Medication

(1–

3) and cognitive behavior therapy

(4–

6) are efficacious treatments for panic disorder. A decade ago, these treatments were endorsed at an NIH Consensus Development Conference

(7), at which the lack of information about other forms of psychotherapy was also specifically noted. Recent surveys suggest that many patients with panic disorder still receive forms of psychotherapy other than the recommended cognitive behavior therapy

(8), and the efficacy of such treatment remains untested. This deficiency needs to be addressed.

We previously reported results of a “nonprescriptive” psychotherapy

(9). In a study that compared 3 months of weekly therapy to an equal period of cognitive behavior therapy in panic disorder patients with or without agoraphobic avoidance, we found no difference between the two treatments. However, this study had several limitations. Patients with moderate to severe agoraphobia were included, which differentiated this study from other cognitive behavior therapy studies. In addition, panic attack frequency—known to be an unstable metric—was used as the main outcome measure, and there was no control treatment group. To surmount these problems, we conducted the present replication and extension study, which used a similar form of psychotherapy, called emotion-focused psychotherapy, that involved empathic listening and supportive strategies to help patients identify and manage painful emotions and troubling life situations. We compared emotion-focused psychotherapy to treatment with either cognitive behavior therapy or imipramine in a group of panic disorder patients with no more than mild agoraphobia that had been treated at our site as part of a four-site collaborative study

(10). We further compared results obtained with emotion-focused psychotherapy to those seen in patients at all four sites who received placebo.

Method

We have previously described emotion-focused psychotherapy

(11). In brief, this treatment consists of a reflective listening approach, with systematic exploration of the circumstances and details of emotional reactions. The treatment is based on the premise that unrecognized emotions trigger panic attacks and contribute to the maintenance of the disorder. In particular, emotions are evoked by interpersonal problems associated with a sense of loss of control or the possibility of being abandoned or trapped. If the resulting fear, anger, guilt, or shame is disavowed or otherwise avoided, the result is a vague sense of unease, often misattributed to a physical condition. The emotion-focused therapist was alert to indications of unacknowledged negative feelings and sought, with varying success, to help the patient identify and process such emotions. Strategies and techniques for interventions were outlined in a detailed treatment manual. Although forms of psychotherapy other than cognitive behavior therapy used in the community have not been well specified, we believe that emotion-focused psychotherapy bears resemblance to such usual-care psychotherapy. Emotion-focused psychotherapy was not a psychoanalytic psychotherapy in that the therapist did not utilize transference and did not formulate or provide psychodynamic interpretations.

We compared treatment with emotion-focused psychotherapy to treatment with cognitive behavior therapy or imipramine, which had been provided under the auspices of a four-site comparative treatment study of panic disorder

(10). Treatment in the current study consisted of 3 months of weekly sessions (acute phase) followed by six monthly maintenance visits (maintenance phase). Sessions of cognitive behavior therapy and emotion-focused psychotherapy lasted approximately 60 minutes; imipramine sessions lasted less than 30 minutes. As in the four-site study, all subjects treated with psychotherapy were offered continued maintenance treatment. Patients given imipramine continued only if they had responded. Assessments by blinded raters, certified and monitored for reliability, were conducted at four time points: at baseline, after the acute and maintenance phases, and at a follow-up visit after 6 months of no treatment.

Subjects

Study participants were referred by clinicians, self-referred, or responded to media advertising. Those whose screening examination results suggested the presence of panic disorder were recruited for participation and signed written informed consent. In order to participate in the collaborative study, subjects were required to discontinue any psychotropic medication and ongoing psychotherapy. The diagnosis of panic disorder with no more than mild agoraphobia was confirmed by using the Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule—Revised

(12). Mild agoraphobia was defined as a score ≤18 on avoidance ratings of agoraphobic situations. In addition, inclusion criteria required at least one full or limited panic attack per week in the 2 weeks before the first treatment visit. Exclusion criteria included presence of any psychotic disorder, bipolar disorder, suicidality, significant substance abuse, or significant medical illness as well as prior nonresponse to cognitive behavior therapy or imipramine for panic disorder and a concurrent disability claim.

