A spectrum of affective illness follows childbirth, from the common, mild, and transient baby blues to postpartum (puerperal) psychosis, which can be classed among the most severe episodes of illness seen in clinical practice. The postpartum period is clearly a time of increased risk for episodes of affective psychosis, particularly for bipolar women

(1,

2) . We previously reported compelling evidence for the familial clustering of postpartum episodes in women with bipolar disorder: episodes of postpartum psychosis occurred in 74% of parous bipolar women who had a family history of puerperal psychosis in a first-degree relative but in only 30% of women with bipolar disorder with no such family history

(3) .

Postpartum (postnatal) depression is perhaps the most common psychiatric disorder following childbirth and is a term used to cover a wide variety of episodes of illness that occur in the months following delivery. Prevalence estimates vary widely according to the definition of postpartum onset (e.g., 4 weeks, 6 weeks, or 6 months) and the methods used to establish postpartum depression (e.g., clinical interview versus self-report). From the results of a large number of studies, however, meta-analysis has estimated the prevalence rate of nonpsychotic postpartum depression to be 13%

(4) .

Postpartum depression is a significant mental health issue, with serious consequences for the mother, infant, and family. The term has undoubtedly been useful in the fight for clinical services for women who become ill at this time. Despite its clinical and political importance, however, there have been a number of challenges to the scientific validity of the concept of postpartum depression, including the suggestion that postpartum depression is no different in nature to episodes of depression that occur at other times

(5) . This has led to the idea that childbirth is acting as a nonspecific stressor rather than as a specific trigger for illness onset at this time.

However, while there is no evidence to support postpartum depression as a separate nosological entity, evidence that childbirth is a specific trigger of depressive illness in a proportion of women has been presented. Cooper and Murray

(6), in a study that has yet to be replicated, found that relative to women whose postpartum depression was a recurrence of a previous nonpostpartum depressive disorder, women whose postpartum depressive episode was their first depressive experience were at

greater risk for subsequent postpartum depressive episodes but at

lower risk of subsequent nonpostpartum depression. Second, in a paradigm that simulated the hormonal fluctuations of pregnancy and childbirth, Bloch and colleagues

(7) found that women with a history of postpartum depression displayed significantly greater mood sensitivity to changes in gonadal steroid levels than comparison subjects. Third, Treloar and colleagues

(8) suggested that different genetic factors may play a role in postpartum and nonpostpartum depression. Although the scientific status of postpartum depression as a specific nosological category is weak, a number of lines of evidence have suggested that childbirth can act as a specific trigger of depressive episodes in some women and that a subgroup of women with major depression are vulnerable to a postpartum trigger, be it biological or psychosocial in nature.

The aims of the current study were 1) to examine further the concept of a specific childbirth-related trigger, 2) to determine whether vulnerability to the postpartum triggering of depressive episodes aggregates in families, and 3) to assess how this aggregation varies with the definition of postpartum depression.

Method

Subjects

An international multicenter study of sibling pairs with unipolar depression (the Depression Network [DeNt] study) recruited families multiply affected with recurrent major depression for a linkage genome screen

(9,

10) . Participants were identified through the systematic screening of community mental health teams and nonsystematically via advertisements in local general practitioner offices and local media as well as contact with patient support organizations. The study received all necessary multi-region and local ethical approval.

Patients were included if they 1) met DSM-IV and ICD-10 criteria for major recurrent depression; 2) were above 18 years of age, 3) were of U.K./Eire white ethnicity (due to the fact that they were recruited for molecular genetic studies); and 4) had at least one full sibling also meeting all of the inclusion criteria.

Subjects were excluded if they were: 1) adopted; 2) a monozygotic twin of a proband; 3) had ever had psychotic symptoms that were mood incongruent or were prominent at a time when there was no evidence of mood disturbance; 4) had a lifetime diagnosis of intravenous drug dependency; 5) had depression only as a result of alcohol or substance dependence or secondary to medical illness or medication; or 6) had a first- or second-degree relative with a clear diagnosis of bipolar affective disorder, schizophrenia, schizotypal disorder, persistent delusional disorder, acute and transient psychotic disorders, or schizoaffective disorder.

