Substantial recent advances in molecular genetics have greatly increased the capacity to localize disease genes on the human genome. These methods are now being applied to complex disorders, including schizophrenia

(1–

4). One of the major difficulties in the application of these approaches is the likely etiologic heterogeneity of the schizophrenic syndrome. Such heterogeneity markedly reduces the power of gene-localization methods, such as linkage analysis (5–8). Therefore, to aid in these methods, it would be highly desirable to dissect the syndrome, at the level of the phenotype, into valid subsyndromes or diseases.

The deficit syndrome shows promise as a valid subtype within the syndrome of schizophrenia. Early in this century, Kraepelin

(9) described an amotivational syndrome within the broader syndrome of dementia praecox. Since then, there have been many twists and turns in the road toward understanding negative features of psychopathology in schizophrenia. The deficit syndrome has been proposed as a distinct subtype of schizophrenia characterized by primary and enduring negative features of psychopathology

(10,

11). Data supporting the validity of this concept have been provided by studies of etiological risk factors

(12–

14), course of illness

(11,

15–

21), neurological signs

(22), functional and structural brain imaging

(23–

25), neurocognitive measures

(26–

31), and treatment

(32,

33).

Despite the wide variety of validating studies, there has been little examination of familial or genetic aspects of the deficit syndrome. We know of only two published reports of this type, which showed that relatives of patients with the deficit syndrome, in comparison with relatives of nondeficit patients, have a higher prevalence of schizophrenia

(12) and a higher prevalence of social isolation

(34). We know of no data indicating whether the prevalence of the deficit syndrome is higher in relatives of deficit patients than in relatives of nondeficit patients.

In addition to the direct evidence, indirect evidence suggests that the deficit syndrome has important familial or genetic underpinnings. The deficit syndrome is associated significantly with smooth-pursuit eye tracking disorder

(28,

31), which has been proposed as a more valid phenotype for genetic studies in schizophrenia

(35–

37).

In the current study we addressed the question of a familial factor underlying the deficit syndrome by examining affected sibling pairs ascertained in the Irish Study of High-Density Schizophrenia Families

(38). The purpose of the current study was to test the hypothesis that pairs of schizophrenic relatives resemble one another for the deficit versus nondeficit subtype at greater than chance expectations.

Method

Sample

As detailed elsewhere

(38), the Irish Study of High-Density Schizophrenia Families is a collaboration of the Medical College of Virginia, the Health Research Board, Dublin, and the Queen’s University, Belfast. Families containing a high density of schizophrenia and related disorders were ascertained through 39 separate public psychiatric hospitals in Ireland and Northern Ireland.

Interviews were conducted by Irish psychiatrists and social scientists with a background in mental health or survey work after consent was obtained by using procedures approved by the ethical review panels at the Health Research Board and the Queen’s University. Whenever possible, individuals suspected of having psychosis were interviewed by a psychiatrist. All interviewers underwent extensive initial and ongoing training in the use of diagnostic instruments by one of us (K.S.K.).

Our assessment instruments consisted of modified sections of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID)

(39) for selected axis I disorders and the Structured Interview for Schizotypy

(40) for schizophrenia spectrum personality disorders. For 98.6% of the subjects diagnosed with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder, we obtained psychiatric inpatient and/or outpatient records. A detailed abstract of these records was dictated, and a specially developed case record rating scale was completed. No attempt was made, during the assessments of individual relatives in the Irish Study of High-Density Schizophrenia Families, to keep the interviewer blind to information about the psychiatric status of other relatives. All relevant diagnostic information for each individual relative was reviewed independently by two us (K.S.K. and D.W.). The interviewers performing these assessments were blind to pedigree assignment and knowledge of the psychopathologic status of other relatives. Diagnostic disagreements were resolved by consensus.

In this study we defined “affected” status as one of the following diagnoses: 1) schizophrenia, based on DSM-III-R criteria, with diagnostic certainty classified as definite, probable, or possible; 2) schizoaffective disorder, based on DSM-III-R criteria, with poor outcome

(38) and a level of diagnostic certainty classified as definite or probable; and 3) simple schizophrenia, based on criteria outlined elsewhere

(41), with definite or probable diagnostic certainty.

Assessment of Deficit Syndrome

The information available on siblings (described in the preceding) was used to make a deficit/nondeficit categorization, according to previously published criteria

(11). The rating for each proband was made by one of two raters (D.E.R. or B.K.) blind to information about the sibling(s). The two raters conducted an interrater reliability exercise with a subset of probands from the Roscommon Family Study

(42), which used methods for clinical assessment that were similar to those used in the Irish Study of High-Density Schizophrenia Families. There was agreement on 11 of 12 subjects (92% agreement; kappa=0.82, SE=0.17).

