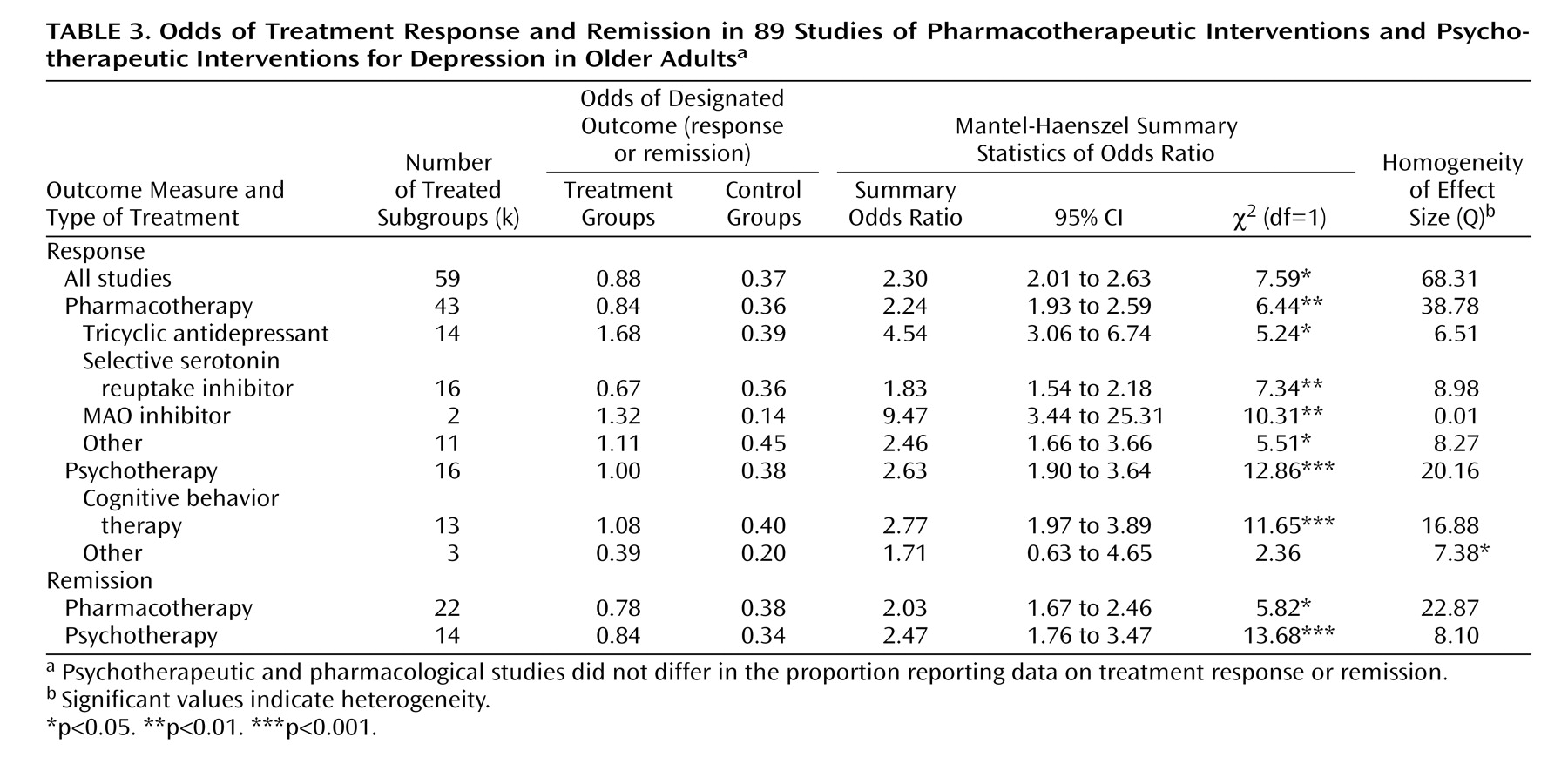

Treatment Responses

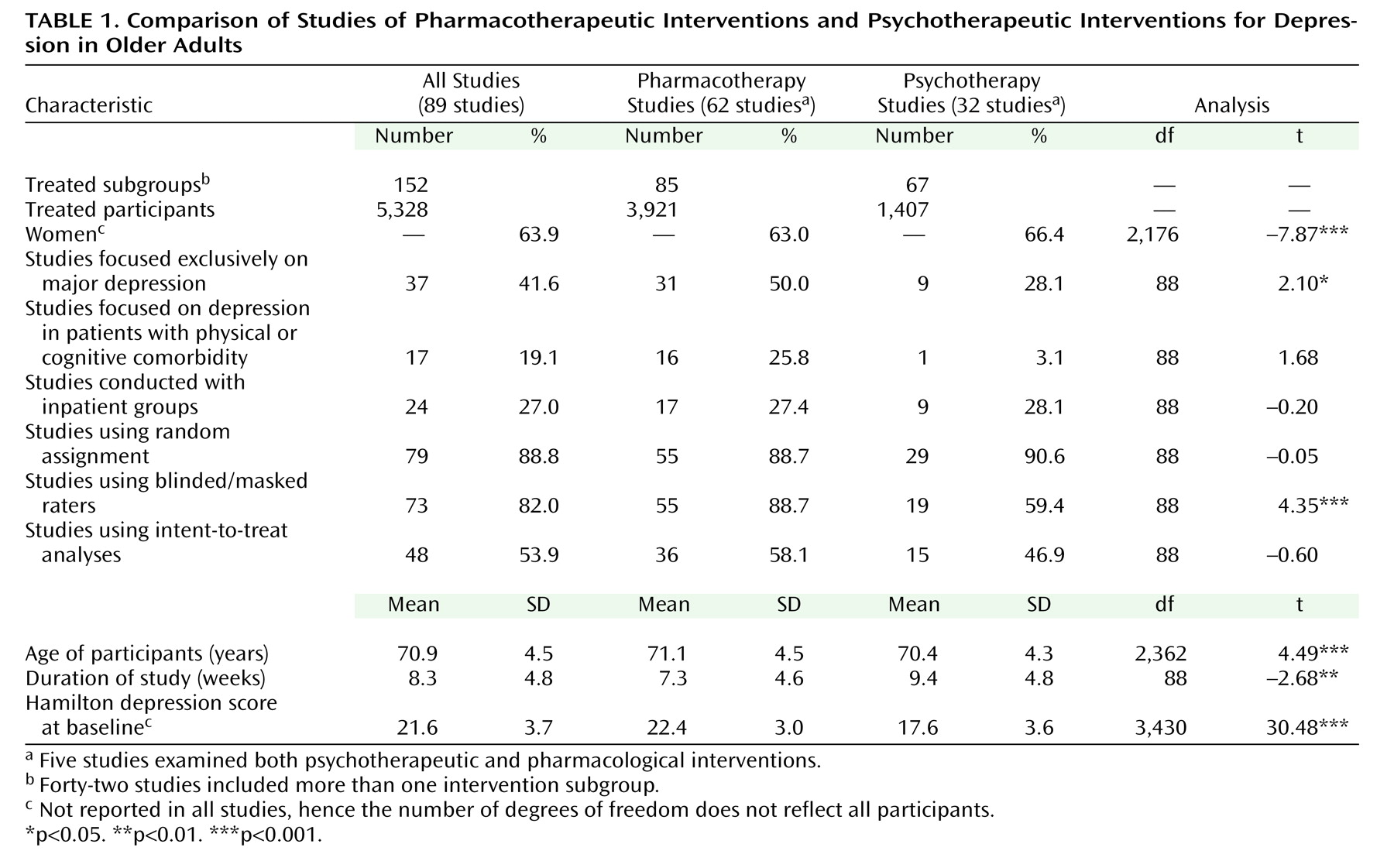

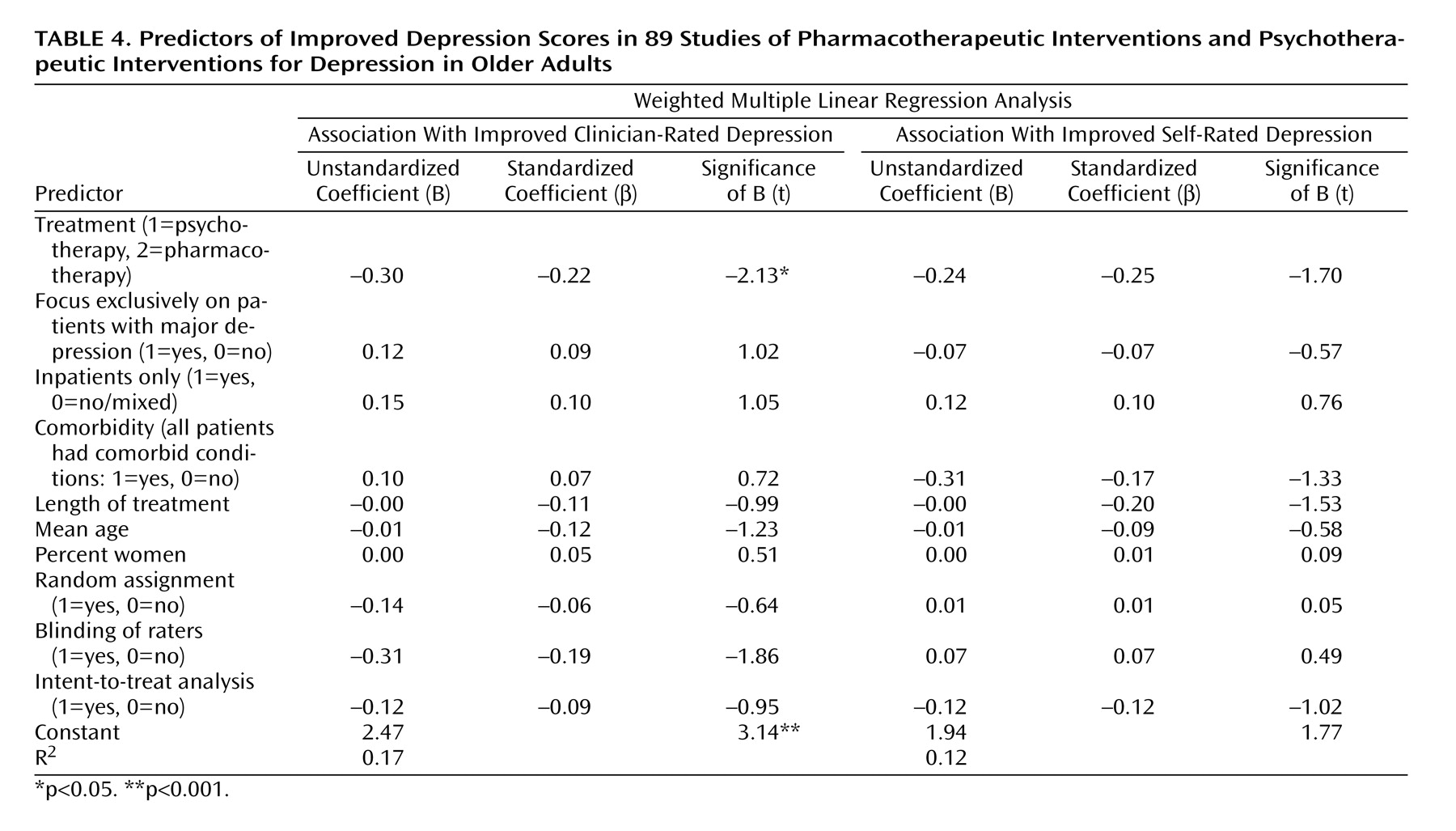

First, we computed the effects of pharmacotherapeutic and psychotherapeutic interventions. Separate analyses were computed for clinician-rated depression and self-rated depression (

Table 2 ). Negative d values indicate a stronger decline of depression in the intervention group than in the control group. For example, d=–1.00 would indicate a stronger improvement with treatment of 1.00 SD.

As shown in

Table 2, interventions produced an average improvement in clinician-rated depression of 0.80 SD units. For self-rated depression, the improvement was 0.76 SD units. When we apply Cohen’s guidelines

(50), the effect on clinician-rated depression may be described as large, whereas the effect on self-rated depression may be considered moderate. Rosenthal

(48) suggested the binomial effect size display as a tool for interpreting the practical importance of meta-analytic results. For clinician-rated depression, 68.6% of the members of the treatment groups and 31.4% of the control group members showed above-average improvement. The corresponding figures for self-rated depression are 67.8% (treatment) and 32.2% (control condition).

