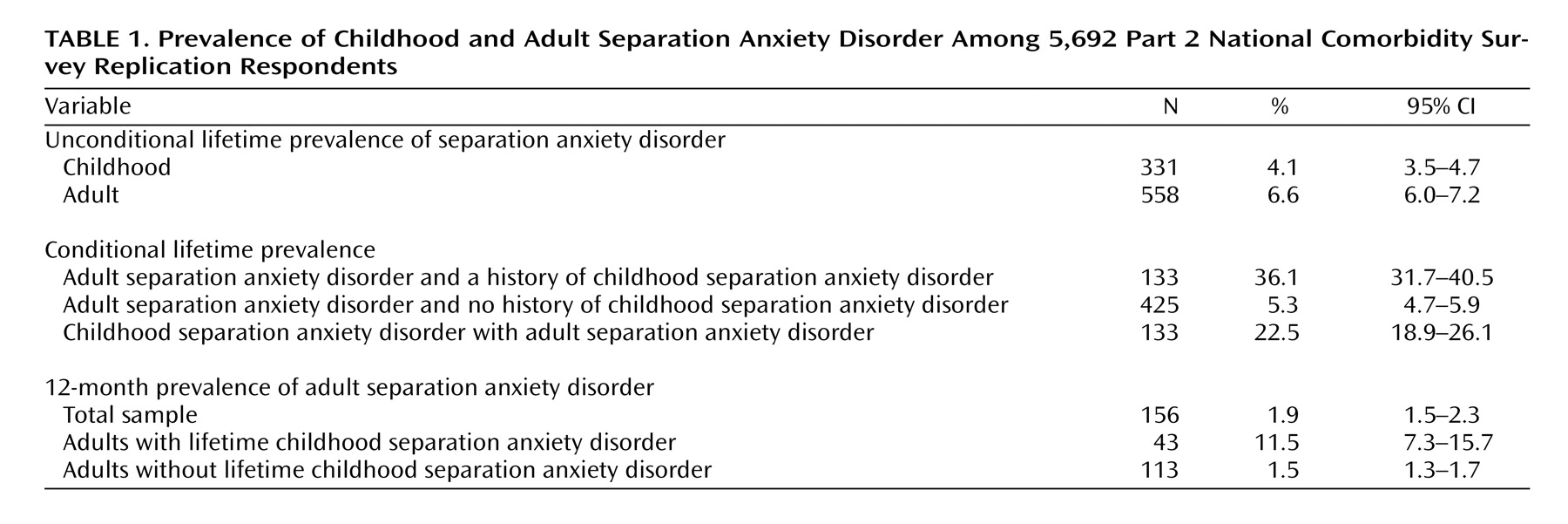

Two limitations of the study are noteworthy. First, the potentially distorting influence of retrospective recall bias cannot be ruled out in interpreting reports about childhood separation anxiety disorder. Second, diagnoses were based on unvalidated fully structured interviews administered by lay interviewers rather than by clinical interviewers. This could be an especially important limitation for a disorder such as separation anxiety disorder, in which clinical judgment may be needed to determine whether the degree of anxiety about separation from an attachment figure truly is excessive in relation to the respondent’s life situation or developmental phase or if the symptoms are better explained by another mental disorder. Because of these limitations, these results should be considered provisional. Within the context of these limitations, to our knowledge, we presented the first nationally representative data on the descriptive epidemiology of adult separation anxiety disorder. The 4.1% estimated prevalence of childhood separation anxiety disorder is similar to previously published estimates

