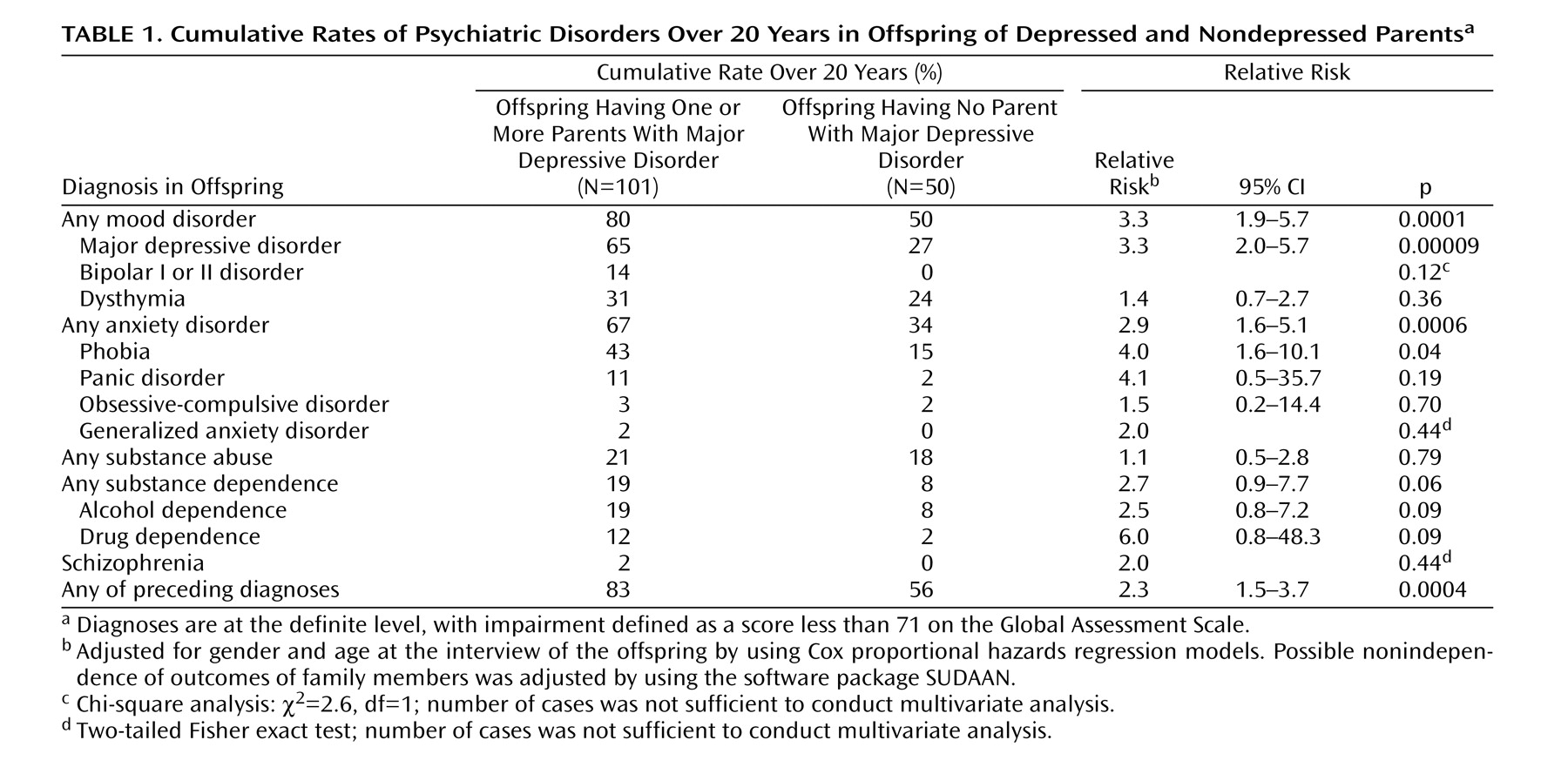

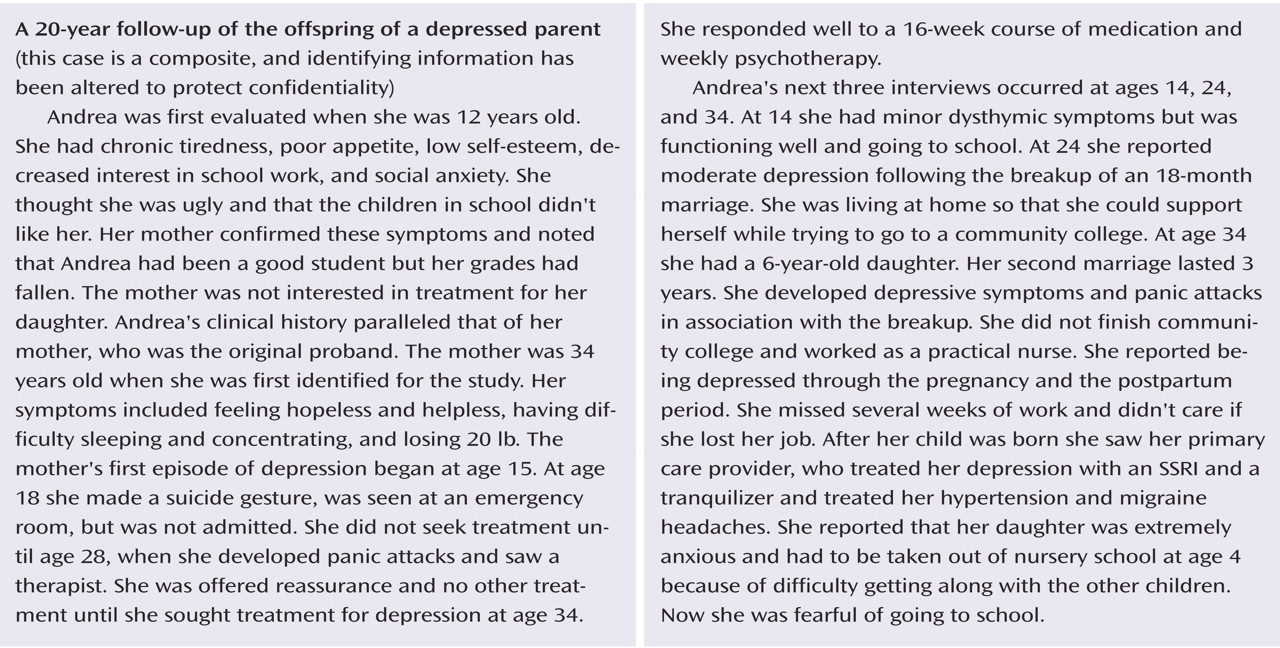

We report results from a 20-year follow-up of offspring of depressed and nondepressed parents. Numerous studies have shown that the child and adolescent offspring of depressed, as compared to nondepressed, parents are at two- to threefold greater risk for major depressive disorder and anxiety disorders

(1 –

9) . While there have been longitudinal studies of up to 40 years of adult depressed patients

(10 –

12), to our knowledge the longest follow-up of high-risk offspring is 4 years

(7) . We know of no high-risk study that has followed the offspring into adulthood.

