Few studies, however, have examined the occurrence of other psychiatric disorders, such as anxiety and adjustment disorders, in the postpartum period

(8,

9). Even fewer have studied postpartum mental illness in Chinese and other non-Western populations

(10–

12). A commonly cited anthropological study

(13) has suggested that postpartum depression is absent in China because of the enriched postpartum social network provided by the family. However, studies making use of self-report postpartum depression screening scales

(14–

20) have yielded widely varying prevalence rates for postpartum depression, ranging from 0% to 18% in various Chinese populations. Our small-scale study

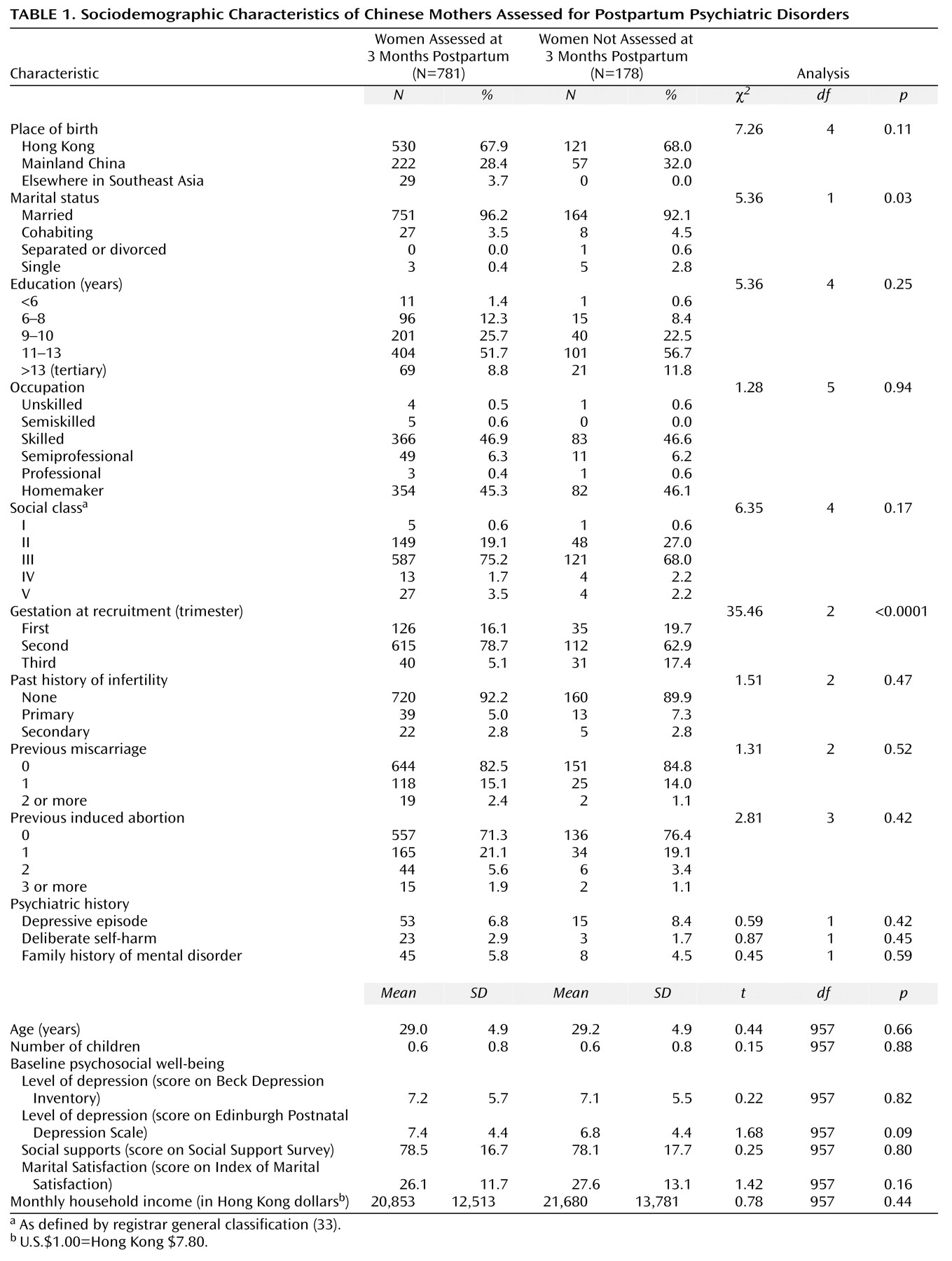

(21) estimated that 12% of recently delivered Hong Kong women suffer from major or minor depression. These divergent findings are partly due to the small and unrepresentative groups employed in many of these studies. In addition, all but the latter study did not use structured clinical interviews or operational criteria in establishing diagnoses. To clarify these contradictory findings, a large-scale study making use of rigorous methodology and representative sampling was clearly necessary.