Assessment

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants who were interviewed using the Schedules for Clinical Assessment in Neuropsychiatry. Psychiatric/general practice case notes were also reviewed, and detailed information was collected on the relationship of episodes of illness to childbirth. Each pregnancy was assessed according to the following criteria: 1) narrowly defined postpartum depression (onset of DSM-IV major depression within 4 weeks of delivery), and 2) broadly defined postpartum depression (onset of DSM-IV major depression within 6 months of delivery). All available information was collated into a structured written vignette, and consensus ratings and best-estimate lifetime diagnoses including postpartum episodes were made by at least two members of the research team blind to each other’s ratings. All interviews and consensus ratings were conducted by trained psychiatrists or psychologists with weekly consensus meetings of the research team to prevent rater drift. Interrater reliability was formally assessed using joint ratings of 20 cases with a range of mood disorder diagnoses. Mean overall kappa statistics of 0.85 and 0.83 were obtained for DSM-IV and ICD-10 diagnoses, respectively. Other key clinical variables had mean kappa statistics and intraclass correlations coefficients (ICCs) that ranged from 0.81–0.99 and 0.85–0.97, respectively.

Of the 240 patients from the 120 sibling pairs (one pair per family) recruited at the Birmingham site, 135 were parous women. There were 60 female/female pairs, 52 male/female pairs, and eight male/male pairs. Of the 60 female/female pairs, there were 45 where both sisters were parous, and these pairs were the main focus of our analyses.

Statistical Analysis

The association of lifetime and first pregnancy postpartum depression status between pairs of parous sisters was assessed by tetrachoric correlation coefficient

(11) .