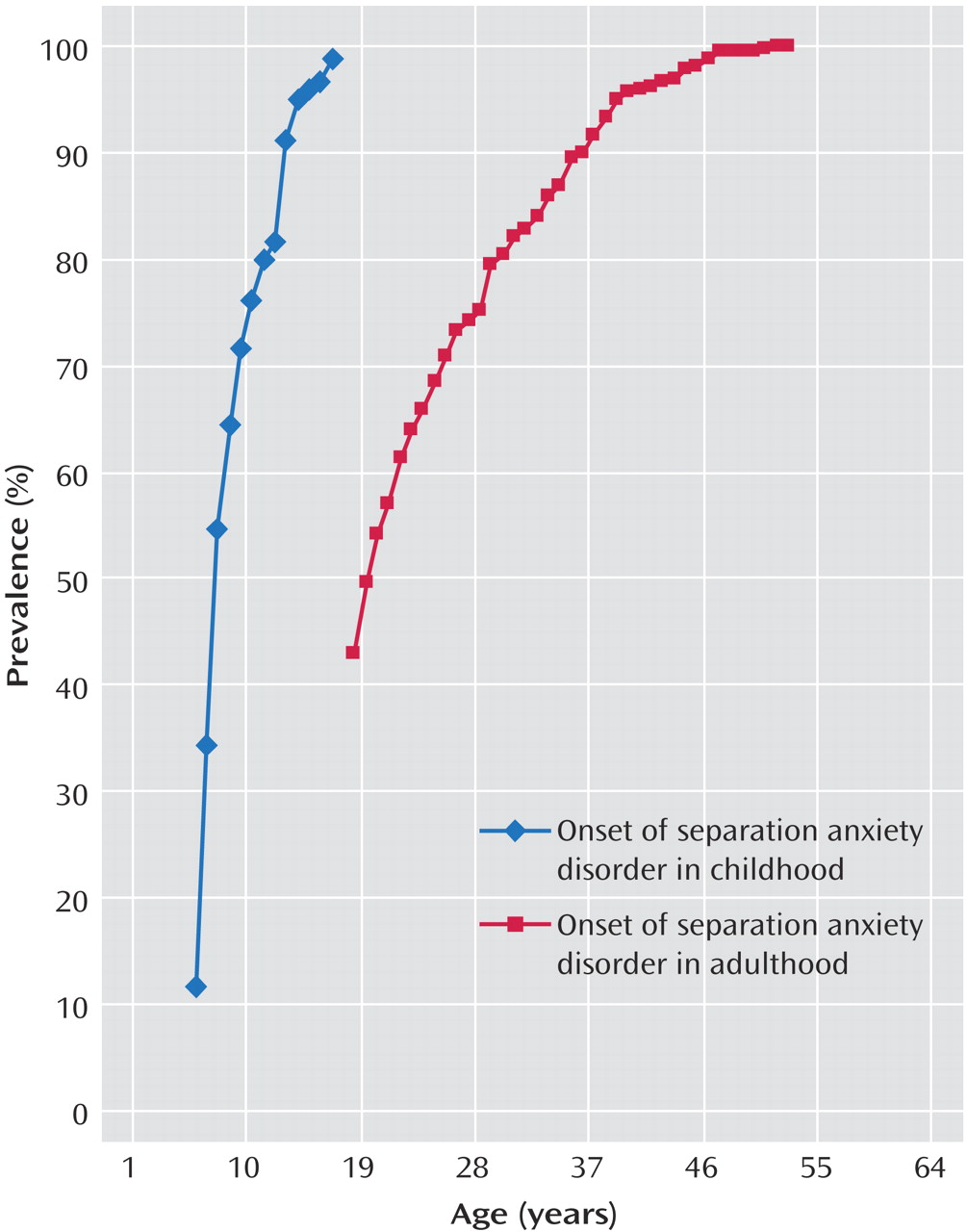

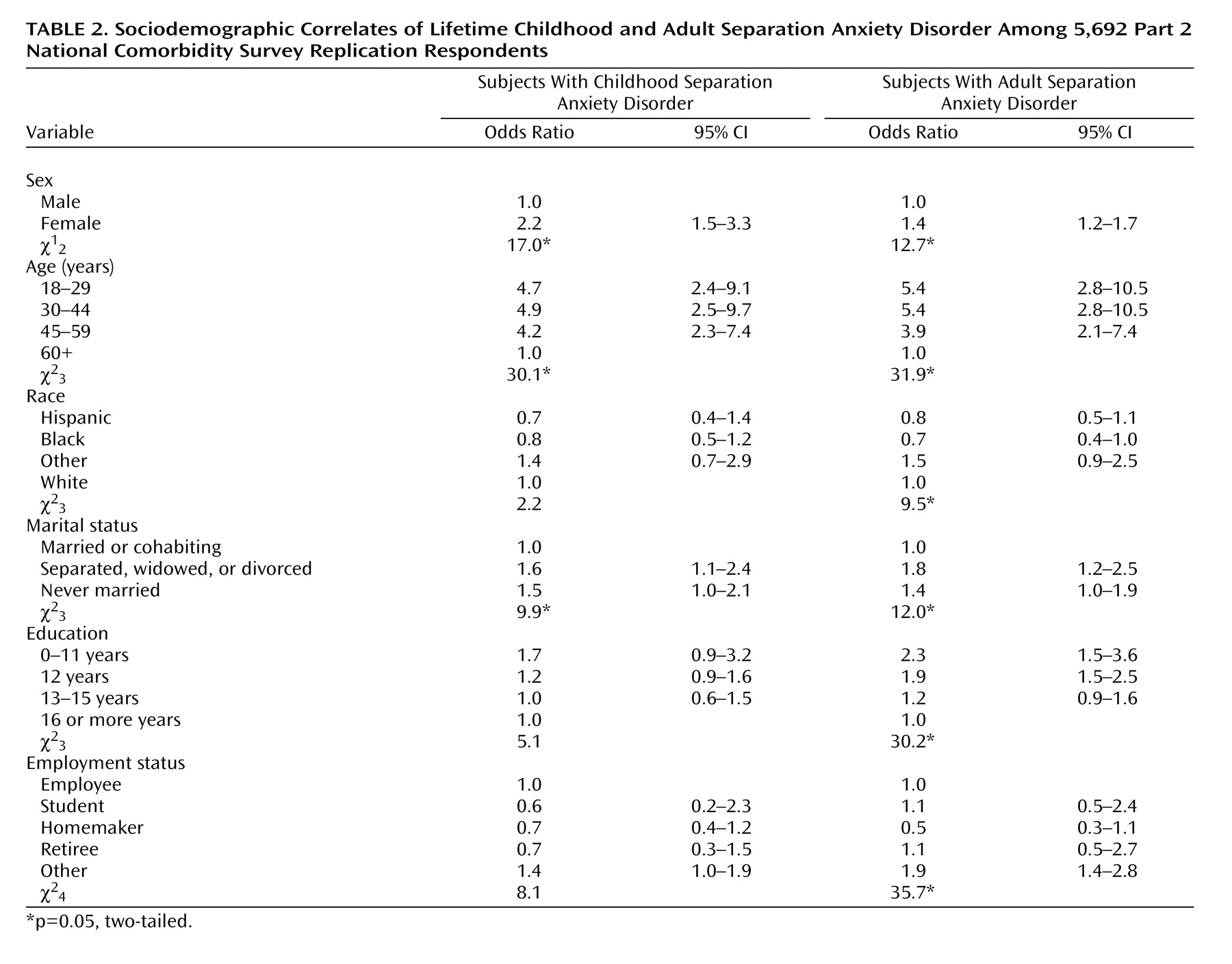

(26) . However, contrary to suggestions in DSM-IV-TR, the estimated lifetime prevalence of adult separation anxiety disorder (6.6%) was higher than the estimated lifetime prevalence of childhood separation anxiety disorder. In addition, the vast majority of respondents classified as having adult separation anxiety disorder reported first onset in adulthood rather than childhood, even though a substantial proportion of the respondents classified as childhood cases persisted into adulthood. These results call into question DSM-IV-TR representation of adult separation anxiety disorder. The NCS-R finding that estimated separation anxiety disorder is more prevalent among women than men is consistent with previous research on childhood separation anxiety disorder

(11,

12,

26,

27) . That the female-male odds ratio is lower for estimated adult (1.4) than childhood (2.2) cases could mean either that persistence into adulthood is higher for males than females or that males are more likely than females to have first onset in adulthood. More detailed analyses (results not shown) found that only the latter process is at work. The finding that estimated adult separation anxiety disorder is associated with roughly doubling of the odds of low (0–12 years) education, unemployment, and marital disruption is consistent with the suggestion in the clinical literature that separation anxiety disorder can be seriously impairing, although temporal and causal priority were not sorted out in the cross-sectional analyses of these sociodemographic correlates. The odds of being not married are elevated among both respondents with estimated childhood separation anxiety disorder and those with estimated adult separation anxiety disorder. This result indirectly suggests that estimated childhood separation anxiety disorder might be a risk marker for subjects remaining unmarried and, once married, for marital instability. Education and occupation, in comparison, were related to estimated adult separation anxiety disorder but not to estimated childhood separation anxiety disorder. The failure to find an association of estimated childhood separation anxiety disorder with these core indicators of socioeconomic status differs from the consistent finding in child epidemiological studies that separation anxiety disorder is strongly related to low parental socioeconomic status