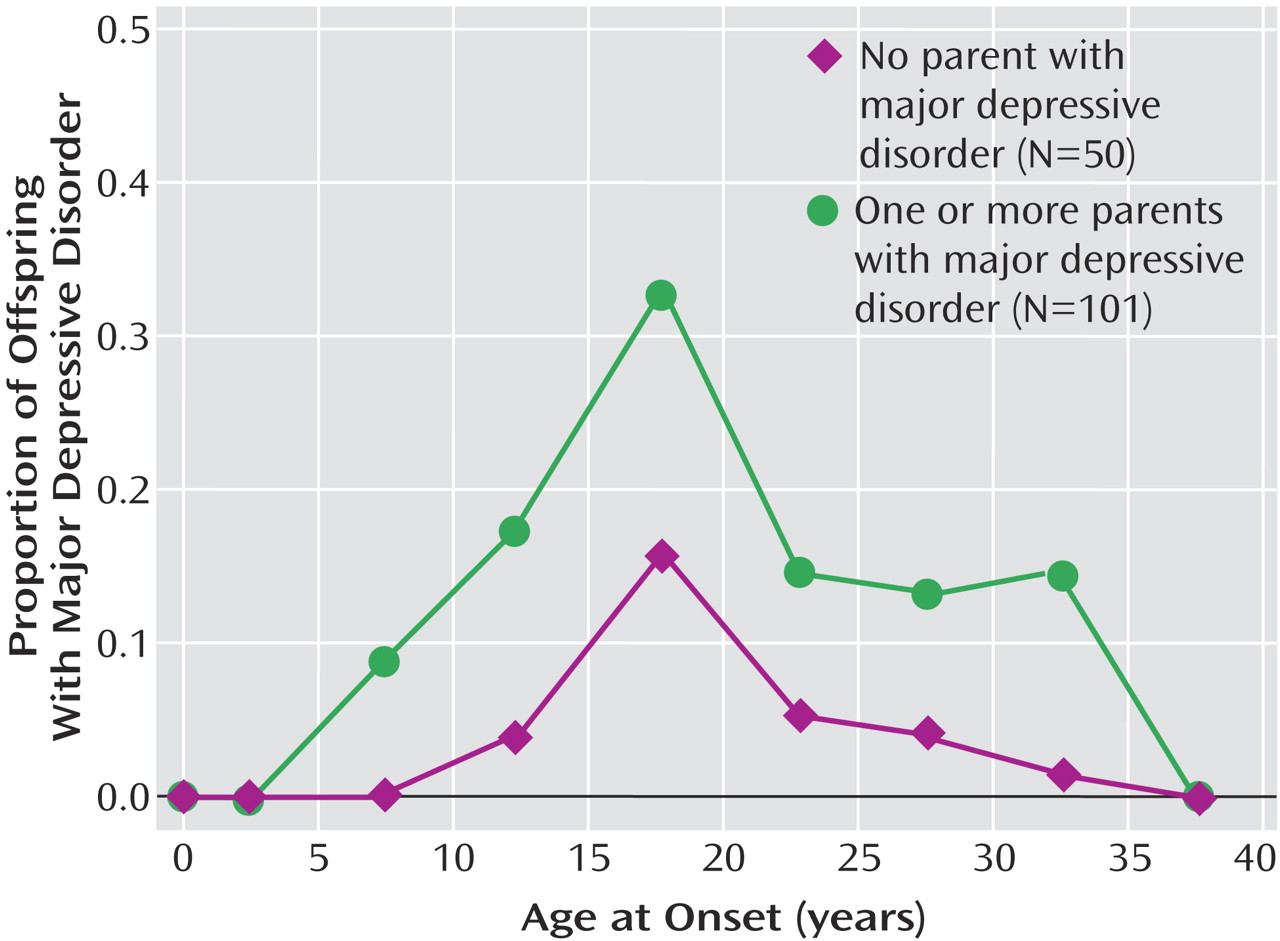

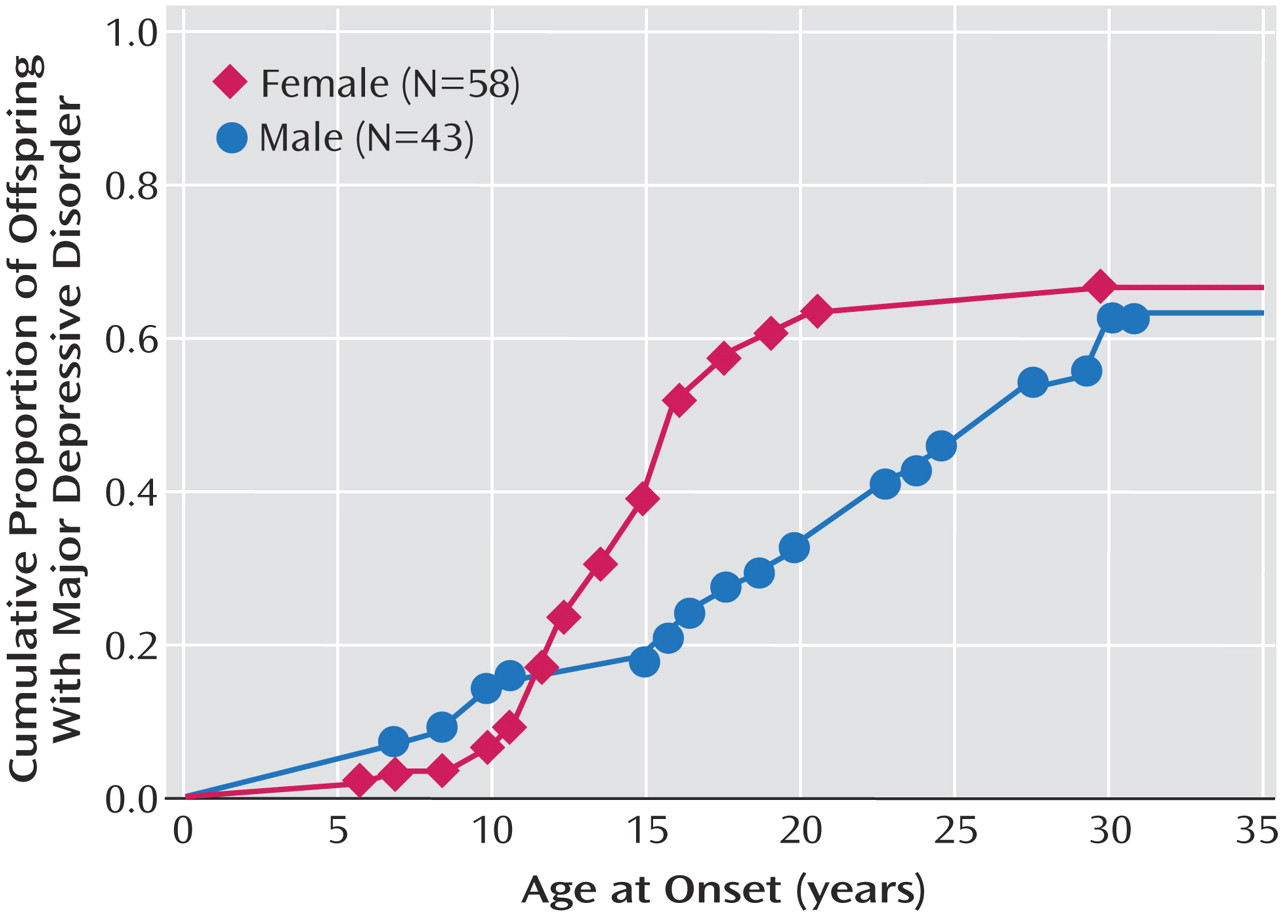

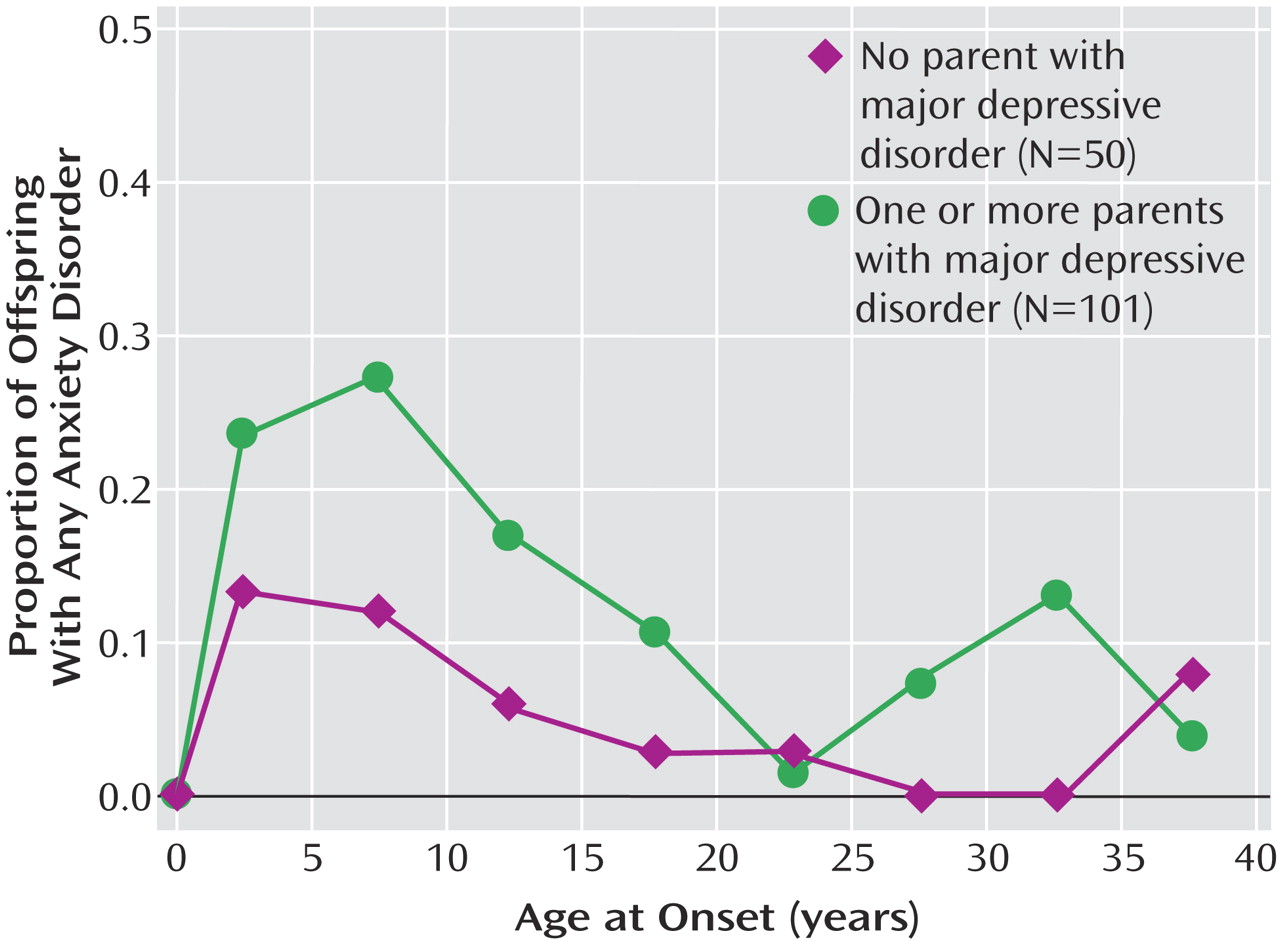

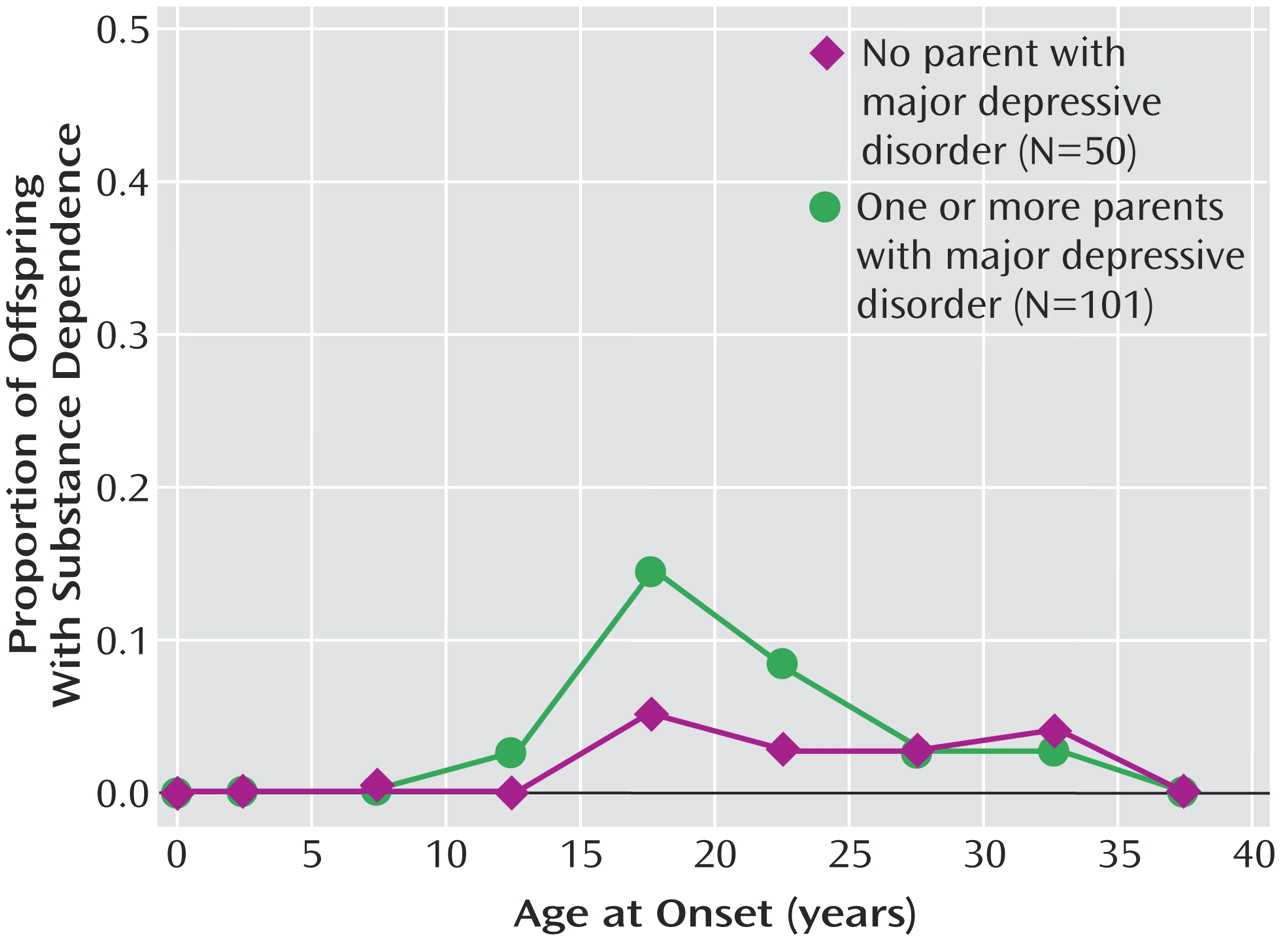

We previously reported findings from a 10-year follow-up of this cohort and showed that the highest risk for first-onset anxiety disorders was in childhood, for major depression it was in adolescence, and for substance dependence it was in adolescence and early adulthood. The peak age at onset of major depressive disorder in both high- and low-risk offspring ranged between 15 and 20 years

(13) . At the 10-year follow-up the mean age of the offspring was 26 years. The mean age at this follow-up was 35 years. At the 10-year assessment some of the offspring had not yet passed through the critical period of risk for the onset of major depression and other disorders. With the availability of a longer follow-up, age-specific and cumulative lifetime rates of psychiatric disorders and