Scope and Nature of the Problem

According to DSM-IV-TR definitions and criteria, sexual dysfunction associated with medications or other substances is characterized by a disturbance in the processes that characterize the sexual response cycle (desire/arousal-excitement-orgasm-resolution) or by pain associated with sexual intercourse. The dysfunction results in marked distress or interpersonal difficulties, and it is fully explained by use of medication; the symptoms develop within 1 month of use of the medication, or the use of the medication is etiologically related to the disturbance.

Occasional reports of sexual dysfunction associated with use of monoamine oxidase inhibitors and tricyclic antidepressants began to appear during the 1960s and 1970s. With the arrival of newer antidepressants in the late 1980s and 1990s, reports of sexual side effects increased, notably with regard to use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). The reasons for the increased reporting are not entirely clear, although the trend is very likely multifactorial. Possible reasons include a much wider, more liberal use of the newer antidepressants for other conditions; pharmacotherapy of less severe depression that was previously more likely to be treated with psychotherapy; a more sophisticated approach to evaluation of side effects; a greater emphasis on patients’ quality of life; and even marketing competition among pharmaceutical companies. It is also possible that patients taking SSRIs simply experience more sexual dysfunction than patients taking tricyclic antidepressants

(1) and other antidepressants.

Since the introduction of SSRIs, sexual dysfunction associated with these agents has been reported in numerous case reports, case series, and open-label and double-blind studies; in recent years it has been frequently mentioned in efficacy studies and discussed in critical reviews (e.g., reference

2 ). The low incidence of sexual dysfunction reported in efficacy studies in the early 1990s was questionable, and since then some researchers have begun using more systematic ways of obtaining data on sexual dysfunction. Nevertheless, few industry-sponsored studies use validated instruments, and many use their own recently developed instruments. Approaches to obtaining such data vary and may be influenced by marketing strategies. Approaches used in recent efficacy reports have included use of “nonleading questions about adverse effects”

(3), reliance on “spontaneous notification and an open-ended inquiry of adverse events”

(4), and evaluating the presence of sexual dysfunction “at each visit via an investigator-conducted (blinded to study medication) interview”

(5) .

SSRIs may have a negative impact on any or all phases of the sexual cycle, causing decreased or no libido, impaired arousal, erectile dysfunction, and absent or delayed orgasm, but they are most commonly associated with delayed ejaculation and absent or delayed orgasm

(2) .

Our understanding of the neurobiology of sexual function is limited

(6) . Nevertheless, the involvement of various neurotransmitter systems

(7), such as inhibition of the ejaculatory reflex by serotonergic neurotransmission, and the impact serotonergic antidepressants have on these systems suggest that sexual dysfunction associated with use of SSRIs is in fact caused by them. Sexual dysfunction associated with SSRIs can present serious problems in the management of the various disorders treated with these medications; it can have an impact on treatment planning, recovery from the illness episode, quality of life, and adherence to the medication regimen, among other things.

Prevalence of SSRI-Associated Sexual Dysfunction

Estimates of sexual dysfunction associated with SSRIs vary, ranging from small percentages to more than 80%

(2) . The precise frequency is not known, and the issue is somewhat confounded by the fact that some studies report incidence (the number of new cases in a given population during a specified period) and some report prevalence (the number of existing cases in a given population during a specified period or at one time point).

Montgomery and colleagues

(8) pointed out numerous obstacles to establishing the exact prevalence of antidepressant-related sexual dysfunction. One is that data on the prevalence of sexual dysfunction in the general population (e.g., references

9,

10) are themselves scarce, which makes it difficult to establish a “normal” baseline. Second, patients with various mental disorders have an elevated risk of sexual dysfunction because of the effect of the illness on relationships and behavior

(11 –

13) . Third, human sexual behavior is subject to social and cultural influences, which may vary with time, place, ethnic group, social class, and so on. Fourth, data on sexual behavior are prone to underreporting; spontaneous reporting by patients and direct questioning by physicians have been reported to differ by as much as 60%. Fifth, the majority of studies on sexual dysfunction associated with antidepressants have methodological flaws, such as failure to use validated rating scales, a baseline assessment, a placebo group, randomization, or blinding. I would add that most studies do not take into account coexisting factors, such as comorbidity with other mental disorders (e.g., major depression and anxiety disorders), comorbid substance abuse, comorbid physical illness, and treatment with other medications that may cause sexual dysfunction (e.g., cardiovascular medications).

