Sleep disturbances in psychiatric patients are often designated “psychiatric insomnia,” which implies that the insomnia is secondary to the psychiatric distress

(1). Treatment is geared toward psychotherapy or medication, neither of which has been shown to consistently ameliorate sleep disturbances during extended follow-ups in mental health patients

(2,

3). Sedating antidepressants

(2) and psychotherapy

(4) may improve insomnia; however, neither approach targets the psychophysiological conditioning that fuels many insomnia complaints

(3). Psychophysiological conditioning involves attitudes, behaviors, and habits that people adopt regarding their sleep patterns

(2,

3); psychiatric patients with insomnia suffer from this conditioning as well

(1–

3,

5).

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) exemplifies this phenomenon because it involves severe nightmares and insomnia; however, these symptoms rarely receive primary therapeutic attention

(6,

7). In PTSD patients, we know of only one controlled study of treatment for nightmares

(7) and one study of sleep hygiene for insomnia

(8). The lack of treatment research on nightmares and insomnia in PTSD patients is perplexing because effective sleep-oriented therapies for nightmares

(7,

9) and insomnia

(10) have been developed. Nightmares have been successfully treated with cognitive behavior therapies, including desensitization

(11) and imagery rehearsal

(12), which have yielded long-term improvements in nightmare frequency, sleep quality, and psychiatric distress

(13). Efficacy of cognitive behavior therapies in ameliorating insomnia is well documented

(3,

10), even among psychiatric patients

(1,

10,

14). One study demonstrated sustained sleep improvement in a series of patients with depression, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, or somatoform disorders 1 year after treatment

(14). Improvement of insomnia has also been associated with decreased severity of psychiatric symptoms

(2,

15,

16).

To explore the perspective that targeted sleep therapies may lead to better sleep quality and decreased distress

(2,

15,

16), the current study offered sleep treatment to crime victims with PTSD. A small pilot program was developed that combined established techniques

(3,

7,

8,

11–

14) into one treatment protocol for crime victims with nightmares and insomnia. We predicted that successful treatment of nightmares and insomnia would be 1) achieved with a brief group intervention, 2) evident at the 3-month follow-up, and 3) associated with decreases in PTSD, anxiety, and depression symptom severity.

Method

Recruitment and Study Group

The study was approved by the institutional review board of the University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center and was part of an ongoing, free treatment program funded by a direct services grant from the New Mexico Crime Victims Reparation Commission (Victims of Crime Act). Participants were recruited from rape crisis centers or crime victims advocacy groups (21%), mental health centers and private therapists (36%), newspaper articles, television interviews, flyers, and the Internet (36%), and word of mouth (7%). Adults who were 18 years or older who had been victims of a violent crime at least 6 months before enrollment (interval from point of criminal victimization, mean=13 years, SD=13) and who reported weekly episodes of insomnia and nightmares were eligible to participate. Patients who were psychotic, intoxicated, or in a state of alcohol or drug relapse or withdrawal or who had been traumatized less than 6 months before intake were ineligible. After complete description of the study to the subjects, written informed consent was obtained.

Sixty-two participants completed the treatment and the 3-month follow-up: 52 women and 10 men; age, mean=40 years (SD=12). Sixty-one percent were non-Hispanic white, and 29% Hispanic. The participants were victims of sexual assault (48%), physical assault (25%), and other crimes (27%). The majority (76%) reported some form of abuse in childhood or adolescence, including sexual (47%), physical (53%), and/or emotional (75%) abuse. All 62 participants met DSM-IV criteria for PTSD; their PTSD symptom severity was rated as moderate or greater, according to the Posttraumatic Stress Diagnostic Scale

(17). At intake, 66% were concurrently in therapy with mental health professionals.