their social and medical morbidity could be estimated more precisely. Medical morbidity was of particular interest as the cohort of offspring was aging and the medical burden of depression has been well documented

(14 –

16) .

Method

In the original study, probands with moderate to severe major depressive disorder were selected from outpatient clinical specialty settings for the psychopharmacologic treatment of mood disorders. Nondepressed probands were also selected, at the same time, from an epidemiologic sample of adults from the same community. They were required to have no lifetime history of psychiatric illness, as indicated by several interviews. Full details of methods for wave 1 (baseline), wave 2 (year 2), and wave 3 (10-year follow-up) can be found elsewhere

(8,

13,

17) . We have also presented data on the third generation

(18,

19) . In this article we report data from wave 4 (about 20 years after the first wave). The procedures were kept similar across the waves, with few exceptions, to avoid introducing methods bias. The proband, spouse, and offspring were interviewed by independent interviewers who were blind to the clinical status of the previous generations and the subject’s previous history. Two spouses of participants in the normal comparison group subsequently developed a major depression between waves 2 and 3, as determined by blind independent best-estimate diagnosis (described later). These families were reclassified as having depressed probands.

Study Group

At the initial interview (wave 1) the subjects consisted of 220 offspring between the ages of 6 and 23 years from 91 families

(8) . Ten years after the initiation of the study, the families were reassessed. During the 10 years, among the 220 offspring interviewed at wave 1 there were two deaths and one offspring was found to have Down’s syndrome. Of the offspring interviewed at wave 1, 84% (182 of 217) were reinterviewed at the 10-year follow-up. There was no significant difference in attrition rate by parental diagnosis

(13) . Over the next 10 years, there were two more deaths of offspring, leaving 215 offspring of the original cohort. Of the original available cohort of offspring, 70% (151 of 215) were reinterviewed about 20 years after the initial interview. There were no significant differences between interviewed and noninterviewed offspring by age, parental diagnosis, and depression status of the offspring at the last interview. Significantly more women (58%) than men (43%) were interviewed (χ

2 =5.20, df=1, p=0.02). All interview waves were approved by the institutional review board at New York State Psychiatric Institute/Columbia University. After complete description of the study to the subjects, written informed consent was obtained from adults and assent was obtained from the minors with written consent from their parents.