Recruitment for this emotion-focused psychotherapy study began during the third year of the four-site study; subjects were randomly assigned to receive emotion-focused psychotherapy in a 1:6 ratio. When the four-site study ended, seven patients had been assigned to receive emotion-focused psychotherapy. In order to complete the emotion-focused psychotherapy group, we used two strategies. First, 13 subjects who met all entry criteria for the collaborative study except willingness to discontinue medications or to agree to random assignment were treated with emotion-focused psychotherapy. Second, we continued recruitment following termination of the four-site study by randomly assigning patients to either emotion-focused psychotherapy (N=10) or cognitive behavior therapy (N=14). Baseline scores were not significantly different among patients recruited in the three ways. We report here results for all 30 subjects treated with emotion-focused psychotherapy, along with 36 subjects treated with cognitive behavior treatment (22 as part of the collaborative study), and 22 subjects who were treated at our site with imipramine during the collaborative study. Assessment procedures were identical for all subjects.

In addition to comparing emotion-focused psychotherapy to active treatment, comparison with a treatment control is of interest. However, only six patients were treated with pill placebo at our site in the four-site study. Consequently, we compared results obtained with emotion-focused psychotherapy to those seen in subjects treated with placebo at all four sites. Although no site differences had been detected

(10), we conducted the comparison between emotion-focused psychotherapy and pill placebo separately because of the inclusion of subjects from other sites.

Therapists

Cognitive behavior therapists were master’s- or doctoral-level clinicians who completed required training and certification under the supervision of David Barlow, Ph.D., and colleagues. Pharmacotherapists were psychiatrists who completed required certification under the supervision of Jack Gorman, M.D., and colleagues. Emotion-focused psychotherapists were doctoral-level clinicians with at least 3 years experience, trained to proficiency in emotion-focused psychotherapy by the first author. Therapists for all modalities received ongoing supervision of their cases during the entire study period.

Treatment Conditions

Cognitive behavior therapy targeted fear of bodily sensations. The treatment was administered according to procedures described in a treatment manual that contained specific instructions for each treatment session

(13). A patient handout contained information about anxiety and panic attacks and included a presentation of the fear of bodily sensations model used in this treatment.

Emotion-focused psychotherapy targeted emotional reactions and current life problems and used a reflective listening, supportive approach administered according to procedures described in a treatment manual available from the first author. In brief, the therapist helped the patient identify and manage difficult emotions, including panic and limited symptom episodes. A handout described the physiology of emotions and suggested that emotions can trigger panic attacks. Similar to usual psychotherapy, there were no homework assignments, and session content was not standardized. Instead, the discussion was individualized, based upon emotional reactions the therapist considered important, and included consideration of a current life problem that was causing emotional distress.

A manual was also used to guide administration of the double-blind medication treatment. There was a medical management component, specified in the manual, aimed at monitoring side effects, symptom status, and overall distress and impairment. The pharmacotherapist prescribed medication using a fixed-flexible dose regimen beginning with 10 mg/day, with a target dose of at least 200 mg/day. Specific interventions with cognitive behavior therapy or psychodynamic psychotherapy were prohibited.

All treatments included continuous daily panic monitoring. All included provision of information about panic disorder and a rationale for the treatment being provided. These components are common to proven efficacious treatments for panic disorder and have been recommended in published guidelines

(14).

Assessments

Study assessments were performed by independent evaluators who were certified as reliable and who were supervised throughout the study. Assessments were audiotaped, and random interviews were monitored for reliability. The primary continuous outcome measure was the average score on the Panic Disorder Severity Scale

(15), a clinician-rated scale that we developed for use in the four-site study. To provide a process measure of treatment effects, subjects completed a self-report measure, the Anxiety Sensitivity Index

(16), at each visit. Subjects also completed the Treatment Expectations Form

(17) at session 2 after they had been provided information about panic disorder and a rationale for the treatment they would receive. The form was completed privately and placed into a sealed envelope. Therapists did not see these ratings.

The primary, a priori categorical outcome measure was based on an anchored version of the Clinical Global Impression (CGI) scale

(18) that consisted of two 7-point scales that rated overall improvement and severity. Response was defined as a score of 2 (“much improved”) or better on the CGI improvement scale and a score of 3 (“mild”) or less on the CGI severity scale.

