The neuropsychology of late-life depression is poorly understood. Despite numerous studies that have described cognitive functioning in late-life depression, only a few have employed a comprehensive assessment of cognitive domains

(1–

4). Hart et al. found impairment on measures of word generation, visuoconstruction, short-term memory, and psychomotor speed

(2). Boone et al. found deficits in the visuospatial domain and in visual memory, executive functioning, and information processing speed

(1); moreover, the level of executive dysfunction was related to severity of depression. Lesser et al.

(4) found that older depressed subjects exhibited numerous visuospatial deficits. A more important finding was that elders with late-onset depression had additional executive function impairment that was not seen in those with early-onset depression. A study by Palmer et al.

(3) found that late-life depression subjects with primarily neurovegetative symptoms had visuospatial and executive function deficits when compared to both late-life depression subjects with primarily depressed mood and elderly nondepressed subjects.

In sum, the findings across studies that employed comprehensive neuropsychological batteries have varied somewhat but suggest that a substantial proportion of elderly individuals with depression exhibit concurrent cognitive impairment, particularly in visuospatial ability, psychomotor speed, and executive functioning. Moreover, executive deficits in particular may be strongly associated with late-onset depression and vegetative symptoms.

While our understanding of the relationship between particular clinical characteristics of depression and cognitive functioning is increasing, little is known about the cognitive response to treatment of geriatric depression. A critical issue to determine is whether cognitive functioning improves following successful treatment of late-life depressive episodes. One group of investigators studied elderly medical-psychiatric inpatients, many of whom had treatment-resistant depression, before and after receiving treatment with either a tricyclic antidepressant or ECT

(5). Cognition, as measured by the Mattis Dementia Rating Scale, was generally stable among those patients with normal pretreatment cognitive functioning. However, a substantial number of patients with impaired cognitive functioning before treatment improved following treatment.

The present study investigated the specific cognitive effects of successful depression treatment in a group of elderly psychiatric patients with major depression. We predicted that among those subjects who responded to treatment, there would be a general, mild improvement in cognitive functioning. Among those with no cognitive impairment before treatment, we expected that minimal change would be detected by our screening measures, which are relatively insensitive to small changes in individuals with normal cognition. On the basis of findings from structural and functional imaging studies, as well as cognitive evidence that the basal ganglia/frontal lobe circuitry plays a critical role in late-life depression, we further hypothesized that among elderly depressed patients with cognitive impairment before treatment, specific improvement would be seen in executive functions, while other cognitive domains would remain stable.

Method

Subjects

We studied 62 elderly patients who met DSM-IV criteria for major depression and 20 elderly comparison subjects recruited from local advertisements. Patients were recruited between June 1996 and December 1998 from in- and outpatient geriatric units of the Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic, a teaching hospital that provides psychiatric care to a large urban and rural catchment area in Southwestern Pennsylvania. All patients were enrolled in an intervention study in which each was initially randomly assigned, under double-blind conditions, to treatment with either the tricyclic agent nortriptyline or the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor paroxetine. Although some cognitive impairment was present in some patients, none met Alzheimer’s disease diagnostic criteria

(6) or DSM-IV criteria for dementia. After complete description of the study to the subjects, written informed consent was obtained.

Measures

Data were derived from assessments performed by the staff of the Mental Health Intervention Research Center for the Study of Late-Life Mood Disorders at the University of Pittsburgh. Subjects who participate in the Center’s treatment protocols undergo medical, psychiatric, and neuropsychological assessments at baseline and at yearly follow-up sessions. For this study, an additional brief screening of neuropsychological function was administered to patients who responded to treatment 12 weeks after the baseline assessment to assess short-term cognitive changes related to treatment for depression.

The analyses focused on a subset of cognitive and psychosocial instruments, including the 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale

(7), the Global Assessment of Functioning Scale

(8), the Mini-Mental State

(9,

10), and the Mattis Dementia Rating Scale

(11,

12). The Hamilton depression scale is a widely used, interviewer-administered rating scale for depressive symptoms that has been validated in older patients with and without cognitive impairment

