Panic disorder and anxiety symptoms are hypothesized risk factors for suicidal behavior. However, studies of the relationship of suicidal acts to anxiety in either the presence or absence of major depression have yielded conflicting results.

Some studies have indicated that patients with panic disorder have the same rates of suicide as patients with major depression

(1,

2). Others have shown a lower incidence of suicide in “pure” panic disorder

(3–

5). One reason for the discrepancy among results in the literature may lie in the failure of studies with smaller, convenience samples to take into account other factors that predispose patients to suicidal behavior. Such factors include comorbid mood disorders, traits of aggressivity and impulsivity, a family history of suicidal acts, and comorbid substance abuse or alcoholism. For example, in a study of patients with panic disorder

(6), patients with a history of depression had a higher rate of attempted suicide than the patients without depression (70.6% versus 29.4%). However, this study did not evaluate other putative risk factors, such as axis II disorders and lifetime traits such as aggression and impulsivity.

Results

Of the total subjects, 143 (52.6%) had attempted suicide and 129 (47.4%) had not. The two subgroups did not differ on demographic characteristics (data available on request). The mean age of the entire study group was 35.2 years (SD=11.7); 42.6% were male (N=116), and 77.9% were Caucasian (N=212).

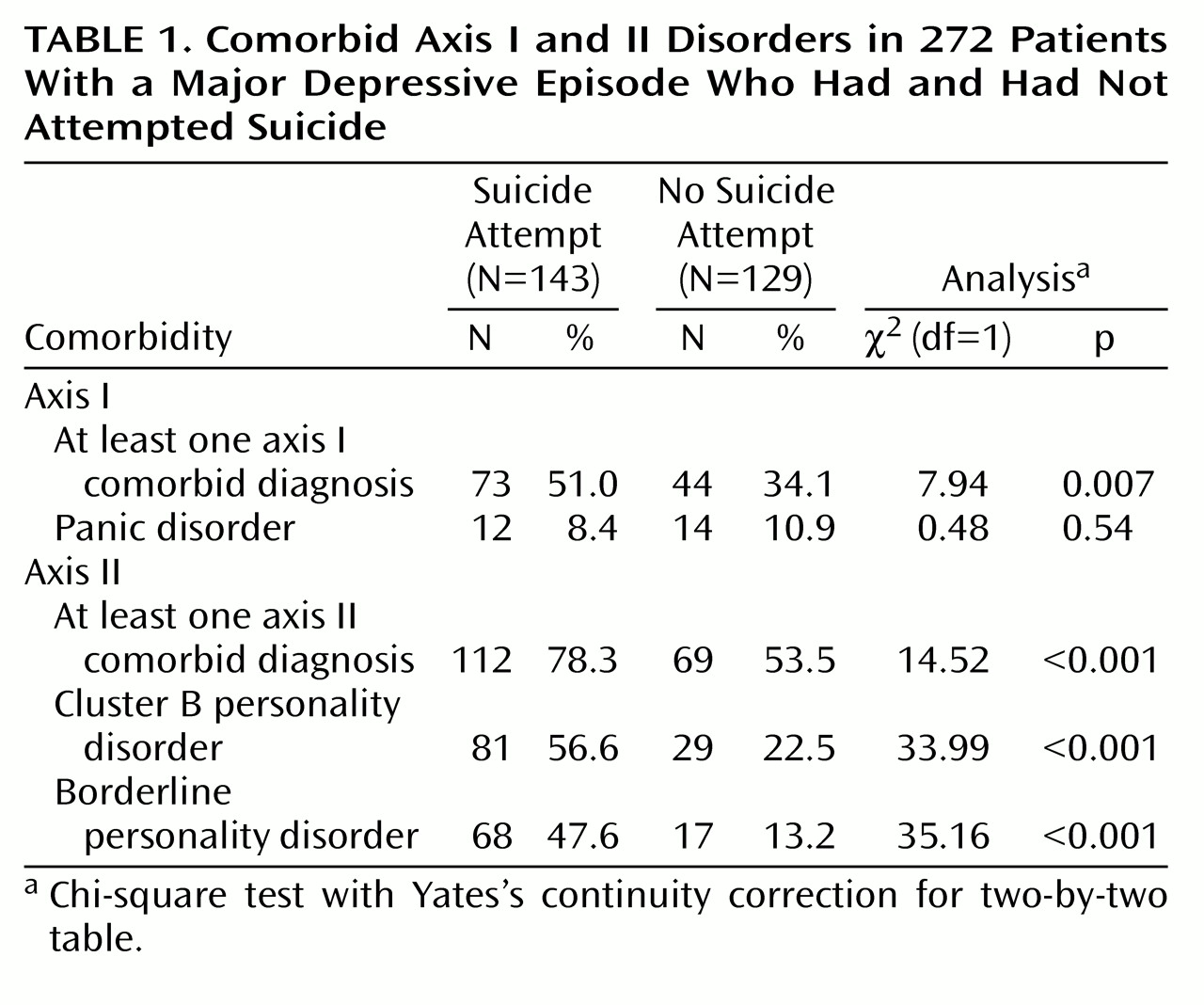

One-third of the subjects (34.2%, N=93)—more than one-half of the attempter group—had made multiple suicide attempts. At least one comorbid diagnosis was identified in 42.6% of the study group (N=116). The suicide attempters and nonattempters differed significantly in the numbers with axis I and axis II comorbid disorders; both were more common among the attempters (

Table 1).

Panic disorder was present in 26 subjects (9.6%; four men and 22 women). The attempters did not differ significantly from the nonattempters in lifetime rate of panic disorder (

Table 1).

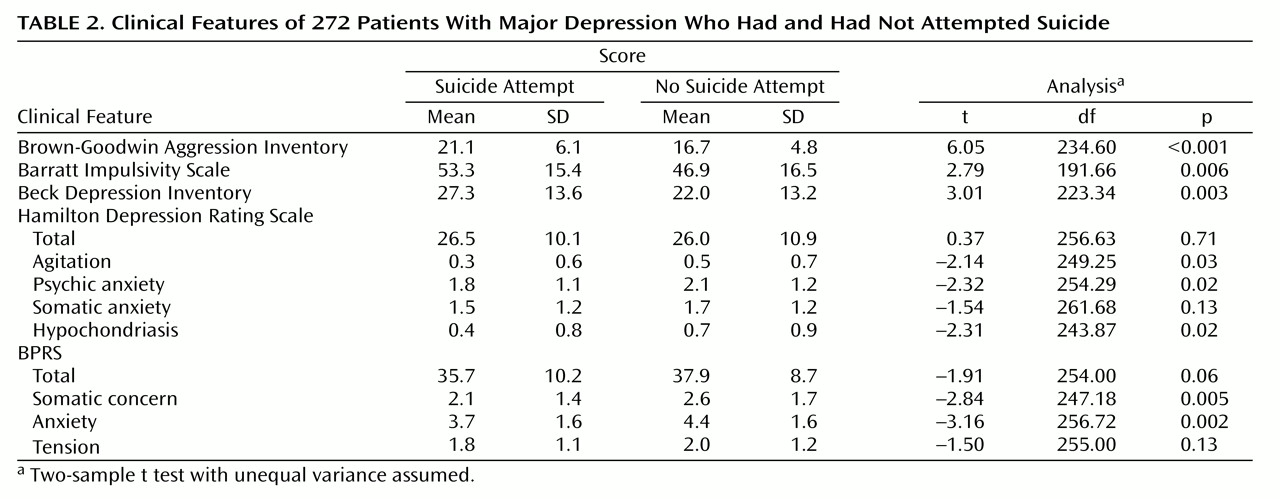

The attempters scored higher on subjective depression (Beck Depression Inventory) than the nonattempters, but they did not differ in severity of objective depression (Hamilton depression scale total) or general psychopathology (BPRS total) (

Table 2).