Studies by Montejo et al.

(14) and Clayton et al.

(15) illustrate the difficulty in estimating the incidence and prevalence of sexual dysfunction associated with SSRIs: the differences, for various SSRIs, between the incidence of sexual dysfunction in the first study and the prevalence in the second study were 73% versus about 40% for citalopram, 58% versus 36% for fluoxetine, 71% versus 43% for paroxetine, and 63% versus 40% for sertraline. In another study

(16), the prevalences of sexual dysfunction with antidepressants (SSRIs and others) in the United Kingdom and in France were estimated at 39% and 27%, respectively.

A realistic estimate of the incidence of SSRI-associated sexual dysfunction would probably lie between 30% and 50%. Montgomery and colleagues

(8) did not find robust enough evidence to support claims for the differences in the incidence of drug-induced sexual dysfunctions between available antidepressants.

Sexual Dysfunction and Mental and Physical Illness

The lack or decrease of sexual desire, or libido, has long been a known part of depressive symptomatology

(11,

12), and estimates of sexual dysfunction in patients with unipolar depression range from 25% to 47%

(17) . In one small study of patients with major depression

(18), reduced levels of arousal were more common in both men and women (40%–50%) than difficulties with ejaculation or orgasm (15%–20%). However, sexual dysfunction has also been described in other mental disorders, such as posttraumatic stress disorder

(19) and other anxiety disorders

(13,

20) . Recreational drugs, such as nicotine

(21), alcohol, cocaine, and opioids, could also have a negative impact on sexual functioning

(22) .

Clinicians should be aware that delayed ejaculation and orgasm, symptoms most frequently associated with SSRIs, are not usually associated with depression itself, whereas decreased sexual desire is. Also important to bear in mind is that sexual functioning fluctuates in ordinary life and that sexual desire and expectations evolve over the life cycle

(23) . Sexual desire is also influenced by various psychological factors, such as joy, sorrow, mutual affection, disagreement, and so on

(23) .

Sexual dysfunction is associated with diseases such as diabetes mellitus and hypertension (mostly erectile dysfunction) and with various medications, including antihypertensives and hormonal preparations such as antiandrogens and gonadotropin-releasing-hormone agonists. Some might wonder whether, given that so many other disorders and medications are associated with sexual dysfunction, SSRIs alone can be causative. In fact, sexual dysfunction has been found to occur in healthy volunteers after administration of fluvoxamine

(24), and numerous studies by Waldinger and colleagues (e.g., reference

25 ) have demonstrated delayed ejaculation after administration of SSRIs in humans and rats.