(13). The Global Assessment of Functioning Scale score is a global rating of overall psychological, social, and occupational functioning. The Mini-Mental State is a well-known and widely used brief mental status test of cognitive function. The test consists of 13 questions that assess orientation to place and time, learning and memory, construction ability, attention, and calculation skills. The possible range of scores is 0–30, for which scores less than 8 represent severe impairment and scores greater than 26 represent no impairment. The Mattis Dementia Rating Scale is a more extensive screening instrument designed to assess cognitive functioning in patients with dementia. The scale consists of 36 items that assess function in five cognitive domains. 1) Attention, measured by having the subject repeat digit strings, follow one- and two-step commands, and count target letters embedded in a random array of letters. 2) Conceptualization, measured by requiring the subject to generate abstract concepts common to a series of items (two if presented verbally, three if presented visually). 3) Construction, a domain assessed with items that require the subject to engage in design copying and name writing. 4) Initiation/perseveration, assessed with items that ask the subject to name supermarket items, repeat series of rhymes, perform double-alternating hand movements, and copy rows of alternating symbols, and 5) memory, measured with items that assess orientation, delayed recall of two sentences, and recognition memory for word-pair and design-pair series. The Mattis Dementia Rating Scale was selected as the primary measure because it yields a total score as well as individual domain scores that represent functioning in relatively discrete cognitive areas. The domain titles are self-explanatory except for initiation/perseveration, which is generally considered to be reflective of executive ability.

Procedures

All subjects received a comprehensive evaluation performed by a multidisciplinary geropsychiatric team

(14). This diagnostic evaluation included a psychiatric history and mental status examination, a social and medical history, a physical examination, structural magnetic resonance imaging scans (for depressed subjects) and laboratory tests, including EEG recordings. The assessment also included the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders, Patient Edition

(15). On the basis of all information available, consensus axis I and axis II diagnoses were established according to DSM-IV criteria by faculty psychiatrists and research staff. Subjects underwent cognitive evaluation with a large test battery before being randomly assigned to one of the treatments (nortriptyline or paroxetine). Subjects underwent a more limited reassessment following remission of their depression. Remission was defined as a score of ≤10 on the Hamilton depression scale for 3 consecutive weeks.

Results

Forty-five subjects achieved successful remission of their depressive symptoms within the treatment protocol, whereas 17 subjects failed to do so. Most of the subjects who achieved remission (N=41) did so after 12–14 weeks of treatment with the agent to which they were originally assigned. The other four patients were unable to tolerate the associated side effects of the treatment to which they were originally assigned and so were openly switched to the other medication after 2–3 weeks; each then responded. These subjects were reassessed following 12 weeks of treatment with the new drug. There were no significant differences between responders and nonresponders on a number of characteristics, including age (t=1.5, df=60, p<0.15), education (t=–1.6, df=60, p<0.13), and baseline scores on the Global Assessment of Functioning Scale (t=–0.3, df=60, p<0.80), Mini-Mental State (t=–0.9, df=60, p<0.38), and Mattis Dementia Rating Scale (t=–0.8, df=60, p<0.41). The Hamilton depression scale scores of the nonresponders (mean=24.5, SD=4.9) were slightly but nonsignificantly higher than those of the responders (mean=22.2, SD=3.8) (t=–1.9, df=60, p<0.06), which likely contributed to these subjects failing to meet our conservative criterion for remission (Hamilton depression scale score ≤10 for 3 consecutive weeks). Most important, as a group, the cognitive functioning of nonresponders was similar to that of study subjects who responded to therapy. Therefore, these analyses focus on the 45 patients who responded to pharmacotherapy.

