need to create a milieu of openness and trust in the discussions and will need to address confidentiality concerns that arise. At the same time, the chair will need to explicitly address potentially awkward conflicting roles and conflicts of interest of workgroup members. In addition, it will be important to reassure the patient and family member that their perspectives are valued and that the medical school is not seeking their participation in order to obtain a donation to the school. The chair of the group will thus need to be skilled at managing group discussions and absolutely must understand the value of mental health care but probably should not be a psychiatrist because of vulnerability to the criticism of being, or appearing to be, “self-serving.” Through such efforts, it will help assure that the workgroup has credibility in the face of skeptics who will worry that the process merely is a rubber stamp for financial opportunism.

It is also vital that the workgroup understands the reasons for its inherent “advisory” function or scope of responsibility within the larger organization of the medical school. Because of the legal, financial, and administrative aspects of the issues under consideration, the workgroup cannot be fully independent or separately accountable from other aspects of departmental and school administration. Depending on the circumstances, the advisory workgroup may be maintained as a standing committee (e.g., if a lot of fundraising pertaining to psychiatry is expected), may be “sundowned” (e.g., if institutional offices can appropriately manage whatever issues arise), or reactivated on an “as-needed” basis (e.g., if a major donation is anticipated and the workgroup can help with safeguarding the process). To whatever extent possible, the workgroup should be included in selecting which of these paths is taken.

Initial Tasks

The workgroup should first consider issues that will help define the boundaries around acceptable philanthropic practices within the institution. An early task will be to clarify whether there are approaches that should be prospectively defined as

not permissible in relation to psychiatry. Ethics writings

(13,

14) and national ethical guidelines will help clarify some of these issues. For instance, it would not be considered acceptable for a caregiving psychiatrist to directly solicit a donation from an individual patient

(1 –

3,

5) . Fidelity to the patient’s well-being and committed attention to the therapeutic responsibilities of the psychiatrist-patient relationship are imperative; these duties take precedence over all other interests. Careful clarification of the goals of the donation is also essential in identifying and, later, resolving ethically important issues. Consider the situation of a financial contribution that is fundamentally driven by a personal therapeutic concern (e.g., seeking access or approval from a personal caregiver), rather than an authentic and separate philanthropic objective. If a patient for whom an institution has therapeutic responsibility would or could be hurt in any way by a philanthropy-related interaction, then the donation should be declined. These kinds of gift-giving situations should be identified as “off limits.” In addition, explicit efforts to help deal with the disappointment, frustration, or other difficult psychological issues that may arise when declining a donation should be considered in these discussions.

The workgroup may wish to consider “usual” practices for fundraising involving grateful patients in other parts of the institution for their suitability, or unsuitability, in psychiatry. To illustrate, some institutions may use lists of potential donors with some reference to the illness or “cause” that they are most concerned about. When mental illness is involved, this “tie” to a clinical diagnosis may be stigmatizing. Workgroup members will need to consider whether practices such as these should be used in relation to fundraising for psychiatry-related initiatives at their medical school.

Second, the workgroup should identify philanthropic activities related to mental illness and psychiatry that do not appear to be ethically problematic. One example would be to make sure that the general fundraising materials of the institution include psychiatric programs, or patients with mental illness, as an “earmarked” destination for donations—a common practice for pediatric programs or patients with cancer. The workgroup could also explore program development opportunities related to mental illness that have merit in light of other initiatives at the institution. Examples may include creating a behavioral health component in a cardiac care center, an autism unit in an affiliated pediatric hospital, or a psycho-oncology initiative in a breast cancer program. The philanthropic targets may be linked with pressing local and national issues, such as proactive efforts to prevent teen suicide, to perform research in elder mental health, or to build better access for certain underserved patient populations. Fundraising goals may also be defined in relation to salient events within the area, such as the effects of fire or flood on neighboring families, the mental health consequences of a local factory closure, or impact of the death of a prominent community leader to suicide.