Ratings

Self-reported validated measures were administered at baseline and at the 3-month follow-up. Higher scores reflect greater symptom severity. The Nightmare Frequency Questionnaire

(18) retrospectively assesses nightmare frequency as nights with nightmares (number of nights with nightmares per week) and actual numbers of nightmares (number of nightmares per week). The Sleep Impairment Index

(3,

16) measures difficulties with sleep onset, sleep maintenance, early morning awakenings, interference with functioning, impairment, concerns about sleep, and sleep satisfaction or dissatisfaction, which yield a total score (range=7–35). Scores higher than 15 reflect clinically significant insomnia, and scores higher than 20 reflect relatively severe insomnia. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index

(19) assesses component scores for sleep quality, sleep latency, sleep duration, sleep efficiency, sleep disturbance, sleep medication use, and daytime dysfunction (sleepiness and fatigue), the sum of which yields a global score (range=0–21). Scores higher than 5 reflect poor sleep quality.

The Posttraumatic Stress Diagnostic Scale

(17) has been validated for monitoring changes in PTSD symptom severity after treatment and contains symptom subscales for intrusion, avoidance, and arousal, which yield a total score (range=0–51). Five categories of PTSD symptom severity are delineated: 0=no PTSD, 1–10=mild PTSD, 11–20=moderate PTSD, 21–35=moderately severe PTSD, and 36 or greater=severe PTSD. The Symptom Questionnaire

(20) measures anxiety and depression symptoms and is a valid and sensitive instrument for discriminating subgroups of psychiatric patients from normal subjects.

Questions from the Nightmare Frequency Questionnaire

(18) and the Posttraumatic Stress Diagnostic Scale

(17) were used to divide the 62 participants into two groups: those with predominantly trauma-related disturbing dreams (N=38; mean=72% [SD=21] of nightmares trauma-related) and those with predominantly non-trauma-related disturbing dreams (N=24; mean=87% [SD=9] of nightmares not trauma-related).

Treatment

Treatment was provided by a sleep specialist (B.K.) and two health educators (L.J. and M.J.H.) working in pairs. The program in use at our facility, the Sleep & Human Health Institute, uses imagery rehearsal for treatment of nightmares (rehearsing images of a changed nightmare), a cognitive imagery approach

(7,

11–

13) that encourages the user to “change the nightmare any way you wish,” according to the model of Neidhardt et al.

(21), and then rehearse the “new dream” while awake. The procedure does not distinguish between traumatic and nontraumatic nightmares, albeit participants are encouraged to select less intense, non-trauma-related disturbing dreams upon learning the technique. Cognitive restructuring is also used because PTSD patients usually link nightmares and trauma inextricably, thus setting up a barrier to change

(7). Accordingly, patients are encouraged

not to discount past trauma but instead to consider that “nightmares that are

trauma-induced may become

habit-sustained.” Patients are taught how to manage unpleasant imagery that may develop while they are practicing pleasant imagery or during imagery of “new dreams.”

For insomnia, sleep hygiene (instruction on sleep habits and behaviors), stimulus control (eliminating learned sleep-preventing associations), and sleep restriction (increasing sleep quality and efficiency by reducing time spent in bed) therapies are provided along with cognitive restructuring to assist patients in identifying beliefs and behaviors that hamper attempts to change sleep habits

(2,

7,

10,

16).

Participants are treated in three weekly sessions and are given a final instruction to change no more than one or two nightmares per week. At the 1-month follow-up, the group meets to assess progress and clarify instructions and current strategies. In the current study, the patients completed posttreatment follow-up by mail 10 weeks after the third treatment session.

Statistical Analysis

Primary outcome variables intercorrelated with mean r=0.40; thus, a repeated measures multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) was conducted with treatment (time) as the independent variable and scores on sleep and distress measures as the dependent variables. A repeated measures MANOVA was conducted to test treatment-by-nightmare type interaction effects to examine distinctions between participants with predominantly trauma-related nightmares and those with predominantly non-trauma-related nightmares. A third repeated measures MANOVA was conducted to test the interaction effects of treatment and change in PTSD ratings to examine distinctions between participants whose PTSD clinical severity improved and participants whose PTSD worsened or stayed the same. Effect sizes were calculated as Cohen’s d. Statistical significance was set at p=0.05.

