Borderline personality disorder was first distinguished from the broader construct of borderline personality by Spitzer et al.

(1), who clarified what soon after became DSM-III criteria. Recognizing that the term “borderline” had been used as an adjective to modify a large number of terms (including “condition,” “syndrome,” “personality,” “state,” “character,” “pattern,” “organization,” and “schizophrenia”), the Spitzer group distilled the range of uses into the two major ways that the term had been used most often. The first referred to “a constellation of relatively enduring personality features of instability and vulnerability with important treatment and outcome correlates”

(1, p. 17). This conceptualization was consistent with the work of Gunderson and Singer

(2), among others, and became the basis for DSM-III borderline personality disorder.

More recently, Fossati et al.

(11) tested whether borderline personality disorder is a unitary construct using confirmatory factor analysis on DSM-IV borderline personality disorder criteria in a study group that included both inpatients and outpatients. In contrast to the two earlier factor analytic studies of borderline personality disorder criteria

(6,

10), the analysis by Fossati et al., who used the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Personality Disorders, was generally consistent with the concept that borderline personality disorder reflects a unidimensional construct. Although Fossati et al. observed some variability from the rank ordering of borderline personality disorder criteria as listed by DSM-IV, their results were reasonably parsimonious with the borderline personality disorder category. Nonetheless, they correctly noted that “diagnostic homogeneity does not imply the absence of natural subgroups” of patients with borderline personality disorder

(11, p. 77). Indeed, there were hints of a possible dimensional gradient involving impulsivity and anger dyscontrol apart from the borderline personality disorder categorical construct.

Results

Sixty-two (44%) of the 141 participants met criteria for borderline personality disorder.

