In the context of renewed attention to ethical and regulatory issues in human subjects research, it is striking that few data from treatment research subjects are available to inform this discussion

(1). Such data are necessary for developing guidelines that ensure both the protection of human subjects and the integrity of research methods while avoiding unnecessary and burdensome procedural obstacles to clinical studies.

In particular, since clinical trials to study the efficacy or effectiveness of a treatment depend on recruitment of large numbers of patient participants

(2,

3), the perceptions of both potential subjects and practicing clinicians toward research may be critically important to progress in clinical science. For example, many therapists believe that the evaluation and assessment procedures necessary to conduct methodologically rigorous outcome research distort the treatment process. To the extent this is true, generalization of results would be limited. If such views are unfounded, however, they represent a resistance to research and a major obstruction of the advancement of knowledge.

To address these issues, we developed a study in which research patients and clinicians were systematically surveyed to assess their experience of data collection procedures. The primary study was an empirical examination of the feasibility of studying outcome in our long-term psychodynamic psychotherapy and psychoanalysis clinics

(4,

5).

In a search of the literature, we could identify no instrument that systematically assessed patients’ experiences in treatment research. A survey questionnaire was therefore developed in consultation with psychodynamic clinicians to assess and quantify commonly expressed concerns about research participation and its purported effect on treatment.

Method

The primary study, described elsewhere

(4,

5), was developed to assess the feasibility of studying outcome in long-term psychodynamic and psychoanalytic therapies. Patients were treated in twice-weekly psychodynamic therapy with residents in psychiatry or in psychoanalytic treatment with candidate analysts. Research procedures included structured diagnostic interviews with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (axis I and II)

(6) and the Social Adjustment Scale

(7), use of 10 self-report forms

(4) requiring approximately 1.5 hours to complete, and audiotaping of five consecutive therapy sessions. The baseline evaluation was repeated after 1 year of treatment.

The survey questionnaire we developed, entitled Assessing the Impact of Research on Subjects, is a 14-item (baseline evaluation) or 19-item (final evaluation) self-report questionnaire that uses a Likert-type scale to assess positive and negative emotional and cognitive appraisals of the experiences of undergoing a structured interview, completing questionnaires, and having sessions audiotaped. Positive items asked whether questionnaires and structured interviews promoted self-realization or facilitated the treatment. Negative items asked whether questionnaires and interviews seemed disruptive or intrusive. Audiotaping items asked about difficulty adjusting to audiotaping. The therapists’ questionnaire assessed the therapist’s perception of the patient’s experience and used wording that was identical to the patients’ version wherever possible.

The survey questionnaire was mailed with an addressed, stamped envelope to the patient and corresponding therapist within 1 week of the completion of the fifth audiotaped session at baseline, and within 1 week of the completion of structured interviews and self-report questionnaires at the 1-year evaluation. Institutional review board approval and written informed consent were obtained, and no monetary reimbursement was provided to patients.

Repeated measures analysis of variance or paired t tests, as appropriate, were used to investigate whether there were group differences at baseline and at 1 year, to assess for change over time, and to look for interaction effects.

Results

Twenty-three of 36 patients (63.9%) who were approached agreed to participate in the feasibility study, and all patients remaining in treatment elected to continue in the study at 1 year (N=15). Nineteen of the 23 patients (82.6%) were female, the mean age was 27.4 years (SD=7.9), and 18 (78.3%) had never married. All had at least some college education. Sixteen (69.6%) were Caucasian, three (13.0%) Asian, two (8.7%) black, one (4.3%) Hispanic, and one (4.3%) East Indian. The majority of patients (N=15, 65.2%) met lifetime criteria for an affective or anxiety disorder. There were no differences on demographic or survey variables between those who dropped out of treatment (N=8) and those who remained the full 1-year period (N=15).