Statistical Analyses

The main comparisons were among the three active treatments—emotion-focused psychotherapy, cognitive behavior therapy, and imipramine—in terms of response (CGI improvement and severity scale scores) and scores on the Panic Disorder Severity Scale. Scores of patients in the three active treatment groups after the acute and maintenance phases and at the follow-up assessment were compared by using analyses of covariance while controlling for the baseline level of the measure.

In addition, the emotion-focused psychotherapy group was compared to the pill placebo group by using group t tests. We again compared response rates (CGI improvement and severity scale scores) and scores on the Panic Disorder Severity Scale after the acute and maintenance phases and at the follow-up assessment.

For the acute and maintenance phases, separate analyses were done for both the intent-to-treat and completer groups. For the intent-to-treat group, scores on the Panic Disorder Severity Scale at the end of the acute and maintenance phases were imputed from the previous time point (last observation carried forward) for patients who did not contribute data at all time points. This approach, used in our prior report

(10), allowed us to classify response status in all subjects. Also following our prior report, it was assumed that if a person did not complete the phase, their score would not change from the end of the previous phase. Response rates based upon the Panic Disorder Severity Scale and CGI scores were calculated for both the intent-to-treat and the completer groups after the acute and maintenance phases and compared with chi-square tests for contingency tables.

To test the anxiety sensitivity measure over time, we compared the three active treatments by using a mixed-effect random regression approach

(19) with SAS PROC MIXED. The random regression fits a separate intercept and slope over time for each subject. Overall fixed-effects measures of session, treatment, and the treatment-by-session interaction are tested with the F statistic.

