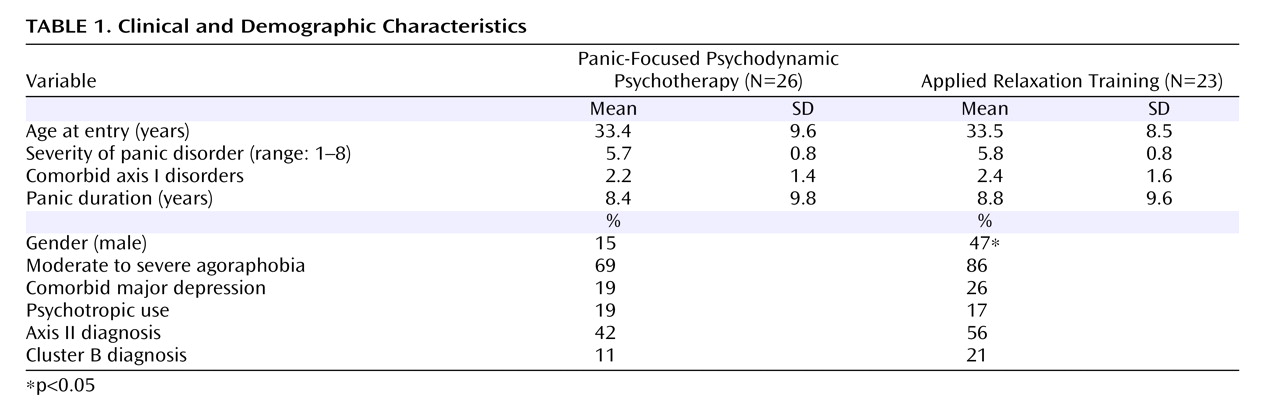

This was a randomized controlled clinical trial of panic-focused psychodynamic psychotherapy and applied relaxation training for subjects with primary DSM-IV panic disorder with and without agoraphobia. Subjects were randomly assigned using a computer generated treatment assignment list that was stratified by presence or absence of 1) comorbid current DSM-IV major depression and 2) stable doses of antipanic medication. The trial was conducted between July 2000 and Jan. 2004 and approved by the Weill Medical College Institutional Review Board.

Subjects

To meet entrance criteria, subjects required diagnosis with primary DSM-IV panic disorder, with or without agoraphobia, and a minimum severity score of 5 on the 0- to 8-point Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM-IV, Lifetime Version

(18), whether or not they were taking antipanic medication. Patients had a minimum of one weekly panic attack.

All subjects signed informed consent. Subjects meeting study entrance criteria while taking stable doses of medication agreed to keep medication type and dose constant throughout the study (total patients: N=9; applied relaxation training patients: N=4; panic-focused psychodynamic psychotherapy patients: N=5). Study psychiatrists prescribed such medication when present to ensure stability; all were on standard antipanic doses of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). Patients discontinued ongoing psychotherapy to gain study entrance. Patients with comorbid major depression, personality disorders, and severe agoraphobia were included, making this cohort more symptomatic than in many prior panic disorder studies

(9 –

11), yet more representative of panic disorder as described in the clinical epidemiological literature

(6 –

9) . Psychosis, bipolar disorder, and active substance abuse (6 months remission necessary) were exclusions.

Assessments

Independent evaluators, blinded to subject condition and therapist orientation, assessed subjects at baseline, treatment termination, and at 2, 4, 6, and 12 months posttreatment termination (