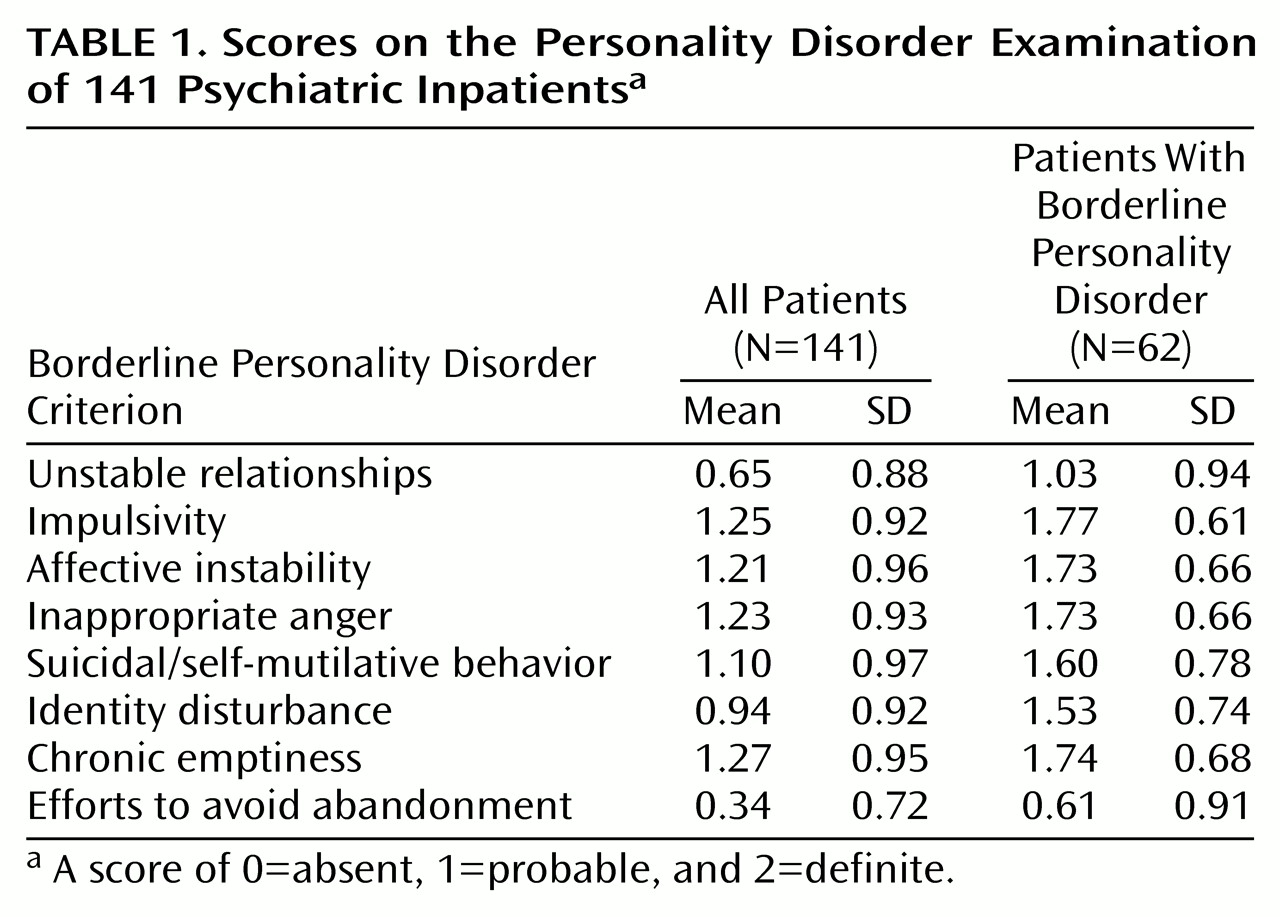

Table 1 shows the mean scores on the Personality Disorder Examination of all patients as well as those who met criteria for borderline personality disorder. Noteworthy is the low rate of endorsement for the criterion of efforts to avoid abandonment. Cronbach’s alpha

(18) for the borderline personality disorder criteria set was 0.69, suggesting adequate internal consistency.

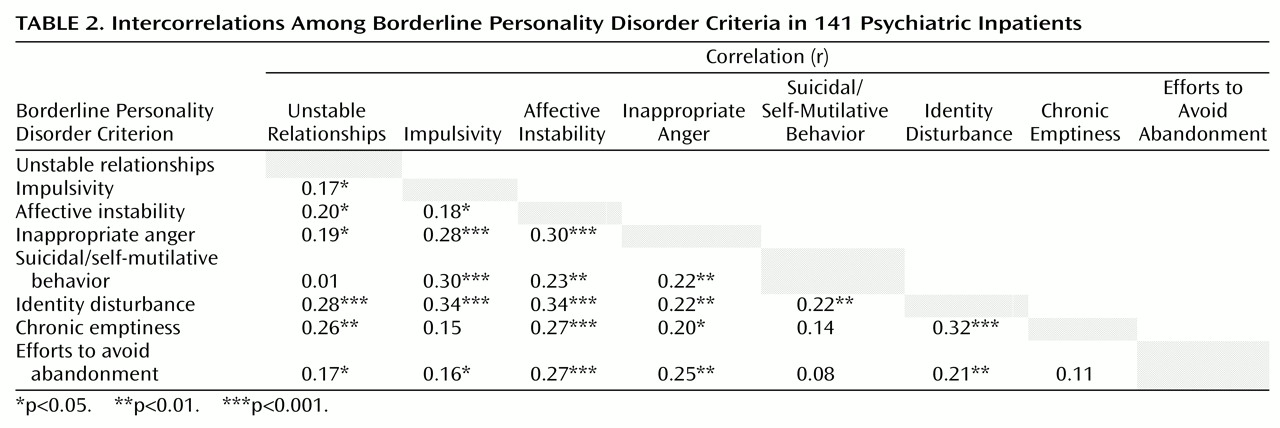

Table 2 shows the intercorrelations among the borderline personality disorder criteria. Overall, the internal consistency of the criteria was further supported by the strength of the relationships among the items. Of note, affective instability and identity disturbance were significantly correlated with the entire set of borderline personality disorder criteria.