Results

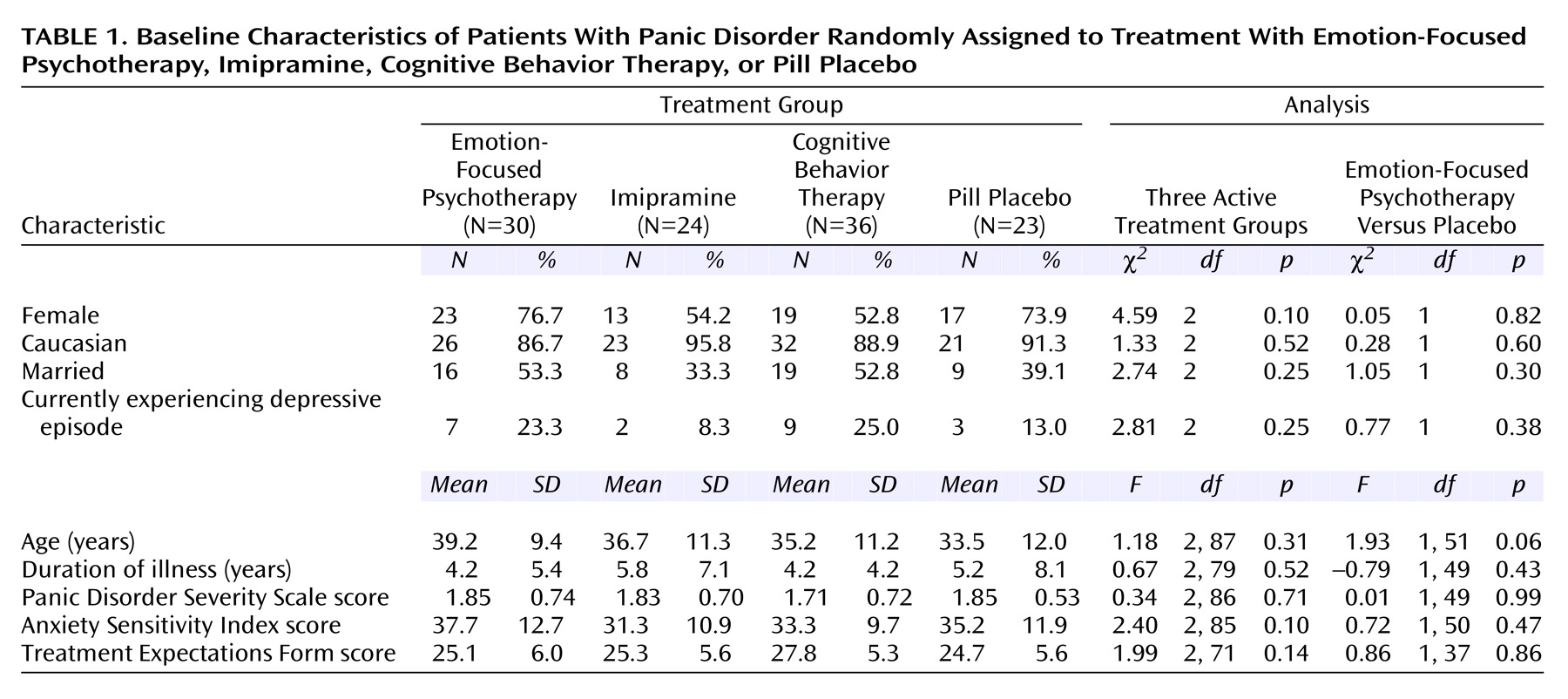

Table 1 shows baseline values for each treatment group. Panic disorder severity was moderate. There were no significant differences on demographic or clinical measures among the different treatment groups at baseline, nor was there a significant difference in treatment expectations across the four treatment groups.

