Nonsuicidal self-injury, which refers to the direct, deliberate destruction of one’s own body tissue without suicidal intent, is a pervasive problem

(1) . A long-standing limitation in the assessment of self-injurious thoughts is the reliance on an individual’s self-report of such thoughts, as such measures can introduce problems in risk assessment and clinical decision making because they are prone to concealment in order to avoid unwanted treatment, such as involuntary hospitalization. Moreover, research suggests that self-report measures are insensitive to implicit thoughts, or those occurring outside of conscious awareness

(2) .

To address these problems with self-reports, researchers have developed performance-based methods for assessing sensitive and stigmatized behaviors. One such method is the Implicit Association Test

(3,

4), a reaction-time test that measures individuals’ less controllable, automatic associations with a concept of interest

(5) . Briefly, the Implicit Association Test uses the fact that people classify related concepts (e.g., “flowers” and “pleasant”) together more quickly than less related concepts (e.g., “insects” and “pleasant”) to measure the mental associations they hold about different constructs of interest (for demonstration tests, see https://implicit.harvard.edu/implicit/). The Implicit Association Test may be a useful clinical tool, as it is predictive of future behavior

(6), sensitive to clinical change

(7), and resistant to attempts to feign desirable qualities

(8) . This final feature makes the test especially valuable for the assessment of behaviors for which there is motivation to conceal one’s true thoughts or intentions, such as self-injury.

The current research was aimed at developing and examining a performance-based measure of the associations individuals hold about self-injurious thoughts, the Self-Injury Implicit Association Test. We examined whether people with a recent history of nonsuicidal self-injury perform differently from noninjurious people on this test. If so, this would be, to our knowledge, the first evidence of a behavioral test that can distinguish between self-injurers and noninjurers. Next, as a test of the potential clinical utility of the instrument, we examined whether it improves the prediction of nonsuicidal self-injury beyond that achieved with known demographic and psychiatric risk factors.

Method

The participants were 89 (68 female) adolescents with a mean age of 17.10 years (SD=1.92, range=12–19) who identified themselves as European American (73.0%), African American (3.4%), Hispanic (6.7%), Asian American (11.2%), or having mixed or other ethnicity (5.6%). The participants included those with a recent (past year) history of nonsuicidal self-injury (N=53) and a noninjurious comparison group (N=36). This group size provided strong statistical power (0.96) to detect the large between-group differences (d=0.80, alpha=0.05, two-tailed) required for the Self-Injury Implicit Association Test to be a useful clinical tool. Participants were recruited through announcements posted in psychiatric clinics, newspapers, community bulletin boards, and the Internet. All procedures were approved by Harvard University’s institutional review board. Written informed consent was obtained for all participants, with parental consent for those less than 18 years old.

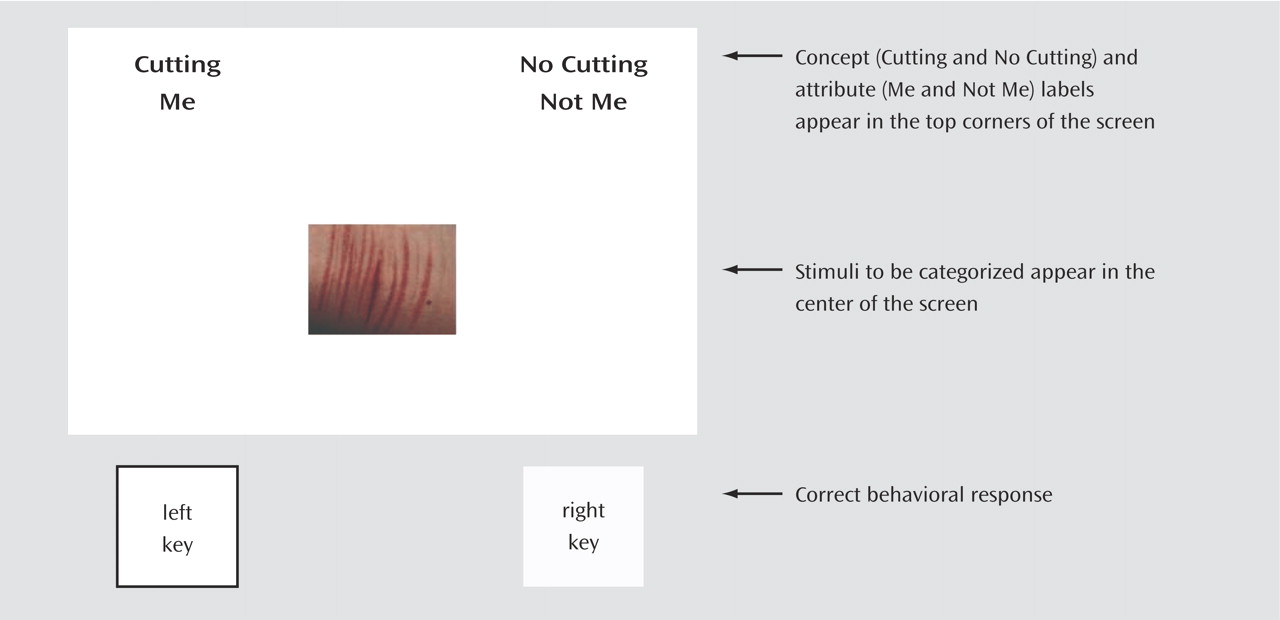

All of the assessments were completed during one session in a behavioral research laboratory. We examined two versions of the Self-Injury Implicit Association Test: one that measures how strongly individuals associate self-injury with themselves (the identity version) and one that measures the automatic association of self-injury with evaluative positivity (the attitude version). The two versions were developed, administered, and scored according to standard procedures for the Implicit Association Test

