Research has established a strong relationship between combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and physical health measures

(1 –

16) . This association was observed in veterans from the 1991 Gulf War who experienced increased rates of physical symptoms in all domains in the years after returning from deployment

(1,

4 –

7,

12,

16) . Compared to military personnel who were not stationed in the war zone, 1991 Gulf War veterans showed significantly higher rates of somatic symptoms, more psychological distress, worse general health status, and greater health-related physical and psychosocial functional impairment

(1) . The major limitations of these studies were that they were conducted many years after the veterans returned from combat, were based largely on clinical populations, and did not control for wartime injuries.

Research conducted on veterans from the current war in Iraq has already established the presence of a high prevalence of PTSD (12%–13%) during the first 3–4 months after their return home

(17) . One study conducted among seriously injured hospitalized veterans showed that PTSD was strongly correlated with the level of injury

(18) . However, to date the relationship between PTSD and physical health has not been explored among healthy noninjured veterans. This study evaluated the association of PTSD with physical health measures among Iraq war veterans 1 year after their return from deployment with control for combat injury.

Method

This study was based on self-report survey data obtained from 2,863 soldiers from four Army combat infantry brigades surveyed 1 year after their return from deployment to Iraq. This is part of a larger study looking at the effect of combat on the mental health of soldiers

(17) .

Recruitment and survey collection methods have been described previously

(17) . Briefly, the soldiers were administered the survey at their duty site with written informed consent under a protocol approved by the institutional review board of the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research. All surveys were anonymous. Approximately half of the soldiers from the selected units were available for the survey, with most of those not available because of work or training duties. Over 98% of the available soldiers consented to participate; the rates of missing values for individual items in this study ranged from 2% to 9%; 2% did not complete the PTSD measure.

The study outcomes included past month symptoms of PTSD, depression, alcohol misuse, self-rated health status, sick call visits, missed work days, and somatic symptoms. PTSD was assessed with the well-validated 17-item National Center for PTSD Checklist

(19,

20) . PTSD scoring criteria have been described previously

(17) and required at least one intrusion symptom, three avoidance symptoms, and two hyperarousal symptoms that were at least at the moderate level of severity. In addition, the total score had to be at least 50 on a scale that ranged from 17 to 85. Comorbidity of depression or alcohol misuse with PTSD was measured with the Patient Health Questionnaire Depression Scale—9 and a two-item alcohol screening instrument, respectively, with previously described criteria

(21,

22) .

The soldiers were asked to rate their overall health (excellent, very good, good, fair, or poor), and their responses were dichotomized (“fair” and “poor” were considered worse health). The soldiers were also asked to report the number of sick call (primary care) visits and the number of missed workdays in the past month, both dichotomized at two or more.

Somatic symptoms were measured with the 15-item Patient Health Questionnaire—15

(23) . The symptoms were scored, per established criteria

(23), as 0 (not bothered at all), 1 (bothered a little), or 2 (bothered a lot), except for sleep disturbance and fatigue, which were scored as 0 (not at all), 1 (few or several days), or 2 (more than half the days or nearly every day). A total sum of ≥15 indicated high somatic symptom severity based on data from primary care settings

(23) .

SPSS version 12.0 software for Windows (SPSS, Chicago) was used to conduct the Pearson’s correlation analyses, analyses of variance, and chi-square tests. Because physical symptoms and PTSD can both be related to injuries sustained during deployment

(18,

24), we asked the participants if they had been wounded or injured during their most recent deployment and controlled for this potential confounder with stratified analyses.

Results

The demographic characteristics of the 2,863 soldiers surveyed were similar to those of the general active duty infantry army population

(17) . The participants were predominantly young (80.5% were less than 30 years old), nearly all male (97.2%), and largely junior enlisted (55.9% ranked E-1 to E-4). The percentage of participants who reported being wounded or injured was 17.1% (471 of 2,758).

The prevalence of PTSD was 16.6% (468 of 2,815), compared with a predeployment prevalence of 5% for a comparable group

(17) . Injury was associated with a higher rate of PTSD. Of those wounded or injured at least once, 31.8% (150 of 471) met PTSD criteria, compared to only 13.6% (311 of 2,287) of those never injured (χ

2 =93.43, df=1, p<0.0001; odds ratio=2.97, 95% confidence interval [CI]=2.36–3.73).

