People with intellectual disabilities (ID), defined by an IQ < 70, make up a diverse population characterized by unique healthcare experiences and vulnerabilities (

1). This demographic experiences a myriad of health disparities, including elevated rates of chronic medical conditions (

2,

3), dental diseases (

4), mental illnesses (

5), and premature mortality (

6,

7). Moreover, they encounter significant barriers in accessing healthcare services, which contribute to health disparities and suboptimal health outcomes (

8). Patients with ID often face difficulties in voicing their symptoms or health concerns, making it imperative that healthcare providers adopt specialized patient care approaches (

9). These disparities were exacerbated during the COVID‐19 pandemic, leading to a dramatic increase in patient COVID‐19 mortality among patients with ID compared to the general population (

10).

While medication remains a common therapeutic intervention for this vulnerable population, a half century's worth of research has revealed inappropriate prescribing practices (

11,

12,

13). Specific examples include under prescribing non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory medications (NSAIDs), overprescribing anticholinergic and benzodiazepine medications, and prescription of antiepileptic medications with limited rationale (

14,

15). A particular concern pertains to the prescribing of antipsychotic medications to patients with ID. Antipsychotics are often used off‐label to manage “challenging behaviors” (e.g., aggression, irritability, and self‐destructive behaviors) (

16). While research has demonstrated that individuals with ID experience a higher prevalence of mental health conditions (

3), there are concerns that antipsychotic prescriptions often do not consistently align with DSM‐5 diagnoses (

17,

18). Additionally, patients frequently have limited understanding of their medications beyond basic knowledge of their regimen (

19). Extensive research has documented the adverse effects associated with antipsychotics, such as metabolic side effects and tardive dyskinesia (

20,

21). Although the effectiveness of these medications in managing behavioral issues in patients with ID has remained a long subject of debate (

22), psychiatrists continue to encounter barriers and challenges in limiting the prescription of antipsychotics (

23). While some initiatives, such as the STOMP initiative in England, have been developed to prevent the overprescription of antipsychotics in patients with ID, the United States has not adopted a cohesive policy to address this issue (

24).

Given the potential risks associated with these medications, understanding the factors influencing antipsychotic prescribing practices in this population is crucial. Among these factors, a plethora of literature has found that people with ID who are older, male, of lower socioeconomic status, reside in a group home, have a history of psychiatric hospitalization, or have a co‐occurring mental health diagnosis exhibit a greater prevalence of both appropriate and inappropriate antipsychotic prescriptions (

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33). Some have recognized that the differing prevalence of psychotropic medication is due to the impact of the living environment on varying access to healthcare services (

34,

35). However, there is limited research specifically investigating how living situations alone influence antipsychotic prescribing practices. This study aims to explore whether living environments—such as familial support homes versus group homes—affect both the rates of antipsychotic prescriptions and the classes of medications prescribed, as well as the prevalence of polypharmacy. Addressing this disparity is crucial for refining clinical practices, informing policy decisions, and improving patient outcomes, thus contributing valuable insights to the existing literature.

METHODS

Study Design

Our study was in congruence with a sister study which examined the impact of living situations on healthcare encounters for adults with ID. Further details on methodology, including information on the retrospective chart review process and living situation classification process, are presented elsewhere (

36). Briefly, our study employed a retrospective chart review as its primary research method, analyzing medical records of adult patients from the years 2019 to 2021 (identified via TriNetX [Cambridge, MA, USA]). Inclusion criteria encompassed individuals aged 18 years and older with an ICD‐10 diagnosis of ID. To achieve an appropriate sample size that ensured adequate statistical power while allowing for comprehensive data abstraction, the study adopted a representative approach, selecting 10% of the total population. This process yielded a final sample size of 112 participants. Data abstraction and coding were carried out for living situations. Study data were collected and effectively managed using the Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap [Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN, USA]) application hosted at the study site, in compliance with the methods described by Harris et al. (

37). This study adhered to all necessary ethical and consent protocols, as stipulated by the Institutional Review Board at [Blinded for review] and was granted an exemption.

Chart Abstraction

Two medical students reviewed charts independently for demographic and medical data, including living situation, medication details, and mental health history. Living situation was classified using the following categories: independent, home with biological family (individual resides with parents or siblings), home with other support (individual resides with a consistent caregiver who is not the parent or sibling), group home (support provided by staff who may change), and other (skilled nursing facility, state psychiatric center, shelter, or other facility). Additionally, charts were abstracted for the total number of medications. If the patient was prescribed an antipsychotic, the name and class (typical or atypical) were documented. The presence of a corresponding mental health diagnosis requiring an antipsychotic was verified using ICD‐10 codes for psychotic disorders. We also recorded whether the patient had received mental health services in the past year.