(3) . Briefly, each participant was seated alone at a desktop computer and instructed to classify stimuli that appeared in the center of the computer screen as quickly as possible by pressing two keys: “e” for stimuli to be classified on the left of the screen and “i” for stimuli classified on the right.

The identity version of the Self-Injury Implicit Association Test tested the strength of the association an individual holds between self-injury and him- or herself. The participants were presented with a series of images that were either related to self-injury (i.e., pictures of skin that had been cut) or neutral (i.e., pictures of noninjured skin) and were asked to classify these as quickly as possible as representing the concept “Cutting” or “No Cutting.” We intentionally focused only on cutting to limit variability in the experimental procedures and because prior work indicates that cutting is the primary method of nonsuicidal self-injury

(9) . Of the current 53 self-injurers, 51 (96.2%) reported using cutting, among other methods, for self-injury. In the identity version of the test, participants also were presented with words that were either self-relevant (e.g., “I,” “Mine”) or other-relevant (e.g., “They,” “Them”) and were asked to classify these as quickly as possible as representing the attributes “Me” or “Not Me.” Correct classifications were followed by presentation of the next stimulus, and incorrect classifications were followed by presentation of a red “X,” which remained until the correct key press was made.

For the first critical test block (presented in random order) the participants were instructed to press the same computer key in response to both “Cutting” and “Me” stimuli (thus pairing stimuli related to self-injury and oneself) and the other computer key for “No Cutting” and “Not Me” stimuli (

Figure 1 ). For the second critical test block, the opposite sorting was performed (i.e., pairing stimuli related to noninjuring and oneself). Response latencies in these two blocks were recorded and analyzed by using a standard Implicit Association Test scoring algorithm

(3) . The relative strength of the association between self-injury and oneself was indexed by calculating a standardized D score for each participant by subtracting the mean response latency for the Cutting/Me test block from the mean response latency of the Cutting/Not Me test block and dividing by the standard deviation of the response latency for all trials. Thus, positive D scores reflect faster responding (i.e., stronger associations) when self-injury and oneself are paired, whereas negative D scores reflect slower responding (i.e., weaker associations) when self-injury and oneself are paired.

Our second form of the test, the attitude version, followed the same procedures but used the categories of “Good” (e.g., “Pleasure,” “Relief”) and “Bad” (e.g., “Painful,” “Ineffective”) instead of the categories of “Me” and “Not Me.”

Demographic factors including age, sex, and race/ethnicity were assessed in face-to-face interviews. To ensure that between-group differences on the Self-Injury Implicit Association Test were not due to differences in IQ, all participants also were assessed with the Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence

(10) . Psychiatric disorders are associated with nonsuicidal self-injury

(11,

12), and therefore they were assessed by using the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children—Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS-PL)

(13) . Given their associations with self-injury, we focused specifically on disorders of mood (major depression, bipolar disorder), anxiety (panic, separation anxiety, phobias, generalized anxiety, and obsessive-compulsive disorder), impulse control (oppositional defiant, conduct, and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder), eating (bulimia nervosa, anorexia nervosa), and substance use (alcohol, drugs). Level of clinical severity was measured by using the Children’s Global Assessment Scale

(14) . The presence of nonsuicidal self-injury in the past year was assessed by using the Self-Injurious Thoughts and Behaviors Interview, a structured interview with strong interrater reliability, test-retest reliability, and construct validity (Nock et al., unpublished manuscript, 2006).

Performance results on the two versions of the Self-Injury Implicit Association Test (i.e., D scores) for the two groups were compared by using t tests. The ability of the instruments to add incrementally to the prediction of nonsuicidal self-injury was tested by using two separate hierarchical logistic regression analyses (one for each test version) in which demographic factors (age, gender, race/ethnicity) were entered in the first step, psychiatric factors (full-scale IQ, presence of each class of disorder, total number of disorders, and score on the Children’s Global Assessment Scale) were entered in the second step, and D scores were entered in the third step.

