Childhood abuse has been the focus of increasing concern, particularly when it is sexual or severely physical. This has been further reinforced by studies that suggest that abuse produces enduring effects on brain development

(1) . While sexual abuse has come under intense scrutiny as a psychiatric risk factor, emotional maltreatment may be a more elusive and insidious problem. Emotional abuse encompasses several forms of childhood maltreatment, such as the witnessing of domestic violence and exposure to verbal aggression

(2) . Generally, exposure to verbal aggression has received little attention as a specific form of abuse, although it may be at least as important as witnessing domestic violence. In one large national study, Vissing et al.

(3) found that 63% of American parents reported one or more instances of verbal aggression, such as swearing at and insulting their child. Children who were the target of frequent verbal aggression exhibited higher rates of physical aggression, delinquency, and interpersonal problems than other children

(3) .

Maternal verbal abuse during childhood has been associated with a markedly higher risk for development of borderline, narcissistic, obsessive-compulsive, and paranoid personality disorders

(4) . These associations remained significant after control for temperament, physical abuse, sexual abuse, neglect, parental psychopathology, and co-occurring psychiatric disorders

(4) . Verbal abuse may also have more lasting consequences than other forms of abuse

(5) and, in combination with physical abuse and neglect, produce the most dire outcome

(6) . However, child protective service agencies, doctors, and lawyers are most concerned about the impact and prevention of physical or sexual abuse

(7,

8) .

We sought to answer two questions. First, is there a discernible impact of exposure to childhood verbal aggression in the absence of physical abuse, sexual abuse, or exposure to domestic violence? Second, what are the relative psychiatric consequences of childhood exposure to verbal aggression, witnessing domestic violence, physical abuse, and sexual abuse, experienced either alone or in combination? Dissociation and “limbic irritability” were selected as two primary variables for analysis, as previous research had shown robust correlations between dissociation and hippocampal size

(11) and between limbic irritability and blood flow to the cerebellar vermis as assessed with functional magnetic resonance imaging

(12) . We also assessed the effects of exposure on symptoms of depression, anxiety, and anger-hostility.