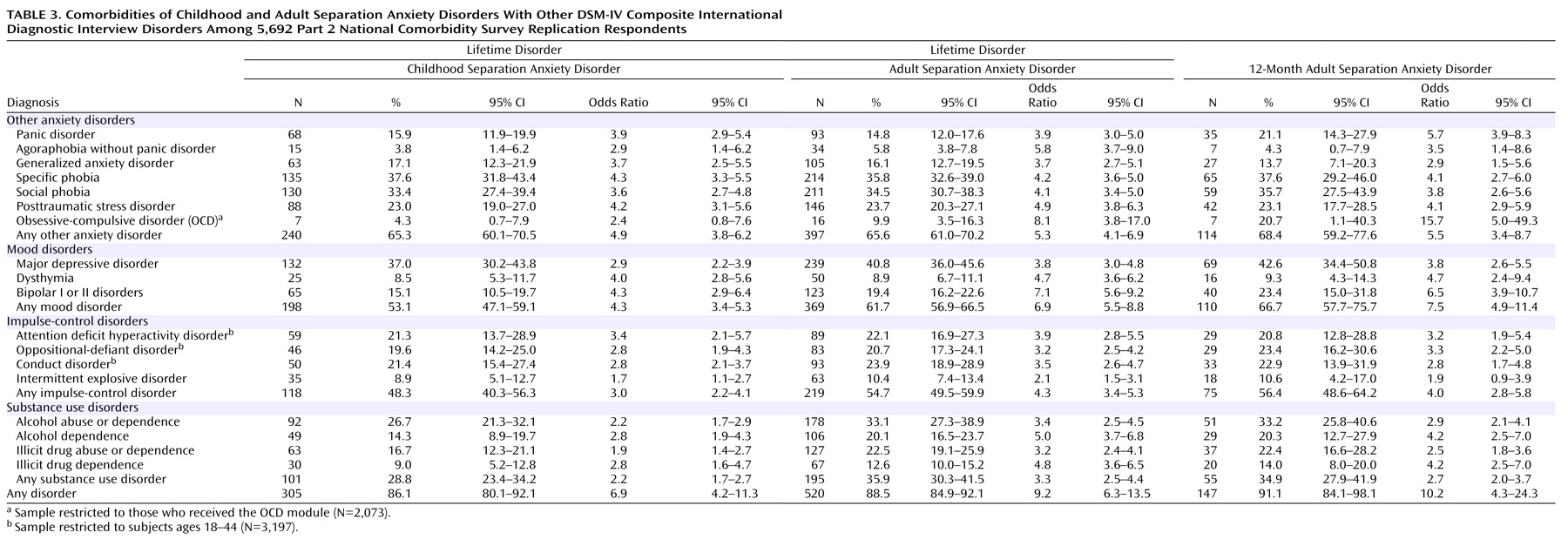

(26) . The finding that both estimated childhood and estimated adult separation anxiety disorder are strongly comorbid with many other DSM-IV disorders is consistent with a broader pattern of high comorbidity in the NCS-R

(28) and other epidemiological surveys

(29) . The finding that the odds ratios of estimated separation anxiety disorders with other anxiety disorders are no higher than with mood disorders and somewhat higher than with impulse-control and substance use disorders is consistent with the existence of a broad internalizing-externalizing distinction in the comorbidity of mental disorders

(28,

30 –32) . Methodological studies are needed to investigate whether comorbidities involving separation anxiety disorder are because of overlapping symptoms, imprecision of diagnostic criteria, or other methodological confounders. To the extent that such confounders can be ruled out, studies could profitably address whether these comorbidities are causal and, if so, whether early successful treatment of separation anxiety disorder in childhood and early adulthood would lower the rates of secondary adult disorders. A related question is whether adult separation anxiety disorder has any effect on the persistence or severity of other comorbid disorders. Because high comorbidity is generally found to be significantly associated with impairment