Results

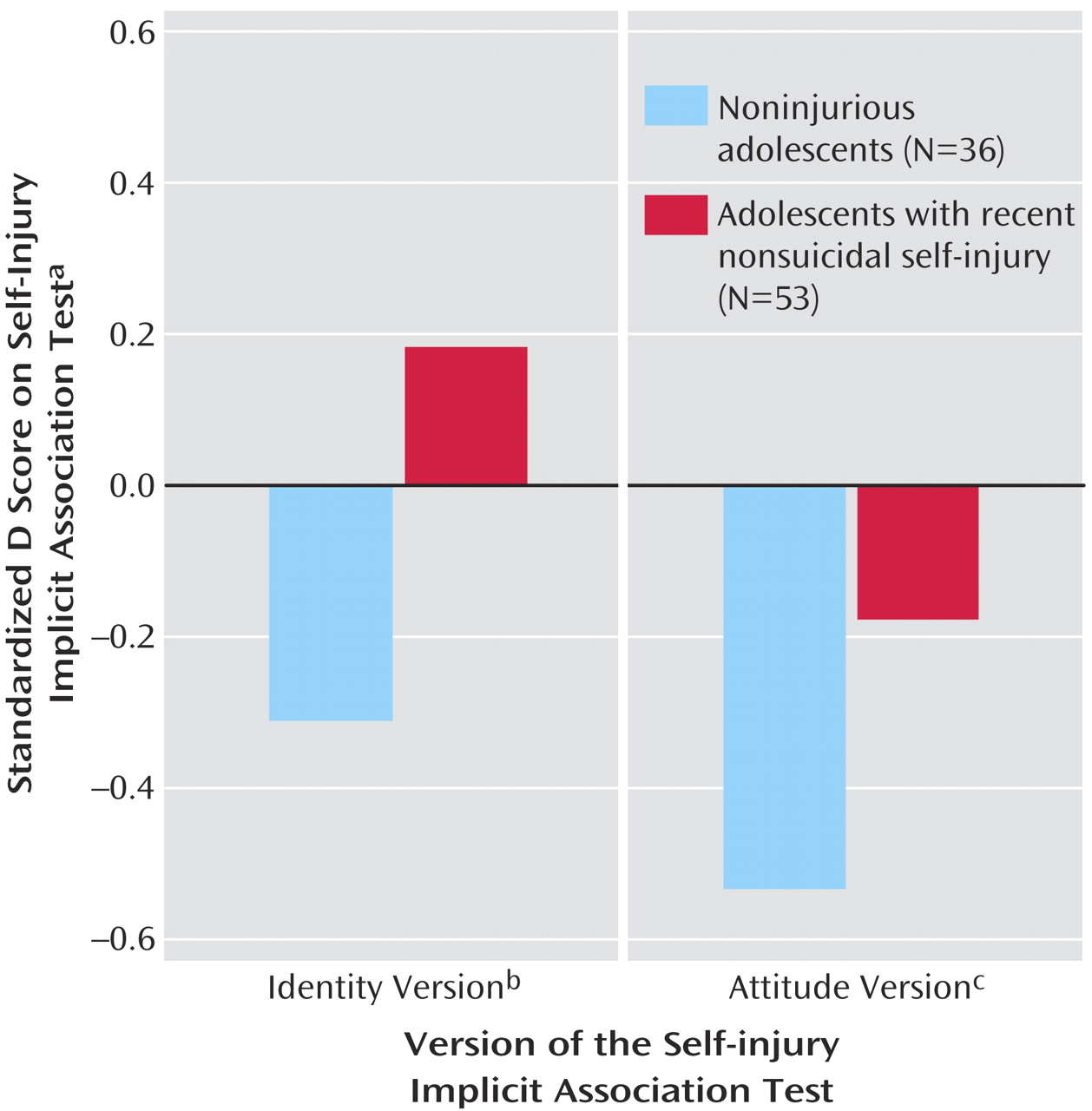

Analyses revealed large and statistically significant differences between the self-injurers and noninjurers on the identity version of the Self-Injury Implicit Association Test (

Figure 2 ). As presented on the left side of the figure, those engaging in nonsuicidal self-injury showed a positive association (D score) between “Cutting” and “Me” (mean=0.18, SD=0.45), while the noninjurers showed a negative association (mean=–0.31, SD=0.34). Analyses also revealed a large and statistically significant difference on the attitude version of the test. As presented on the right side of

Figure 2, both groups showed a positive association between “Cutting” and “Bad,” but the association was significantly stronger for the noninjurers (mean=–0.53, SD=0.29) than for those engaging in self-injury (mean=–0.16, SD=0.41).

In terms of incremental predictive validity, after accounting for the variance explained by the demographic (χ 2 =6.00, df=3, R 2 =0.09, p=0.12) and psychiatric (χ 2 =38.66, df=8, ΔR 2 =0.44, p<0.001) factors, we found that performance on both the identity version (χ 2 =10.38, df=1, ΔR 2 =0.18, p=0.001) and attitude version (χ 2 =4.74, df=1, ΔR 2 =0.14, p=0.03) of the Self-Injury Implicit Association Test independently and significantly improved the statistical prediction of nonsuicidal self-injury. Notably, scores on the two versions were correlated (r=0.50, N=89, p<0.001), and when entered simultaneously in the third step of the regression equation, the identity version continued to significantly predict self-injury (odds ratio=11.32, p=0.02), whereas the attitude form of the test did not (odds ratio=2.87, p=0.31).