Acute Phase

Comparison of active treatment groups

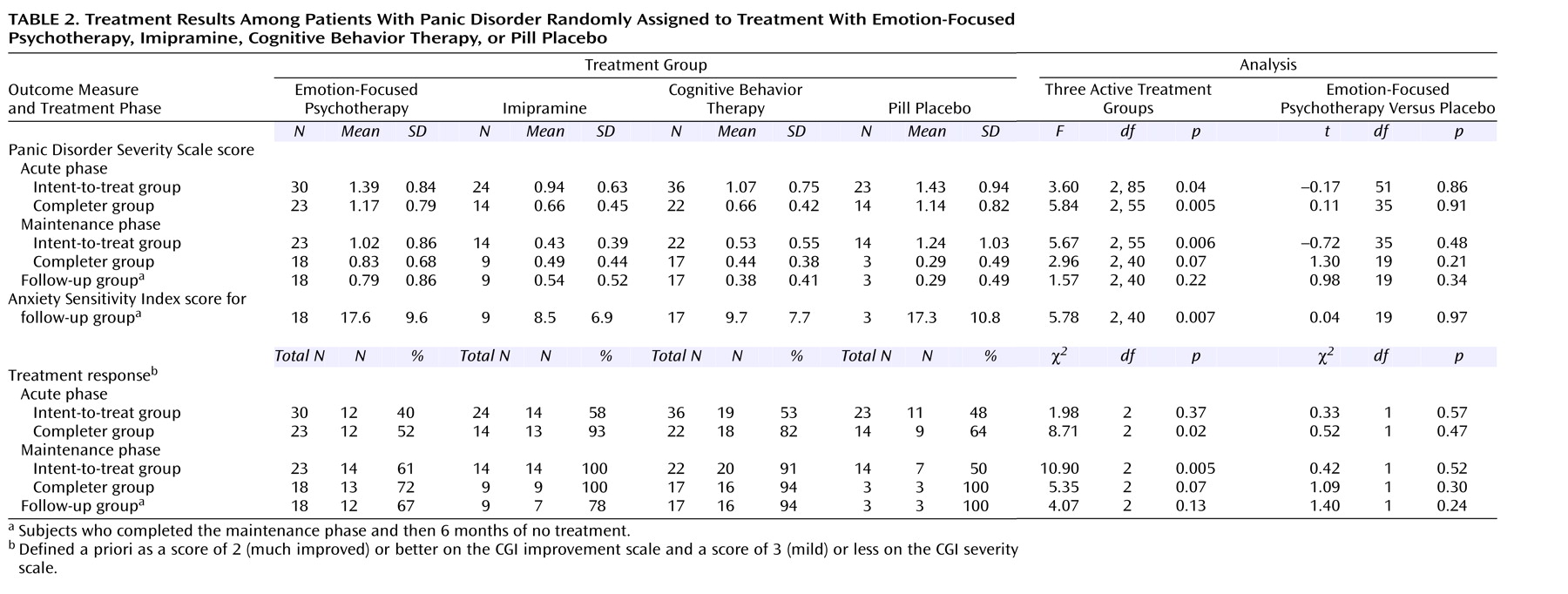

As seen in

Table 2, among patients who completed the acute phase, the rate of response for both cognitive behavior therapy (82%) and imipramine (93%) was superior to that of emotion-focused psychotherapy (52%). In addition, one subject receiving cognitive behavior treatment and one receiving imipramine dropped out of acute treatment as responders. Both cognitive behavior therapy and imipramine produced significantly greater reduction in scores on the Panic Disorder Severity Scale as well. Yet, among subjects in the intent-to-treat group, the response rate for emotion-focused psychotherapy (40%) was only slightly lower than that of imipramine (58%) or cognitive behavior therapy (53%), although Panic Disorder Severity Scale scores remained significantly higher in subjects who received emotion-focused psychotherapy.