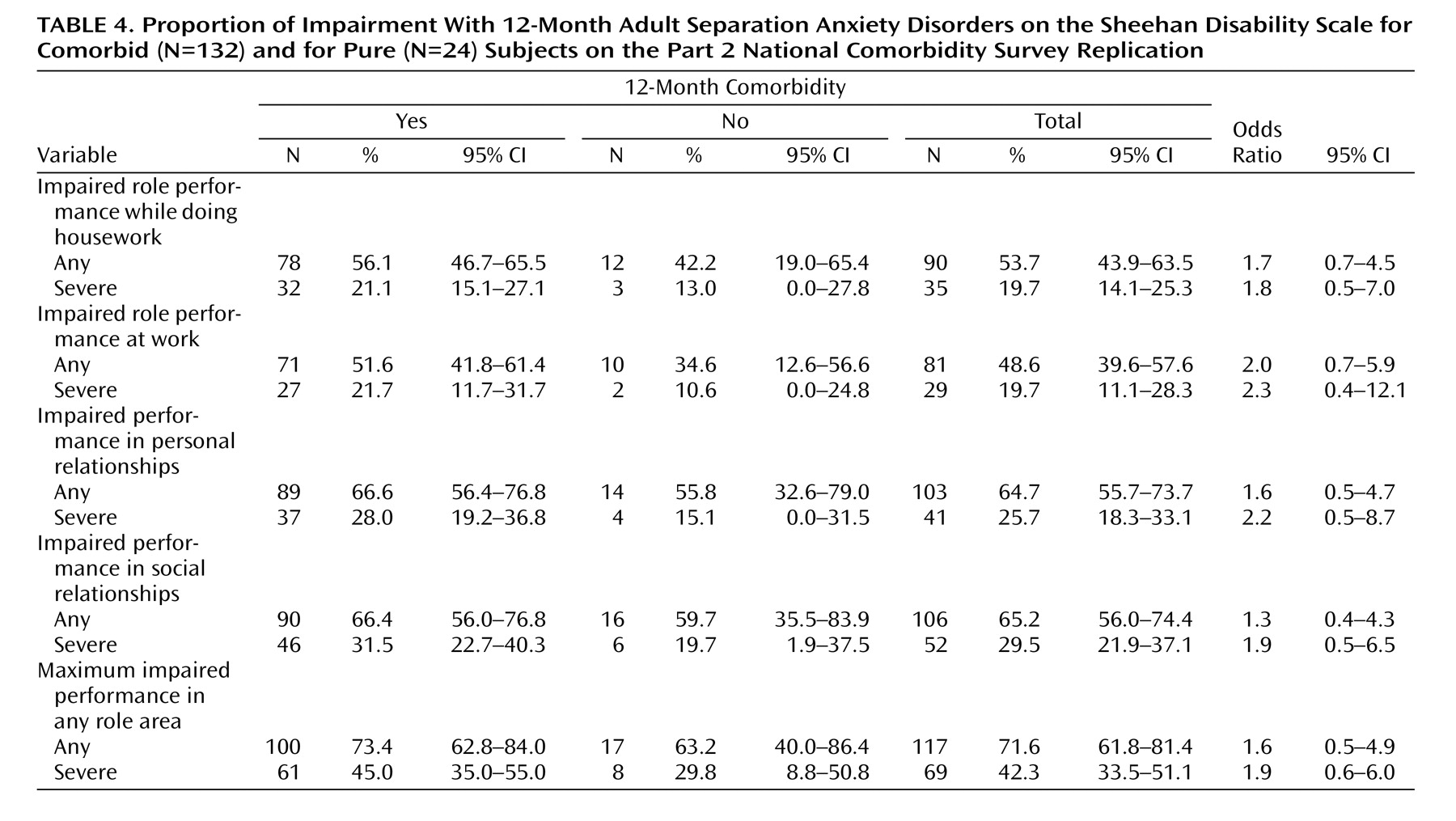

(28), it is not surprising that nearly half of the respondents estimated to have 12-month adult separation anxiety disorder experienced severe role impairment if they have comorbid conditions. The fact that more than one-fourth of the respondents with pure 12-month estimated separation anxiety disorder also reported severe role impairment, though, suggests that separation anxiety disorder can also be impairing in itself. Because this is the case, the question arises whether comorbid separation anxiety disorder accounts for some of the impairment previously attributed to other anxiety