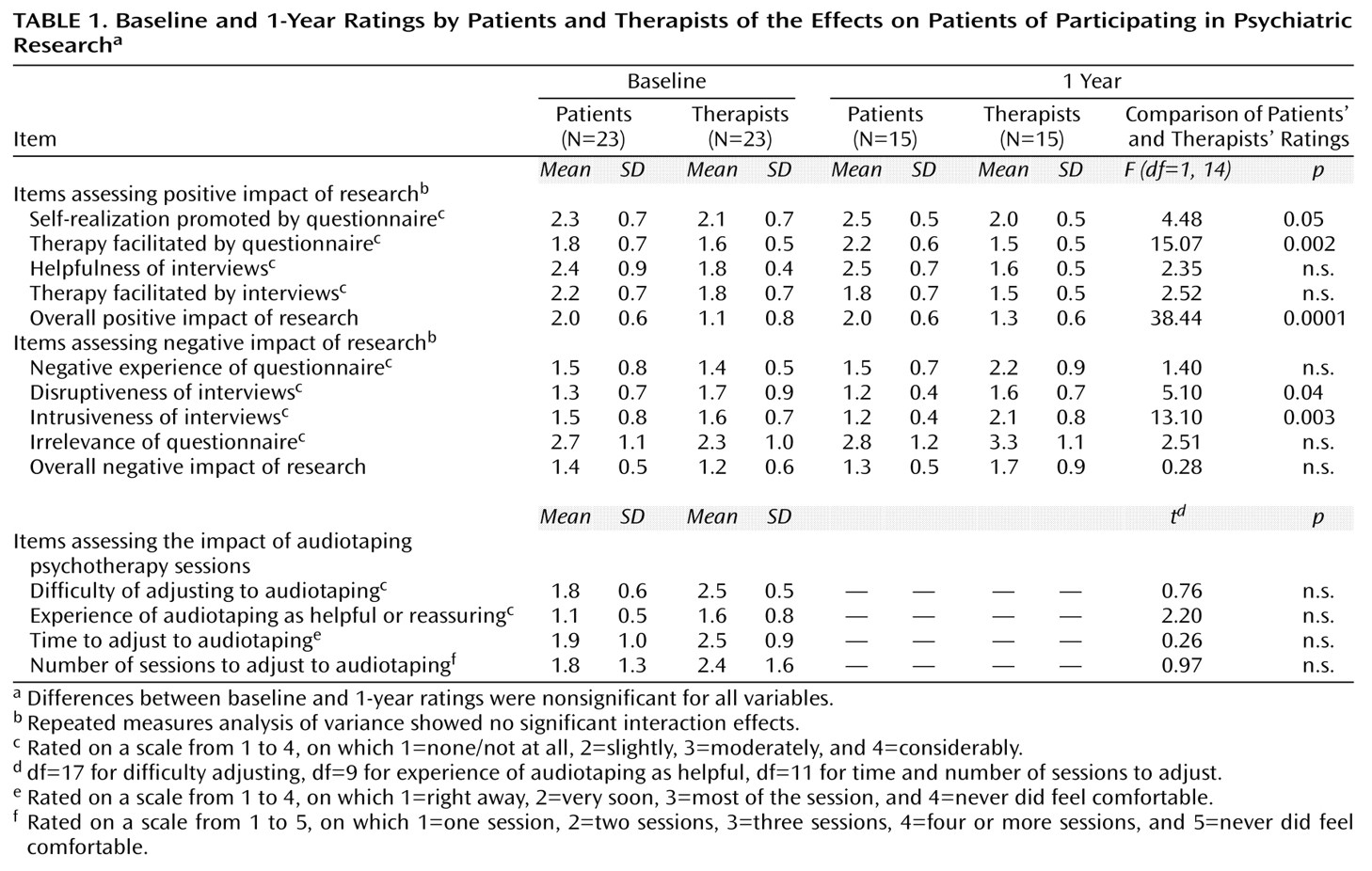

At baseline, patients rated both self-report questionnaires and structured psychiatric interviews as slightly to moderately helpful in promoting new insight about themselves and slightly to moderately helpful in facilitating therapy (

Table 1). Questionnaires and interviews were rated as not at all to slightly intrusive and disruptive and, overall, as a slightly negative experience (

Table 1). Patients rated the research as only slightly to moderately unnecessary or irrelevant to treatment. Adjustment to audiotaping of sessions occurred within two sessions and very soon after sessions began (

Table 1).