Clinical Evaluation

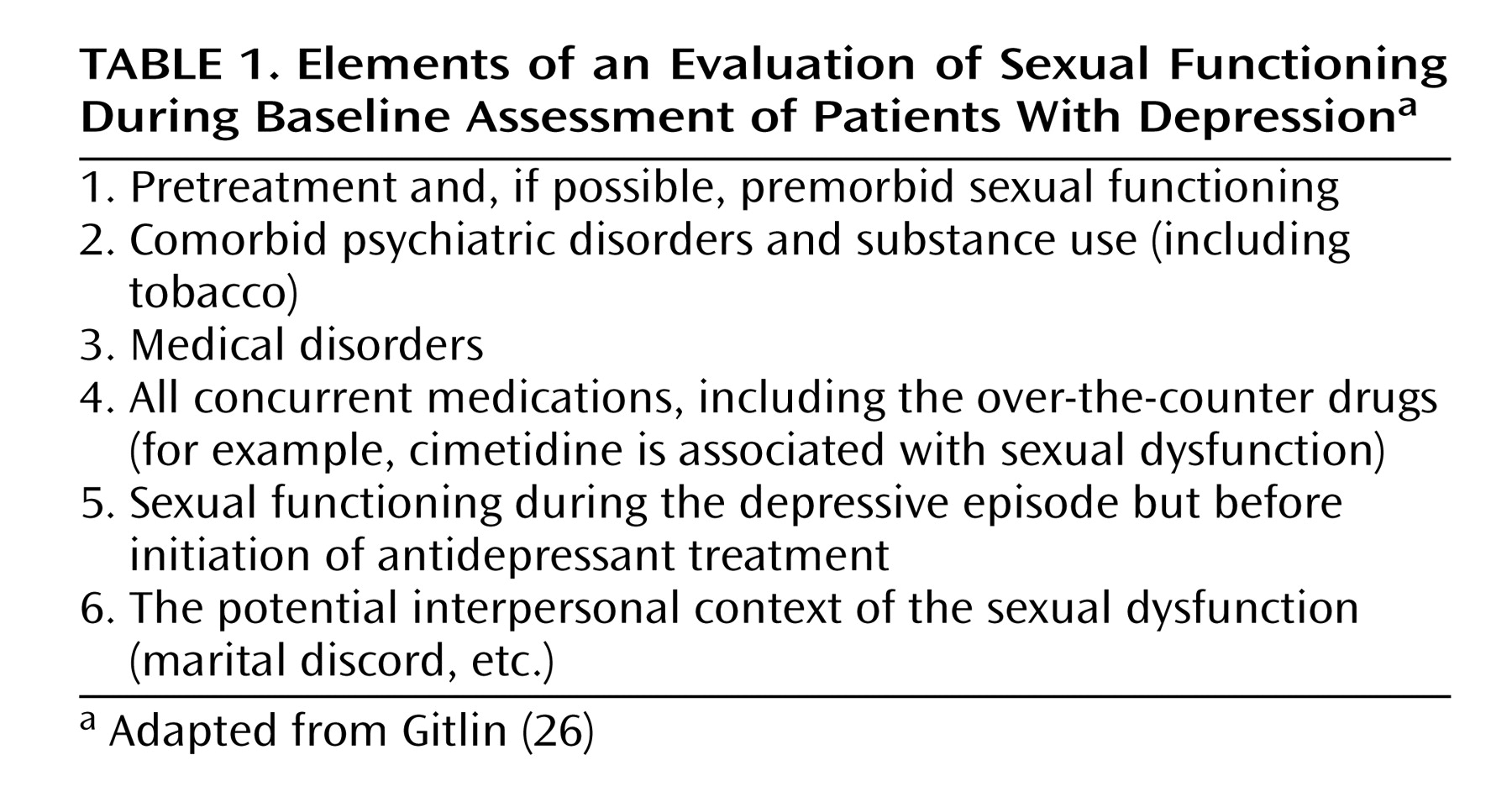

Sexual dysfunction associated with SSRIs and other medications is clearly a complicated problem. How should clinicians deal with the potential for sexual dysfunction as a sequela of treatment? Proper management starts during the initial contact and evaluation, before any medication is prescribed. Considering the numerous possible confounding factors, a baseline evaluation of sexual functioning is essential. One cannot rely solely on the patient’s memory and recall after a few weeks of treatment (“I don’t think I suffered from this before”). A thorough inquiry into sexual functioning during the evaluation provides invaluable information. Gitlin

(26) suggested systematically evaluating six areas as part of the general baseline assessment (

Table 1 ).

The evaluation of premorbid and pretreatment sexual functioning should not be limited to general questions such as “How is your sex life?” The patient should be asked about the phases of sexual function (libido, arousal, orgasm), sexual fantasies, frequency of intercourse and/or masturbation, and satisfaction with overall sexual functioning. Clinicians might consider using some of the established questionnaires, both for obtaining a quantified baseline and as an ongoing evaluation tool. Examples of validated instruments include the Arizona Sexual Experience Scale

(27) and the Changes in Sexual Functioning Questionnaire

(28) .