(33 –

41), mood

(42 –

45), or substance use

(46) disorders. None of the many studies that estimated the societal costs of these conditions included separation anxiety disorder as a possible contributor to impairment. The finding that less than one-fourth of the children with estimated separation anxiety disorder receive treatment is consistent with research that documents substantial undertreatment of children with internalizing disorders

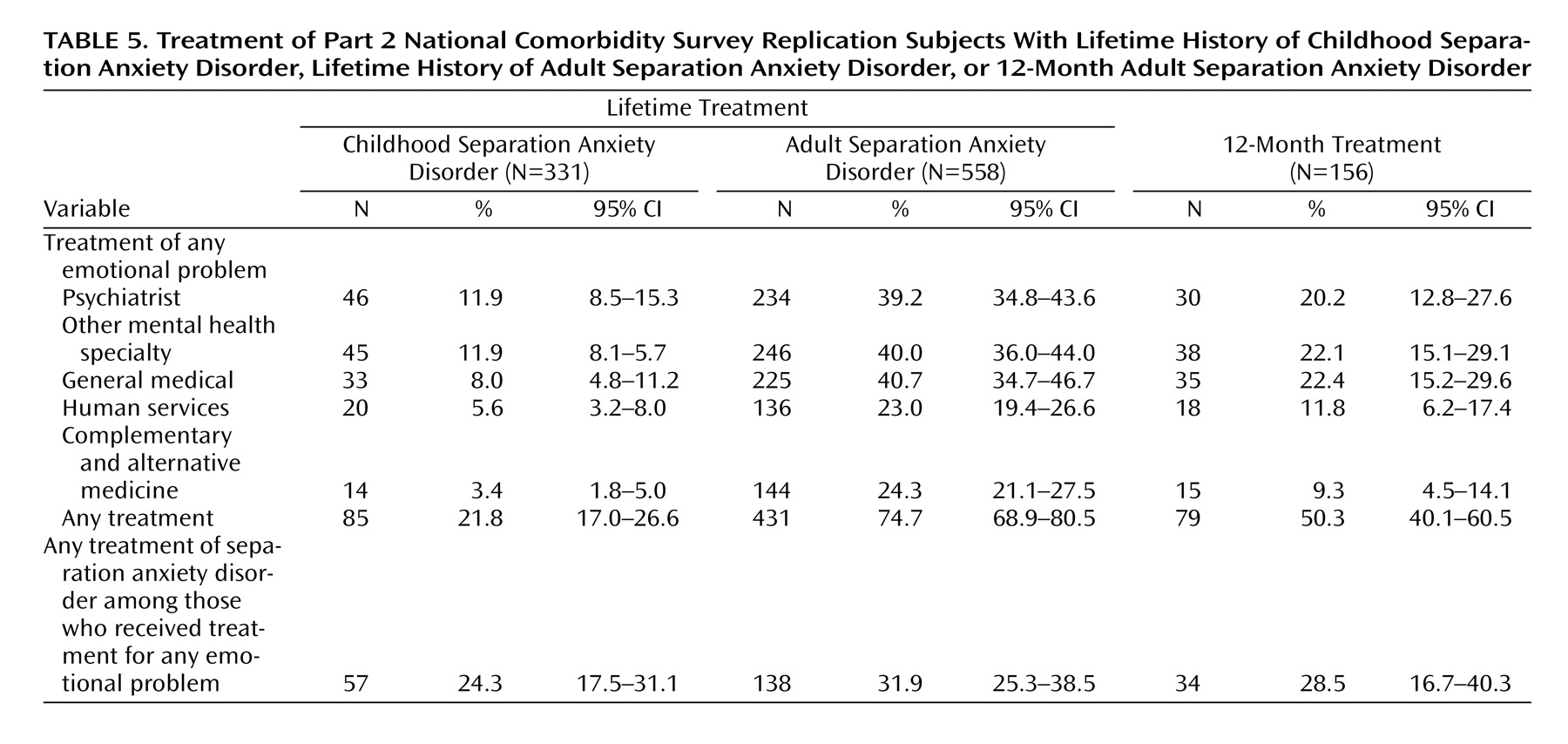

(47) . Treatment of adults with estimated separation anxiety disorder is dramatically higher (74.7%). However, the vast majority of patients reported that they were treated for comorbid conditions rather than for separation anxiety disorder. These results suggest that treatment providers often fail to recognize separation anxiety disorder in the context of other comorbid conditions. The absence of research on the treatment of adult separation anxiety disorder suggests that researchers have also largely overlooked this disorder. The NCS-R profile of nontrivial prevalence and impairment in the context of low treatment raises the question of whether detection and treatment of separation anxiety disorder in usual clinical practice are adequate. However, given that there was no clinical validation of the NCS-R separation anxiety disorder interview, it is possible that these data include false positives. Thus, before drawing firm conclusions or embarking on treatment studies, it would be important to carry out phenomenological and psychometric studies to refine the criteria for adult separation anxiety disorder and to confirm its prevalence and consequences. As noted in the introduction, current DSM criteria focus on the childhood disorder. It might be that the criteria could be usefully modified for adults, especially because the authors have evidence that most lifetime cases have first onset in adulthood. In considering the possible revision of diagnostic criteria for adults, it would be useful to focus on issues of symptom overlap and differential diagnosis with a number of the disorders included in this article, as well as with several other potentially related conditions (e.g., adjustment disorder, cluster C personality disorders). This is especially important in light of the fact that the vast majority of NCS-R respondents with 12-month estimated adult separation anxiety disorder (91.1%) were classified as meeting criteria for at least one other 12-month DSM-IV disorder. In further study, it would be important to explore the boundaries between normal response to loss of an attachment figure, separation anxiety as an adjustment reaction, and syndromal separation anxiety disorder. Given that infant separation anxiety is one of the most strongly conserved behaviors in evolution