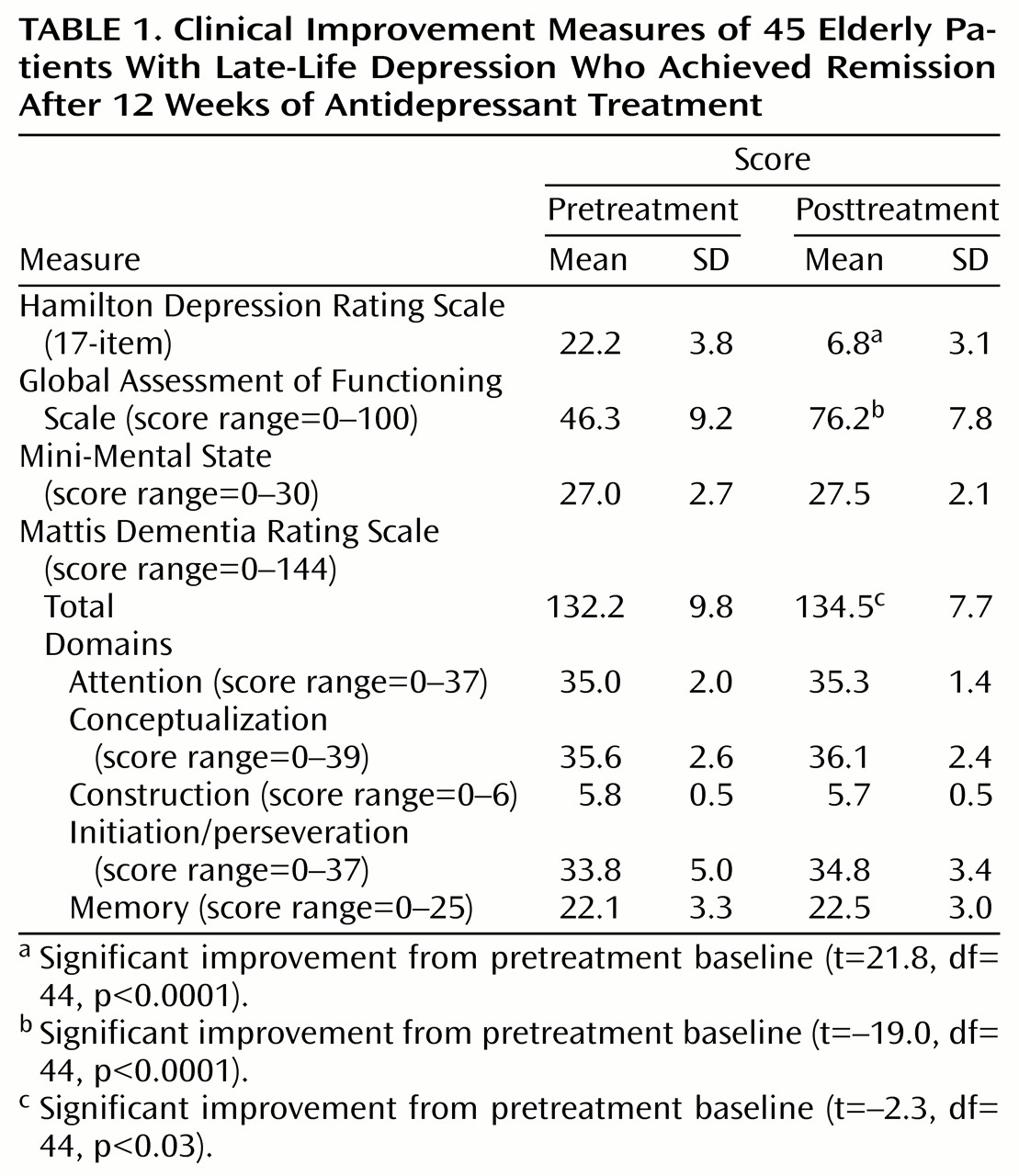

The 45 patients who responded to antidepressant treatment were a mean age of 72.9 years (SD=7.2) and had 11.5 (SD=2.8) years of education. Thirty-six (80.0%) of the depressed subjects were female, and 37 (82.2%) were Caucasian. Pre- and posttreatment clinical data for these subjects are presented in

Table 1. Large decreases in scores on the Hamilton depression scale and large increases in scores on the Global Assessment of Functioning Scale indicated successful treatment of depressive episodes in these subjects. Pre- and posttreatment cognitive functioning was compared. Across all subjects, Mini-Mental State scores did not change (t=–1.6, df=44, p<0.10), but a modest improvement was seen in total score on the Mattis Dementia Rating Scale that was statistically significant (

Table 1). Comparisons of individual Mattis Dementia Rating Scale domains suggested that the change in total score was due to small changes across most domains and not to improvements in any one domain in particular.