The mean score for anxiety items on the Hamilton depression scale was higher in the nonattempter group, and there were significant differences for agitation, psychic anxiety, and hypochondriasis (

Table 2). The BPRS mean score for anxiety was also higher in the nonattempter group, and there were significant differences for the somatic concern and anxiety items (

Table 2). A Hotelling T

2 test multivariate comparison of the attempters and nonattempters indicated significant differences between groups for the Hamilton scale anxiety symptoms (F=2.78, df=4, 260, p=0.03), the BPRS anxiety symptoms (F=5.03, df=3, 255, p=0.002), and the Brown-Goodwin Aggression Scale and Beck Depression Inventory scores (F=18.70, df=2, 202, p=0.001). Thus, the mean scores for anxiety and the combination of aggressivity and subjective depression were significantly different in the attempters and nonattempters (also see

Table 2).

After adjustment for panic disorder and anxiety measures, a logistic regression of suicide attempter status on aggressivity showed that aggressivity was still highly predictive of attempter status (likelihood ratio test: χ2=28.71, df=1, p<0.001). Using a likelihood ratio test based on a logistic regression, we found that panic disorder and anxiety measures together, with adjustment for aggression, were significant predictors of attempter status (likelihood ratio test: χ2=30.70, df=16, p=0.001). But it was higher anxiety in the nonattempters that explained the finding.

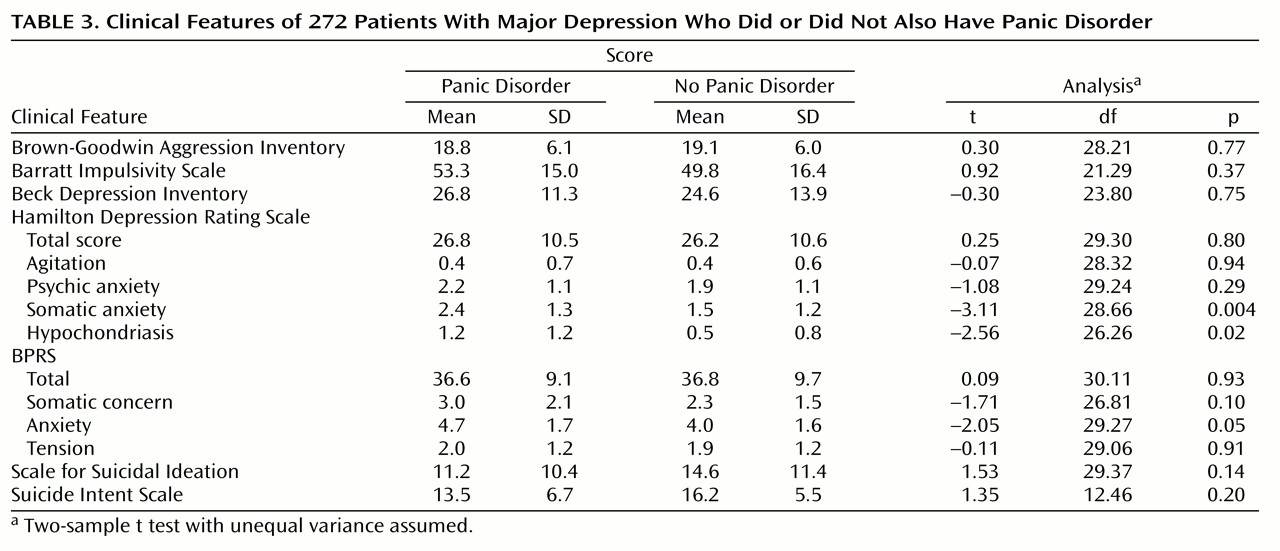

The patients with panic disorder had higher mean scores on the somatic anxiety and hypochondriasis items of the Hamilton depression scale than the patients without panic disorder (

Table 3). The patients with panic disorder did not significantly differ from those without panic disorder on the measures of aggression and impulsivity or on the total scores on the Hamilton depression scale, BPRS, or Beck Depression Inventory (

Table 3). There was also no difference in lethality scores between the patients with and without panic disorder. No significant correlation between anxiety measures and lethality was found.

Discussion

The major results of this study are that a lifetime history of a suicide attempt in patients with a major depressive episode is unrelated to a history of panic disorder and is associated with less severe symptoms of agitation and anxiety.

To our knowledge, only one previous study

(17) compared the incidence of suicide attempts among depressed patients with and without panic disorder. In that study there was a higher frequency of suicide attempts in patients with infrequent panic attacks than in those with panic disorder or with depression only. In 47% of the subjects the panic attacks began after the suicide attempt or were not present at the moment of the attempt. Thus, that study did not suggest that panic attacks directly increased the risk of suicide attempt. Female gender and a history of psychosis, but not panic attack history, significantly related to a history of suicidal behavior.