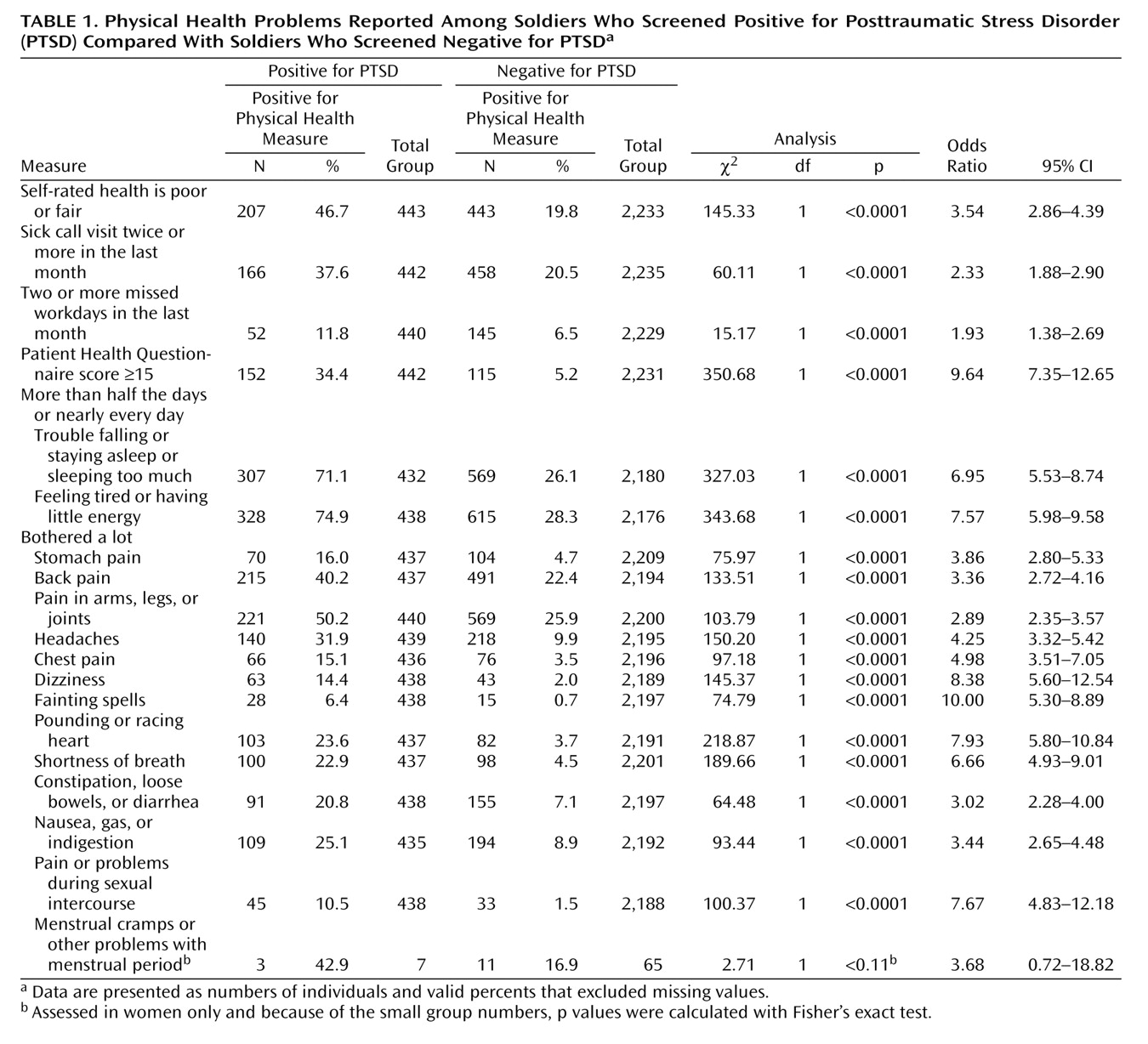

There were strong associations between PTSD and physical health measures (

Table 1 ). Poor self-rated health, two or more sick call visits, two or more missed workdays, and somatic symptoms were endorsed significantly more often by those who screened positive for PTSD than those who did not (

Table 1 ). The association of PTSD with poor self-rated health, sick call visits, and missed workdays remained significant after control was added for injury sustained during combat by use of stratified analysis (data not shown).