For clinician-rated depression, psychotherapeutic interventions showed larger effect sizes than pharmacotherapeutic interventions. This is shown by the absence of overlap of the confidence intervals and also by the binomial effect size display; 66.3% of the patients receiving pharmacotherapy and 72.4% of those receiving psychotherapy showed above-average improvement in clinician-rated depression. For self-rated depression, the two interventions yielded comparable effect sizes; 64.8% of the patients receiving pharmacotherapy and 69.2% of those in psychotherapy showed above-average improvements.

As pharmacological studies differ from psychotherapeutic studies in the use of an active placebo

(16), we further analyzed whether changes in the control group members differed between these treatment types. As indicated by the absence of overlap of the confidence intervals, we found stronger improvements in clinician-rated depression in the control groups in the medication trials (psychotherapy: k=23, d=–0.33, 95% CI=–0.53 to –0.13; medication: k=59, d=–0.91, CI=–1.23 to –0.60). When we used a different statistical method that did not control for nonspecific changes in control group members

(14), pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy showed similar effect sizes for clinician-rated depression (k=32, d=–1.75, CI=–1.96 to –1.53 versus k=69, d=–1.61, CI=–1.88 to –1.34) and self-rated depression (k=22, d=–0.80, CI=–1.09 to –0.52 versus k=48, d=–1.17, CI=–1.35 to –0.99). Thus, when we controlled for nonspecific changes in the control groups, we uncovered a slight advantage for psychotherapy on clinician-rated depression; failing to control for nonspecific changes obscured the difference between psychotherapy and medication.

Separate analyses of the five studies that included pharmacotherapeutic, psychotherapeutic, and control conditions showed no differences in effects for clinician-rated depression (pharmacotherapy: k=4, d=–0.54, CI=–1.00 to –0.09; psychotherapy: k=4, d=–0.41, CI=–0.82 to –0.00) and self-rated depression (k=3, d=–0.27, CI=–0.50 to –0.03 versus k=3, d=–0.19, CI=–0.41 to 0.04).

Next, we compared the effects of different medication classes and different psychotherapies. With respect to the pharmacotherapies, we were able to compare SSRIs with tricyclic antidepressants, MAOIs, and other drugs. The other drugs were acetyl- l -carnitine, an ACTH (4-9) analogue (Org 2766), alprazolam, bupropion, medifoxamine, fluvoxamine, iproniazid, l -sulpiride, methylphenidate, mianserin, minaprine, mirtazapine, nomifensine, trazodone, tryptophan, venlafaxine, viloxazine, and a combination of dihydroergocristine and l -5-hydroxytryptophan.

With regard to psychotherapy, we were able to compare cognitive behavior therapy against other psychotherapies. The other psychotherapies included eclectic psychotherapies, focused visual imagery group therapy (focusing the imagination on personal strengths and positive aspects of losses), interpersonal psychotherapy, psychodynamic therapy, and reminiscence. We also compared group therapy and individual psychotherapy. There were no significant differences in improvement of clinician-rated depression between the drug groups (

Table 2 ). However, the effect of cognitive behavior therapy on clinician-rated depression was greater than the effects of other forms of psychotherapy, SSRIs, other drugs, and all medications combined. With regard to change in self-rated depression, SSRIs were less effective than tricyclic antidepressants, MAOIs, other drugs, and both groups of psychotherapy. Given that only four studies of SSRIs were available, this result should be interpreted with caution.

Next, we investigated the effects of the clinical characteristics of the study groups. Analyses suggested that pharmacotherapy (k=39, d=–0.79, CI=–0.95 to –0.64, z=–10.01, p<0.001) and psychotherapy (k=16, d=–0.96, CI=–1.23 to –0.69, z=–6.87, p<0.001) were similarly effective in decreasing observer-rated depression in studies focused exclusively on major depression. However, in studies that also included patients with minor depression and/or dysthymia, the effect of psychotherapy was larger (k=19, d= –1.21, CI=–1.42 to –1.00, z=–11.48, p<0.001) than the effect of pharmacotherapy (k=38, d=–0.59, CI=–0.76 to –0.41, z= –6.40, p<0.001). The pattern of findings remained unchanged when we reran these analyses without the six studies focused on minor depression or dysthymia. The significant differences were confined to analyses of changes in clinician-rated depression; no differences were found for self-rated depression.