Results

The overall multivariate effect of treatment was significant (F=18.92, df=5, 57, p=0.0001) for nightmares (number of nights with nightmares per week and number of nightmares per week), sleep quality (score on the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index and the Sleep Impairment Index), and PTSD (score on Posttraumatic Stress Diagnostic Scale) for all 62 participants. The treatment effect for 57 of 62 participants who completed the Symptom Questionnaire was significant (F=7.75, df=2, 55, p=0.001) for anxiety (anxiety score on the Symptom Questionnaire) and depression (depression score on the Symptom Questionnaire).

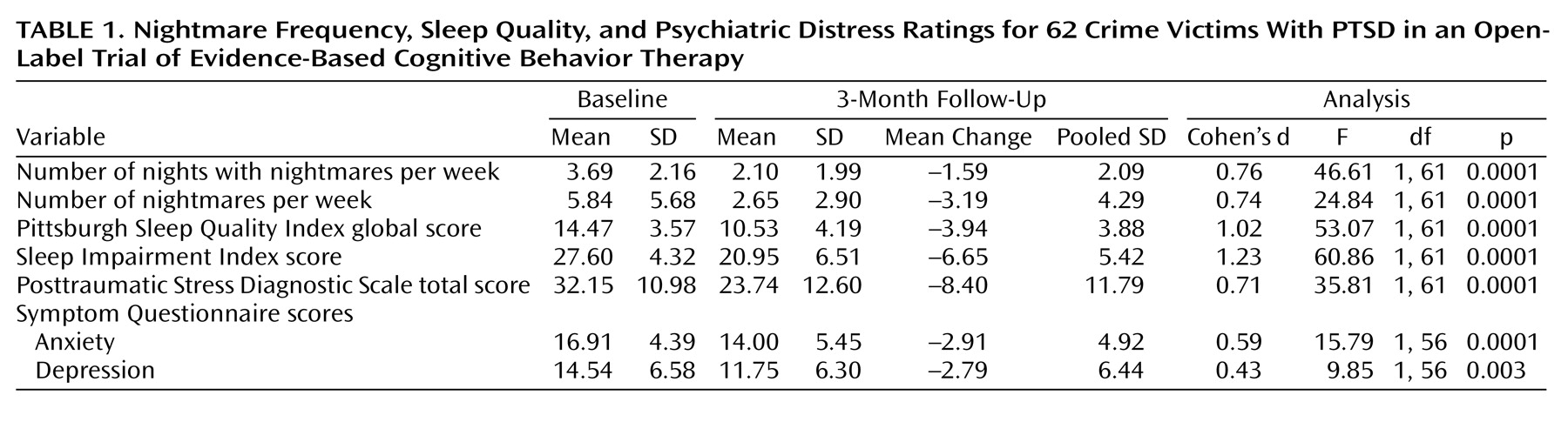

All univariate tests for change in each main variable (demonstrating significant results) and effect sizes (Cohen’s d) are presented in

Table 1. Nightmare frequency reductions were large, roughly equivalent to a change from severe to moderate nightmare frequency. All changes in sleep quality scores were large, roughly equivalent to a change from severe to moderate sleep disturbance. Change in PTSD score was also large, roughly equivalent to a change from the upper end (score∼35) to the lower end (score∼21) of the range of scores that delimit moderately severe posttraumatic stress. Decreases in scores for anxiety and depression were of medium size, indicating a change from extremely severe to borderline severe. No statistically significant moderating effects of treatment were observed for age, ethnicity, duration of PTSD, type of traumatic exposure (sexual assault versus other assaults or crimes), or history of childhood abuse.