There was no statistically significant change between baseline and 1-year ratings for patients or therapists on any variable.

Therapists’ ratings of the overall positive impact of research on patients were significantly lower than the patients’ self-report ratings of the positive impact of research. The same pattern was seen on ratings of whether and to what degree questionnaires promoted self-realization and facilitated therapy (

Table 1). Patients’ assessments of whether structured diagnostic interviews were disruptive and intrusive were significantly less negative than therapists’ assessments (

Table 1). Patients and therapists did not differ on their ratings of the experience of tape-recording the sessions (

Table 1).

On a question about the informed consent process, which asked whether patients felt well informed before participating, most patients (nine of 15) reported feeling they were well informed, three were not sure, and three answered “no” to this question. However, nearly all patients (14 of 15) who completed the study stated they would definitely or probably participate if they had it to do over again.

Discussion

Our main finding was that patients enrolled in a psychodynamic psychotherapy research study reported minimal negative impact from participating in research, and a slight to moderate positive impact. The research procedures in the study (questionnaires, interviews, and tape recording of sessions) are commonly used in clinical trials. Furthermore, clinicians underestimated the positive benefit of research participation to patients and overestimated the intrusive and disruptive aspects of the research, compared to patients’ ratings. No patients who continued in treatment dropped out of the research, and the dropout rate was comparable to that observed in other clinical trials of psychosocial or medication treatments (eight of 23 patients, 34.8%). Our clinical trial findings complement those from a large descriptive study of psychological trauma in which almost all participants reported minimal negative reactions to the research procedures and found participation somewhat useful

(8).

Confidence in the results of this study is limited by two factors: 1) a relatively small sample size, which can be addressed in future studies, and 2) the use of a new instrument that lacks established test-retest reliability or construct validity. The sample size limits interpretation of nonsignificant findings in particular.

This study pertains to subjects who volunteer for research participation. The potential experience of those who declined to participate is unknown, but irrelevant, since informed consent is designed to allow individuals who might find research too burdensome or intrusive to decline participation. The fact that, at the conclusion of the study, some patients reported that they did not feel well informed can have several interpretations. Patients may not have fully understood explanations of the study during the informed consent procedures, or the informed consent procedures may not have been adequate. Alternatively, verbal descriptions may have a limited capacity to fully communicate in advance such a complex experience as research participation. However, the willingness of nearly all patients to participate again shows that those aspects of research that might be experienced as burdensome were well communicated through the informed consent procedures, and provides reassurance about the ethical integrity of these procedures.

The results of this study have several implications. First, we found that it was feasible to study research subjects’ experiences. Such data are critical in informing discussions about research ethics. Second, patients reported minimal negative reactions, despite participating in a fairly intensive assessment that included audiotaping of sessions and approximately 2.5 hours of diagnostic interviews. Third, patients reported a positive benefit that was due to the research methodologies themselves, a possibility that is rarely mentioned in discussions of research practices. Fourth, clinicians significantly underestimated the positive benefits of research participation for patients and overestimated the negative aspects. This finding suggests that therapists’ assessments of their patients’ experience in research were, not surprisingly, influenced by their own attitudes. The belief held among some therapists that research is necessarily intrusive and harmful was not supported by our data.

In fact, a few prior reports on the impact of research participation on clinical outcome found that its effects ranged from negligible to significantly positive

(9–

11). These findings are especially important, as it is our impression that resistance to research based on such objections has impeded progress specifically in the study of psychodynamic psychotherapies.