Statistical Methods

Resemblance in sibling pairs was examined by hierarchical log-linear regression. Since this analysis contained nonindependent sibling pairs from sibships containing three or more affected individuals, we repeated these analyses, picking one or more pairs at random from sibships with three or more affected members. Covariates in the model included age, sex, and duration of illness. The analysis began with a saturated model and proceeded with backward elimination of nonsignificant terms. The goodness of fit of the resulting model was evaluated with the likelihood ratio statistic, G2.

Results

Sample

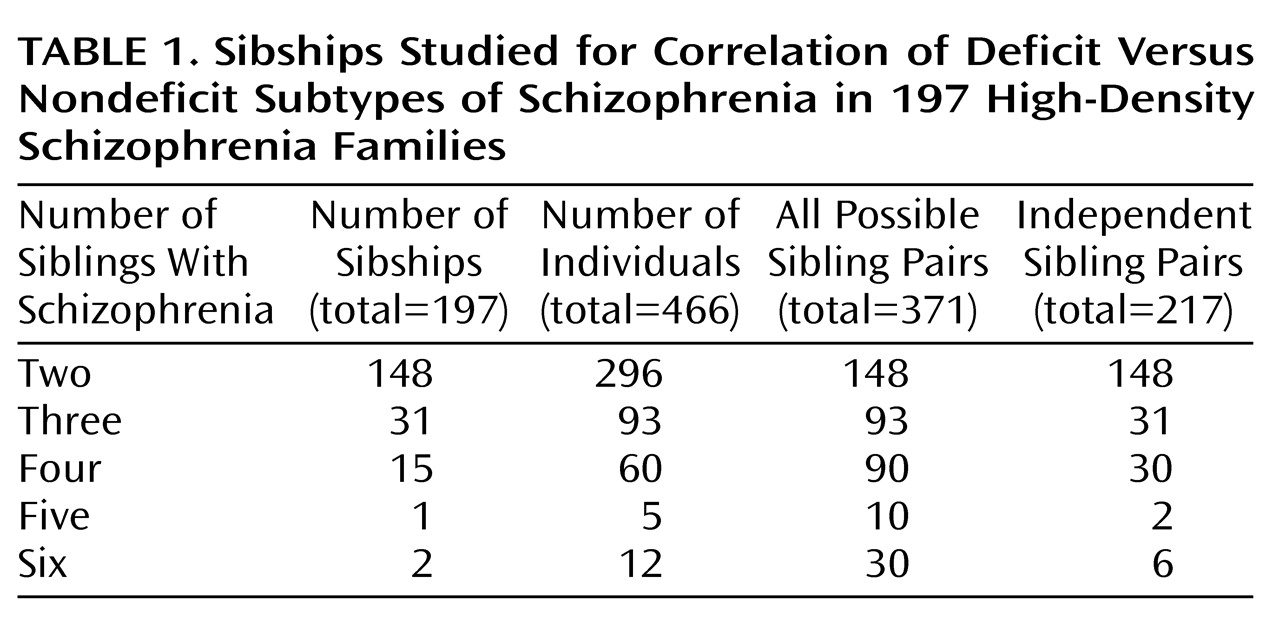

The sample contained 481 subjects who were members of full sibling pairs concordant for schizophrenia (definite, probable, or possible), schizoaffective disorder with poor outcome (definite or probable), or simple schizophrenia (definite or probable). We were able to make determinations of deficit versus nondeficit subtype for 466 subjects (96.9%), leaving 15 subjects (3.1%) who could not be assessed because sufficient information was lacking. Of the 481 original subjects, 309 (64.2%) were male, and the mean ages at onset and evaluation were 24.1 years (SD=7.8) and 45.2 years (SD=13.3), respectively. As shown in

Table 1, the 466 subjects with deficit/nondeficit subtypes came from 148 sibships with two affected members, 31 with three affected members, 15 with four affected members, one with five affected members, and two with six affected members. Sixty-five of the 466 subjects (13.9%) were judged to have the deficit subtype. The 466 subjects included 371 full sibling pairs. Age at onset, sex, and duration of illness were available for 347 full sibling pairs, which were used in the regression analyses.