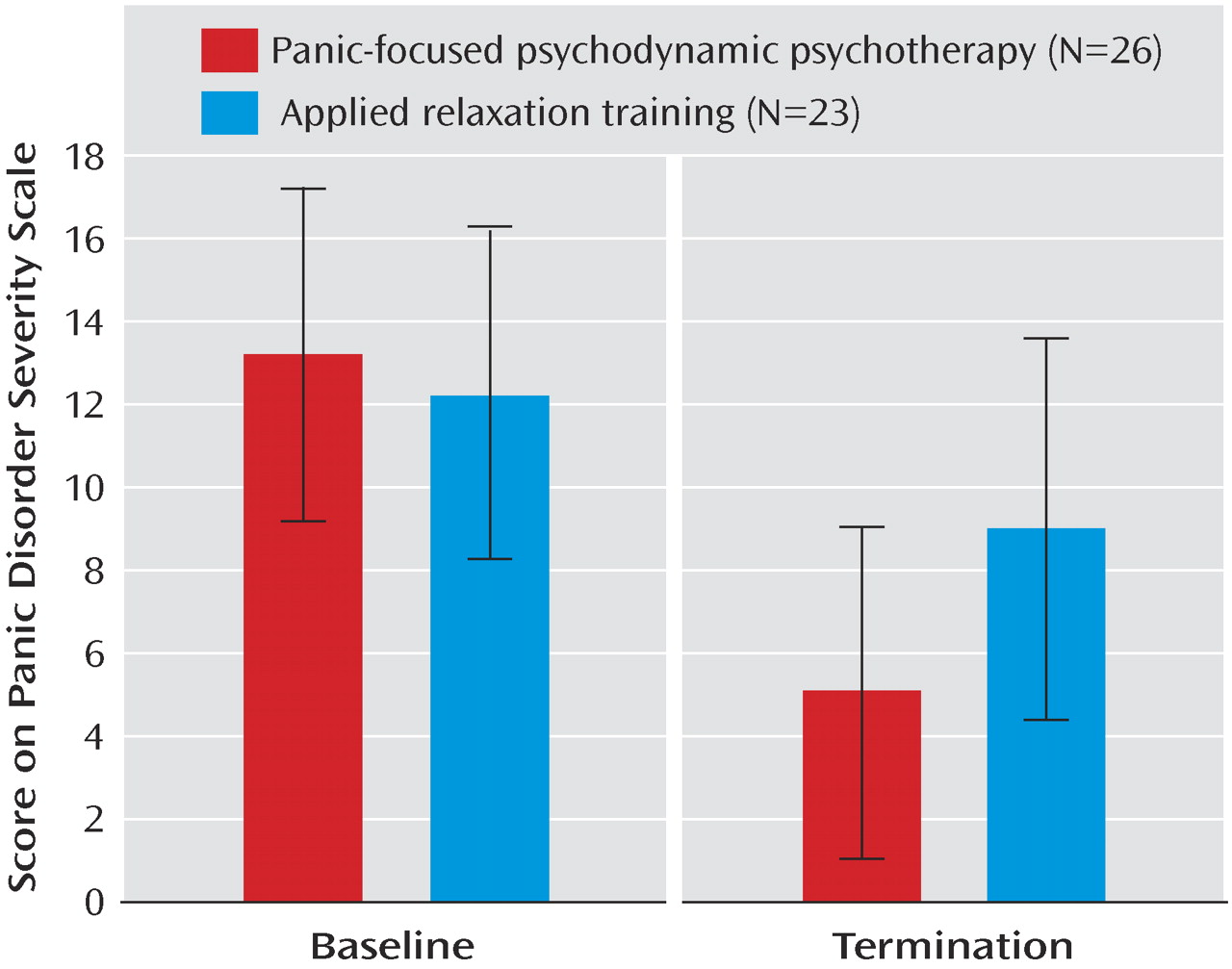

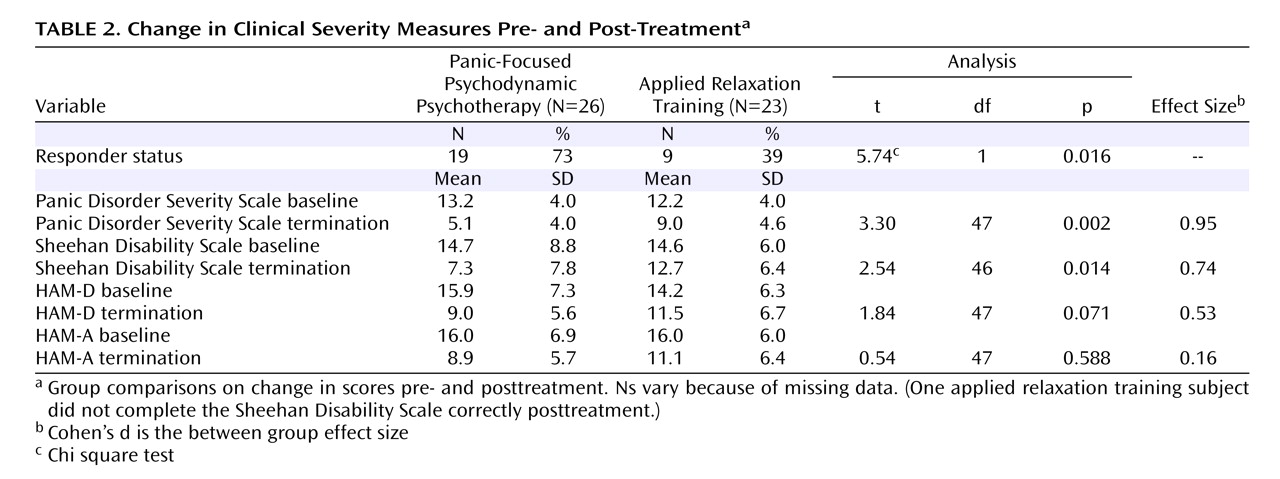

Figure 1 ). The primary outcome measure was the Panic Disorder Severity Scale

(19) (

Figure 2 ), a clinician-administered instrument monitoring the number of panic attacks, limited symptom attacks, agoraphobic avoidance, and somatic sensitivity. The Panic Disorder Severity Scale was analyzed as a continuous measure, although the criterion for “response” that has become standard

(9) —a 40% reduction from the baseline Panic Disorder Severity Scale score–is determined categorically. Other measures included the Sheehan Disability Scale

(20), a measure of psychosocial impairment; the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D); and the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HAM-A), a measure of nonpanic anxiety.

Training of Independent evaluators

Independent evaluators were trained for criterion on the Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM-IV, Lifetime Version. All evaluators were master’s level diagnosticians with >35 hours training on the Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM-IV, Lifetime Version and >12 hours of training on symptom scales. To evaluate rater drift and monitor interrater reliability, the Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM-IV, Lifetime Version raters co-rated two subjects every 9 months. Interrater reliability of each assessment measure was examined using two independent raters (one of whom conducted the interview) for each of five subjects (Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM-IV, Lifetime Version, kappa=0.91; Panic Disorder Severity Scale, kappa=0.89).