Results

Effects on Limbic Irritability

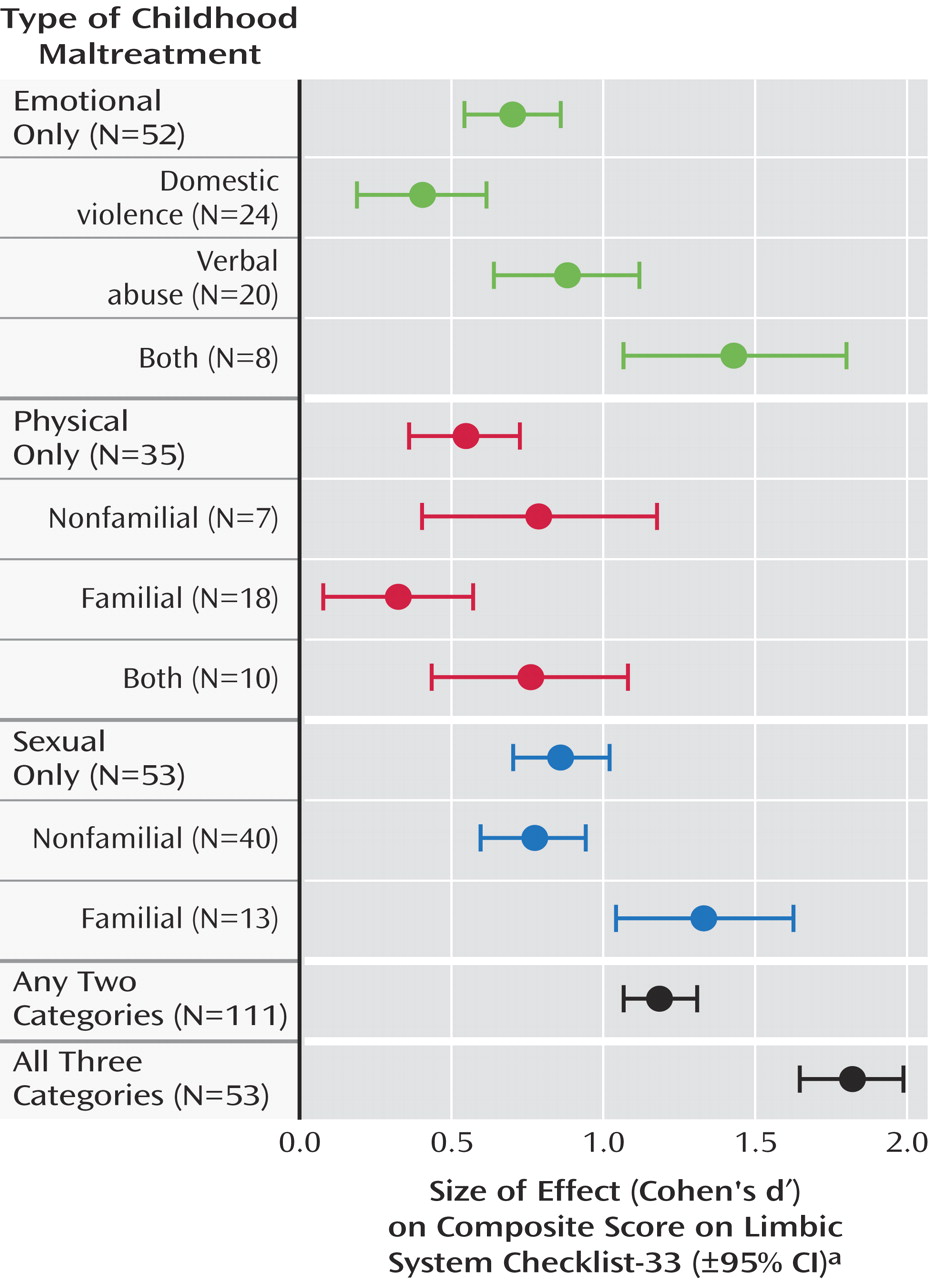

As seen in

Figure 1, there were robust effects of each of the five broad abuse categories (emotional only, sexual only, physical only, any two, all three) on ratings on the Limbic System Checklist-33 (F=21.46, df=5, 542, p<10

– 15, n

2 =0.149). There was no effect of gender on this measure (F=1.13, df=5, 542, p>0.30). Subjects in all of the broad abuse categories had ratings that were higher than those of subjects who had never experienced maltreatment. Emotional abuse had a moderately large effect on the rating of limbic irritability (d′=0.703, 95% CI=0.548–0.858; t=4.95, df=300, p<10

– 5 ). Subjects who were exposed only to emotional abuse had ratings that were as high as those of subjects who were exposed only to physical abuse (t=0.72, df=85, p>0.40) or only to sexual abuse (t=–0.83, df=102, p>0.40).

Subjects who were exposed to two different categories of abuse had higher scores for limbic irritability than subjects exposed to emotional abuse only (t=2.65, df=161, p<0.01) or physical abuse only (t=3.07, df=144, p<0.003). Subjects who reported exposure to all three categories of abuse had significantly higher scores than those exposed to any single category of abuse.

Limbic irritability was also significantly affected by exposure to any of the more specific types of abusive experience within each broad abuse category (verbal, nonfamilial sexual, etc.) (F=4.44, df=8, 372, p<10 –4 ). Exposure to verbal abuse had a relatively large effect size (d′=0.876, 95% CI=0.641–1.111), whereas witnessing domestic violence had a moderate effect size (d′=0.403, 95% CI=0.189–0.617), although this difference could have occurred by chance (t=1.49, df=42, p=0.15). It is interesting that combined exposure to verbal abuse and witnessing domestic violence had a very large effect size (d′=1.428, 95% CI=1.063–1.793), which was essentially equal to the effect size of familial sexual abuse (d′=1.333, 95% CI=1.043–1.623).