Results

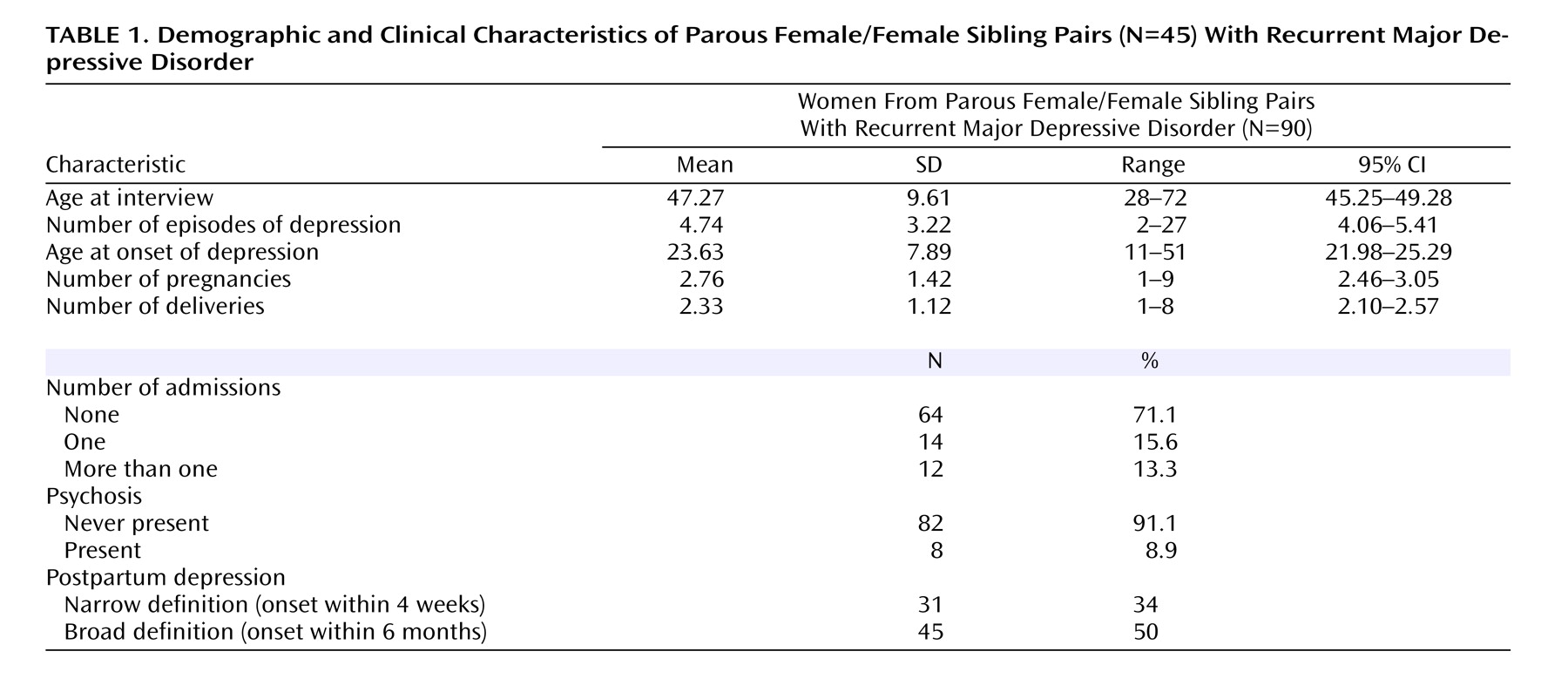

The mean age at onset of depression for the 90 parous women (45 sibling pairs) was 24 years (SD=7.9), and the mean number of depressive episodes was 4.7 (SD=3.2) (

Table 1 ). Twenty-six women (29%) had been admitted to a psychiatric unit for depression at some stage during their lives. Eight women (9%) had experienced psychotic symptoms during a depressive episode. The mean number of pregnancies was 2.8 (SD=1.4), and the mean number of deliveries was 2.3 (SD=1.1).

Thirty-one (34%) of the women had experienced at least one postpartum depressive episode with onset occurring within 4 weeks of delivery, and 45 (50%) had experienced postpartum depression within 6 months. Of the 210 deliveries to the 90 women, 18% were followed by postpartum depression with onset occurring within 4 weeks; 26% experienced onset within 6 months of delivery.

Concordance Between Sibling Pairs for Postpartum Episodes

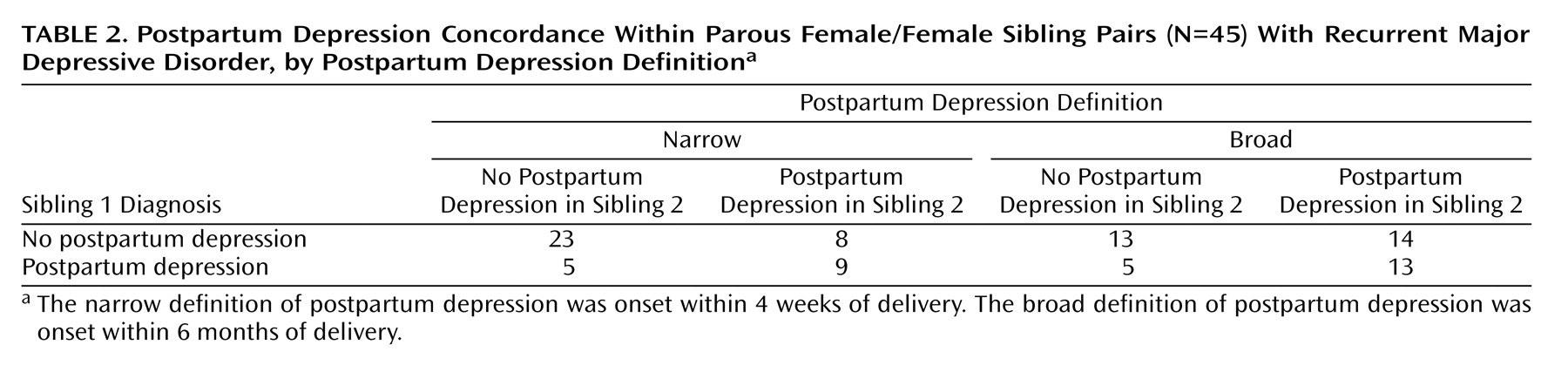

As seen in

Table 2, for narrowly defined postpartum depression, 32 were concordant and 13 were discordant (tetrachoric correlation coefficient=0.55, 95% CI=0.11–0.83; p<0.02). Employing the broad definition of postpartum depression, 26 of the 45 sibling pairs were concordant and 19 were discordant (tetrachoric correlation coefficient=0.24, 95% CI=0.00–0.63; p=0.28).