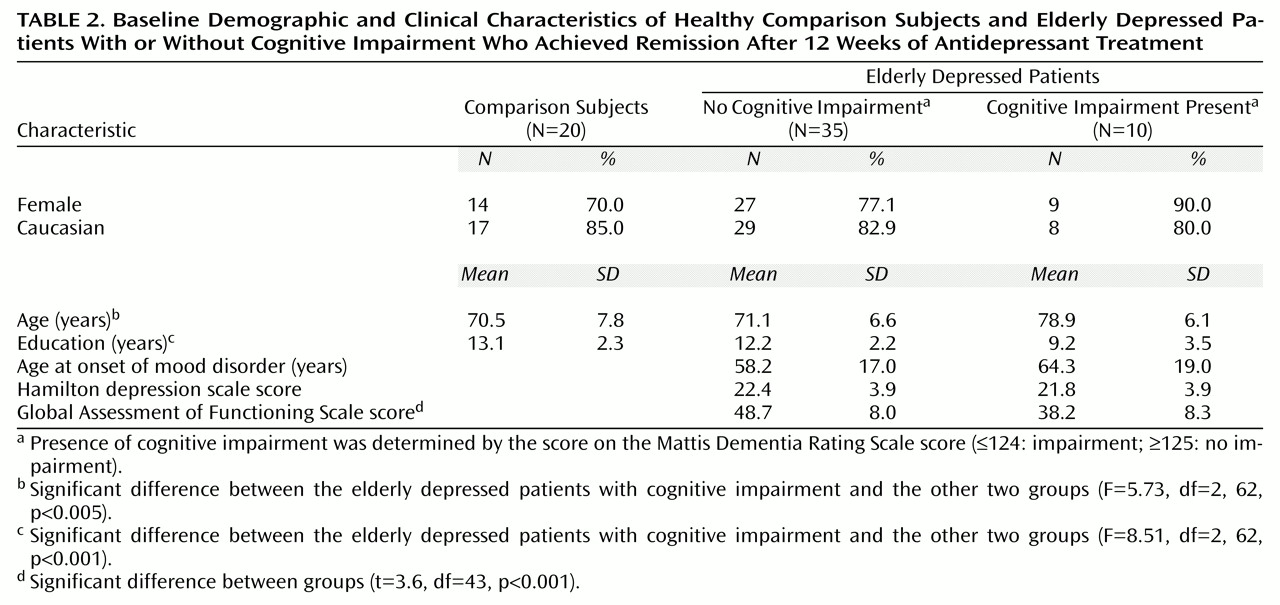

Using a pretreatment cutoff score of 124 on the Mattis Dementia Rating Scale, which is two standard deviations below the normative mean

(12,

15), we then divided the 45 elderly depressed subjects into two groups: those with no cognitive impairment (N=35) and those in whom cognitive impairment was present (N=10). Baseline characteristics of the elderly depressed patients as a function of their Mattis Dementia Rating Scale score and of a group of elderly comparison subjects are shown in

Table 2. There were significant differences between the groups in terms of age and years of education. Post hoc tests (Tukey’s honestly significant difference) revealed that the depressed patients with cognitive impairment were older than both the depressed patients without cognitive impairment (p<0.007) and the elderly comparison subjects (p<0.007), who were not different from one another (p<0.96). The depressed patients with cognitive impairment were also less educated than both the depressed patients without cognitive impairment (p<0.004) and the elderly comparison subjects (p<0.001), who were not different from one another (p<0.41). The groups did not differ in terms of either gender (χ

2=1.50, df=2, p<0.47) or racial distribution (χ

2=2.17, df=4, p<0.71). There also were no differences between the two depressed groups in terms of the age at which they experienced their first lifetime episode of depression (t=–9.7, df=43, p<0.45) or their baseline Hamilton depression scale score (t=0.4, df=43, p<0.69). However, there was a significant difference in overall functioning as measured by the baseline Global Assessment of Functioning Scale scores, which probably reflected the difference in the variable of interest, cognitive functioning.