Several ethics concepts will have central importance in the workgroup’s discussions of unacceptable and acceptable practices for psychiatric fundraising at the institution. The duty to place therapeutic obligations above all other interests ( beneficence ) and to adhere to this principle rigorously ( integrity ) will have greatest weight in these deliberations. In addition, the workgroup will need to consider institutional practices in light of other ethically important issues such as respect for the rights and autonomy of people with mental illness and the heightened expectations for confidentiality . Finally, the workgroup will need to think about promise-keeping ( fidelity ) and responsible use of resources ( stewardship ). Each of these concepts is important, but beneficence and integrity are the ‘first among equals’; they are the principles with the greatest weight in establishing practices—and precedents—within the institution. This collaborative dialogue will help the advisory workgroup develop a shared working understanding of how to assign proper valence to specific ethical concerns that will arise in relation to gift-giving at the institution. These are situations riddled with competing pressures and conflicting interests but which may be resolved through explicit ethical decision-making and safeguarding efforts.

Ethical Decision-Making and Safeguards in Philanthropy

The next step is setting up an explicit framework for ethical decision-making as well as safeguards for fundraising methods related to mental illness-related initiatives within the institution. When a “grateful patient” with mental illness is involved, the decision-making model involves systematically considering the reasons for the potential donation as well as the goals and expectations attached to the contribution. The ethical consideration of greatest importance in deciding whether to accept a donation is patient well-being; if it appears that a personal therapeutic concern (e.g., unusual beliefs, desire to please the caregiving psychiatrist, seeking access to personal health care) is driving the situation, then the donation should be declined under all but the most extraordinary circumstances. If the donor is a family member rather than a patient, then the institutional and individual professional obligation to help assure well-being are lessened but perhaps not entirely eliminated. Key ethical considerations for all donors include fulfilling the other ethical commitments shared across psychiatry and philanthropy (such as truthfulness and promise-keeping) and responsible stewardship of resources. Does the donor understand, for example, how endowments work and have a realistic understanding of what can be accomplished with the funds provided? Does the institution have any reason to believe that the donor is not well-positioned (e.g., financially, emotionally, clinically) to make a voluntary gift to the institution to accomplish a mutual goal? Has the institution been clear and responsible in defining what the “deliverable products” are, and has this information been communicated and well-understood in discussions with the donor?

This explicit decision-making process produces an interpretation of ethical “risk.” Sometimes the ethical problems are immediately evident. One example would be the serious ethical problems that would preclude accepting the donation of a patient with bipolar disease who, while in the manic phase of his serious illness, makes a $20,000 contribution to the medical school along with purchasing a new car and running up a large gambling debt. At other times, however, the problems may be more difficult to discern because they may relate to subtler motives, hopes, interpersonal interactions, and overlapping and conflicting roles in a local context. Exploring the specific issues that come up in realistic hypothetical cases or actual situations from the institution’s past experience may be especially helpful in this discussion. This analysis will give an indication of whether a gift should, from an ethical perspective, be pursued, delayed, or stopped altogether and what level of safeguards may be necessary for gift-giving to proceed appropriately.