Women differed in the number of children they had had, and therefore in the opportunity to experience an episode of postpartum depression. In order to take account of these differences, and to ensure that the familiality demonstrated was not due merely to familial influences on parity, we also analyzed the concordance of postpartum episodes following the women’s first delivery only. This analysis supported the familiality of narrowly defined postpartum depression (tetrachoric correlation coefficient=0.62, 95% CI= 0.16–0.88; p=0.01).

Variation in the Definition of Postpartum Onset

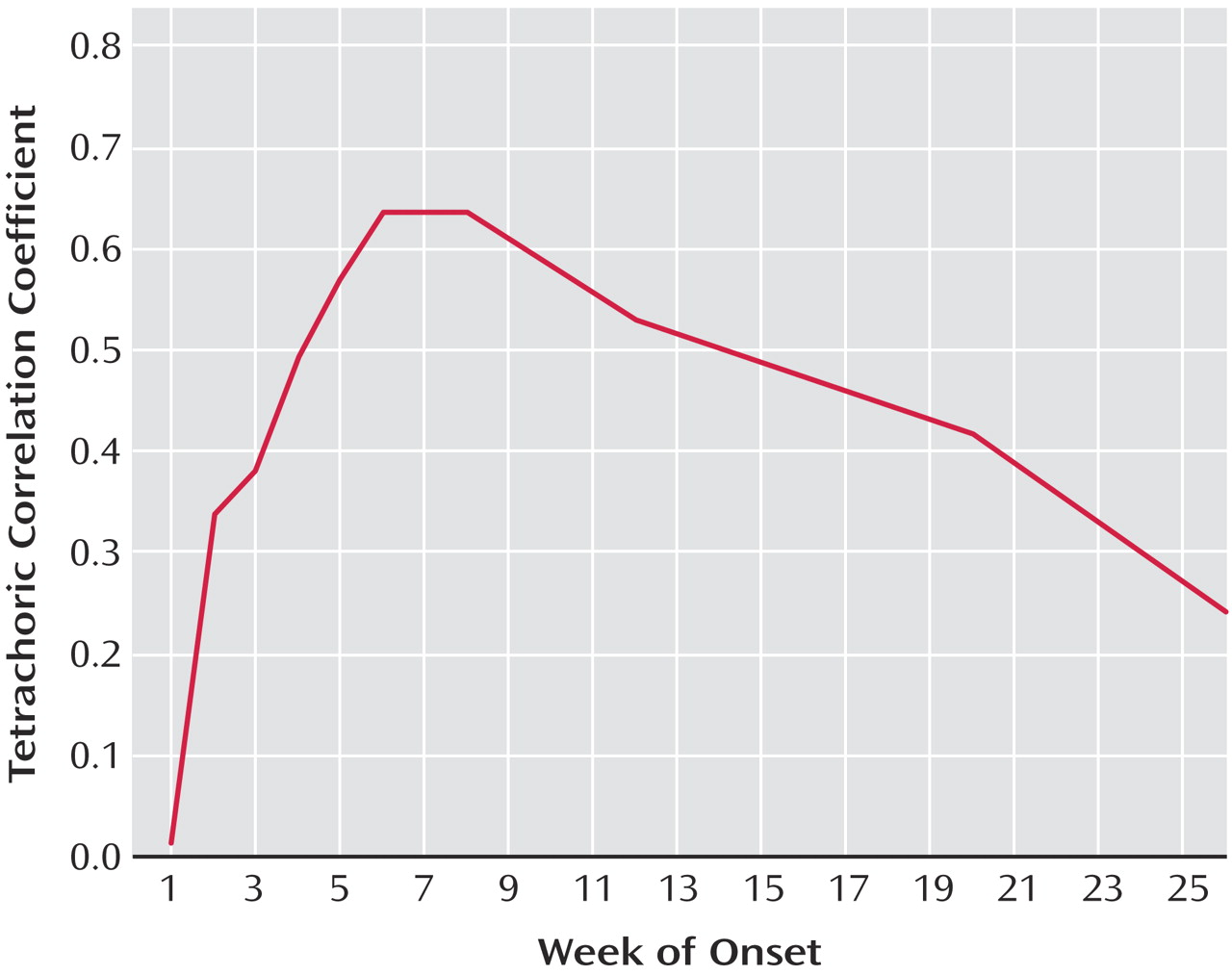

Given the difference in results between the narrow and broad definitions employed here, we were interested in seeing how varying the definition of postpartum onset more widely influenced the evidence for familiality.

Figure 1 demonstrates that in varying the definition between 1 week and 26 weeks, the evidence for familiality maximized for a definition of postpartum onset of between 6 and 8 weeks.

Risk of Postpartum Depression per Delivery

While the tetrachoric correlation coefficients reported here demonstrate the familiality of liability to narrowly defined postpartum depression, it may be of clinical benefit to consider our results in terms of the risk of postpartum episodes per delivery.

Of the 90 parous women, 31 had a sister with a history of narrowly defined postpartum depression, and 29% of all deliveries (42% of first deliveries) to these women were followed by an episode of postpartum depression. Of the 59 women whose sister had not suffered an episode of narrowly defined postpartum depression, only 12% of all deliveries (15% of first deliveries) were followed by an episode of postpartum depression.

Discussion

This study provides evidence for the familiality of postpartum depression in a well-characterized group of siblings with recurrent major depression. It adds to the evidence suggesting that a subgroup of women with major depression have a specific vulnerability to the triggering of episodes by childbirth. In addition, we have demonstrated that familiality is dependent on the definition of postpartum episode. The evidence for familial aggregation was significant for narrowly defined postpartum depression (onset within 4 weeks of delivery, corresponding to the postpartum onset specifier in DSM-IV) but not for a broader definition (onset within 6 months of delivery) that is perhaps more typical of the way the diagnosis is used as a lay term and applied in clinical practice. The evidence for familiality maximized with a definition of postpartum onset of 6–8 weeks.