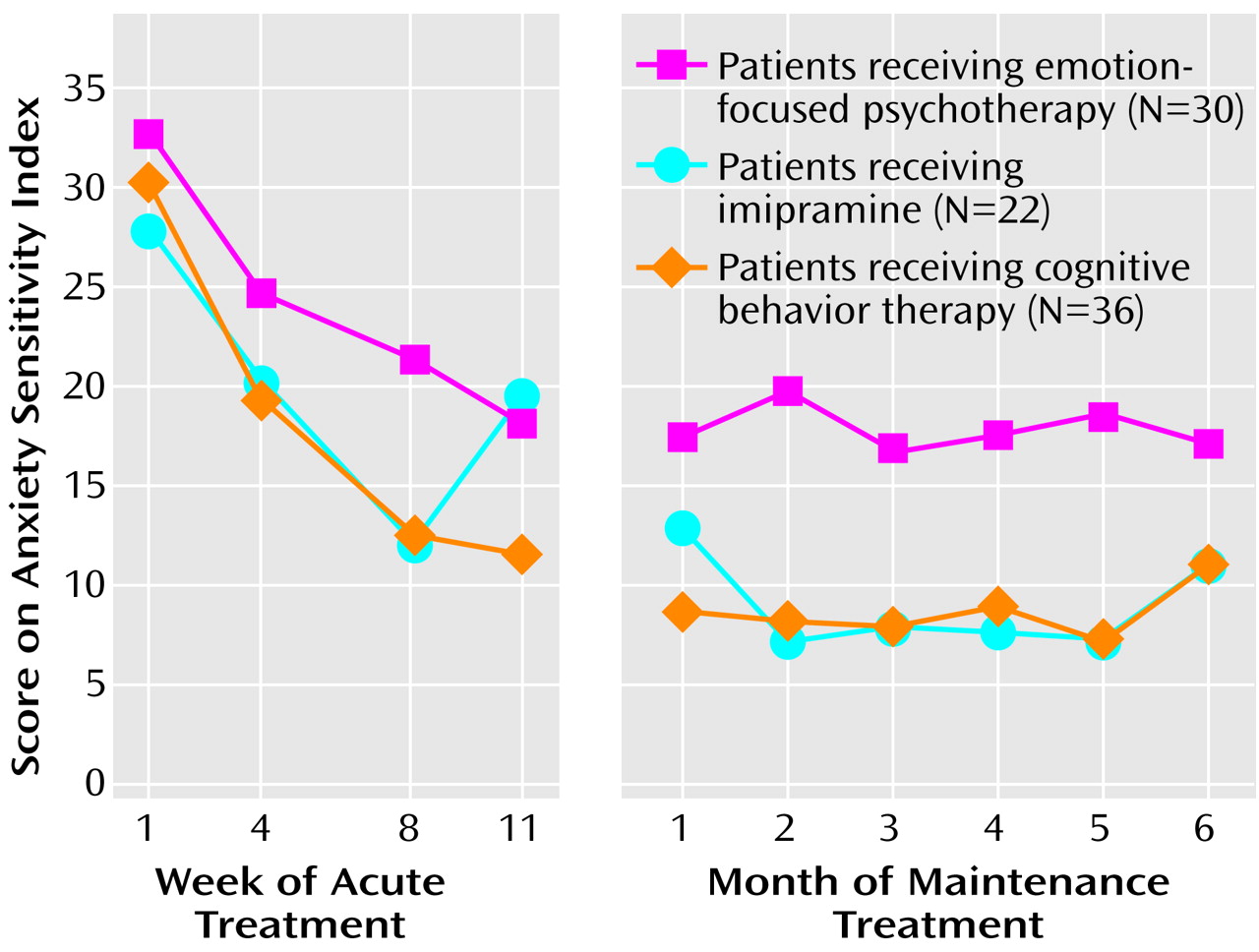

Figure 1 shows the results of the weekly assessments of anxiety sensitivity. Cognitive behavior treatment and imipramine produced lower scores on the Anxiety Sensitivity Index than emotion-focused psychotherapy. This effect was evident by week 4 of treatment. A random regression analysis on Anxiety Sensitivity Index score revealed that there was a statistically significant interaction between treatment and session (F=4.47, df=2, 461, p<0.02).

Emotion-focused psychotherapy versus placebo

Results for emotion-focused psychotherapy resembled those obtained with pill placebo (

Table 2). Of 23 subjects completing the acute phase of emotion-focused psychotherapy, 12 (52%) were judged to have responded, compared with nine (64%) of 14 given placebo. In the intent-to-treat group, 40% of subjects receiving emotion-focused psychotherapy and 48% of those given placebo responded, a nonsignificant difference. Similarly, there was no difference between emotion-focused psychotherapy and placebo on the Panic Disorder Severity Scale score for either completers or the intent-to-treat group.

Maintenance Phase

Comparison of active treatment groups

As shown in

Table 2, analysis of the intent-to-treat group revealed that significantly fewer of the patients receiving emotion-focused psychotherapy responded, and a significantly poorer outcome in terms of score on the Panic Disorder Severity Scale was seen for these patients as well. The pattern was similar for the completer group, although the results did not reach statistical significance. Also of note, three subjects treated with imipramine rated as having responded after the maintenance phase had actually dropped out of maintenance treatment as nonresponders but had regained their response in the ensuing weeks. This was also true for two subjects who received cognitive behavior therapy and one who received emotion-focused psychotherapy.

Anxiety sensitivity ratings during the maintenance phase are illustrated in

Figure 1. Random regression analysis showed a significant treatment effect (F=4.15, df=2, 110, p<0.02) and no treatment-by-time interaction (F=1.24, df=2, 110, p=0.29).

Emotion-focused psychotherapy versus placebo

Among those who completed the maintenance phase, 72% (N=13 of 18) of those receiving emotion-focused psychotherapy were judged to have responded, while all three of the patients receiving placebo who completed this phase responded. Analysis of the intent-to-treat group revealed that there was no significant difference between patients receiving emotion-focused psychotherapy and those receiving placebo in response rate or in mean score on the Panic Disorder Severity Scale (

Table 2>).

Treatment Completion

The acute phase was completed by 23 patients receiving emotion-focused psychotherapy (77%), 22 patients receiving cognitive behavior therapy (61%), 14 patients given placebo (61%), and 14 patients receiving imipramine (58%). The maintenance phase was completed by 78% (N=18 of 23) of the patients receiving emotion-focused psychotherapy, 77% (N=17 of 22) of the patients receiving cognitive behavior therapy, 64% (N=9 of 14) of the patients receiving imipramine, and 21% (N=3 of 14) of the patients receiving pill placebo. Overall rates of treatment completion for the patients receiving emotion-focused psychotherapy, cognitive behavior therapy, imipramine, and placebo were 60%, 47%, 38%, and 13%, respectively. Given the similar low response of panic disorder patients to emotion-focused psychotherapy and placebo, it is of interest that patients treated with emotion-focused psychotherapy were far less likely to drop out of treatment than were those treated with placebo.

Follow-Up Results

At the follow-up visit after 6 months of no treatment, two (15%) of 13 subjects who had responded to emotion-focused psychotherapy relapsed, as did two (22%) of the nine patients who had responded to imipramine; none of the patients who responded to cognitive behavior therapy or placebo experienced a relapse.