Effects on Dissociative Experiences

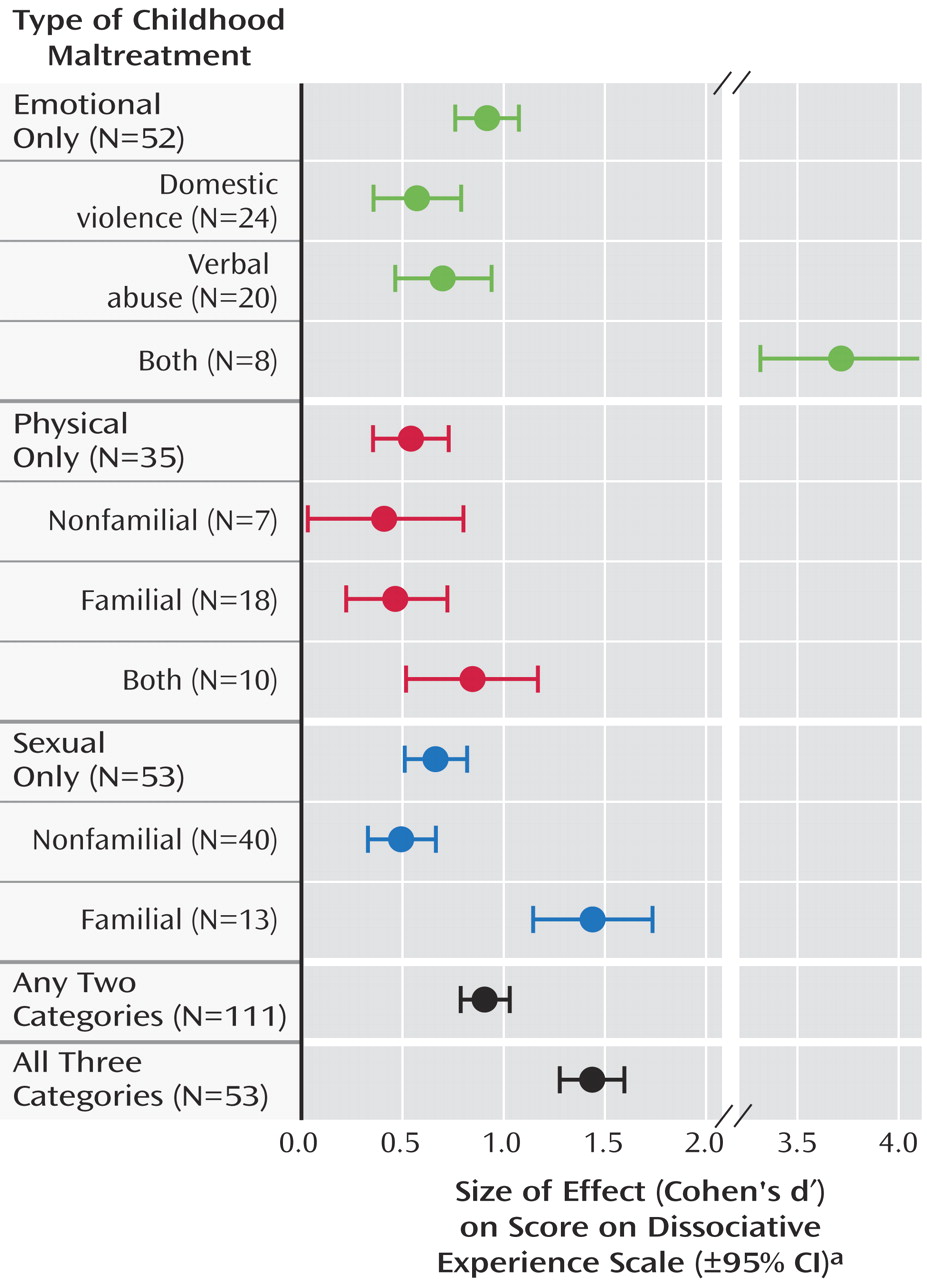

As seen in

Figure 2, there were robust effects of the broad abuse categories on dissociation (F=13.63, df=5, 540, p<10

–11, n

2 =0.105), and they did not differ between genders (F=1.88, df=5, 540, p<0.10). Emotional abuse had a large effect on Dissociative Experience Scale ratings (d′=0.910, 95% CI=0.753–1.067). Exposure to physical abuse and sexual abuse had moderate effects (d′=0.533, 95% CI=0.351–0.715, and d′=0.659, 95% CI=0.505–0.813, respectively). Exposure to two different broad categories of abuse was associated with a large effect size (d′=0.902, 95% CI=0.783–1.021) that was similar to the effect size for emotional abuse. Exposure to all three categories was associated with a very large effect size (d′=1.431, 95% CI=1.269–3.024) that was greater than the effect of exposure to physical abuse (t=2.97, df=86, p<0.005) or sexual abuse (t=2.55, df=104, p<0.02) and marginally greater than the effect of emotional abuse alone (t=1.92, df=103, p=0.06).