Sibling Resemblance for Deficit Versus Nondeficit Subtype

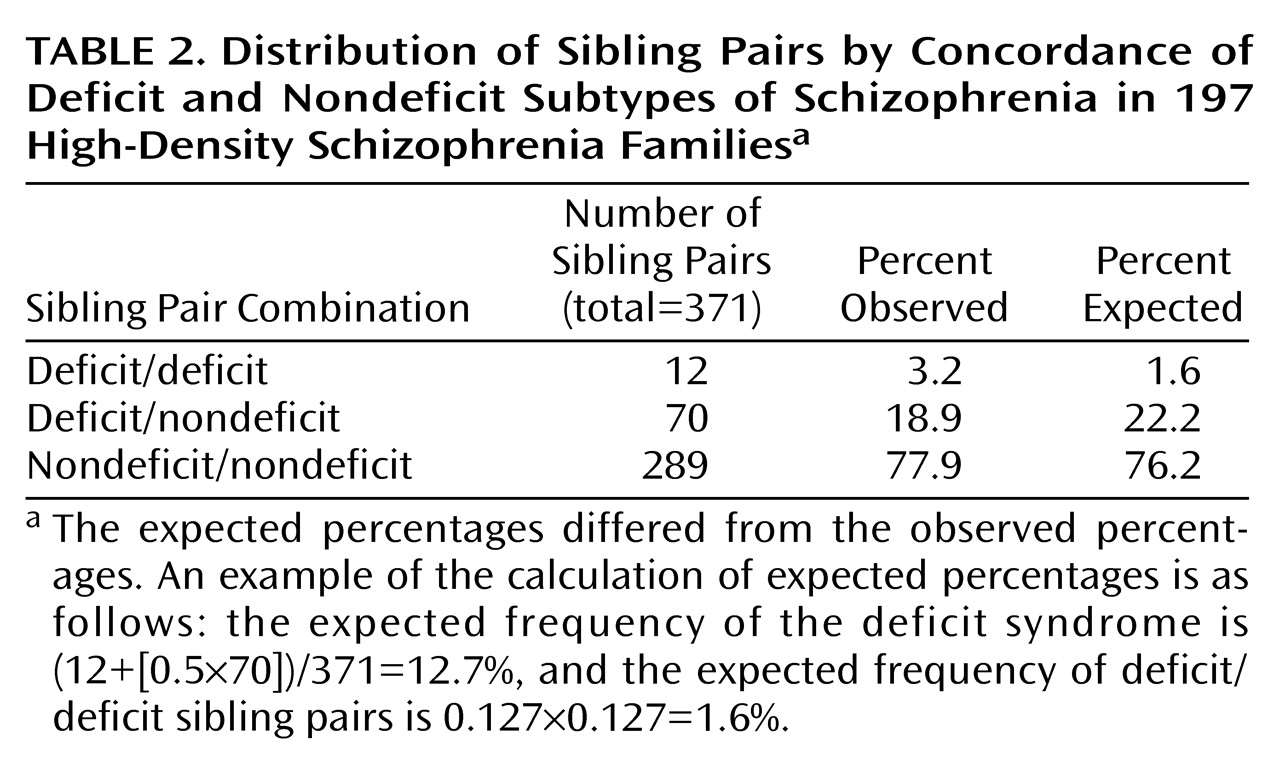

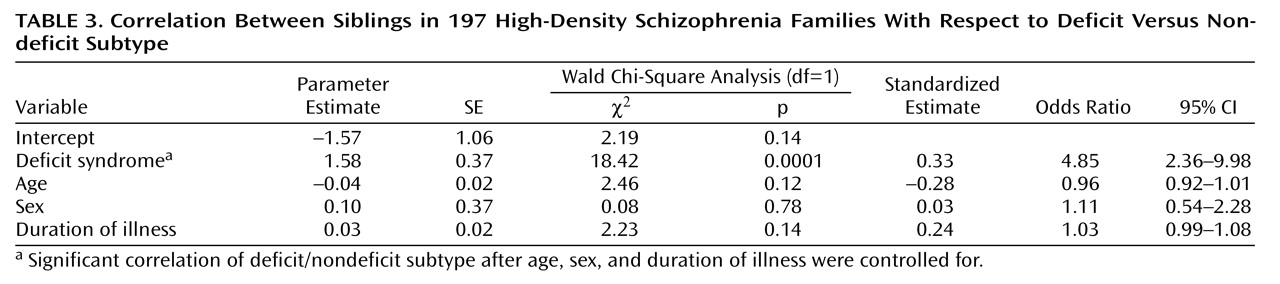

When we controlled for age, sex, and duration of illness, the siblings resembled each other significantly with respect to deficit versus nondeficit status (

Table 2 and

Table 3). We repeated this analysis after removing nonindependent sibling pairs. The results were similar, with a significant correspondence between sibling pairs with respect to deficit versus nondeficit status (Wald χ

2=5.34, df=1, p=0.02; odds ratio=3.35, 95% confidence interval=1.20–9.34).

Discussion

The main finding was a significant correlation between siblings with respect to deficit versus nondeficit subtype. To our knowledge, this is the first report of familial resemblance for the deficit syndrome in patients with schizophrenia and closely related disorders.