Statistical Analysis

Following chart abstraction, all analyses were conducted using R Version 4.2.1 (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) (

38). Descriptive statistics categorizing sociodemographic factors, level of intellectual disability, living situation, and antipsychotic prescription were calculated for the overall study population. Univariate analyses, which included the Chi‐Square Test of Association for categorical variables and the Kruskal‐Wallis rank sum test for continuous variables, were used to test the association between living situations and the features of interest. In addition, multivariate analysis using multivariable logistic regression was conducted to determine the interaction between living situation and antipsychotic medication prescription while accounting for covariates. Independent analysis was performed by a biostatistician to reduce bias.

RESULTS

Demographics, Living Situation, and Antipsychotic Prevalence

Descriptive statistics in

Table 1 outline findings from 112 adults meeting the study criteria. In general, the mean (SD) age of patients was 39.9 (17.8). Most patients were male (

N = 59, 52.7%) and white (

N = 81, 72.3%). A substantive proportion of patients (

N = 79, 67.9%) were assigned the ICD‐10 code F79, corresponding to an unspecified level of intellectual disability. Most patients lived at home with a biological family (

N = 62, 55.4%), followed by independent (

N = 19, 17.0%), group home (

N = 11, 9.8%), other (

N = 11, 9.8%), home with other support (

N = 6, 5.4%), custodial care (

N = 2, 1.8%), and shelter (

N = 1, 0.9%).

Most patients were prescribed antipsychotics (N = 69, 61.6%), with a minority of patients not prescribed antipsychotics (N = 42, 37.5%). One chart review did not include if the patient was or was not prescribed antipsychotics and was classified as “unknown” (N = 1, 0.9%). Of those prescribed antipsychotics, most were prescribed atypical antipsychotics (N = 36, 85.7%) while some were prescribed typical antipsychotics (N = 6, 14.3%). Half of patients had a mental health diagnosis documented (N = 21, 50%), while half of patients did not (N = 21, 50%).