Our results provide further support for the well-established finding that a history of major depression is an important risk factor for depression in the postpartum period. Of our patients diagnosed with recurrent major depression, narrowly defined postpartum depression followed 18% of deliveries, and 26% of deliveries were followed by an episode of depression within 6 months. Comparisons with previous studies examining rates of postpartum depression in the general population are not straightforward because of very different methodologies and definitions of episodes of illness. However, the rates we report here are higher than those described in the meta-analysis of O’Hara & Swain

(4) and, furthermore, are likely to represent more severe episodes than those picked up by questionnaire measures alone

(4) .

That

family history is an important risk factor for major depression is well established: the influence of family history on vulnerability to postpartum depression is much more controversial. Indeed, the meta-analysis of O’Hara and Swain did not support family history as a risk factor for depressive episodes

(4) . What then, could account for the differences between this and previous studies? It is likely that there are substantial methodological differences, including the definition of postpartum depression, the methods used to assess postpartum depression, and, finally, the assessment of family history. In this study, episodes of depression (including postpartum depression) and family history were assessed by direct interview of participants. Consensus diagnoses were made by at least two members of the research team, and our study group consisted only of patients with recurrent major depression. In contrast, previous studies relying on questionnaire measures may have resulted in a more heterogeneous group including single episode depressive disorder, minor depressive disorder, and, with regard to onset, a wide definition of postpartum episode. In addition, we were asking a related, but slightly different, question to previous studies. While the question previously regarded whether a family history of depression increases risk for an episode of depression following childbirth, we asked whether a family history of

postpartum episodes influences vulnerability to postpartum episodes in women from families multiply affected with recurrent major depression.