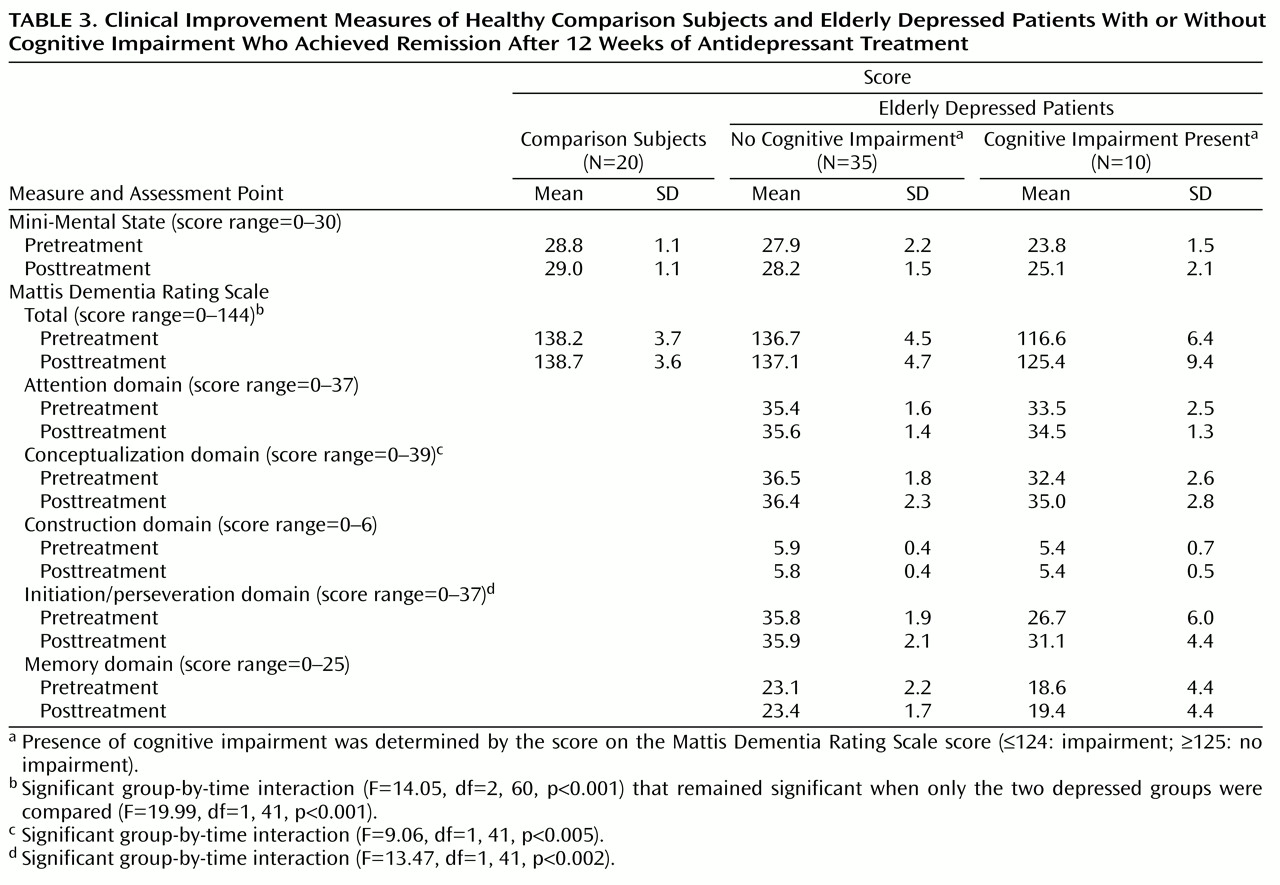

Table 3 shows pre- and posttreatment scores on the Mini-Mental State and Mattis Dementia Rating Scale for the elderly depressed patients with and without cognitive impairment along with the scores of the elderly comparison subjects tested at the same time points. To test for differences between groups as a function of treatment, two-factor (group, time) repeated measures analyses of covariance (covarying for age and education) that compared pre- and posttreatment scores were conducted. Analysis of Mini-Mental State scores yielded a main effect of group (F=19.15, df=2, 60, p<0.001) but not time (F=0.35, df=1, 60, p<0.56); the group-by-time interaction was also not significant (F=0.48, df=2, 60, p=0.63). Analysis of Mattis Dementia Rating Scale scores yielded a main effect of group (F=40.03, df=2, 60, p<0.001) and a significant group-by-time interaction (F=14.05, df=2, 60, p<0.001), revealing different patterns of change in the three groups; there was no main effect of time (F=1.96, df=1, 60, p<0.17). Planned contrasts found no significant differences in overall Mattis Dementia Rating Scale scores across the two testing points between the elderly comparison subjects and the elderly depressed patients without cognitive impairment (contrast estimate=–1.37, p<0.24). The scores of the elderly depressed patients with cognitive impairment improved significantly as a function of treatment (contrast estimate=–15.31, p<0.001).

Given that there were no differences in cognitive functioning between the elderly comparison subjects and the elderly depressed patients without cognitive impairment, the remaining analyses focused on comparisons between the latter group and the elderly depressed patients with cognitive impairment. Pre- and posttreatment scores for individual Mattis Dementia Rating Scale domains, covarying for age and education, differed between the two groups (

Table 3). The interaction of group-by-treatment was significant for both the conceptualization and the initiation/perseveration domains. The interaction was not significant for the other Mattis Dementia Rating Scale domain scores. These results suggest that the significant group-by-time interaction for Mattis Dementia Rating Scale total scores was largely due to improvement seen in the conceptualization and initiation/perseveration domains.

Discussion

This study investigated the changes in cognitive functioning following successful treatment of geriatric depression. The measured change in the Mattis Dementia Rating Scale total score for the patients was due to small changes across most domains and not to improvements in any one domain in particular. Among late-life depression subjects who had no cognitive impairment at study entry, there was no change in cognitive function as a result of treatment, whereas successful depression treatment led to significantly improved cognitive functioning among elderly depressed patients with baseline cognitive impairment. This was due to gains on measures of initiation/perseveration and conceptualization, which are both related to executive functioning.