The pretreatment clinical evaluation should include a discussion about the possibility of a sexual dysfunction resulting from the selected antidepressant and possible management strategies. The patient should be asked to report any sexual dysfunction that occurs during treatment.

Management Strategies

Given the scarcity of evidence-based treatments, the management of sexual dysfunction is still an art rather than a science. Even a seemingly clear-cut case of medication-associated sexual dysfunction should not be treated in a vacuum or in a strictly biological sense. The overall treatment plan should always take into consideration psychological factors and normal fluctuation of sexual functioning. It should also promote a healthy life style, recommending, for example, weight reduction, exercise, smoking cessation, and treatment for substance use problems. A healthy life style can be helpful in a variety of ways, including by enhancing self-image, sense of well-being, overall health, and the health of the physiological systems related to the sexual response cycle. Some patients may have pretreatment life-style-related sexual dysfunctions in addition to an SSRI-associated dysfunction, such as those caused by chronic use of substances, including tobacco and alcohol. Reducing the severity of a life-style-related dysfunction may render the SSRI-related dysfunction more manageable.

Several additional strategies for which we lack any good empirical evidence may nonetheless be useful for individual patients. Cognitive behavior therapy focused on sexual dysfunction may help the patient cope with the dysfunction, reduce symptom severity, or help prevent potential symptom worsening due more to the presence of the sexual dysfunction than to the effect of the SSRI. Educating the patient about masturbation, mutual masturbation, use of vibrators, and use of fantasies can be helpful.

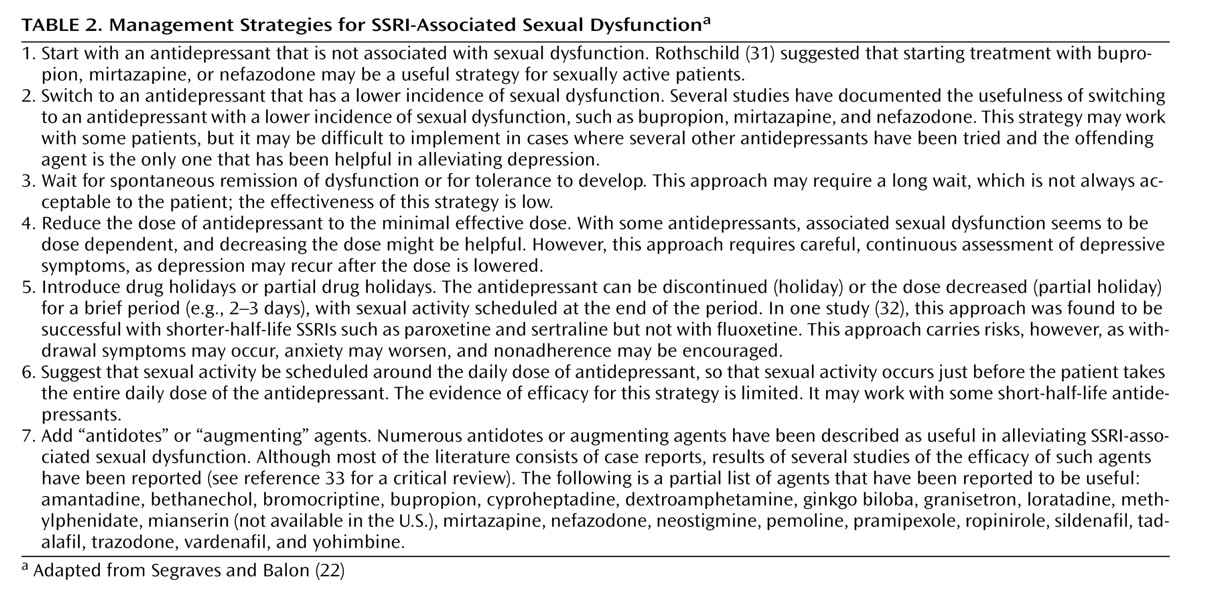

Numerous publications, including case reports, case series, study reports, review articles (e.g., references

28,

29), book chapters

(30), and books

(22), recommend basic management strategies for SSRI-associated sexual dysfunction. These strategies are summarized in

Table 2 .