Of the PTSD symptom clusters, all were significantly correlated with higher Patient Health Questionnaire—15 scores, with symptoms of increased arousal having the highest correlation (reexperiencing: r=0.454, p<0.01; avoidance: r=0.498, p<0.01; increased arousal: r=0.525, p<0.01). Psychiatric comorbidity strengthened the association of PTSD with physical health measures. The mean Patient Health Questionnaire—15 score for those without PTSD was 6.0 (SD=4.8), whereas it was 10.2 (SD=5.3) for those with PTSD only, 11.2 (SD=6.1) for those with PTSD and alcohol misuse, 14.8 (SD=5.4) for those with PTSD and depression, and 16.6 (SD=5.3) for those with all three conditions.

Discussion

We examined the prevalence of PTSD and its association with self-rated health, sick call visits, missed workdays, and physical symptoms among largely uninjured Iraq war veterans 1 year after their return from combat. Although it is not known what the optimal time point is to measure these associations, 1 year is still proximal to the deployment compared with previous studies

(1,

4 –

7,

12,

16) but also should be a sufficient time period to resolve or stabilize most immediate postdeployment medical issues. We found that all health measures were strongly associated with PTSD at this time point, even after we controlled for injury sustained in combat. Approximately one-third of the soldiers who screened positive for PTSD had high somatic symptom severity. PTSD has been shown to predict poor health not only in veterans of the 1991 Gulf War

(1,

4 –

7,

12) but also in veterans of World War II and the Korean War

(3) . Our study extends these findings in a group of active duty soldiers returning from recent combat deployment to Iraq, confirming the strong association between PTSD and the indicators of physical health independent of physical injury.

The correlation of increased arousal with higher Patient Health Questionnaire—15 scores and the finding that psychiatric comorbidity strengthens the associations of PTSD with poor health supports other studies that have examined the mechanisms underlying these relationships. The strong association of health measures with PTSD may be mediated by biological (e.g., autonomic hyperarousal, disturbed sleep physiology, and altered hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis activity), psychological (e.g., hostility, poor coping, hopelessness), attentional (e.g., heightened symptom perception and somatization), and behavioral (e.g., high-risk behaviors, such as smoking and drinking) processes

(15,

25) .

There are several limitations of the study that should be considered. The cross-sectional self-report design limits our ability to make causal inferences. We cannot estimate the extent to which the reduced quality of health is an accurate reflection of soldiers’ current medical status or is due to changes in the perception of health among those with PTSD. Self-report surveys are not equal to clinician interview-based measures. However, the strength and consistency of the observed associations with well-validated clinical scales and the biological and epidemiological plausibility of the findings

(1 –

16) support the value of this approach. The study findings, based only on soldiers from combat infantry units, are not generalizable to the army population at large or to the population of all soldiers who have deployed but are representative of the soldiers at highest risk of exposure to combat

(17) . A related limitation is that the study group was not randomly selected. Although availability was largely determined by the work schedule, the soldiers who deployed with these units but had separated from them because of medical problems or soldiers who were attending medical appointments on the days that the surveys were collected were not included in the study. Thus, the study results reflect data from the healthiest segment of the working infantry population. Because this would exclude the more severely wounded or medically ill soldiers on the days of the surveys, the prevalence rates may be conservative.

Recent publications have shown that PTSD is highly prevalent among soldiers returning from combat duty in Iraq and that the severity of wartime injuries is correlated with PTSD among seriously injured hospitalized veterans

(17,

18) . This study indicates that the medical burden of PTSD encompasses a variety of physical health problems among healthy soldiers evaluated in their units 1 year after return from deployment. The study findings have broad implications for health professionals in the military, the Veterans Administration, and civilian primary care and specialty medical practice settings who treat veterans. The study indicates that veterans who have served in combat and are seen with significant physical symptoms should be evaluated for PTSD and vice versa. Early detection and treatment strategies in primary care settings may help to reduce stigma and barriers to care. Further research is needed to determine the optimal service delivery strategies.