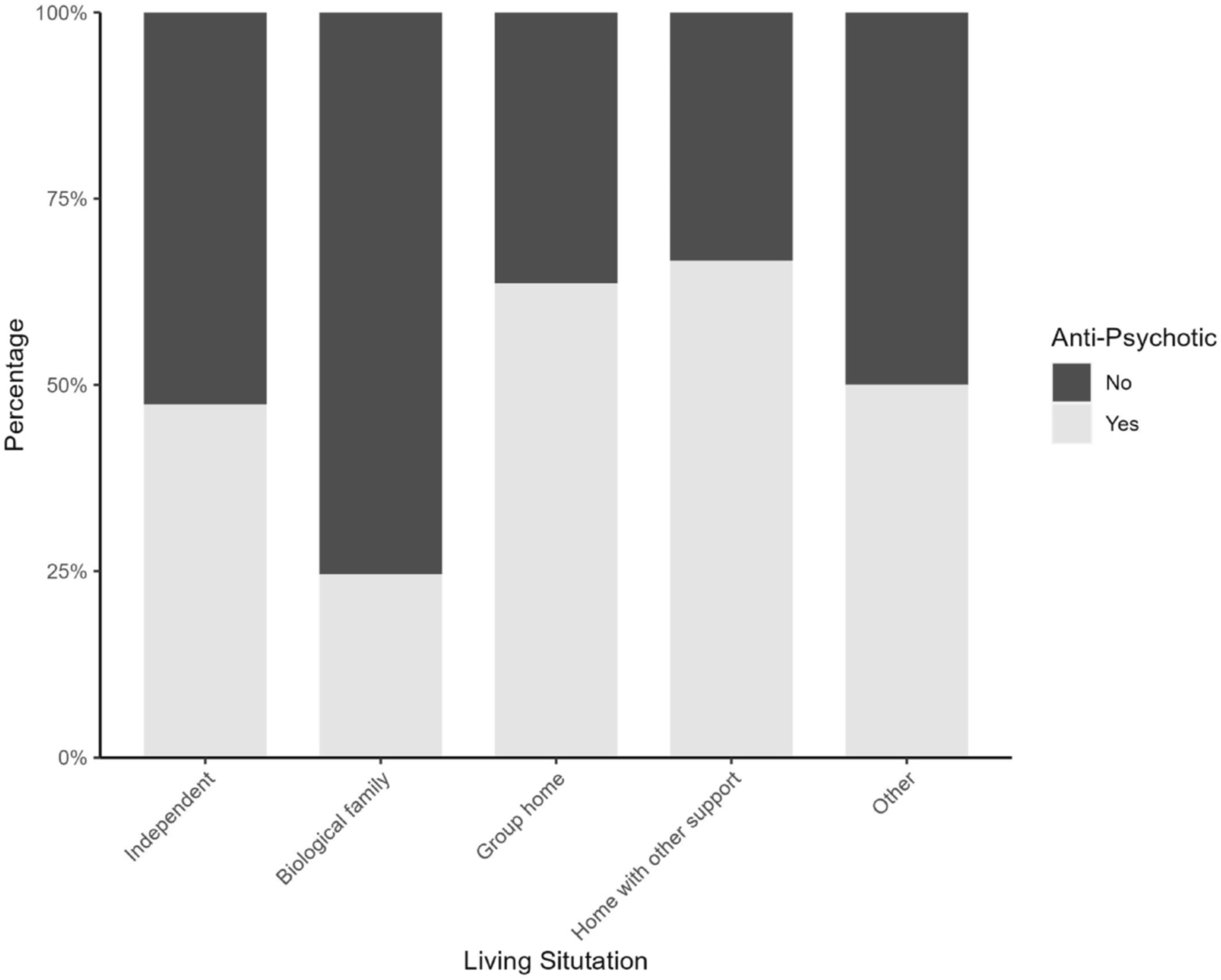

Antipsychotic prescription prevalence varied across living situations, as illustrated in

Figure 1. In general, the largest proportion of patients prescribed antipsychotics lived in non‐familial support homes (

N = 4, 67%) and group homes (

N = 7, 64%), and the lowest proportion of patients prescribed antipsychotics lived with biological families (

N = 15, 25%).

Polypharmacy

Level of polypharmacy is classified as major (>5 medications), moderate (2‐5 medications), and none (<2 medications) (

39). We found that most patients were subject to major polypharmacy (

N = 78, 69.6%), with some patients subject to moderate polypharmacy (

N = 20, 17.9%), and a minority of patients not subject to any polypharmacy (

N = 14, 12.5%). Overall, the median number of prescribed medications was highest for patients living at home with other support (13 medications) and group homes (12 medications), while the median number of prescribed medications was less for patients living with biological families (7 medications).

Univariate Analysis

Living situations were significantly associated with antipsychotic prescriptions (X2 = 11.398, df = 4, p < 0.05). However, no association was found between living situation and antipsychotic class (X2 = 7.2333, df = 4, p > 0.05), living situation and mental health diagnoses (X2 = 7.0921, df = 4, p > 0.05), or living situation and polypharmacy (X2 = 12.048, df = 8, p > 0.05). The median number of prescribed medications did not statistically differ between living situations (Χ2 = 7.8865, df = 4, p > 0.05).

However, the median total medication count was significantly different between anti‐psychotic prescription groups (Χ2 = 19.124, df = 1, p < 0.05), with patients prescribed more medications more likely to be prescribed antipsychotics. Additionally, gender was significantly associated with anti‐psychotic prescription (Χ2 = 10.282, df = 1, p < 0.05). However, other demographic features, including age (p > 0.05), ethnicity (p > 0.05), race (p > 0.05), and level of intellectual disability (p > 0.05), were not significantly associated with antipsychotic prescription.

Multivariate Analysis

To further understand the relationship between living situations and antipsychotic prescribing practices, a multivariable logistic regression model was used (

Table 2). The significant predictor variables were total medication count and gender. In general, the odds of being prescribed an antipsychotic for a male were 4.2 times the odds for a female (OR = 4.207, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.721–10.286). Additionally, for each additional medication prescribed, the odds of being prescribed an antipsychotic increase by 10.1% (OR = 1.101, 95% CI 1.038–1.169). However, the multivariate analysis did not reveal a significant interaction between medications and gender. The living situation categories were not significant in our model either. These results may suggest that living situations are not as significant in predicting antipsychotic prescriptions once other features, such as gender and medication count, are included as covariates.

DISCUSSION

This study offers valuable insights into the prescribing practices of antipsychotics among people with ID, with a particular focus on examining the interplay between living situations, antipsychotic prescriptions, and polypharmacy. First, over half of the individuals in our study were prescribed an antipsychotic. However, of these individuals, only half had a corresponding mental health diagnosis. While these findings are worrying, they align with existing literature that highlights the ongoing trend of prescribing antipsychotics to people with ID irrespective of DSM‐V diagnoses (

18), suggesting that healthcare providers may still be inappropriately using antipsychotics to manage “challenging behaviors,” despite their limited efficacy (

16). As described in Flood, these findings emphasize the ongoing conversations in which physicians and pharmacists bear the responsibility of thoroughly assessing the potential benefits of medication for people with ID, ensuring both its appropriateness before prescription and the realization of anticipated benefits thereafter (

40).