Exposure to verbal abuse alone and witnessing of domestic violence had moderately strong effects on dissociation ratings (d′=0.690, 95% CI=0.456–0.924, and d′=0.564, 95% CI=0.349–1.343, respectively). Subjects exposed to both verbal abuse and domestic violence (but no other form of maltreatment) had Dissociative Experience Scale scores 4.5 times as high as those of the nonabused subjects (d′=3.719, 95% CI=3.324–4.114). In this limited study group, the effect of combined exposure to verbal abuse and witnessing domestic violence had more impact on dissociation ratings than exposure to familial sexual abuse (t=2.42, df=19, p=0.02).

Effects on Anxiety Symptoms

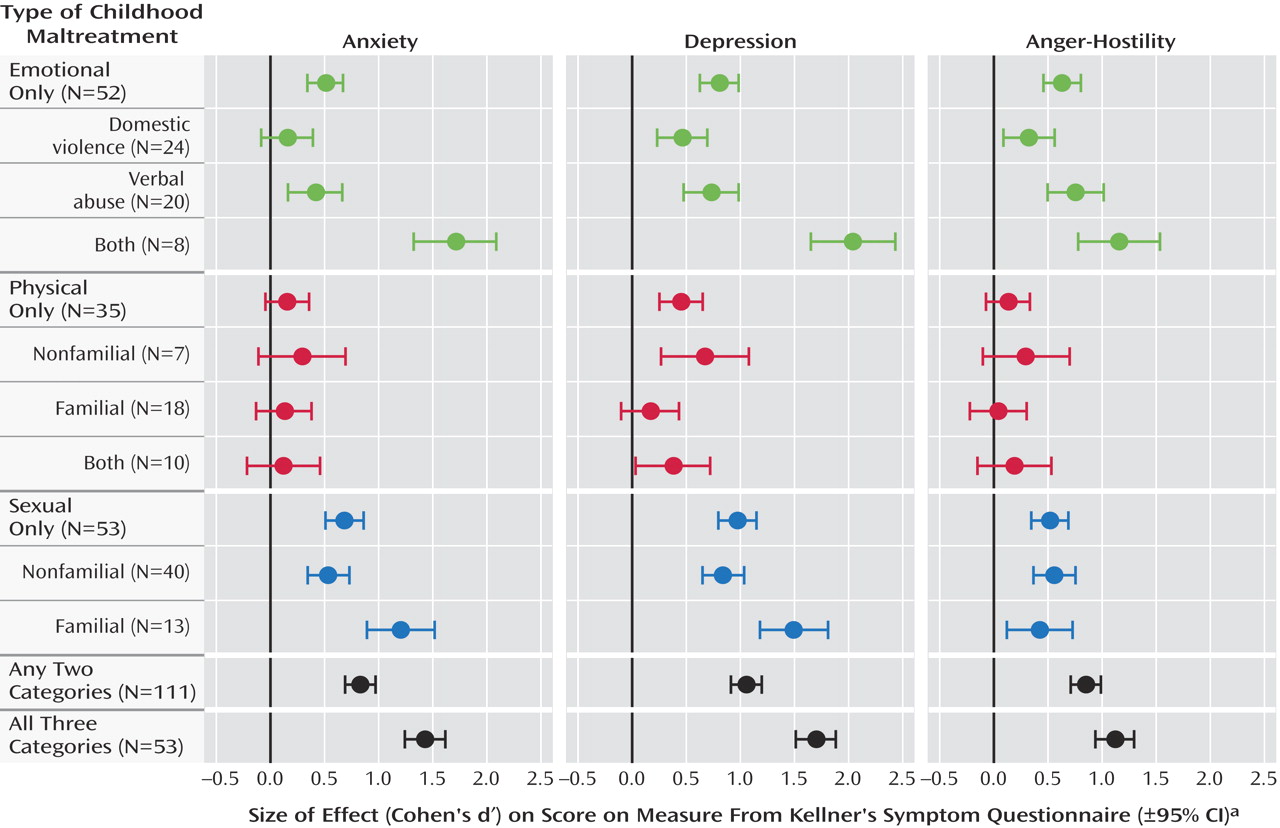

As seen in

Figure 3, there were robust effects of the broad abuse categories on anxiety (F=14.36, df=5, 541, p<10