A principal components factor analysis

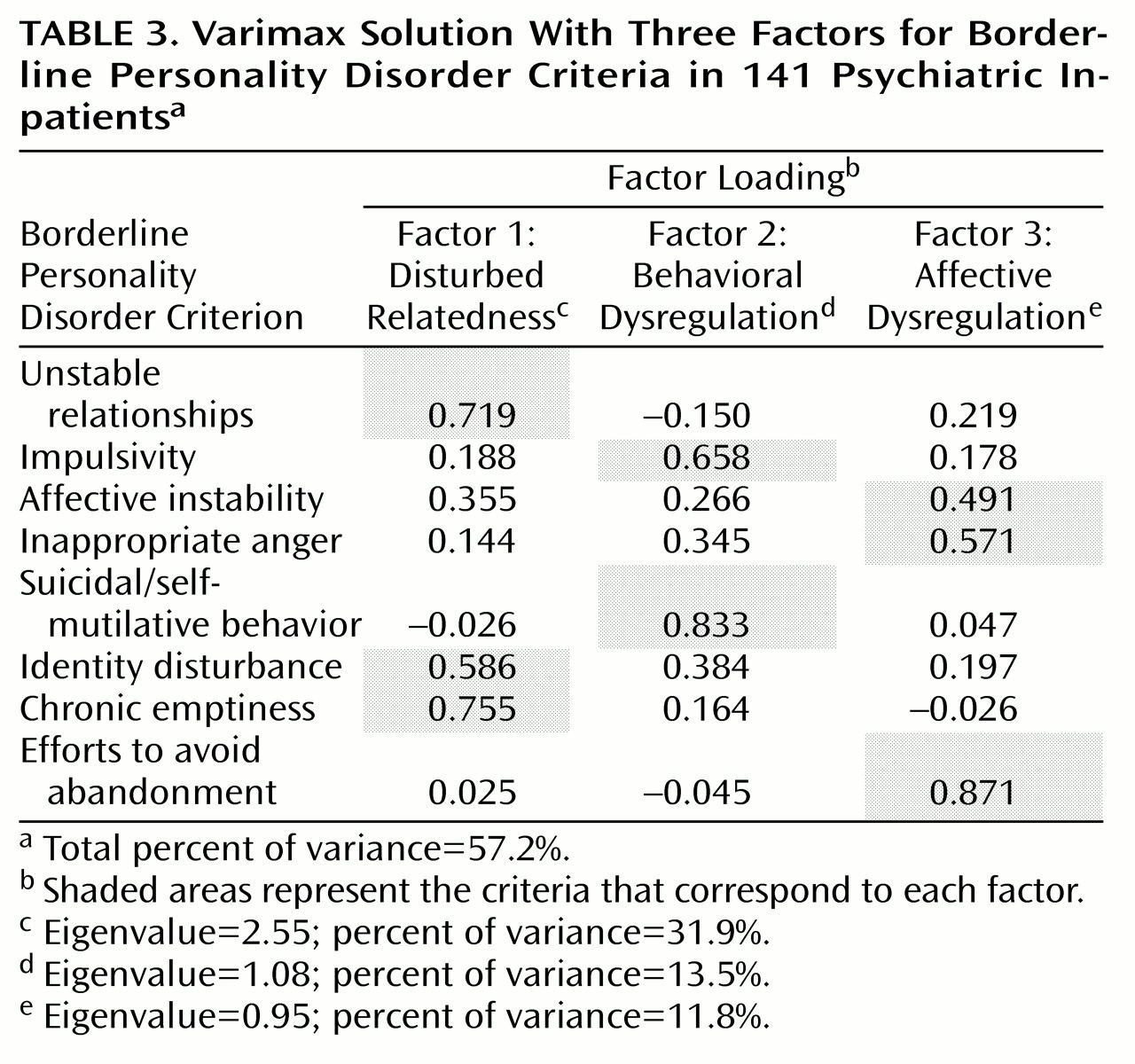

(19) was conducted on all of the borderline personality disorder criteria. The results of this analysis indicated that the most appropriate solution involved three factors. A varimax (orthogonal) rotation specifying a three-factor solution accounted for 57.2% of the variance. We repeated the analyses using principal-axis factoring, and the two solutions were nearly identical (Tucker’s coefficient of congruence [20] ranged from 0.97 to 0.99 for the three factors).