Table 2 shows Panic Disorder Severity Scale and Anxiety Sensitivity Index scores of maintenance completers as assessed at follow-up. Anxiety Sensitivity Index scores remained significantly higher in patients treated with emotion-focused psychotherapy.

Discussion

This study comprised a prospective comparison of emotion-focused psychotherapy to proven active treatment in panic disorder patients with no more than mild agoraphobia. Emotion-focused psychotherapy, although equally credible, performed less well than either cognitive behavior therapy or imipramine. Emotion-focused psychotherapy results were similar to those seen with placebo, except that 60% of emotion-focused psychotherapy subjects completed a full course of treatment, whereas only 13% of the placebo-treated subjects completed the study. Emotion-focused psychotherapy used empathic listening and focused on identifying and managing emotions and providing assistance with life problems. We believe that this type of therapy is similar to psychotherapy often provided in the community. Our study failed to confirm efficacy of such an approach for treatment of panic disorder.

These results differed from our findings in a previous study, which did not show a difference between a similar supportive, reflective listening form of psychotherapy and cognitive behavior therapy

(9). The inclusion in the first study of patients with higher levels of agoraphobic avoidance, the use of panic frequency as the main outcome measure, and the lack of a placebo control may have contributed to the difference. The current study is consistent with several other reports that have shown supportive psychotherapy to be less effective than cognitive behavior therapy

(20,

21).

We wish to point out that emotion-focused psychotherapy was not psychoanalytic psychotherapy. Therapists were not trained psychoanalysts, and the treatment differed from panic-focused psychoanalytic psychotherapy

(22). Therapists did not provide genetic or transference interpretations. There was no systematic review of early history. Pilot results of panic-focused psychoanalytic psychotherapy indicate greater change in Panic Disorder Severity Scale scores than we observed with emotion-focused psychotherapy

(23). A randomized, controlled study of panic-focused psychoanalytic psychotherapy is in progress. If efficacy is confirmed, this would suggest that psychoanalytically trained therapists or specific psychoanalytic techniques may be required to treat panic disorder when an approach other than cognitive behavior therapy is employed.

We acknowledge several limitations of this study. First, the small number of placebo patients at our site precluded a within-site comparison. Instead, we used the full four-site complement of placebo-treated subjects to estimate the difference between emotion-focused psychotherapy and placebo. Placebo-treated subjects across the sites were recruited in the same time period and met the same inclusion and exclusion criteria. No site differences were detected. Patients in Pittsburgh had a slightly better placebo response rate than did those across the four sites. Thus, we believe that our results showing no difference between emotion-focused psychotherapy and placebo are likely to be valid.

Another limitation is some heterogeneity in intake procedures. Although we planned to treat emotion-focused psychotherapy subjects during the four-site study, we were unable to enroll sufficient numbers of randomly assigned patients in this way. As a result, we accepted 13 emotion-focused psychotherapy subjects who refused to discontinue medication or refused random assignment. In addition, 10 patients receiving emotion-focused psychotherapy and 14 receiving cognitive behavior therapy were treated in the period immediately after termination of the collaborative study and were randomly assigned to receive only cognitive behavior therapy or emotion-focused psychotherapy (i.e., not imipramine or pill placebo). However, all subjects met the same inclusion and exclusion criteria, and recruitment procedures were the same. Response was not different comparing the three recruitment subgroups.

In summary, emotion-focused psychotherapy proved significantly less effective than medication or cognitive behavior therapy—and performed similarly to pill placebo—in treating symptoms of panic disorder. However, emotion-focused psychotherapy had a markedly lower attrition rate than placebo. If we are correct in assuming that emotion-focused psychotherapy is similar to psychotherapy provided to many patients in the community, our results should serve as a warning that that such treatment may not be optimal. This finding is particularly important in light of the high retention rates. Low attrition in the face of poor response may be related to the avoidant and separation-anxiety behavioral styles reported in these patients

(24). We suggest clinicians attend closely to effectiveness of their treatments, be aware of which treatments are efficacious, and consider learning to administer cognitive behavior therapy.