Implications

Clinical Practice

Women with recurrent major depression with a family history of narrowly defined postpartum episodes are much more likely to experience a depressive episode following childbirth (42% of first deliveries) than those with no such family history (15% of first deliveries). Questions about postnatal episodes in first-degree relatives will therefore enable a more individualized risk assessment to be made for women with a history of major depression contemplating pregnancy.

Nosology

The definitions of postpartum onset in the classification systems are essentially arbitrary. Despite wide confidence intervals for the tetrachoric correlations under the various definitions of postpartum onset, our study suggests that neither a very broad or restrictively narrow definition of postpartum onset is appropriate. Our results provide some indication that the 4-week postpartum onset specifier in DSM-IV may be too narrow, since familiality maximized with a 6–8 week definition of postpartum onset.

Research

Postpartum depression remains an underresearched area, particularly with regard to studies focusing on the etiology of episodes of depression occurring at this time. The results reported here suggest that a focus on postpartum triggering of episodes may be a productive strategy, informing us not only about postnatal episodes but having implications for the etiology of affective disorders more generally. In addition, our results suggest that the definition of postpartum episode employed is important in studies of the postnatal triggering of depression. Future work should concentrate on episodes with a close temporal relationship to childbirth.

Limitations

The current study must be interpreted in the light of a number of limitations. First, the study group was not systematically ascertained but rather was identified from various sources. It would be very difficult and expensive, however, to systematically recruit a similar number of parous female sibling pairs with recurrent major depression in a community sample.

Second, the study group was limited to those with a positive family history of depression, and it is possible that the results would not generalize to women with major depression unselected for family history. The weight of evidence, however, suggests that it is unlikely that two subtypes of depression exist, one mainly genetic and the other mainly nongenetic

(12,

13), and it is of note that the women were recruited independently of a history of postpartum episodes, which have not been reported to be either more or less common in women with a family history of depression. Further family studies examining postpartum episodes in women unselected for a family history of major depression would be of benefit but would need to be considerably larger than the current study to have reasonable power to replicate the findings reported here.

Third, the assessments of postpartum depression were made retrospectively, in some cases many years after the episode itself. However, childbirth is a memorable event, occurring at most on only a few occasions in a woman’s life. Therefore, it is likely that episodes of major depression occurring in close relationship to childbirth would be well remembered. In addition, we were able to review contemporary case notes of one-third of postpartum episodes and found excellent agreement with the woman’s own account at interview. With regard to onset, for example, in only one case was there no information in the case note record enabling confirmation of the woman’s account of the week of onset following delivery.

Finally, the study does not specify the cause of the apparent familiality, which may be due to either common (shared) environment, genetic factors or—perhaps most likely—a combination of both. The study of Treloar and colleagues

(8) found a moderate heritability for postpartum symptoms of depression, but assessments of postpartum symptoms in this study were not ideal. Further, twin studies employing more robust assessments of narrowly defined postnatal depression would be beneficial. However, given the compelling evidence for the influence of genes in vulnerability to major depression

(12), it is plausible that genetic factors play a role in determining an individual’s susceptibility to depression in the postpartum period. Molecular genetic studies focusing on women who have experienced narrowly defined postpartum depression may therefore prove productive in identifying genetic variants that increase vulnerability to the puerperal triggering of episodes.

Conclusions

Our results suggest that familial factors play a role in determining vulnerability to narrowly defined postpartum depression but have either less or no effect in determining vulnerability to postpartum depressive episodes defined more widely.

If replicated, this narrowly defined subgroup provides a more homogenous group in which to investigate the etiological basis of postpartum depression. A greater understanding of the causes of postpartum depression will facilitate advances in the prevention and treatment of perinatal affective episodes, with obvious benefits to mother and child, and may also provide important clues into the etiology of mood disorders in general.