Assessments

The diagnostic interviews across all waves were conducted by using a semistructured diagnostic assessment, the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia—Lifetime Version (SADS-L) for adults

(20) and the child version (K-SADS-E) modified for DSM-IV for subjects when they were between ages 6 and 17

(21,

22) . The Global Assessment Scale (GAS) was completed by the best-estimate procedure at each wave

(23) . This instrument is rated on a 0–100-point scale and provides an overall estimate of the person’s current functional adjustment based on all available information. A child’s version, the C-GAS, was used when the offspring were between ages 6 and 17

(24) . Lower scores on the GAS or C-GAS indicate more overall impairment. Life charts were used to record all episodes of illness and treatment that occurred during the period of assessment. Offspring completed the Social Adjustment Scale—Self Report, which contains questions on major areas of functioning on a 4-point scale, with higher scores indicating more impairment

(25) . Data on medical illness were collected by using a standard medical checklist (available on request) that includes 57 conditions categorized according to the site or system affected, as well as the age at onset of each one and whether medication was taken for the condition. This information was collected at each wave from the subject and, in the case of minors, from the parent about the child. The data from all waves were pooled to create a lifetime history of medical conditions. Ambiguous reports of medical problems were coded during the best-estimate process by a physician blind to the depression status of the family.

Interviewers and Best-Estimate Procedures

The diagnostic assessments were administered by trained doctoral- and master’s-level mental health professionals, who were blind to the clinical status of the parents and to previous history information. Training remained the same across waves and has been described previously

(13) . Multiple sources of information were obtained, including direct and informant interviews and medical records when available. Final diagnosis of all generations was based on the best-estimate procedure

(26) . Two experienced clinicians, a child psychiatrist (D.P.) and psychologist (H.V.) who were not involved in the interviewing, independently and blind to the diagnostic status of the previous generation or prior assessments, reviewed all the material and assigned a DSM-IV diagnosis and a GAS score. The two diagnosticians co-rated 178 randomly selected cases from all generations. Kappa scores for interrater reliability were good to excellent: major depressive disorder, 0.82; dysthymia, 0.89; anxiety disorder, 0.65; alcohol abuse/dependence, 0.94; and drug abuse/dependence, 1.00.

Statistical Analysis

Preliminary analyses of group differences in the mean values for continuous outcomes by parental depression were tested by using the t test, and categorical outcomes were compared by the chi-square test. The potential confounding effects of age and sex were adjusted for in the analysis as follows. Continuous outcomes were analyzed by using linear regression with the offspring outcome, such as the C-GAS score, as the dependent variable and parental depression as the predictor variable

(27) . Cross-sectional categorical outcomes (e.g., treatment variables) were analyzed by using logistic regression. Age and sex of offspring were considered a priori to be confounding variables and were retained in every model. These analyses were performed by applying the generalized estimating equations (GEE) approach

(28), by means of the GENMOD procedure in the SAS software package

(29), to estimate parameters and to adjust for potential nonindependence of outcomes for offspring from the same family. Survival analysis techniques adjusting for correlated survival times were used to estimate 1) the age-specific incidence rates of psychiatric disorder in 5-year intervals by using life-table methods and 2) cumulative lifetime rates of major depressive disorder in high-risk offspring by gender by means of a modified Kaplan-Meier method

(30) . Cox proportional hazards regression models

(31), modified to adjust for clustered data

(32), were used to estimate the relative risks of disorder by parental depression status while controlling for potential confounding variables, by means of the SUDAAN software package

(33) . The adjustment for clustered data was necessary to account for potential nonindependence of outcomes for offspring from the same family.