However, these earlier findings of low rates of depression among Chinese women may no longer be applicable to contemporary Chinese society because of the momentous socioeconomic transformations occurring in the past decades. Since the 1960s, Hong Kong has been transformed from a fishing village-cum-entrepôt into an internationally acclaimed metropolis and financial hub, with a gross domestic product of $23,000 (U.S.) per capita. This rapid industrialization has brought about unprecedented changes in the family structure, gender roles, labor markets, sociomoral values, cultural identity, health, and housing of 6 million people

(25). Even worse, many of these changes ruthlessly intensified in the post-1997 era when Hong Kong was struck by Asia’s economic downturn. In China, profound socioeconomic transformations have also occurred during the past two decades, taking a heavy toll on the social and mental health of the population

(26). Although a population-based epidemiological study will be the ultimate approach to document these changes, a smaller scale epidemiological study within a well-defined context, such as during puerperium, would provide a quick and expedient glimpse of the situation. If we indeed were to confirm that 12% of contemporary Chinese women suffer from postpartum depression, it would support the notion that depressive illness is no longer a rare form of psychiatric morbidity in Chinese populations, and a new wave of population-based psychiatric epidemiological investigations would be in order.

Discussion

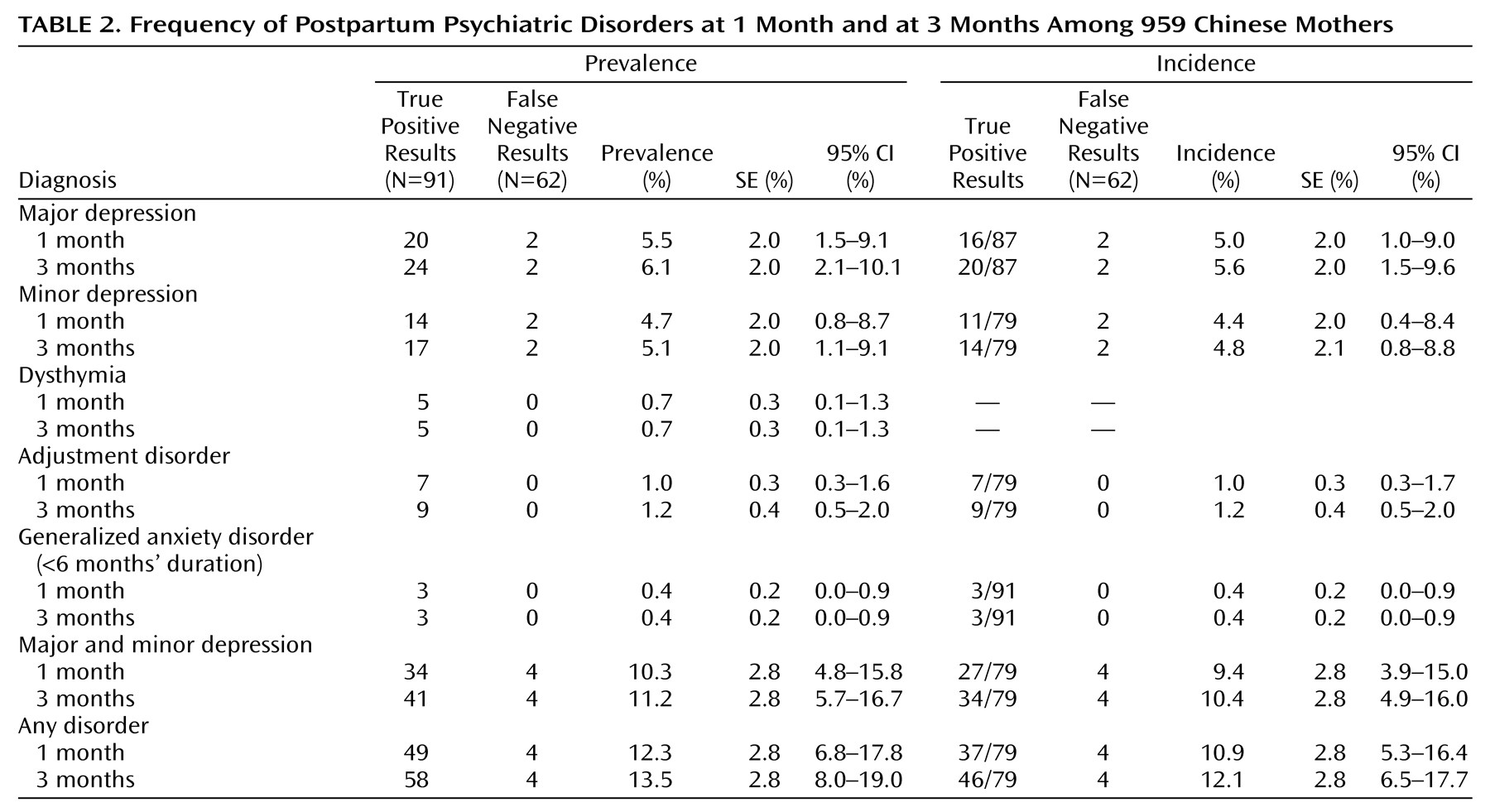

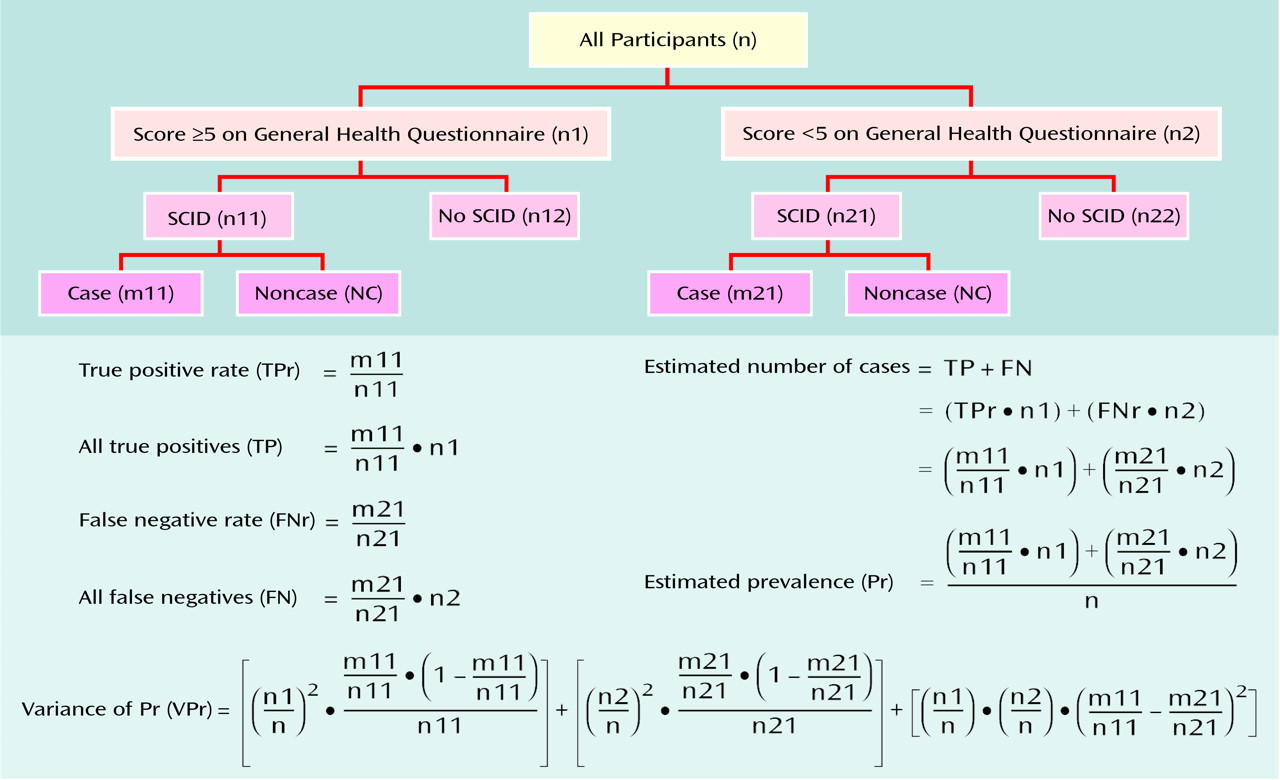

Our study shows that postpartum depression is common among contemporary Hong Kong women. Approximately 6% of our participants suffered major depression and 5% suffered minor depression in the first month postpartum. These figures are similar to our earlier findings

(21). A meta-analysis of 59 studies (including 12,810 women) by O’Hara and Swain

(34) reported a 7% prevalence rate of DSM major depression and an 11% prevalence rate of Research Diagnostic Criteria major and minor depression. Our findings, hence, do not lend support to the notion that Chinese women are immune or protected from postpartum depression. On the contrary, the data suggest that the rate of depression among Chinese women is not different from the rates found among women of childbearing age in Western societies, whether postpartum or not. Obstetricians and psychiatrists should be aware that one in 10 contemporary Hong Kong women in the postpartum period suffers from depressive disorders.