Outcomes were compared between those with predominantly trauma-related nightmares (N=38) and those with predominantly non-trauma-related nightmares (N=24). At baseline, the group with traumatic nightmares had worsened severity on all variables, most notably, more than 50% more nightmares, worsened PTSD, and more severe depression (F=4.04, df=7, 51, p=0.001) than the group with non-trauma-related nightmares. However, treatment-by-nightmare type interaction effects did not attain statistical significance (F=2.17, df=5, 56, p=0.07), indicating that both groups experienced substantial improvements on all main variables.

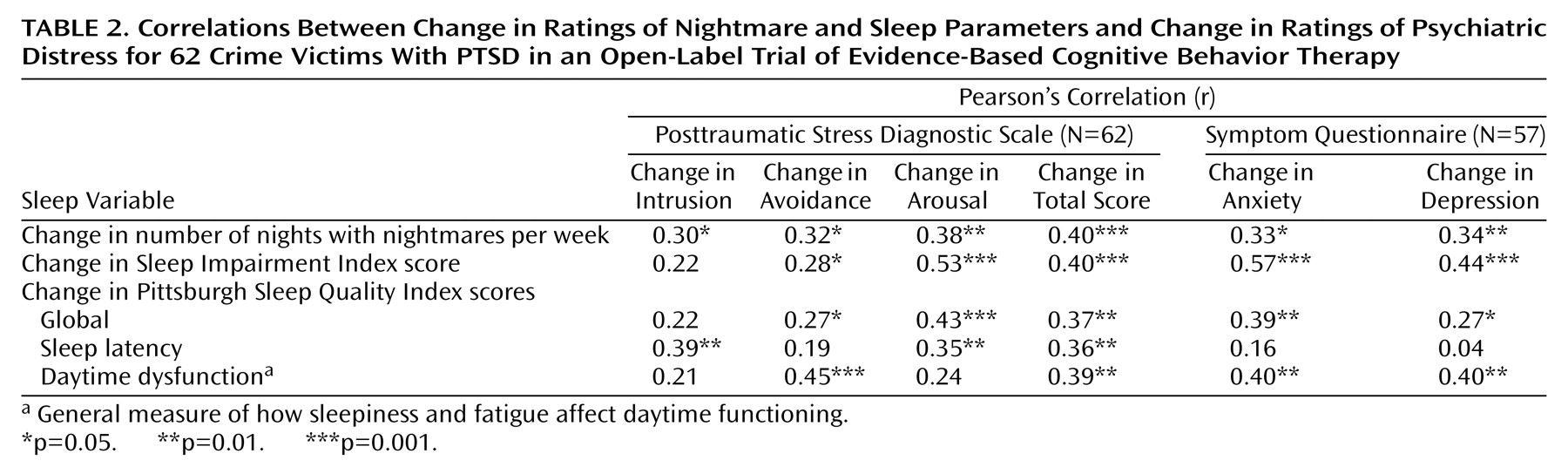

To explore relationships among nightmare frequency, sleep quality, and psychiatric distress, all changes in scores on main variables—and changes in scores on intrusion, avoidance, and the arousal PTSD subscale—were assessed with Pearson’s product-moment correlations (

Table 2). A consistent pattern of significant medium to large coefficients (r=0.27–0.57) was observed for associations between decreases in number of nights with nightmares per week and decreases in scores for all measures of psychiatric distress, as well as for associations between scores for improvement in sleep quality and impairment and decreases in scores for all measures of distress except the PTSD intrusion subscale. A closer inspection of component scores from the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index revealed that decreased scores for sleep latency (time to sleep onset) and improvement in scores for daytime dysfunction (sleepiness and fatigue) yielded the largest and most consistent associations with decreases in scores for some elements of psychiatric distress.