Table 3 summarizes the results from the varimax rotation for the three-factor solution. The first factor, disturbed relatedness, consisted of the unstable relationships, identity disturbance, and chronic emptiness criteria. The second factor, behavioral dysregulation, consisted of the impulsivity and suicidal/self-mutilative behavior criteria. The third factor, affective dysregulation, consisted of the affective instability, inappropriate anger, and efforts to avoid abandonment criteria.

The relative magnitude of the contribution made by each factor to explaining the presence of borderline personality disorder was also examined. Effect sizes

(21) were computed by using the F value for factor scores pertaining to each factor to independently predict group membership (absent, probable, or definite borderline personality disorder diagnosis). All of the effect sizes were large in magnitude, ranging from 0.74 to 0.88.

Discussion

Using a reliably administered diagnostic instrument, we conducted a factor study of the DSM-III-R borderline personality disorder criteria in a group of young adult psychiatric inpatients. Overall, borderline personality disorder items appeared to demonstrate adequate internal consistency, as suggested by the criteria intercorrelations and by a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.69. Two criteria, affective instability and identity disturbance, were significantly correlated with the entire borderline personality disorder criteria set, suggesting that these two items are core features of the disorder in this study group. In an exploratory factor analysis of the items, a three-factor solution appeared most appropriate, both empirically (i.e., on the basis of the interpretation of the principal components analysis) and theoretically (i.e., on the basis of the conceptual quality of the factors). The three-factor model accounted for 57.2% of the variance, and effect sizes based on the variance in the borderline personality disorder diagnosis explained by the factors were all large in magnitude, suggesting that each represents an important component of the disorder.

The three identified factors hold conceptual appeal. The first factor, disturbed relatedness, consists of the criteria of unstable relationships, identity disturbance, and chronic emptiness. This factor reflects a deficit in the sense of self and inability to relate to others, something that might have been historically termed “anaclitic.” In many ways, this factor can be viewed as a core personality aspect of borderline personality disorder in that the disturbed and incomplete sense of self is an underpinning of much of the symptomatic interpersonal behavior seen in individuals with the diagnosis of borderline personality disorder. In addition, identity disturbance was correlated with the remaining borderline personality disorder criteria (

Table 2).

The second factor, behavioral dysregulation, consists of the impulsivity and suicidality/self-mutilative behavior criteria. This factor captures the most treatment-relevant symptomatic behavior of an individual with borderline personality disorder. It is different from the other factors and criteria in the sense that these are behaviors as opposed to symptoms, character traits, or temperaments. For our group of acutely disturbed psychiatric inpatients, in all likelihood these are the criteria that called attention to the disorder and led to hospitalization.

The third factor, affective dysregulation, consists of the criteria of affective instability, inappropriate anger, and efforts to avoid abandonment. This factor might reflect the hypothesized physiological temperament of borderline personality disorder

(22,

23) or, more specifically, may express how effectively individuals with core borderline personality disorder moderate their response to stress. At first blush, the finding that efforts to avoid abandonment loads heavily on this factor might appear to be an anomaly; however, one can imagine that abandonment concerns plus poor affective dysregulation may translate directly into typical “borderline” behavioral manifestations (for example, refusing to leave a therapist’s office—an event with typically highly charged affect). On the other hand, this finding could be a statistical artifact of the low base rate of endorsement of this item (

Table 1) and therefore specific to our study group.

