Brain tumors are a well-known cause of frontal lobe dysfunction. One type is the rare dysembryoplastic neuroepithelial tumor, a benign supratentorial neoplasm seen primarily in children and young adults

(5,

6) . Approximately one-third of dysembryoplastic neuroepithelial tumors occur in the frontal lobes, and some become large enough to compress regions of the cortex and white matter to the point of disrupting behavior

(7 –

9) . In addition to mass effects, dysembryoplastic neuroepithelial tumors are a source of epileptogenic activity, which may lead to neuropsychiatric sequelae when there is frontal lobe involvement

(10,

11) . Surgical resection, which characteristically yields an excellent prognosis, is the recommended treatment for these tumors

(12,

13) . Even with partial tumor removal, there is little evidence of recurrence, and most patients make a complete but slow neuropsychiatric recovery. This case study is one of a few to report the virtually instantaneous neurosurgical cure of a psychiatric illness in a patient with a frontal lobe dysembryoplastic neuroepithelial tumor. We also provide a summary and review of the literature on psychiatric disturbances associated with various frontal lobe lesions.

Discussion

Many studies of humans and nonhuman primates have established that lesioning the frontal lobes can result in abnormal behaviors

(14,

15) . Depending on the affected hemisphere and the location within the hemisphere, human frontal lobe lesions can result in alterations in attention, insight, mood, planning, and interpersonal communication—changes that are often permanent

(15) .

In each hemisphere, the bulk of the nonmotor frontal lobe is subdivided into the prefrontal anterior cingulate and the dorsolateral, orbitofrontal, and ventromedial cortices. The dorsolateral cortex receives the majority of its distant afferent inputs by means of the superior longitudinal and uncinate fasciculi, and short-range association fibers (U-fibers) mediate local prefrontal connections. Medially, the orbitofrontal cortex connects to limbic structures by means of the uncinate fasciculus and to the ventromedial cortex through U-fibers. The orbitofrontal and ventromedial cortices are reciprocally interconnected, and it is likely that both are connected with the anterior cingulate by means of fibers of the rostral cingulum. Communication between the prefrontal cortices of the cerebral hemispheres is mediated by reciprocal callosal projections, but these are generally much sparser than ipsilateral corticocortical connections and are usually limited to homotopic areas

(16 –

18) . In addition to corticocortical connections, all prefrontal areas receive robust input from the limbic channel of the basal ganglia.

The dorsolateral prefrontal cortex plays an essential role in weighting and integrating impulses from various sensory and limbic channels for the purpose of generating goal-directed behaviors

(19) . This brain region is also active in working memory tasks

(20 –

22) . Thus, major features of dorsolateral lesions regularly include labile affect, depression, and decreased executive function

(19,

23 –

25) . Functional imaging studies have linked the negative symptoms of schizophrenic patients to perturbations of dorsolateral cortical metabolism

(26,

27) .