These data suggest that depressed elders with cognitive impairment may experience improvement in specific cognitive domains but may not necessarily reach normal levels of performance. Furthermore, despite improved scores, the posttreatment performance of the elderly depressed patients with cognitive impairment remained well below that of the elderly depressed patients without cognitive impairment on both the initiation/perseveration and memory domains of the Mattis Dementia Rating Scale.

These findings add to the growing body of evidence that late-life depression is frequently associated with cognitive dysfunction and that the underlying defect is in the subcortical/frontal lobe neural circuitry. Impairment in executive functioning is a consistent finding in neuropsychological studies of late-life depression and can occur as a result of either structural damage to the prefrontal cortex or afferent subcortical structures (particularly striatal components of the basal ganglia). Late-life depression is also associated with central nervous system (CNS) structural changes; neuroimaging studies have found that late-life depression is associated with decreased parenchymal tissue density as well as central and cortical atrophy

(16–

18), basal ganglia lesions

(18), decreased volume or density of the caudate and lenticular nuclei

(19), and diffuse high signal hyperintensities in subcortical white matter (e.g., references

20–

24). While the relationship between structural CNS integrity and cognition in late-life depression has not been well studied, in general, structural abnormalities are associated with cognitive impairment

(23,

25,

26). White matter hyperintensities are associated with psychomotor slowing

(21) and executive function impairment, particularly in late-life depression subjects with late-onset depression

(4,

27).

Taken together, these neuroimaging findings suggest a relationship between late-onset depression, white matter hyperintensities (especially in the caudate and frontal lobe deep white matter), and executive dysfunction. Therefore, structural changes in the brain may play an important role in the etiology and pathophysiology of many cases of late-onset depression. Basal ganglia changes are associated with affective disorder

(28) as well as executive impairment through subcortical-frontal system dysfunction (e.g., reference

29). Therefore, changes in the basal ganglia may explain both the affective and executive dysfunction components of many cases of late-life depression.

What accounted for the selective increase of cognitive functioning in elderly depressed patients with, but not those without, cognitive impairment? And among the elderly depressed patients with cognitive impairment, what accounted for the selective increase in executive functioning, particularly relative to their impaired memory? We speculate that many of these impaired patients were experiencing underlying CNS changes that lowered their cognitive reserve, making them vulnerable to the toxic effect of depression on cognition. In contrast, the elderly depressed patients without cognitive impairment likely had a more structurally intact CNS and thus more cognitive reserve to withstand the stress of depressed mood. Of note, the memory domain scores in the elderly depressed patients with cognitive impairment remained in the impaired range after successful depression treatment. These stable memory deficits may, in many of these subjects, be an indicator of the underlying structural changes that are associated with early Alzheimer’s disease.

There were some limitations of this study. First, patients could be treated with one of two different antidepressants; either or both drugs could exert independent deleterious effects on cognition (e.g., related to anticholinergic properties). While this might account for the lack of improvement in memory, it does not explain the improvement in executive functioning, which, if anything, may represent an underestimate of the actual improvement related to change in affective state. Second, our hypothesis that cognitive deficits would improve in subjects with cognitive impairment at study entry could be explained on the basis of regression to the mean, a factor inherent in interpreting test-retest results in clinical populations. However, these data suggest that late-life depression subjects with cognitive impairment exhibited

differential improvement on measures of executive functioning. If the improvement was largely due to regression to the mean, other domains (especially memory, which was quite poor at baseline), should have been similarly affected. Furthermore, the scores of the elderly depressed patients without cognitive impairment should have declined, which did not occur. Last is the related issue of the presence of test ceiling effects. Although the baseline Mattis Dementia Rating Scale scores attained by the elderly depressed patients without cognitive impairment were near the normative mean of 137

(12,

15) (i.e., 7 points below the maximum of 144), it is possible that they were at a “functional ceiling” (very few normal individuals score above the mean of 137). Thus, a low ceiling on the Mattis Dementia Rating Scale may have obscured treatment-related cognitive improvement in the “intact” group. More sensitive measures of cognitive function may have uncovered a more general improvement in brain functioning. Despite these factors, one of the most important findings from this study was the selective improvement in executive functions, especially relative to memory. A battery of more sensitive cognitive measures would be able to more fully address this improvement in executive ability and more fully define its relation to improving mood.