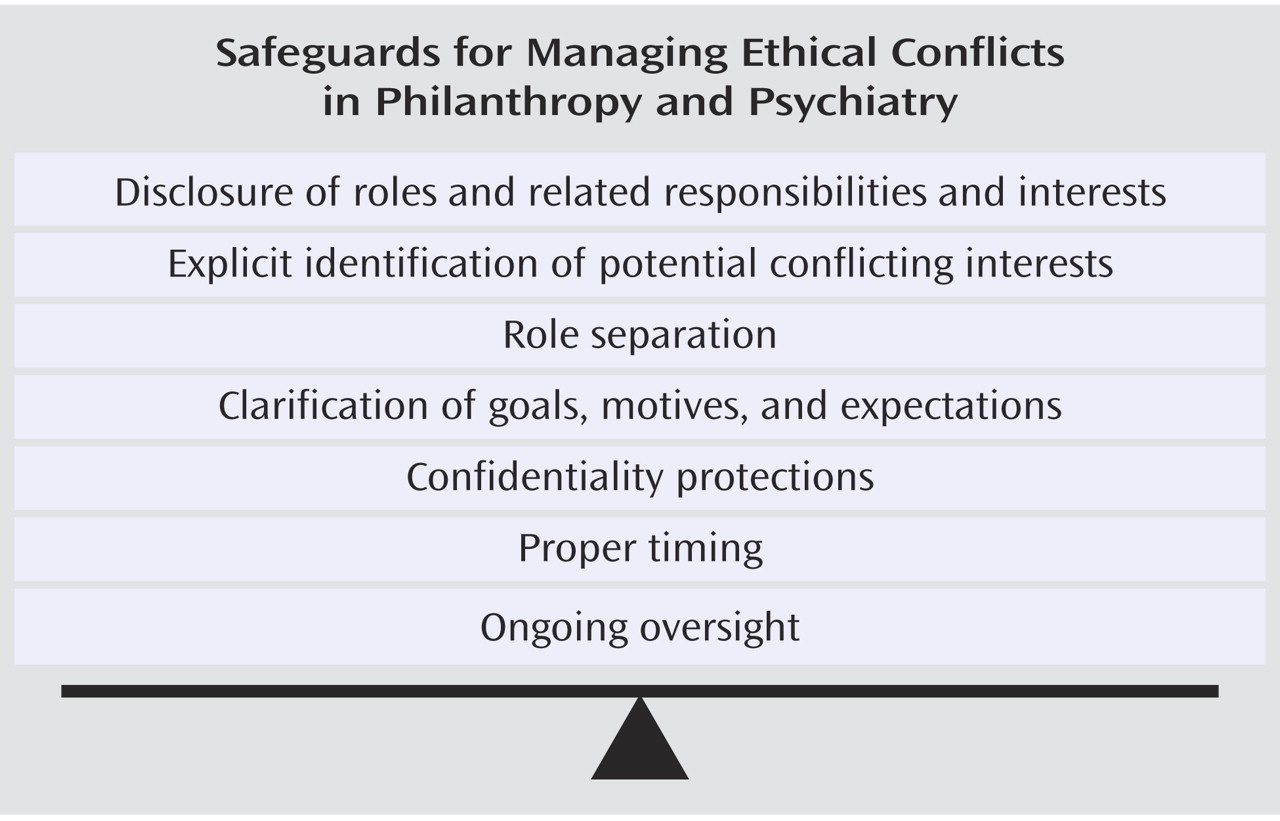

There are multiple safeguards for managing ethical conflicts in philanthropy and psychiatry (

Figure 3 ), as there are with conflict of interest-type situations.

Disclosure of various roles and the obligations and explicit

identification of

potential conflicting interests that derive from these roles are the most important methods in current practice.

Role separation is also vital, particularly if there is any overlap with an ongoing or recent therapeutic relationship with a psychiatrist at the institution. In philanthropic situations, it is also important to engage in a verbal, and often written, process to

clarify goals,

motives, and

expectations associated with a donation to assure that they are realistic, congruent with what is possible within a particular setting, and authentic. This safeguard is especially important to support good communication and to prevent misunderstanding or erroneous assumptions that lead to donation decisions.

Confidentiality protections are critically important in philanthropy in psychiatry. Care in maintaining donor databases is essential, for example. And rather than using patient contact information for institutional fundraising, developing lists of potential benefactors by working with partner organizations (e.g., mental health advocacy groups) or information available in the public domain (e.g., newspaper articles) is a valuable approach. Attention to proper timing is another measure that may have a role in safeguarding against exploitation. A decision to make a donation during a time of stress, severe symptoms, or emotional fragility is more vulnerable ethically than a settled, sustained decision from a sturdy benefactor. Finally, ongoing oversight by a small group of impartial individuals who can help anticipate, track, and address issues related to conflicts of interest with very large or recurring gifts is a tool that can be used in managing ethical challenges inherent to philanthropy and psychiatry.

This framework and set of methods will, ideally, be integrated into the formal policies and procedures of the institution. The role of the advisory workgroup will depend on the institution’s needs. The workgroup may practice using these approaches and then be involved in their implementation over time. On the other hand, the workgroup may be able to turn the matter over to an appropriate person or office within the institution, such as the development office of the medical school or an administrative leader in the department of psychiatry.