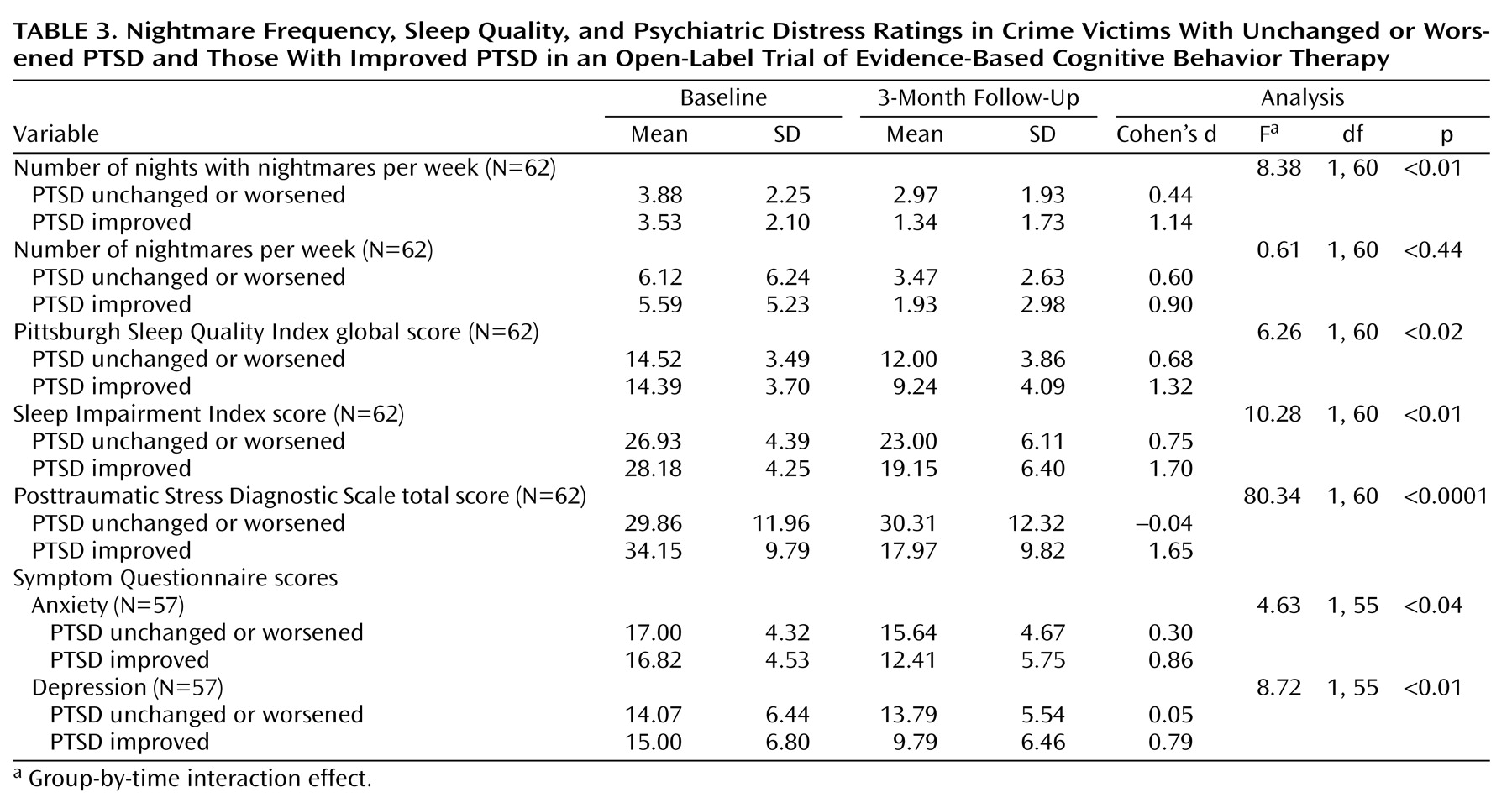

Finally, 79% (N=49) of the patients scored lower on posttraumatic stress ratings at the follow-up. Conservatively, 33 of 62 participants decreased their PTSD ratings by one or more clinical severity levels, according to guidelines for the Posttraumatic Stress Diagnostic Scale (24 decreased their ratings by one level, eight decreased by two levels, and one decreased by three levels), in contrast to 29 patients whose clinical PTSD ratings did not change or worsened (22 were unchanged, six worsened by one level, and one worsened by two levels)

(17). When we compared those with improved PTSD clinical ratings with those whose ratings stayed the same or worsened, significant differences were observed for nightmare frequency, sleep quality, and PTSD ratings (F=15.60, df=5, 56, p=0.0001) and for anxiety and depression scores (F=4.30, df=2, 54, p=0.02). Effect sizes were moderate to large between the two groups for all measures except number of nightmares per week (

Table 3).