The relationship between living situations and antipsychotic prescriptions found in our study varied with the existing pool of literature and is therefore worth mentioning. Previous studies have indicated that residing in group homes or other residential settings heightens the probability of being prescribed antipsychotic medications (

27,

28,

30,

31). Lunsky and Modi attributed this disparity to the possibility that the threshold for prescribing multiple medications may be lower for individuals in these settings. This could be because they exhibit more severe psychiatric symptoms, which may not respond as effectively to monotherapy, rather than having a greater number of psychiatric diagnoses. While our univariate analysis revealed that individuals living in group homes and those residing in homes with other forms of support were more likely to be prescribed antipsychotic medications, our multivariate analysis showed there was no statistical significance between living situation and antipsychotic prescription when accounting for covariates including gender and total medications prescribed. Still, it is plausible that living situations may still be significant with a larger sample size.

Interestingly, age was not associated with antipsychotic prescriptions, which differed from Bowring et al. and Sheehan's studies which both found associations between older age and psychotropic medication (

26,

41). Regardless, our study supported prior findings which found male gender and total number of medications were significant predictors in being prescribed antipsychotic medication (

42). Past research has attributed the gender disparity in antipsychotic prescription amongst people with ID to increased instances of males with ID exhibiting “challenging behaviors” (

28). However, literature has shown that males are more likely to be prescribed antipsychotic medications in the general population as well, suggesting that other dynamics may be at play (

29,

43). Regarding the total number of medications, it is logical that a higher number of medications would be associated with an increased likelihood of antipsychotic prescription, as demonstrated in prior research regarding patients with ID and polypharmacy (

14). While our study did not identify a significant difference in the number of prescribed medications based on living situations, polypharmacy was prevalent in our study and remains a concern in the management of individuals with ID. Healthcare providers must stay vigilant, and future policy and practice should incorporate regular audits, annual health checks, and standardized medication reconciliation.

Our study had some limitations which warrant mention. First, the retrospective nature and the relatively small sample size of our study, as mentioned above, may affect generalizability. Second, our study design assumed living situation and prevalence of antipsychotic prescription were two distinct variables. In reality, there is a complex interplay between the two, as patients with more physical and mental health problems are less likely to reside in independent living situations and vice versa. Thus, any conclusions from our results should be examined within this context. Third, our chart abstraction tool relied solely on demographic information (e.g., emergency contact phone numbers) present in the electronic medical record (EMR) to assess living situation, potentially leading to error. Additionally, the use of ICD‐10 codes for classification posed challenges, as a significant proportion of participants were diagnosed with an unspecified level of intellectual disability. This reflects the limitations of ICD‐10 codes, which can be subjective and influenced by varying levels of clinician training. Many clinicians may not be adequately trained to accurately identify and classify the precise level of intellectual disability. Fourth, our study did not account for dosage, an important factor since off‐label use of antipsychotics often involves varying dosages. The lack of dosage documentation is a notable limitation that may have influenced our outcomes. Similarly, inconsistencies and inaccuracies within the EMR (e.g., outdated medication lists) may have impacted our data as well.

Another inherent limitation is the generalizability of the research to individuals with ID in other contexts. The study was conducted in Pennsylvania, where support services are organized through a blend of community‐based programs and institutional care. This reflects a regional model that may differ significantly from practices in other parts of the United States or internationally. Community‐based services in Pennsylvania typically focus on integrating individuals into local settings, while institutional care is provided for those with more complex needs. Due to these regional variations in service provision, the applicability of our findings to other settings with different support structures may be limited.

Despite these limitations, our study is the only one to our knowledge to solely explore the impact of living situations and antipsychotic prescribing practices in adults with ID in the United States. Further research exploring the underlying factors driving prescription patterns is essential for advancing our understanding of ID healthcare provision and optimizing patient outcomes.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, our study highlights a significant association between living situation and antipsychotic prescriptions, particularly noting that patients in non‐familial support homes and group homes are more likely to receive antipsychotics compared to those living with biological families. However, no significant associations were found between living situation and other variables, including antipsychotic class, mental health diagnoses, or polypharmacy. Moreover, the multivariate logistic regression analysis identified gender as a significant predictor, with males exhibiting a higher likelihood of being prescribed antipsychotics compared to females. Additionally, the total medication count was positively correlated with antipsychotic prescription, suggesting that patients with more complex medication regimens are more likely to receive antipsychotics. Interestingly, living situation did not emerge as a significant predictor in the multivariate model, underscoring the dominant influence of gender and medication count on prescribing decisions. Further research is needed to uncover the underlying factors behind these prescription patterns.