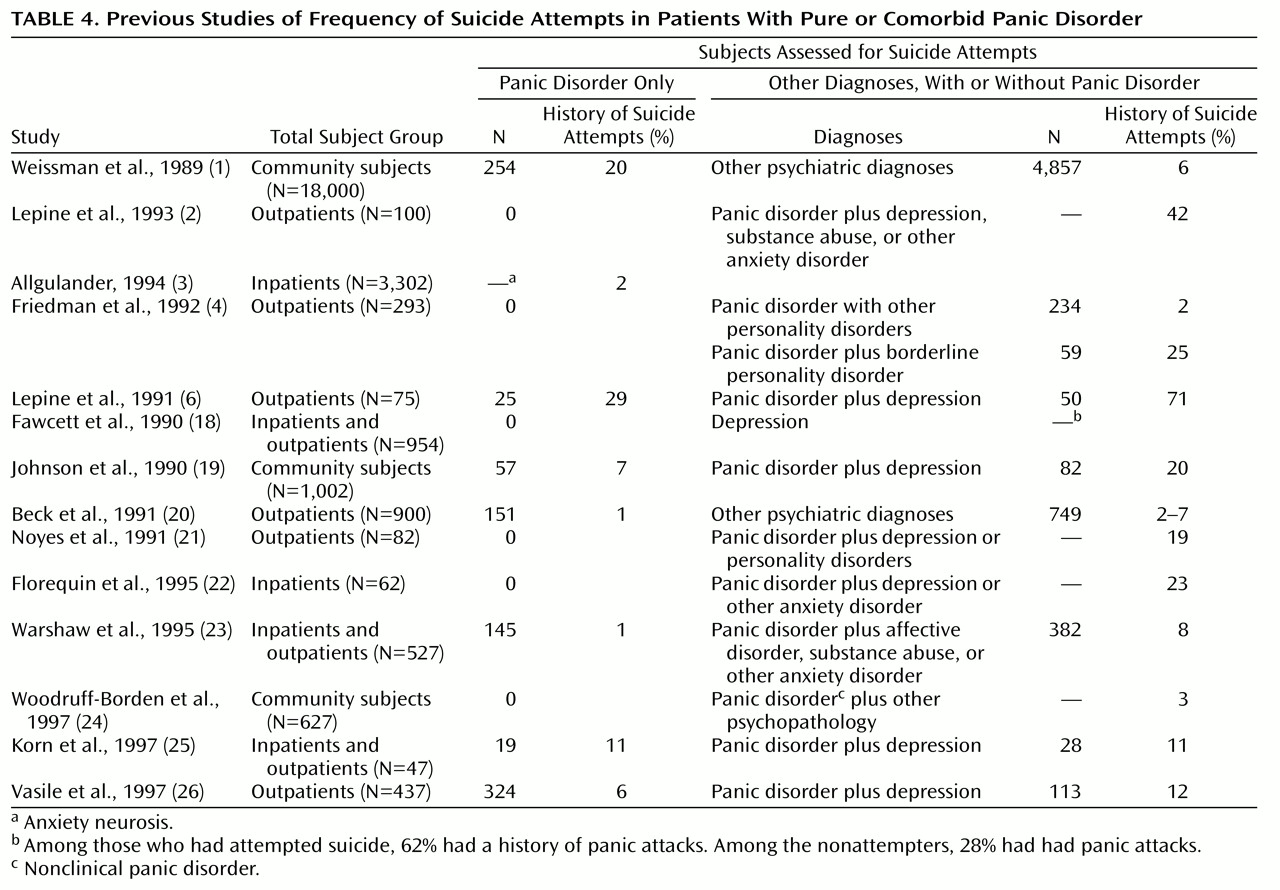

Other investigators (

Table 4) studied patients with panic disorder and patients with comorbid panic disorder, reporting an incidence of suicide attempts from 1% to 29% in the patients with panic disorder alone (mean=9.6, median=6.5) and from 2% to 71% in the patients with comorbid panic disorder (mean=19.1, median=12.0). The variance of the values and the fact that the group with comorbid conditions had a median rate double that of the group with panic disorder alone suggest that comorbidity is an important factor in suicidal acts. The rate of suicide attempts in panic disorder alone may still be higher than in the general population.