Discussion

In this small, within-group, uncontrolled study, crime victims with nightmares, insomnia, and PTSD who averaged 13 years of chronicity demonstrated moderate to large improvements in nightmare frequency, insomnia, and psychiatric distress after receiving evidence-based treatment approaches that 1) deemphasize exposure by avoiding discussion of trauma or traumatic content of nightmares, 2) focus on habitual components of disturbing dreams and sleeplessness, 3) provide no group psychotherapy, 4) offer minimal instruction for dealing with unpleasant imagery, and 5) convey no specific non-sleep-related instructions for managing posttraumatic stress, anxiety, or depressive symptoms. Although the treatment effect cannot be measured in the absence of a control group and issues of causality cannot be addressed, the severity and historical chronicity of disorders in these patients, coupled with their responses to targeted nightmare and insomnia therapies, indicate that the clinical relationship between sleep disturbance and psychiatric distress is very important for some crime victims in this study group.

Decreases in nightmare frequency and insomnia and resultant enhancement in sleep quality are important therapeutic benefits for PTSD patients who suffer unnecessarily from these common symptoms

(6–

8) but of greater interest is the change in their psychiatric distress. Scores on all three distress measures improved, which suggests that improvement in sleep itself is associated with improvement in distress symptoms. In addition, marked contrasts in sleep outcomes between those whose PTSD did and did not improve highlight the potential importance of aggressive treatment for sleep disturbance in applicable crime victims.

Nightmares and insomnia may also factor into psychiatric distress in other ways. In the clinic, PTSD nightmares are perceived as uncontrollable and from the unconscious

(7). However, once successfully treated, patients appear to be imbued with confidence, affording them an opportunity to use imagery rehearsal to help with daytime sequelae. In fact, 37 of 62 participants reported using imagery rehearsal to deal with daytime distress. Nightmares also appear to promote or exacerbate distress during wakefulness

(7,

11–

13). Therefore, treating bad dreams ought to be associated with decreased distress. Distinguishing between trauma-related and non-trauma-related nightmares may not be a critical treatment consideration, whereas decreasing nightmare frequency, or perhaps nightmare intensity, may ultimately prove to be a core component of this therapeutic approach.

Finally, the impact of enhanced sleep quality must be considered. PTSD patients with severe nightmares and insomnia may be discouraged by the absence of a nocturnal respite. Enhanced sleep consolidation might provide patients with psychological benefits

(2,

15) as well as physiological restoration

(5), both of which might favorably influence their levels of distress. Notwithstanding, mean scores for sleep quality and impairment still ranked in the abnormal range in this group of crime victims at their posttreatment follow-up, which is consistent with the emerging hypothesis that other sleep disorders are common in PTSD

(22–

24). A recent case report

(24) indicates that treatment of other sleep disorders may be necessary to normalize sleep patterns in some PTSD patients. In the current study, all distress measures also remained in the abnormal range, highlighting the complex nature of PTSD and the need for multidimensional treatment.

The study was limited by a small group size and the lack of a control group, but it otherwise supports the theory that targeted treatment of sleep problems is associated with improvement in distress. Still, treatment effects cannot be measured without a placebo control. Randomized controlled studies that target sleep-specific symptoms must address these issues. In the interim, PTSD patients with sleep complaints may benefit from treatment options that go beyond conventional psychotherapy or medications, such as evidence-based cognitive behavior therapies for nightmares and insomnia.