–12, n

2 =0.109), which did not differ between genders (F=1.53, df=5, 541, p<0.20). Emotional abuse alone and sexual abuse alone had moderate effects (d′=0.510, 95% CI=0.356–0.664, and d′=0.684, 95% CI=0.530–0.838, respectively). Exposure to physical abuse alone exerted only a small and nonsignificant effect (d′=0.158, 95% CI=–0.023–0.339; t=0.81, df=283, p=0.16). Exposure to two different broad categories of abuse was associated with a large effect size (d′=0.832, 95% CI=0.714–0.950), and exposure to all three abuse categories was associated with a very large effect size (d′=1.429, 95% CI=1.267–1.591) that was significantly greater than the effect of exposure to any single category of abuse.

Exposure to verbal abuse alone and witnessing domestic violence had relatively weak effects on anxiety ratings (d′=0.422, 95% CI=0.189–0.655, and d′=0.158, 95% CI=–0.056–0.372, respectively). Combined exposure to verbal abuse and witnessing domestic violence had a greater than additive effect (d′=1.718, 95% CI=1.351–2.085). Subjects exposed to both verbal abuse and domestic violence (but no other forms) had anxiety scores that were 2.2 times as high as those of the nonabused subjects (t=4.76, df=256, p<10 –6 ). The effect of combined exposure to verbal abuse and witnessing of domestic violence was as great as the effect of exposure to familial sexual abuse (d′=1.204, 95% CI=0.915–1.493).

Effects on Depression Symptoms

There were robust effects of the broad abuse categories on depression (F=15.91, df=5, 541, p<10 –12, n 2 =0.121), and they were consistent across genders (F=0.58, df=5, 541, p>0.70). Emotional abuse alone and sexual abuse alone had large effects (d′=0.804, 95% CI=0.648–0.960, and d′=0.971, 95% CI=0.815–1.127, respectively). Exposure to physical abuse alone exerted a moderate effect (d′=0.452, 95% CI=0.271–0.633). Exposure to all three categories exerted a very large effect (d′=1.696, 95% CI=1.530–1.862), which was significantly greater than the effect of exposure to any single category of abuse.

Exposure to verbal abuse alone and witnessing of domestic violence had moderately strong effects on depression (d′=0.730, 95% CI=0.496–0.964, and d′=0.463, 95% CI=0.249–0.677, respectively). Combined exposure to verbal abuse and witnessing domestic violence had a greater than additive deleterious effect (d′=2.042, 95% CI=1.672–2.412). Subjects who were exposed to this combined type of emotional abuse had depression scores that were 2.8 times as high as those of the nonabused subjects (t=5.66, df=256, p<10 –8 ). The effect of combined exposure to verbal abuse and witnessing domestic violence was greater than or equal to the effect of exposure to familial sexual abuse (d′=1.494, 95% CI=1.202–1.786) or exposure to all three categories of abuse (d′=1.696, 95% CI=1.530–1.862).

Effects on Symptoms of Anger-Hostility

There were robust effects of the broad abuse categories on anger-hostility (F=15.18, df=5, 541, p<10 –12, n 2 =0.119). Emotional abuse alone and sexual abuse alone exerted moderate effects (d′=0.630, 95% CI=0.475–0.785, and d′=0.520, 95% CI=0.367–0.673, respectively). Physical abuse alone exerted only a weak and not statistically significant effect (d′=0.131, 95% CI=–0.049–0.311; t=0.73, df=283, p>0.40) and was eclipsed by the effects of exposure to emotional abuse (t=2.08, df=85, p=0.04). Combined exposure to any two categories of abuse had a large effect size (d′=0.851, 95% CI=0.733–0.969), and exposure to all three categories had an even larger effect size (d′=1.121, 95% CI=0.963–1.279).