Illustrations

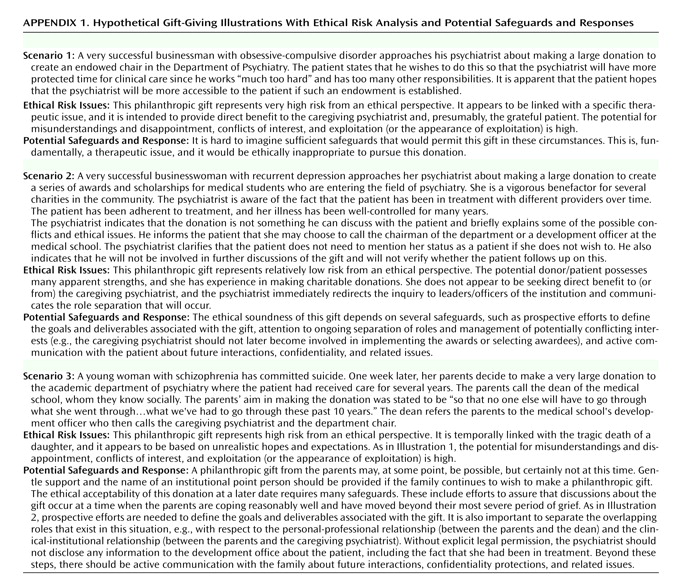

Three realistic philanthropy situations, with analyses of ethical risks and safeguards, are briefly illustrated in

Appendix 1 . As shown in each ethical decision-making scenario, it is often very helpful to start with the origin, mode, and stated goals of the initial inquiry, as this often reveals much about the ethical nature of the gift circumstance. In the first illustration of

Appendix 1, for instance, the patient approaches his psychiatrist with the idea of making a donation for an endowed position for the psychiatrist. The patient apparently can afford the generous donation but appears to be motivated by a wish to gain more of the time and attention of the clinician. This is fundamentally a therapeutic issue, not an authentic, sustained, realistically grounded “philanthropic” decision. It would be inappropriate to pursue this offer by the patient, and it is doubtful that any constellation of safeguards could make it ethically acceptable.

The second and third illustrations introduce other issues and have very different risk levels. As in the first scenario, the patient in illustration 2 also approaches her psychiatrist, but in this case the patient has a positive and realistic goal that lies outside of the therapeutic relationship (i.e., benefiting medical students). The psychiatrist then “actively manages” this interaction through the safeguards of disclosure, identification of potential conflicts, role separation, and rigorous confidentiality protections. An appropriate person (other than the caregiving psychiatrist) at the institution may then reasonably pursue this philanthropic donation. In the third scenario, the desire to make a philanthropic donation may well be sincere but also may be driven by despair, desperation, and unrealistic hopes, since it occurs in the intense context of a recent suicide. This situation is made more ethically risky because of the timing and complex overlap of social, community, institutional, professional, therapeutic, and philanthropic roles and interactions of all the individuals involved. Finally, because of the tragedy at the heart of this scenario, there are potential legal concerns for the department and the medical school. It would be inadvisable to accept the donation at the time of the initial interaction. Use of multiple safeguards would be critical to the ethical soundness of accepting this donation at a later date.

Conclusions

Undertaking these steps toward ethical philanthropy can be helpful for academic medical centers as they engage in decision-making and establish safeguards for resolving challenging ethical dilemmas and conflicts of interest. This approach presupposes that strict “hard-and-fast” rules will be insufficient to respond ethically to the complex situations that an institution may face; it places emphasis on creating a shared ‘working understanding’ that serves as the basis of decision-making and has been derived from central ethical principles and perspectives of key stakeholders.

In light of the natural concerns that will arise in relation to the controversial topic of ethical philanthropy in psychiatry in particular, the process of institutional engagement, dialogue, and shared problem-solving is especially important. Vehicles for decision-making and safeguards will serve no purpose unless they become part of the culture of the academic medical center, its major affiliates, and the neighboring community. A shared, constructive, defensible ethic will be attained only if strong and respected leaders and diverse stakeholders communicate the value of the new approach through their words, expectations, and actions. Through these efforts, greater attention will be given to the concerns of people with mental illness and academic institutions may be better able to fulfill their responsibilities to this important but neglected population now and in the future.