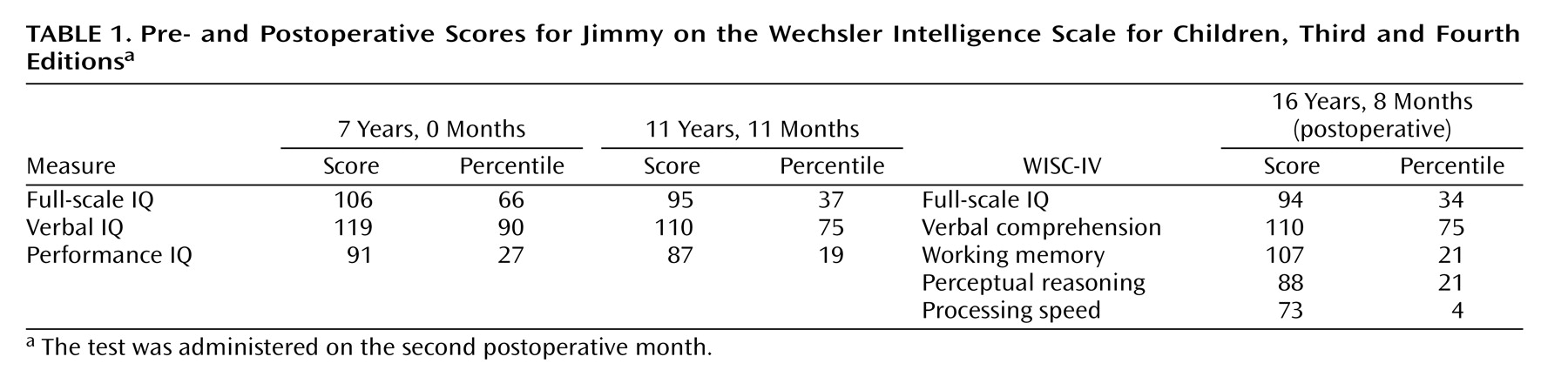

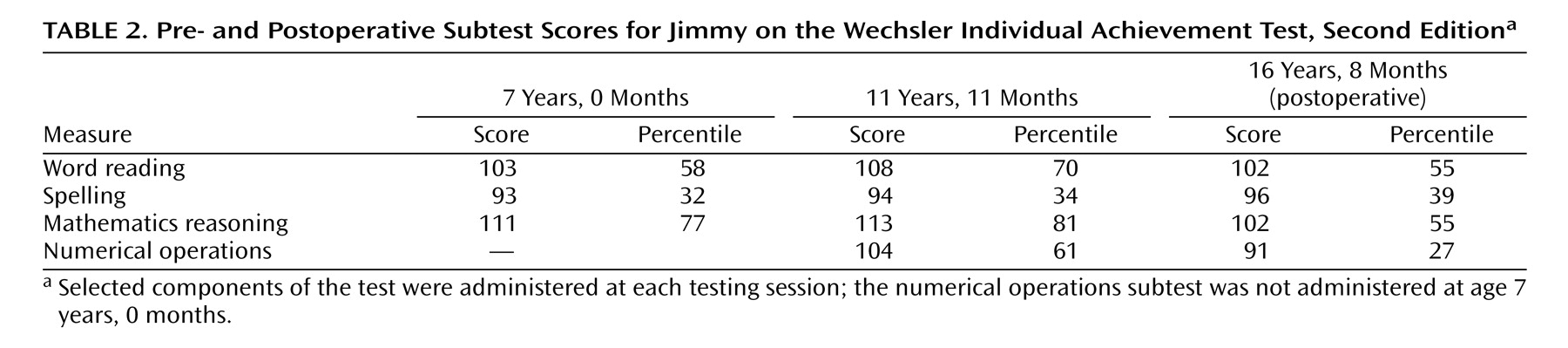

Although our patient’s decreased academic performance might suggest a lesion of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and/or the underlying white matter, other functions subserved by the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, such as decision making, working memory, and capacity to plan

(1,

2,

20 –

22 ), were largely spared. Thus, we surmise that our patient’s dorsolateral cortex remained intact, a conclusion most strongly supported by serial imaging studies that showed that the dysembryoplastic neuroepithelial tumor was many centimeters away from the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. We believe our patient’s decreased school performance was more directly related to the tumor’s effects on other prefrontal areas and to the side effects of the polypharmacy intended to treat his psychiatric symptoms.

Intact orbitofrontal cortices are required for normal judgment and socialization. Patients with orbitofrontal lesions tend to be disinhibited

(24,

28) . Unlike dorsolateral lesions, orbitofrontal lesions generally spare cognitive abilities and volition, but they can significantly contribute to the genesis of antisocial behaviors, prompting some authors to rename the orbitofrontal syndrome acquired “pseudopsychopathy”

(28,

29) . Indeed, the outbursts, mood fluctuations, self-mutilation, and splitting behaviors seen in borderline personalities may be related to a hypofunctioning orbitofrontal cortex

(30,

31) . Neuroanatomically, the explosive antisocial traits associated with orbitofrontal lesions have been postulated to result from a loss of inhibitory control over the amygdala

(28,

32,

33) .