Previous Studies of Familial Aspects of Deficit Syndrome

The deficit syndrome has been proposed as a distinct subgroup within the syndrome of schizophrenia

(10,

11). Although the validity of this approach is supported by an impressive amount of research, few data on familial and genetic aspects of the deficit syndrome are available. Given the recent focus on genetics and determination of valid phenotypes, such studies are of interest. A previous study

(12) showed that relatives of deficit patients, in comparison with relatives of nondeficit patients, had a significantly higher prevalence of schizophrenia and a significantly lower prevalence of suicide. In another study

(34), relatives of deficit probands, in comparison with relatives of nondeficit probands, had significantly greater social isolation despite significantly less severe dysphoria and psychotic-like symptoms. In summary, the results of those studies are generally consistent with the results of the current one, with all studies supporting a familial aspect to the deficit syndrome.

Other Studies of Familial Aspects of Negative Features in Schizophrenia

To our knowledge, there have been no other published reports on familial characteristics of the deficit syndrome. However, several studies have examined familial aspects of more broadly defined negative features of psychopathology. (Unless otherwise stated, the term “negative features” will be used in the following to refer to more broadly defined negative features of psychopathology.) Several of these studies have provided evidence for a familial aspect of negative features. Although the concepts of negative features and the deficit syndrome differ in important ways, they also overlap to a moderate extent. Therefore, it seems useful to review the literature regarding the familial nature of negative features in schizophrenia.

Previous Sibling Studies

Irish Study of High-Density Schizophrenia Families

Several analyses of negative features in sibling pairs, including monozygotic twins, have been conducted. In a previous set of analyses from the Irish Study of High-Density Schizophrenia Families

(43), negative features also were found to be correlated significantly between siblings. The current study differs from the previous one in that patients were divided into those with and without the deficit syndrome, which is defined on the basis of primary and enduring negative features. It has been argued theoretically that this is a distinction of fundamental importance

(10,

11). Also, this concept has been supported empirically by several studies that examined the deficit syndrome and negative features in the

same sample. In many cases, the deficit syndrome was found to be associated significantly with the validator of interest, but negative features were not

(14–

16,

19,

21). Contrary to this pattern of results, but also in support of the distinction between the two concepts, improvement in negative features after treatment with atypical antipsychotic medication has been found to be associated with negative features but not with deficit features

(32). Thus, the previous finding of sibling resemblance for negative features in the Irish Study of High-Density Schizophrenia Families did not necessarily indicate that the same would hold true for the deficit syndrome.

Other sibling studies

Other studies of sibling pairs also have provided support for a familial aspect underlying negative features. Negative features have been found to be concordant in sibling pairs affected with schizophrenia

(44,

45). Concordance rates for negative and positive features were higher for monozygotic twins in cases in which the proband had a greater number of negative features

(46). Monozygotic twins concordant for schizophrenia had more negative features than did those who were discordant

(47). However, DeLisi and colleagues

(48) examined 53 sibling pairs concordant for schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder and found no significant resemblance for negative features.

Previous Family Studies

More generally, greater familial loading for schizophrenia has been found to predict persistence of negative features in the proband

(49). Also, a psychopathological dimension characterized by flat affect and insidious onset has been found to predict higher risk of psychosis in relatives

(50). On the other hand, negative features did not predict family characteristics in the Roscommon family study

(51).

Overall, most of the studies in this area support a familial aspect of negative features in schizophrenia. This conclusion is generally consistent with the main finding of the current study.

Is the Familial Distinction Between Deficit and Nondeficit Subtypes Related to a Genetic Factor?

The main finding of this study supports a familial aspect of the deficit syndrome, but it leaves open the question of whether the familial resemblance is due to environmental or genetic factors. We addressed the latter issue in a preliminary way by examining the relationship between deficit status and family lod scores for several chromosomal regions previously implicated in schizophrenia, including 5q22-31

(52), 6p24-22

(1), 8p22-21

(53), and 10p15-p11

(54). Using log-linear regression analyses, we found no significant association between a higher prevalence of the deficit syndrome and the family lod score for any of the chromosomal regions (data available on request). There was a significant association between the nondeficit subtype and a higher lod score for 5q (df=1, p=0.04). However, this association was not significant after we corrected for multiple statistical tests, and even if it were, it would be difficult to interpret. Overall, the most straightforward interpretation of these results is that the deficit syndrome is not associated with genetic defects in these regions. However, it is also possible that our chart review methods were not sufficiently sensitive to detect an association that actually existed. It would be better to test such hypotheses by using assessments of deficit syndrome based on face-to-face interviews of patients and informants. In either case, it also remains possible that the deficit syndrome is associated with defects of other genetic regions.

Conclusions

The finding of sibling resemblance in the deficit versus nondeficit subtype of schizophrenia adds support to the utility of the deficit subtype as a phenotype within the syndrome of schizophrenia. It is not known how this finding of familial resemblance is related to genetic or environmental factors. Future studies should use face-to-face interviews for assessing the deficit syndrome and molecular genetic strategies to explore potential genetic relationships.