Exposure to verbal abuse alone had a moderately strong effect on anger-hostility (d′=0.758, 95% CI=0.523–0.993), and these subjects had scores that were 58% greater than those of the nonabused individuals (t=3.25, df=268, p<0.002). Witnessing domestic violence had a relatively weak effect on these symptoms (d′=0.327, 95% CI=0.113–0.541), and the scores of subjects with this childhood experience were only 25% higher than those of the comparison subjects (t=1.53, df=272, p=0.13). Combined exposure to verbal abuse and witnessing domestic violence had an additive deleterious effect (d′=1.156, 95% CI=0.793–1.519). The effect of combined exposure to verbal abuse and domestic violence was at least as great as the effect of exposure to familial sexual abuse (d′=0.427, 95% CI=0.142–0.712) and was comparable to the effect of exposure to all three types of abuse (d′=1.121, 95% CI=0.963–1.279).

History of Treatment

The impact of multiple exposures to different forms of maltreatment was also mirrored in the percentage of subjects reporting a past history of psychiatric treatment (χ 2 =40.4, df=5, p<10 –7 ). Previous psychiatric care was reported by 3% of the subjects with no history of maltreatment, 0% of those with a history of physical abuse alone, 8% of those who were exposed to emotional maltreatment, and 9% of those who were exposed to sexual abuse. In contrast, 18% of the subjects exposed to any two types of maltreatment and 25% of those exposed to all three categories reported a past history of psychiatric care.

Discussion

Childhood exposure to parental verbal aggression was associated, by itself, with moderate to large effects on measures of dissociation, limbic irritability, depression, and anger-hostility. Exposure to verbal aggression was associated with numerically larger effects on scores on the Limbic System Checklist-33 and Kellner Symptom Questionnaire than was exposure to domestic violence, although these differences could have occurred by chance. Combined exposure to verbal abuse and witnessing of domestic violence was associated with extraordinarily large adverse effects, particularly on dissociation. This finding is consonant with studies that suggest that emotional abuse may be a more important precursor of dissociation than is sexual abuse

(18) .

These findings raise the possibility that exposure to verbal aggression may be a stressor that affects the development of certain vulnerable brain regions in susceptible individuals, resulting in psychiatric sequelae

(1) . Alternatively, exposure to verbal aggression in childhood may put into force a powerful negative model for interpersonal communication, which is then incorporated as a behavioral response in future relationships. Toth and Cicchetti

(19) proposed a cascade of interpersonal events in maltreated children that begins with insecure attachment relationships, moves to negative representational models of the self and of the self in relation to others, and eventuates in impaired perceived competence, poorer social functioning, and lowered self-esteem. Similarly, Crittenden

(20) found that exposure to abuse and neglect affects attachment patterns and coping strategies. These possibilities are not mutually exclusive, and each could contribute in important ways.

In the present study group, with our definitions of abuse it appeared that emotional maltreatment was more closely associated with psychiatric sequelae than was physical abuse. It is possible that we would have observed a more deleterious effect of physical abuse if we had adopted a stricter definition. We are conducting further studies with additional measures to test this possibility.

Combined exposure to different categories of abusive experiences often equaled or exceeded the impact of exposure to familial sexual abuse. This is of great importance as it suggests that combined exposure to less blatant forms of abuse may be just as deleterious as the most egregious acts we confront. Fifty-nine percent of the subjects in the present study with a history of maltreatment had been exposed to more than one type of abuse.

These findings are concordant with the results of a large-scale epidemiological study designed to assess the prevalence and health impact of early trauma experiences, the Adverse Childhood Experiences Study

(21) . All of the publications resulting from this work point to a relationship between self-reported early exposure to adversity and subsequent problems, including depression

(9), attempted suicide

(10), substance abuse, and an array of medical disorders. A dose-response relationship was observed such that the greater the number of childhood adverse experiences, the greater the risk for a negative health outcome in adulthood. Macfie et al.

(22) also reported that exposure to multiple forms of trauma, along with severity and chronicity, was predictive of subsequent psychopathology.

The mechanisms underlying the additive or synergistic effects of exposure to different types of abuse are unknown. It is possible that an additive or greater effect may emerge because abuse at home could prevent a child from seeking help or reassurance from his or her parents when confronted with abuse outside the home. Alternatively, individuals exposed to different types of abuse may experience them at different developmental stages, which would increase the likelihood that abuse occurred during key sensitive periods. A third hypothesis is that exposure to multiple types of abuse increases the frequency of exposure and that, in addition to genetic factors, a certain minimal number of exposures is necessary for the development of an adverse outcome

(23) .