Discussion

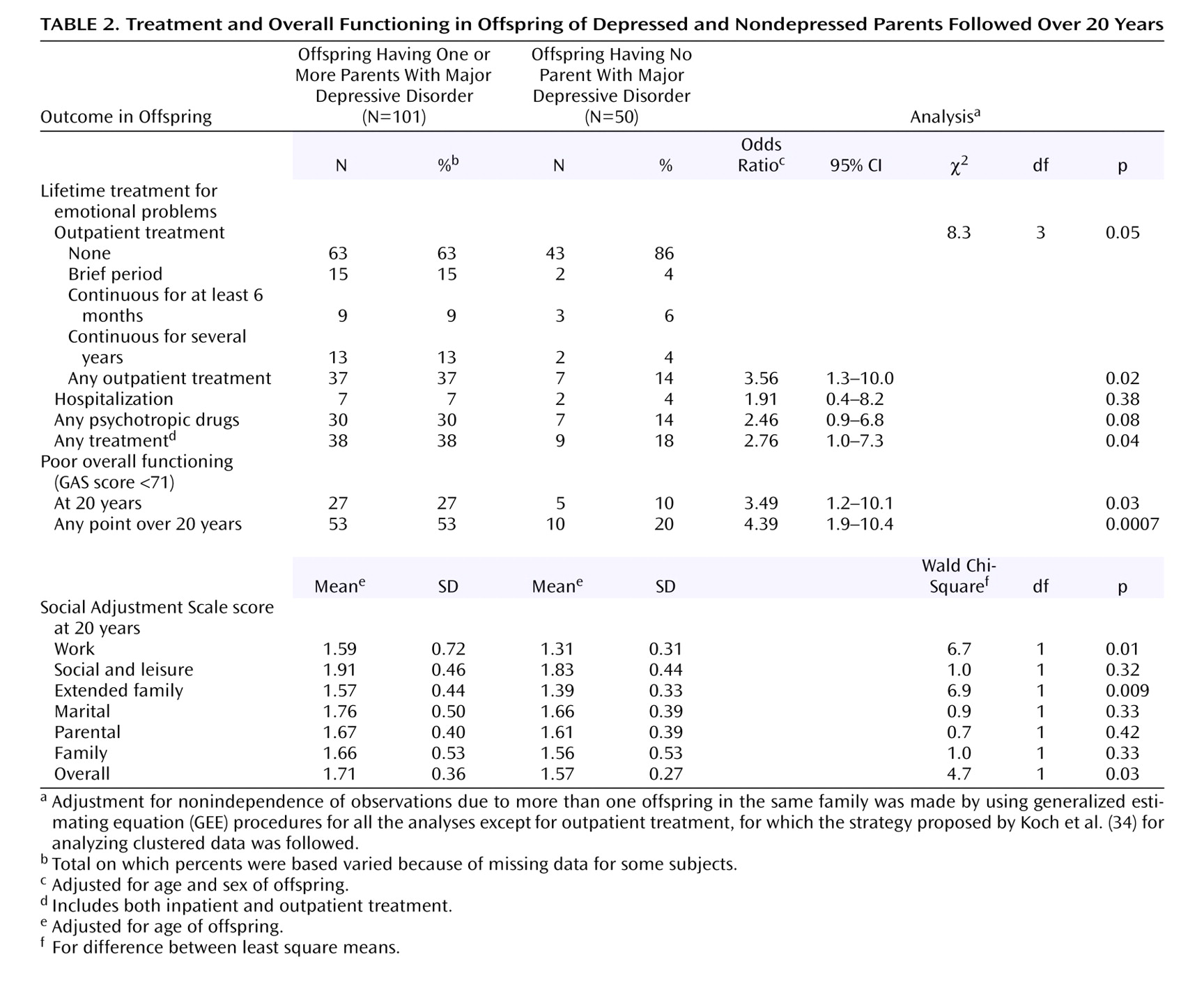

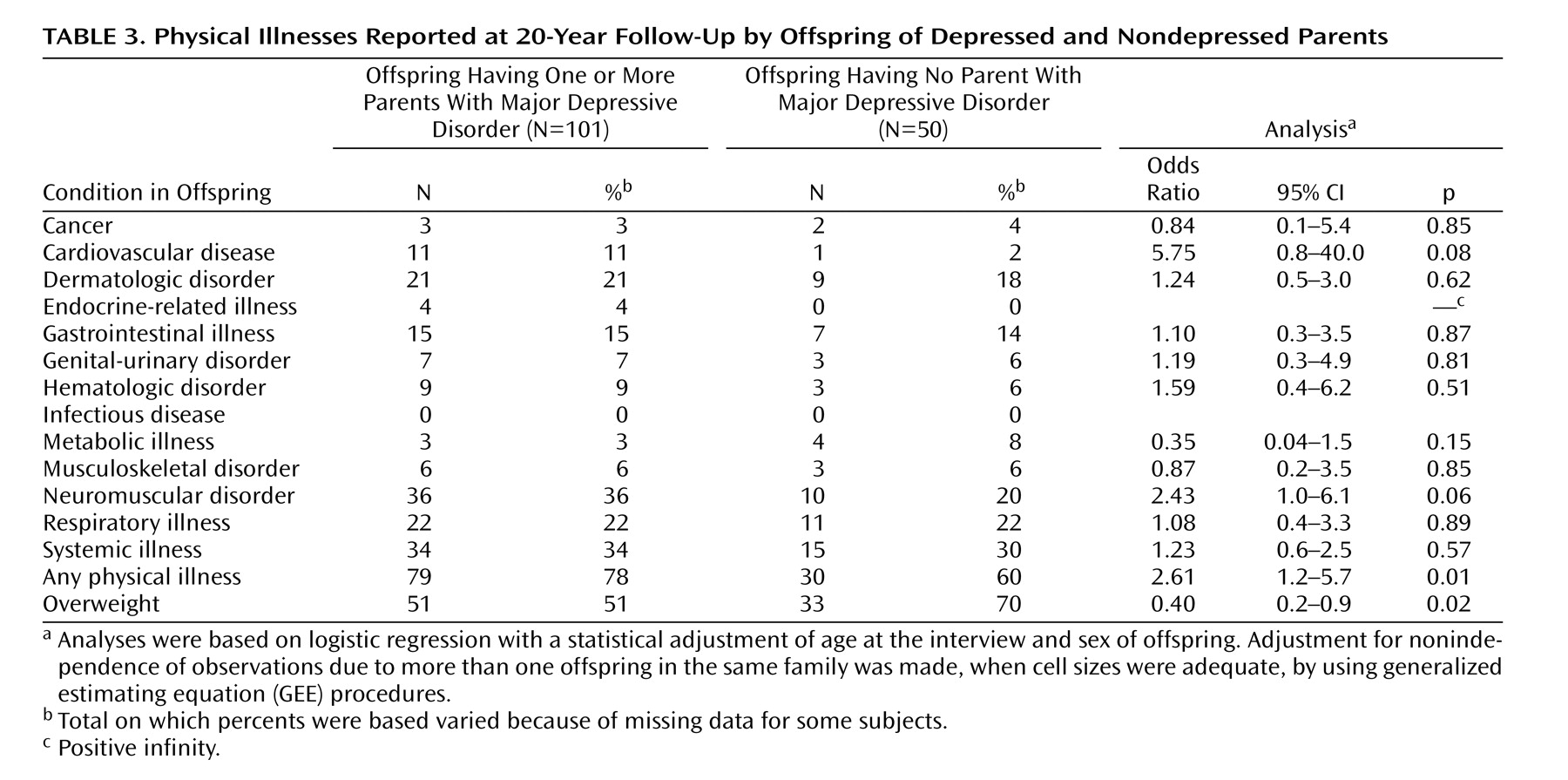

This 20-year follow-up into adulthood of the offspring of depressed and nondepressed parents confirmed previous observations about the early onset and greater risk of anxiety disorders and major depressive disorder in offspring of depressed parents and the high morbidity of major depression. The results were consistent with clinical observation of the medical morbidity of major depression as this cohort aged. The higher rates of anxiety disorders, major depression, and substance dependence in the offspring of depressed parents when they were adolescents were sustained over the follow-up, as they matured. The early onset of major depression, in adolescence, seen in the high-risk offspring was not offset by a later onset of major depression or other disorders in the low-risk offspring. Adolescence is a period of vulnerability to the onset of major depressive disorder, regardless of parental history. The peak in first onsets was before the age of 20, with anxiety disorders before puberty and with major depression and substance dependence after puberty. There was a small increase in panic disorder after age 25 in the high-risk offspring. This age at onset for panic disorder is consistent with findings from epidemiologic studies of community samples from diverse countries

(35) . The findings also showed the sustained social morbidity and the emergence of medical morbidity in the offspring of depressed parents as the offspring entered middle age. Despite the poor course, over 60% of the high-risk offspring did not receive any psychiatric treatment.

This study has several strengths and limitations. We believe that it is the longest follow-up of high-risk offspring and comparison subjects ever reported; attrition over 20 years was relatively low and all clinical assessments were made by interviewers blind to the proband’s clinical status and to the subject’s previous psychiatric history. However, there are limitations. The number of subjects was relatively small, so that detailed comparison by gender or specific disorders could not be made. There was only one comparison group. The original probands, the depressed parents, were selected from a treatment clinic and had moderate to severe major depressive disorder. We cannot generalize to a community sample, members of which may have more mild depression or may not have received treatment. The comparison subjects came from a community sample, so generalizability may be more applicable to them. Finally, the design of four waves over 20 years is reasonable for determining patterns of onset but is inadequate for determining patterns of recurrence, which requires more closely spaced assessments.

Given the caveats about the study of treated subjects, findings from the 4-year prospective community study in Munich by Lieb et al.