(48 –

50) and given the importance of attachment relationships in adulthood, separation anxiety may be more easily elicited in adults than is commonly recognized and might be the norm under certain extreme life circumstances. Thus, it would make sense that diagnostic criteria take into consideration the possibility of expected reactions to extreme life stressors that create unusual but realistic interpersonal threats (e.g., living in a very dangerous neighborhood or a war zone, caring for a seriously ill child). In addition, as adult separation anxiety disorder becomes better understood, it would be valuable for the DSM criteria to provide assistance in distinguishing transient context-dependent separation anxiety symptoms or mild adaptive forms related to culturally accepted familial interdependence from a full-fledged pathological separation anxiety syndrome in need of treatment. The diagnosis of adjustment disorder with anxious mood is currently used in children when there are subthreshold, transient symptoms of separation anxiety. Consideration should be given as to when this should apply to adults as well. Once diagnostic criteria are clarified, it would be useful to carry out analytic epidemiological investigations to examine the many risk factors that might differ in predicting first onset in childhood versus adulthood and persistence of childhood cases into adulthood. Our superficial analysis of sociodemographic correlates already turned up potentially interesting specifications (e.g., stronger associations of socioeconomic status with adult than childhood estimated cases). A thorough investigation of similarities and differences across a wide range of risk factors would be enlightening. Comorbidity might also be a focus of risk factor analysis. For example, a growing literature documents that parental overprotection and control are risk factors for a wide range of childhood anxiety disorders

(51,

52) . It would be useful to investigate the extent to which these parenting styles account for the comorbidity of separation anxiety disorder with other anxiety and mood disorders, as well as the specific role of parental behavior in contributing to vulnerability to separation anxiety disorder. Such risk factor research could play a role in elaborating a conceptual model of separation anxiety disorder in relation to other internalizing disorders and might help elucidate factors that contribute to adult onset and/or persistence of syndromal or subthreshold separation anxiety disorder from childhood into adulthood. Such insights would inform the treatment development work needed to establish effective preventive and clinical interventions for this disorder.