Rosenberger and Miller’s factor analysis of DSM-III borderline personality disorder with college undergraduates

(6) produced two factors. One factor consisted of the identity disturbance, efforts to avoid abandonment, emptiness, and unstable relationships criteria. The second factor consisted of the affective instability, impulsivity, self-damaging acts, and inappropriate anger criteria. In contrast, the results from the present study appear to parse out the impulsive behavior criteria from the unstable affect criteria. The criteria that make up our behavioral dysregulation factor are qualitatively different from other borderline personality disorder criteria in that they reflect symptomatic behaviors as opposed to symptoms, temperaments, or traits. In fact, the behavioral dysregulation factor may involve the most pernicious (and potentially lethal) criteria for the clinician to consider when treating a patient with borderline personality disorder

(24). The independence of this factor is also consistent with results from the longitudinal stability study of borderline personality disorder criteria conducted by Links et al.

(25), who demonstrated the stability of the borderline personality disorder impulsiveness criterion, suggesting that it is a key feature of borderline personality disorder. Links et al. also pointed out that targeting the impulsive behaviors may be the best way to have a positive impact on the prognosis of the disorder.

The factor analysis of DSM-III-R borderline personality disorder criteria in female inpatients by Clarkin et al.

(10) identified three factors. The first factor consisted of emptiness/boredom, identity disturbance, efforts to avoid abandonment, and unstable relationships. Unstable relationships also loaded to a smaller degree on the second factor, along with suicidality, anger, and labile affect. Their third factor consisted of the impulsivity criterion alone, although labile affect loaded negatively on this factor. In contrast, our results appear to be divided more into factors broadly reflecting personality, behavior, and affect. Perhaps this derives from our more heterogeneous study group, which included both men and women and patients with and without borderline personality disorder, thus providing a broader range of phenomenological variation.

The study by Fossati et al.

(11) tested the DSM-IV borderline personality disorder as a diagnostic category. Their main results were supportive of ours, although exploratory latent class analyses suggested a dimensional subcategory of inappropriate anger and impulsivity. This dimension appears related to our second factor of behavioral dysregulation insofar as they share elements of impulsivity and aggression. In our patients the aggression appears to be expressed in self-directed form (suicidal/self-mutilative), and in the study group of Fossati et al. it appears more generic (inappropriate anger).

Our study has certain strengths and limitations. Our borderline personality disorder symptom data were obtained by means of the reliable use of the Personality Disorder Examination

(14) by highly trained and monitored clinicians. Our results were based on DSM-III-R, however, and thus have limited applicability to DSM-IV; it will be important to determine if the same patterning of components holds for the DSM-IV borderline personality disorder diagnosis in future studies. Although the fact that our patients were acutely ill may influence the endorsement of criteria and the assignment of diagnosis of personality disorders

(26), the conservative duration criterion specified by the Personality Disorder Examination

(14) may have minimized such state-trait artifacts

(27). In addition, our assessment procedures were implemented a few weeks after admission, thus eliminating acute decompensation and the potential effects of substance withdrawal. Because our study group was composed of acutely ill psychiatric patients requiring inpatient level treatment, our findings may not be generalizable to outpatients or community samples.

To summarize, our exploratory factor analysis suggests that there may be homogeneous domains of borderline personality disorder criteria and that some of these domains reflect symptoms, others reflect traits, and still others reflect symptomatic behaviors

(28). These findings may help to outline central components of the disorder and can also inform treatment plans by identifying subsets of criteria that may be more or less responsive to different treatment interventions. For instance, treatment plans may specify medication to target the affective dysregulation factor, cognitive behavior treatment could be used to target the behavioral dysregulation factor, and longer-term psychotherapy may be necessary for the disturbed relatedness factor.

Our factor model should be tested in another group of subjects by using confirmatory factor analysis with particular attention paid to the class of criteria (e.g., behavioral, temperament, personality). Additional tests of factor analytic models are also needed in more broadly based groups of subjects. Finally, temporal stability of the factors should be examined in longitudinal studies. It may be that some factors are stable (such as our disturbed relatedness and affective dysregulation factors) but that others appear only when an individual is severely stressed (such as our behavioral dysregulation factor).