Interventions

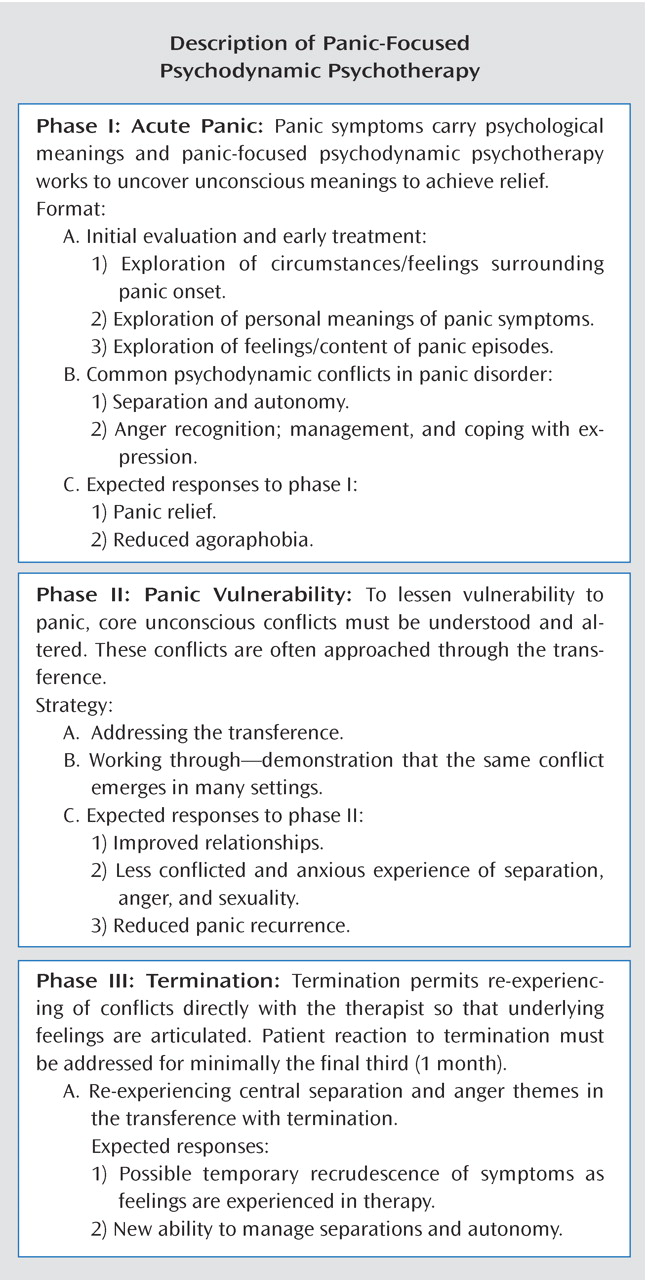

Panic-focused psychodynamic psychotherapy is a 24-session, twice-weekly (12 week), manualized psychoanalytic psychotherapy

(1) . It showed promising preliminary outcome results in an open trial

(23,

24) . This therapy uses substantially different techniques than CBT (see

Figure 1 for panic-focused psychodynamic psychotherapy description). There is no homework or exposure protocol in panic-focused psychodynamic psychotherapy.

Applied relaxation training in this study is a 24-session, twice-weekly, manualized psychotherapy. Treatment starts with a three-session rationale and explanation about panic disorder. Applied relaxation training utilizes progressive muscle relaxation techniques and exposure. Progressive muscle relation training involves focusing attention on particular muscle groups, tensing the muscle group for 5–10 seconds, attending to sensations of tension, and relaxing the muscles. The training also involves therapist suggestions of deepening relaxation, attending to differences between sensations of tension and relaxation, and suggestions of deepening relaxation. The number of muscle groups is gradually reduced from 16 to eight to four. Discrimination training, generalization, relaxation by recall, and cue-controlled relaxation (pairing the relaxed state to the word “relax”) follow. One section addresses relaxation-induced panic.

Home practice is required twice daily. By week 6, subjects apply relaxation skills to anxiety situations in a graduated manner. Subjects learn to identify early stages of anxiety, to use relaxation as an active coping strategy whenever they become aware of tension, and to practice relaxation regularly throughout the day in various situations to maximize generalization. Applied relaxation training involves daily assigned homework and an exposure protocol.

Applied relaxation training has been used in five controlled trials

(12) and demonstrated efficacy for panic disorder in one

(16) . It has been found less efficacious than CBT in other studies

(8,

10,

25) . Applied relaxation training is an active comparison treatment, controlling for therapist contact, expertise, and expectancy of improvement, potentially important threats to internal validity. Despite its being somewhat less potent than CBT, panic disorder patients find applied relaxation training credible and attractive. To our knowledge, no studies have found applied relaxation training less credible for panic disorder than alternatives such as CBT. In a study comparing CBT to applied relaxation training

(16), panic disorder patients rated applied relaxation training and CBT equally high on credibility and expectancy for improvement.

We chose to test panic-focused psychodynamic psychotherapy against a less active control psychotherapy in this first efficacy test rather than against the better established CBT for several reasons. In the first tests of new treatments, comparison treatments are preferable to empirically validated reference treatments

(26,

27) .

1) There are no well-established margins for testing equivalence in panic disorder, a

sine qua non for equivalence studies

(28) . The Food and Drug Administration’s Guidance Document

(28,

29) states: “In order to implement an equivalence or noninferiority trial, the magnitude [of medication] effect must be stable and well-established in the literature, with consistent results seen from one trial to the next” (

28, p.32). We have not yet reached this juncture in panic disorder studies. All researchers would agree that a 1-point Panic Disorder Severity Scale score difference is not clinically significant, but it is unclear whether panic researchers would agree on the significance of a 2- or 3-point difference in the Panic Disorder Severity Scale outcome. (As a frame of reference, the standard deviation at the end of the multicenter randomized controlled clinical trial study was 4.55.) Furthermore, the margin of equivalence must be substantially smaller than the hypothesized treatment effect that is used to determine cohort size in a superiority trial.