The present study shows that this depressive episode was the first encounter with mental illness in 93% (104 out of 112) of our depressed participants. As such, the women and their families may have had little knowledge of depression and may have misconstrued the mental illness as maladjustment to sleep deprivation, childbearing, and parenthood. Fear of stigmatization and psychological denial may further delay these women from seeking proper treatment. For these reasons, and the fact that the onset of postpartum depression is synchronized to a well-defined time point, a universal screening program would be tremendously useful to diagnose depression in postpartum women.

Nowadays, postpartum depression is so powerful and dominant as a diagnostic category that it overshadows research on other postpartum psychiatric disorders, such as anxiety or adjustment disorders. Although the present study confirms that depression is indeed the predominant form of psychiatric morbidity in the postpartum period, it also suggests that generalized anxiety disorders, dysthymia, and adjustment disorders are also present in the postpartum period. Inasmuch as these disorders are rather rare (i.e., with 3-month prevalences of about 1%), a large-scale study is necessary to collect adequate data for meaningful analysis of the specific characteristics, etiologies, treatment responses, and long-term outcomes of these disorders. Before information from such studies is available, clinicians should remain vigilant for these relatively uncommon forms of morbidity in postpartum women.

Several limitations of this study deserve special discussion. First, 19% of the participants were not included in the 3-month assessment. Although the participants who were not included were not different from those who responded to the diagnostic interview in terms of sociodemographic or psychiatric characteristics, they were more likely to be of later gestation at recruitment. Second, about 40% of the eligible women declined to participate in the study, and only limited sociodemographic data were available from these nonparticipants to evaluate the potential bias they may have introduced. Third, although the average rate of miscarriage is 10%–15% of all pregnancies in the general population, only 2% of our participants had a miscarriage during the study. Instead of reflecting a sampling bias, this was probably due to the fact that majority of the participants joined the study after their first trimester, when most miscarriages occur.

Previous studies have shown that a past history of depression, including a past postpartum episode, increases the risk of postpartum depression. Our data, however, showed that previous depressive episodes were present in only approximately 7% of the cases of postpartum depression. We speculate that this low rate is related to the low fertility rate of Hong Kong women. At present, the average number of children per Hong Kong family is close to one. Because most women, including our participants, have only one child in their lifetimes, they do not have any past postpartum depressive episodes. This may partly explain why a past history of depression is rare even among the participants who had postpartum depression. Finally, because the present study was conducted among Hong Kong women, further replications in other regions of China are necessary.

The findings of the present study should be read in the wider context of psychiatric epidemiology among the Chinese. Our data suggest that the lifetime prevalence of major depression in contemporary Hong Kong women of reproductive age is at least 6%, several-fold higher than the age- and gender-matched lifetime prevalence (0.9%–2.5%) reported by the aforementioned population-based epidemiological studies

(22,

23). In the present study, precautions were taken to ensure sample representativeness. The validity of the findings is also enhanced by the use of a standardized and internationally recognized research design, diagnostic instrument, and set of classificatory criteria. Hence, the higher rate of depression in contemporary Hong Kong women requires other explanations.

First, it is possible that the prevalence rates of depression were underestimated in previous epidemiological surveys because of cross-cultural discrepancies in diagnostic concepts and practices. Neurasthenia, a nosological concept that has largely disappeared in Western psychiatry, is still commonly employed by Chinese psychiatrists. Kleinman

(35) has shown that the Chinese concept of neurasthenia overlaps substantially with that of DSM nonpsychotic depression. However, in mainland Chinese epidemiological surveys, neurasthenia (prevalence of 8%–14%) has not been counted toward the overall rates of depression

(36,

37). In the epidemiological surveys conducted in Hong Kong and Taiwan, the research instruments were not modified to enable diagnosis of neurasthenia

(22,

23). All of these practices may contribute to an underestimation of the overall prevalence rate of depression in Chinese populations.

Alternatively, there may be a genuine increase in the prevalence rate of depression in Chinese societies. Traditional values and sociocultural factors, such as family cohesiveness, a low divorce rate, and parental substitutes, have often been cited to explain the low rates of all depression in Chinese studies from the 1980s

(22,

23). However, these putative protective factors may no longer be relevant, as we have seen divorce, family violence, job insecurity, child and sexual abuse, juvenile pregnancy, deterioration in network solidarity, and alcohol and drug addiction invade the nuclear family in recent times

(26). China now has the highest suicide rates in the world among elderly people and young women

(38). The past two decades of epidemiological studies in China have also shown that the prevalence of affective disorders has been consistently rising

(39). As Chinese societies are steadily Westernized and urbanized in the process of profound socioeconomic transformation, it is possible, and indeed commonsensical, that the observed pattern of psychiatric morbidity in Chinese communities will be moving closer to those seen in the West. Although our findings and interpretations should be treated as preliminary, a new wave of psychiatric epidemiological studies of Chinese populations is certainly in order.