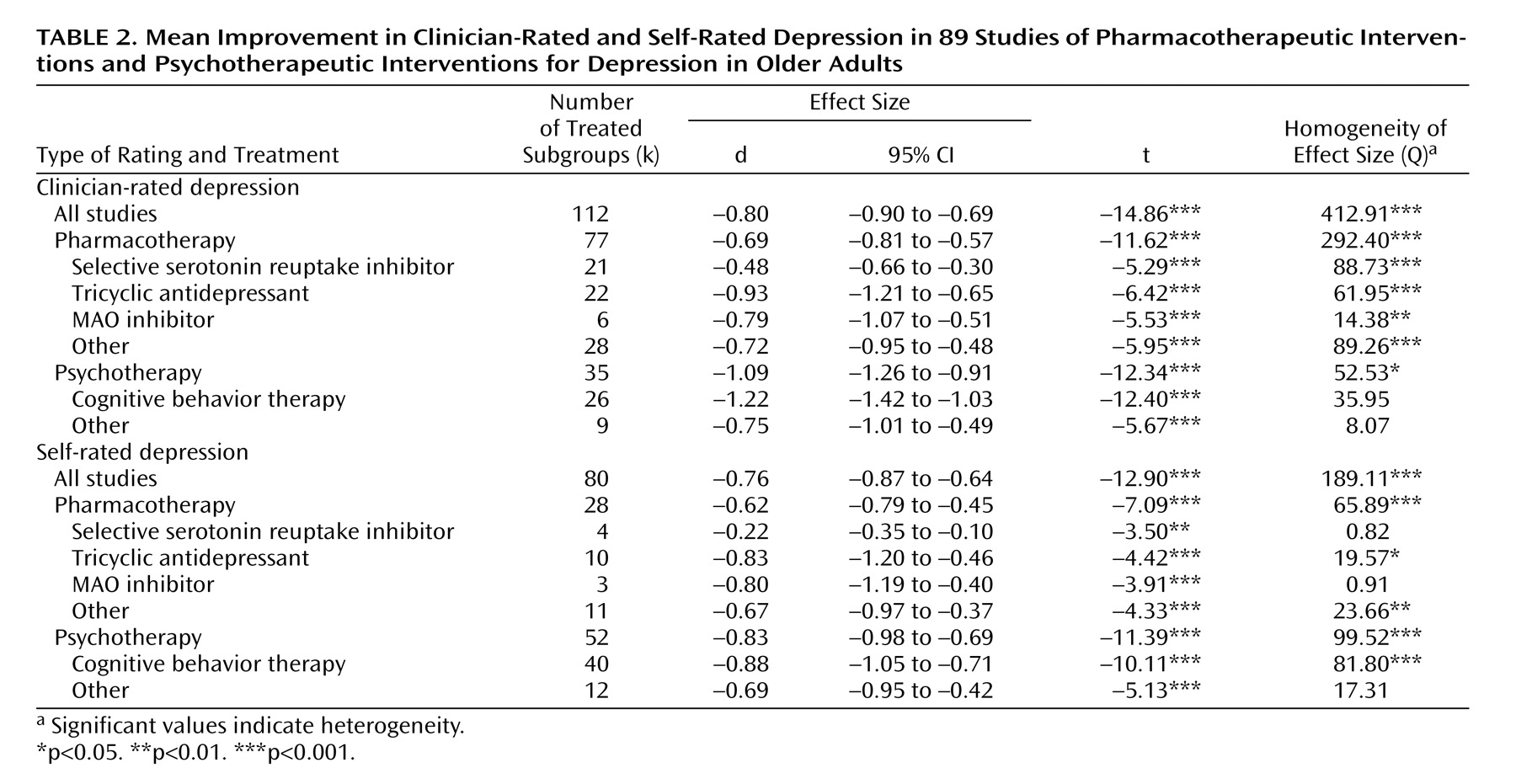

The reports on 41 studies (with 59 subgroups) included the proportion of responders. About 47% of patients in the treatment groups and about 27% of the control group members were responders. As shown in

Table 3, the relative odds of responding to the treatment condition (the quotient of the odds of responding divided by the odds of nonresponding) was 0.88, as compared to 0.37 in the control condition. Pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy yielded comparable odds, with overlapping 95% confidence intervals of the odds ratios.

Similar findings were observed when we analyzed the percentage of patients in remission. Again, the overlapping 95% confidence intervals indicate that there were no significant differences (

Table 3 ).