2) Even if the field had agreed on a margin of equivalence, the cohort size needed for an equivalence study would have exceeded that required by our study design.

Therapists

Panic-focused psychodynamic psychotherapy therapists (N=8)

Panic-focused psychodynamic psychotherapy therapist training comprised a 12-hour course. All panic-focused psychodynamic psychotherapy therapists were M.D. physicians who had completed psychiatric residency or Ph.D. psychologists, with specific training in panic-focused psychodynamic psychotherapy entailing a 12-hour course and a pilot supervised videotaped case as well as a minimum of 2 years of clinical experience treating panic disorder using psychodynamic psychotherapy. All had completed at least 3 years of psychoanalytic training at an institute. For panic-focused psychodynamic psychotherapy therapists, the mean amount of experience was 21 years (range: 2–40 [SD=8.6] years).

Applied relaxation training therapists (N=6)

Applied relaxation training therapists were M.D. physicians who had completed psychiatric residency or Ph.D. psychologists, with specific training in applied relaxation entailing a 6-hour course, a pilot supervised videotaped case, and a minimum of 2 years of clinical experience treating panic disorder patients with applied relaxation training and CBT. All applied relaxation training therapists had extensive CBT experience for panic disorder and used some form of relaxation training in their routine practice; two therapists used applied relaxation training routinely in practice. For applied relaxation training therapists, the mean experience was 16 years (range: 5–35 [SD=11.3] years) (Mann-Whitney: p=0.66 between therapist groups).

Ongoing Supervision

Therapists in both modalities met monthly for group supervision and received individual supervision as needed. Therapists in both modalities were monitored for adherence to treatment protocol by adherence raters in each modality with equal frequency. Three videotapes were rated for adherence per individual treatment. All therapists met predetermined adherence standards. For panic-focused psychodynamic psychotherapy therapists, the cutoff for acceptable adherence was a score of 4 out of 6 on at least five of seven items on the Panic-Focused Psychodynamic Psychotherapy Adherence Rating Scale (available from the authors). Four raters determined reliability by applying the Panic-Focused Psychodynamic Psychotherapy Adherence Scale to videotapes of panic-focused psychodynamic psychotherapy sessions. The mean interrater intraclass correlation was 0.92 (N=50). The average panic-focused psychodynamic psychotherapy therapist adherence was 5.5.

For applied relaxation training therapists, required scores were 5 out of 7 on all three items scored for the rated session on the Applied Relaxation Training Adherence Scale (unpublished instrument of MW Otto and MH Pollack available from Dr. Milrod upon request). All psychotherapy sessions were videotaped for adherence monitoring. Applied relaxation training adherence raters from Boston University assisted us with applied relaxation training adherence monitoring. Applied relaxation training therapists achieved an average adherence rating of 6.2 out of 7 points (tapes for each therapist, N=12).

Data Analytic Procedures

The analyses were conducted in accordance with the plans specified in the protocol. The demographic and clinical characteristics of the randomly assigned groups were compared using t tests for continuous variables and chi square or Fisher’s exact tests for categorical variables. Efficacy was evaluated with t tests comparing groups on change from baseline for each primary and secondary efficacy measure. Response rates were compared using chi square tests. Secondary analyses involved a multiple linear regression analysis approach to analysis of covariance. Covariates included gender, baseline of the Panic Disorder Severity Scale, baseline of the Sheehan Disability Scale, depression, and dropout status. The assumption of no covariate by treatment interaction was evaluated for each covariate

(30) . A two-tailed alpha level was used for each statistical test. Alpha was not adjusted for tests of efficacy because one primary dependent variable (Panic Disorder Severity Scale) was specified

a priori . The intention-to-treat principle was employed by carrying the last observation forward, which by design was the baseline assessment for subjects who did not complete the study if they refused assessment at the time of dropout.