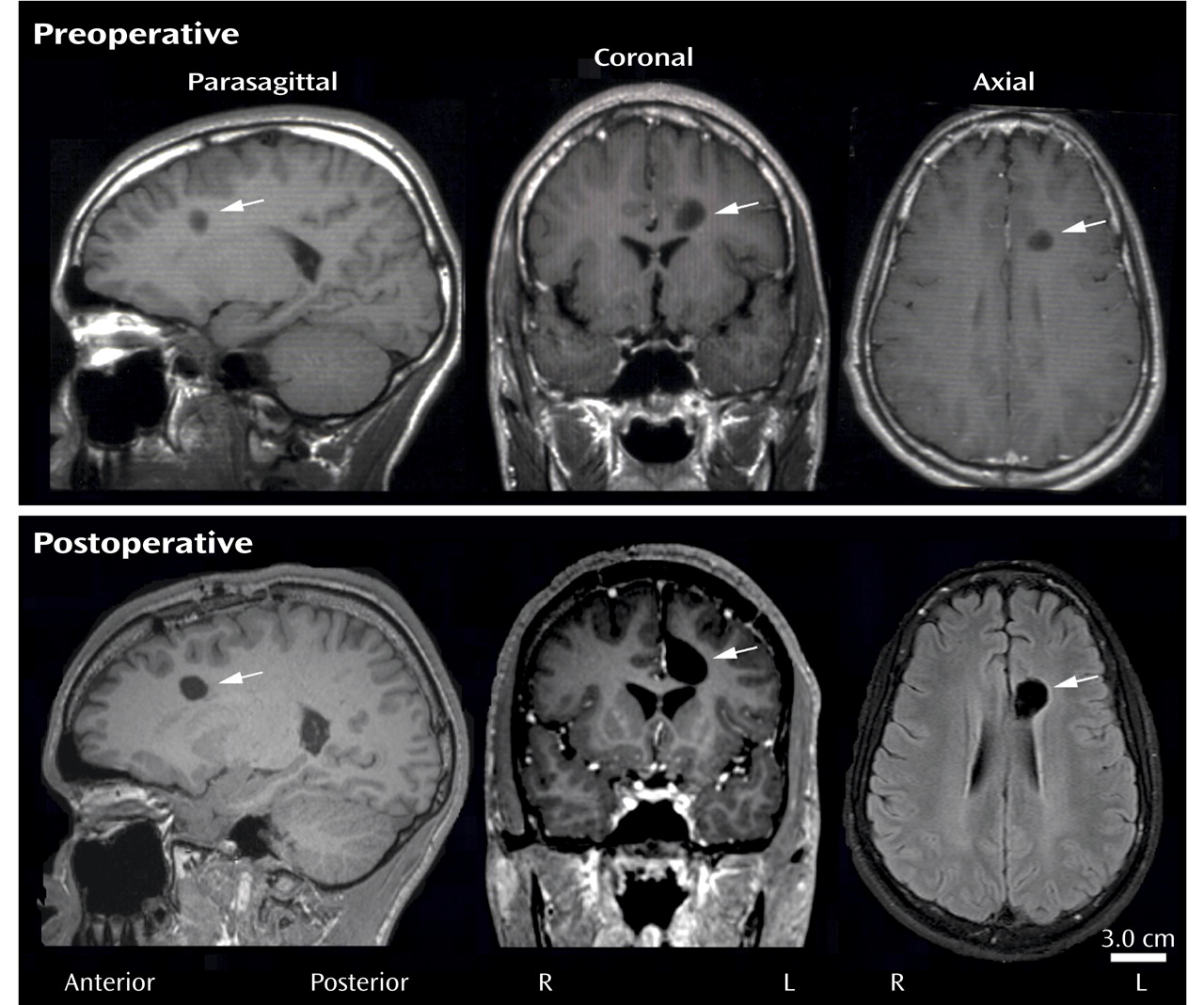

Although our patient exhibited many antisocial behaviors strongly associated with an orbitofrontal lesion, his tumor was not located within the orbitofrontal cortex. This incongruency might be explained by the fact that his tumor was strategically situated in the white matter just superior to the anterior horn of the left lateral ventricle. Tumors in this location can compress corticofugal orbitofrontal axons as they join the uncinate fasciculus. Thus, in our patient, corticofugal orbitofrontal fibers may have been compromised enough to partially denervate the amygdala and uncover behaviors that are normally suppressed.

The ventromedial prefrontal cortex is believed to regulate empathy, foresight, and reversal learning

(14,

34) . In reversal learning tasks mediated by the ventromedial cortex, subjects are trained to respond differentially to two stimuli under reward and punishment conditions, and later they are trained to reverse the reward values

(35) . Reversal learning deficits cause patients to persist in simple tasks or deleterious high-risk behaviors that in the past paid dividends, as, for example, in pathological gambling, where high-risk behaviors persist despite reduced payoffs

(36,

37) .

Our patient exhibited significant signs of reversal learning impairment as evidenced by his repeatedly engaging in high-stakes behaviors that had been rewarded on the streets but resulted in harsh punishment in the residential treatment facility. These negative behaviors are consistent with dysfunction of the ventromedial cortex, an interpretation further supported by MRI studies showing that the dysembryoplastic neuroepithelial tumor encroached on the caudal boundary of the ventromedial cortex. Based on this proximity, it is very likely that the dysembryoplastic neuroepithelial tumor, by either compression or ephaptic activation of corticofugal axons, perturbed ventromedial efferent impulses and mimicked features of a ventromedial cortical lesion.