Like the prevalence studies, the treatment studies of SSRI-associated sexual dysfunction suffer from methodological problems, among them unclear dosing of “antidotes,” lack of randomization, uncertain minimum duration of treatment with an antidote, lack of placebo, lack of a gold standard, lack of well-defined outcomes, and unsatisfactory reporting of dropouts.

Taylor and colleagues

(33) analyzed 15 trials with a total of 904 subjects. They reported that in one trial, switching to nefazodone was less likely to induce sexual dysfunction than restarting sertraline (relative risk=0.34, 95% confidence interval [CI]=0.15–0.6). They also reported that in a meta-analysis of two trials, adding sildenafil resulted in less sexual dysfunction (compared with placebo) at endpoint (weighted mean difference=19.36, 95% CI=15.00–23.72). In one trial, adding bupropion led to improved scores, compared with placebo, on the desire-frequency subscale of the Changes in Sexual Functioning Questionnaire (weighted mean difference=0.88, 95% CI=0.21–1.55), and in another, adding tadalafil was associated with greater improvement in erectile function compared with placebo (weighted mean difference=8.10, 95% CI=4.62–11.68). However, Taylor et al. did not find significant improvement in trials comparing bupropion and placebo, buspirone and placebo, granisetron and placebo, amantadine and placebo, amantadine and buspirone, olanzapine and placebo, mirtazapine and placebo, yohimbine and placebo, olanzapine and mirtazapine, olanzapine and yohimbine, mirtazapine and yohimbine, ginkgo biloba and placebo, and ephedrine and placebo (some reports combined more than one comparison). Their review did not include the most recent trial by Fava and colleagues

(34), in which sildenafil was found to be well tolerated and to significantly improve erectile function and overall sexual satisfaction in men with SSRI-associated erectile dysfunction.

Evidence from randomized trials on the efficacy of other strategies listed in

Table 2 is lacking. The only evidence-based or proven approaches to management of SSRI-associated sexual dysfunction seem to be, for erectile dysfunction, the addition of phosphodiesterase-5 (PDE-5) inhibitors such as sildenafil and tadalafil; for decreased libido, possibly adding or switching to bupropion; and for overall sexual dysfunction, switching to nefazodone.

Summary and Recommendations

Sexual dysfunction resulting from treatment with an SSRI requires a careful and sophisticated management approach. The diagnosis of SSRI-associated sexual dysfunction is difficult to make without a thorough baseline assessment and periodic clinical monitoring of sexual functioning. Adding a PDE-5 inhibitor (after a careful medical and medication history) in cases of erectile dysfunction and adding bupropion in cases of decreased libido seem to be the best-supported strategies, along with switching to certain non-SSRI antidepressants. Other management strategies, such as lowering the dose, drug holidays, and so on, may nevertheless be used clinically, with careful consideration of the type of sexual dysfunction, the clinical situation, comorbid conditions, and concurrent medications. Addressing the underlying pathophysiology may serve as a guiding principle for deciding on a management strategy for certain sexual dysfunctions—for example, using a dopaminergic agent when libido is decreased. Additional management strategies, such as sex therapy and promotion of a healthy life style, may be useful.

How would one manage the cases described at the beginning of this article?

In the case of the woman with dysthymia, switching to or adding bupropion would probably be the most prudent approach. If switching, however, close monitoring is needed because a relapse of her dysthymia is possible. Additional possibilities might include the use of cognitive behavior therapy focused on sexual dysfunction and educating the patient about mutual masturbation and use of vibrators, although, as noted, we lack good evidence for these strategies.

In the case of the man with obsessive-compulsive disorder, adding sildenafil or tadalafil would be useful. Here, too, inquiring carefully about sex, fantasies, and habits, or educating the patient about techniques such as mutual masturbation may be useful, but evidence for these additional strategies is largely lacking.