Investigators in three studies

(2,

21,

24) calculated the incidence of suicide attempts in a population of comorbid panic disorder patients, reporting rates of 42%, 19%, and 3%. The percentage of suicide attempters in our group of patients with comorbid panic disorder was 53.3%. Such different rates suggest that a major reason for variance in suicidal behavior is related to factors other than comorbid panic disorder. This conclusion is consistent with the report by Beck et al.

(20) of a higher rate of suicide attempts in patients with a primary mood disorder and secondary panic disorder than in subjects with panic disorder and secondary mood disorder.

Borderline personality disorder and the traits of aggression and impulsivity have been found to be associated with suicide. In our study group, we found a significantly higher rate of borderline personality disorder in attempters than in nonattempters (27.2% versus 6.7%, respectively). Similarly, Friedman et al.

(4) reported that the lifetime prevalence of suicide attempts in a group of patients with borderline personality disorder and panic disorder was 25%, compared with 2% in patients with panic disorder only. Noyes et al.

(21), in a 7-year follow-up study of patients with panic disorder, found completed suicide only in panic disorder patients with comorbid severe depression or personality disorder. This suggests that suicide is not related to panic disorder alone, a possibility that is consistent with our results.

Levels of aggression and impulsivity correlate with past suicidal behavior

(7), but few studies have examined the relationship of aggression, impulsivity, and anxiety symptoms. We previously reported

(7) that suicide attempters have more lifetime aggression and impulsivity than nonattempters and that aggression is greater in patients with cluster B personality disorder diagnoses. In this study, the relationship of aggression and impulsivity to history of suicidal acts was independent of the presence of anxiety symptoms or panic disorder (

Table 2). Thus, aggression and impulsivity should be assessed in studying suicidal behavior in order to avoid confounding results.

We found that nonattempters had significantly higher scores on the Hamilton and BPRS anxiety items than attempters. A study of anxiety measures in suicidal adolescents

(27) showed higher state and trait anxiety levels in attempters than in nonattempters. The disagreement between these results and ours could be partially explained by differences between subject groups.

In a group of adults, Fawcett et al.

(18) found a higher rate of psychic anxiety in patients with acute suicide risk (suicide in less than 1 year from the time of interview); however, the suicidal patients had higher alcohol abuse ratings than the comparison groups. The link between suicidal behavior and anxiety symptoms observed by some authors could be explained by the presence of substance abuse in patients with high anxiety levels.

In our study group, greater anxiety was present in the nonattempters. Anxiety may be protective if it is associated with fear of death or illnesses. These results need confirmation because the implications for the use of antianxiety medications in patients with major depression and anxiety symptoms are profound. Such agents may increase the risk of suicide attempts and suicide. In a Swedish study

(28) it was found that many depressed persons who committed suicide had received anxiolytics instead of antidepressants shortly before death. Perhaps their physicians were responding to the anxiety symptoms of depression, thereby not only failing to treat the depression but possibly facilitating suicide by reducing anxiety.

Our study has the following limitations. Because our study group included only inpatients, the severity of psychopathology was not representative of the general population. Furthermore, although we did not find a relationship between a history of panic disorder and suicide attempts, we did not have information about the relationship between onset of panic disorder and suicide attempts. In addition, we based our analyses on seven anxiety items from the Hamilton depression scale and BPRS, rather than from a scale specifically designed to measure anxiety.

In conclusion, the presence of panic disorder in the context of a major depressive episode does not seem to be associated with an increased risk of suicidal behavior in this inpatient population. Furthermore, higher levels of anxiety, agitation, and hypochondriasis appear to represent putative protective factors for suicidal behavior among such patients. We could infer that anxiety might restrain patients with suicidal ideation from acting on their suicidal impulses. However, sufficiently severe suicidal ideation and hopelessness, combined with impulsivity, could override anxiety and lead the patient to attempt suicide.