(7) are interesting. Direct diagnostic interviews based on the Munich version of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview were conducted on 2,548 offspring, ages 18–24, of depressed parents. A twofold higher risk of major depressive disorder, anxiety disorders, and substance abuse and greater impairment in offspring of depressed versus nondepressed parents were found. Comparable to our findings, the rate of bipolar disorder was slightly higher in the offspring of depressed than nondepressed parents (3% versus 1%). While there were higher rates of treatment in the offspring of depressed parents, the overall rates of treatment were low. Only about one-third of the offspring in the study by Lieb et al. and in ours received any psychiatric treatment.

The Munich study had the advantages of a large group of offspring and a less biased ascertainment of parents from the community. Our study had longer-term outcomes for the offspring, who are now in their mid to late 30s, and parents who were all clinically interviewed at multiple waves. The persistent impairment of depressed patients from childhood to adulthood regardless of parental history has been shown in numerous studies

(11,

12,

36,

37) . Taken together, these studies demonstrate once again that the offspring of depressed parents constitute an important high-risk group that includes many with early-onset depression. These findings are sturdy given that they are based in one study on parents from a treatment clinic and in the other on parents from a community survey.

The most intriguing finding in our study is the suggestion of more medical problems, particularly cardiovascular disease, in the high-risk offspring and the possibly higher mortality rate. Over the last few years studies have shown that 17%–27% of patients with coronary heart disease have major depression and an additional substantial number have subsyndromal symptoms (see references 16 and 38 for reviews). The most comprehensive review of studies of the relationship between coronary artery disease and depression, including 11 population-based prospective studies, indicated a 1.5 relative risk for the development of coronary artery disease conferred by major depressive disorder in patients initially free of clinical cardiac disease

(16), independent of other known risk factors for cardiac disease. Plausible biological mechanisms behind an etiologic role for major depression in coronary artery disease include altered immune, platelet, and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis functioning in depressed patients

(39) . More speculative are the observations of increased hyperintensities in magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies of elderly depressed patients

(40,

41) . These findings in patients with late-onset depression (usually after age 50 years) have led to the tentative conclusion that late-onset depression may differ in biological mediation from earlier-onset depression. The offspring in our study are undergoing MRI studies. We may be able to see whether the same hyperintensities seen in late-onset major depressive disorder are present in the subjects with early-onset depression and whether this may be related to the suggestion of more coronary-related problems.