The present study is limited by our reliance on self-reports. How do we know if the participants’ abuse histories are valid? We are sensitized to this issue by the debate surrounding false or repressed memories. However, the issue of repressed memories is unlikely to be a significant factor in this research protocol as the events reported were current memories and the study provided no incentive for the subjects to fabricate a history of abuse, as they were never informed of our screening criteria. While we are concerned about potential fabrications, research suggests that the overall bias is in the opposite direction—individuals are more likely to minimize or deny their adverse childhood experiences

(24) . Positive reports of maltreatment can be corroborated

(25) . While retrospective self-report studies constitute the vast bulk of the literature on the effects of early abuse on adults, prospective studies that confirm its impact are emerging

(23,

26) .

We cannot exclude the possibility that individuals who have a relatively high degree of current psychiatric symptoms may report aspects of their childhood in a more negative light than do individuals who are free of such symptoms

(27) . It is also possible that exposure to familial emotional, physical, or sexual abuse is highest in families with mental illness, and thus, genetic factors could contribute to the higher symptom scores we observed in our subjects with exposure to familial abuse. Studies of twins discordant for childhood sexual abuse provide a potentially powerful means of assessing the respective contribution of childhood sexual abuse while controlling for genetic vulnerabilities and shared environment. Kendler et al.

(28) reported that the twins with childhood sexual abuse had an overall increased risk for major depression and a substantially increased sensitivity to the depressogenic effects of other stressful life events.

We have used the term “association” to describe the relationship between symptom ratings and retrospective self-reports of abuse. While we hypothesize that there may be a causal relationship, there are other legitimate ways to interpret the data. Indeed, it may be the case that the relationship between abuse reports and symptoms is due to a combination of direct effects of early stress, recall bias, and increased genetic load.

Another limitation is that our probe question for exposure to domestic violence was very broad, and so the definition of domestic violence may not be comparable to definitions in studies that specifically focused on observations of mothers being battered. We know from more detailed assessment of 54 individuals (16 men and 38 women, mean age=20.8 years, SD=1.1) who responded positively to this general probe question on the witnessing of serious domestic violence that 65% had witnessed their mothers being threatened or assaulted, 43% had witnessed siblings being threatened or assaulted, and 17% had witnessed threats or assaults of their fathers. Further, 24% had witnessed the severe beating of the person involved. The effect of exposure to domestic violence might have been greater had we used a more specific and limited definition.

Finally, representative sampling techniques were not used. This means that the impact of maltreatment observed may not generalize to other groups. Sixty-five subjects from the group were recruited for additional studies and went through structured diagnostic interviews, neuropsychological testing, and imaging protocols. They had an average Hollingshead two-factor socioeconomic status of 4.0 (SD=0.8) (upper middle class).

In all likelihood, the overall degree of psychopathology was probably lower in our healthy, predominantly collegiate study group than would be found in a representative sample, although the relative effects of exposure to different forms of abuse should generalize to other populations.

Verbal abuse was associated with effect sizes that were numerically greater than those associated with witnessing domestic violence or familial physical abuse. However, witnessing domestic violence and physical abuse can qualify as a category A(1) traumatic event necessary for the DSM-IV diagnosis of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), while exposure to verbal abuse cannot. We wonder, particularly in children, if threats to one’s mental integrity and sense of self can also be traumatizing. Bremner et al.

(29) made an interesting observation: “Surprisingly, emotional abuse items, such as being often shouted at, appeared to have severe consequences in terms of risk for PTSD.” The specific role of verbal abuse in the development of PTSD has yet to be determined. Research is needed to evaluate whether such exposure is causative or whether it contributes to the development of PTSD by amplifying the effects of exposure to traumatic events.

It will likely come as no surprise to clinicians that parental verbal aggression is associated with psychiatric symptoms. The potential effects of exposure to verbal abuse, by itself and in combination with other forms of abuse, need to be carefully considered in research studies focusing on the effects of early experience. Individuals interested in the welfare of maltreated children should not underestimate the consequences of verbal abuse. Finally, careful attention should be given to the number of different types of traumatic experiences a child was exposed to, as this may be even more critical than the specific type of abuse.