The anterior cingulate cortex borders the genu of the corpus callosum and merges into the posterior cingulate. Functionally, the anterior cingulate can be divided into two regions, a rostral affective division and a caudal cognitive division, although recent functional MRI studies suggest even greater functional subdivisions probably exist

(38,

39) . The rostral anterior cingulate receives robust input from the amygdala, whereas the caudal anterior cingulate receives projections from the entorhinal cortex and parahippocampal/hippocampal regions

(40) . Connecting these areas is the cingulum, a fiber tract embedded within the anterior cingulate gyrus and terminating in more rostral prefrontal cortices. Functionally, the anterior cingulate may underlie drive (motivated attention) and concentration (attention allocation), and it may recognize affect-mood conflicts and other processing errors requiring heightened awareness (cognitive and limbic error detection)

(38,

39,

41,

42) . Anterior cingulate lesions interfere with these functions, whereas anterior cingulate hyperactivity has been described in most anxiety disorders, including obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) as well as schizophrenia and chronic pain syndromes

(42) .

Our patient’s clinical and MRI findings strongly suggest the tumor had the greatest effect on the anterior cingulate. Clinically, Jimmy was apathetic and had difficulty sustaining attention, and he often would respond inappropriately to another person’s affect; both of these behavioral deficits are associated with anterior cingulate dysfunction. Multiple MRIs revealed that of all the prefrontal regions, the dysembryoplastic neuroepithelial tumor was closest to the anterior cingulate (approximately 1 mm of separation), necessitating a mid-rostral cingulotomy for surgical access.

Frontal lobe lesions exhibit lateralization with respect to psychiatric or behavioral disturbances. Left hemisphere lesions are more likely to be associated with depression, particularly if the lesion involves the dorsolateral portion of prefrontal cortex. By contrast, right hemisphere lesions are associated with impulsivity and manic behaviors

(3,

4) . Our patient’s dysembryoplastic neuroepithelial tumor was located in the left frontal lobe, but his behaviors were more consistent with right frontal lobe dysfunction, e.g., aggressiveness and disinhibition. This discrepancy could be explained by several neuropsychiatric observations. In children and young adolescents, symptoms of depression can manifest as irritability and psychomotor agitation

(43,

44) . Our patient periodically exhibited these traits, but they were consistently overshadowed by his more extreme behaviors. Another explanation is centered on the observation that dysembryoplastic neuroepithelial tumors can be epileptogenic foci

(10,

11,

13) . Although this patient’s EEG did not show frank epileptic activity, abnormal electrical activity associated with seizures was detected on at least one occasion, and at some point the tumor may have affected the activity of neurons in the left frontal cortex and contributed to his abnormal behaviors.

This case supports other studies demonstrating that neurosurgical cure of a psychiatric disorder is feasible

(45) . Probably the most remarkable aspect of this case is the fact that the worst of our patient’s long-standing conduct disorder traits resolved within hours of neurosurgery. Our patient had a remarkable recovery, but several key issues need to be addressed. The impetus for neurosurgery in our patient was tumor growth, not cure of his behavioral problems. Forecasting neuropsychiatric cure after frontal lobe surgery for tumor removal is difficult at best as differences in tumor size, subtleties in surgical technique, and susceptibilities of different brain regions to operative trauma have left patients like ours with a worsening clinical course, such as postoperative psychosis or epilepsy

(46,

47) . The prognosis is worse when bulky tumors destroy a larger volume of the brain parenchyma, fundamentally altering the neuroanatomical substrates of behavior. Fortunately, our patient’s tumor was relatively small, well circumscribed, and surgically accessible, requiring only partial removal of the overlying anterior cingulate gyrus and cingulum. Partial cingulotomy may have even contributed to our patient’s psychiatric improvement, as several reports have indicated that cingulotomy is an effective treatment for chronic pain, intractable depression, and medication-resistant OCD

(48,

49) .

Pharmacological management of psychiatric illnesses is the cornerstone of modern psychiatry, but this case shows that medication failures may occur in the setting of an underlying brain tumor. Our patient was treated with a number of different medication combinations over the course of 9 years. Both by the patient’s report and according to his mother and professional staff at the residential treatment facility, the side effects of polypharmacy made him very uncomfortable and probably did little to control his extreme behavior. In fact, 3 weeks before surgery, our patient elected to discontinue all psychiatric medications in favor of reduced side effects, yet his behavior did not worsen during that time. These clinical observations suggest that the deleterious effects of the dysembryoplastic neuroepithelial tumor were far beyond the reach of the then-current neuropsychiatric pharmacopeia.