Norepinephrine is one of the major central nervous system (CNS) effectors of the human stress response. Its potential role in the pathophysiology of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD)—a syndrome intrinsically related to the experience of extraordinary stress—has been under direct investigation with modern techniques for more than a decade

(1). Although the clinical data, in aggregate, indicate that patients with PTSD have exaggerated CNS responses to noradrenergic activation by means of antagonism of the presynaptic α

2 autoreceptor

(2–

4) and have noradrenergic systems that are hyperresponsive to a variety of stimuli

(5–

9), the situation in the CNS during the baseline or unstressed state has remained unclear because there are so few data.

Evaluation of both plasma and urinary norepinephrine concentrations in patients with PTSD under “resting” conditions has been repeatedly performed. Some, but not all, of these studies have observed elevated baseline urinary excretion of norepinephrine

(10–

17), and plasma levels (or levels of the norepinephrine metabolite 3-methoxy-4-hydroxy-phenylglycol [MHPG]) have most often, but certainly not always, been found to be normal or even reduced at baseline

(2,

6–

9,

18,

19).

To our knowledge, no direct measures of CNS norepinephrine in PTSD have been reported until now. The evaluation of CNS norepinephrine levels is important because noradrenergic activity in the periphery does not necessarily mirror that in the CNS

(20). For example, norepinephrine in plasma and in CSF are derived from largely, but not completely

(21), disparate sources; therefore, dissociation between peripheral and CNS norepinephrine concentrations can take place

(22–

24).

We used the technique of serial CSF sampling over several hours through an indwelling spinal canal subarachnoid catheter to test the hypothesis that CSF norepinephrine concentrations are tonically elevated in patients with chronic PTSD. Neurochemicals in CSF are among the most accessible indexes of CNS activity in the human. CSF, which bathes the brain and provides the microclimate necessary for neuronal function, appears to be physiologically involved in both synaptic and nonsynaptic information processing in the CNS. The use of a flexible, indwelling subarachnoid catheter permitted us to wait for the stress of the lumbar puncture procedure and spinal canal catheterization to resolve before sampling CSF

(25). Thus, the norepinephrine levels obtained were more reflective of baseline status than a stress-induced state.

Method

Subjects

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Cincinnati Medical Center and the Research Committee of the Cincinnati Veterans Affairs (VA) Medical Center. Informed written consent was obtained from each patient or volunteer before their participation.

We studied 11 male patients with chronic PTSD and eight healthy men. The healthy men were carefully screened by using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID)

(26) and unstructured exploratory clinical interviews to exclude those with current or past psychiatric disorder or a history of psychiatric disorder in first-degree relatives. The comparison subjects’ mean age was 41 years (SD=9, range=23–50), and their mean body mass index was 25.4 kg/m

2 (SD=4.0). All of these subjects were medication free and without health problems. Three of eight normal comparison subjects smoked cigarettes until the evening before the study.

The mean age of the 11 patients with PTSD, who were also given the SCID, was 42 (SD=9, range=23–49), and their mean body mass index was 29.0 kg/m

2 (SD=3.6). All 11 patients had suffered severe combat-related trauma, nine in Vietnam and two in Iraq during Desert Storm. Six of the 11 patients had histories of alcohol or drug abuse but had been abstinent from substances of abuse (excluding tobacco) for, respectively, 15, 10, 7, 2.5, 1.4, and 0.5 years before study. Urine toxicology screens documented abstinence. Six of the patients smoked cigarettes until the night before the CSF withdrawal procedure. None of the patients was clinically depressed at the time of study, but six had histories of major depression (all unipolar, with the exception of one bipolar II). Seven patients had taken psychoactive medication in the past but had discontinued all medications at least 14 half-lives before study. The patients’ mean score on the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale

(27), administered the day before CSF sampling, was 82 (SD=22).

Procedures

Continuous collection of CSF

Subjects followed a controlled low-monoamine diet for at least 3 days before admission to the Psychobiology Research Unit at the Cincinnati VA Medical Center. They were given a standard 667-calorie preload meal (20% protein, 24% fat, and 56% carbohydrate) at 8:00 p.m. the evening before the study began. Participants fasted thereafter but were permitted to drink water and smoke tobacco until midnight. The next morning, a 20-gauge catheter was placed in the lumbar subarachnoid space at approximately 8:00 a.m. as described elsewhere

(28). At 11:00 a.m., approximately 3 hours after subarachnoid catheter placement, continuous CSF withdrawal into iced test tubes was begun at a rate of 0.1 ml/minute. The total volume of CSF withdrawn was less than 10% of the normal daily volume of CSF produced. Normal saline solution was infused (100 ml/hour) throughout the experiment through a catheter that had been inserted the night before into an antecubital vein in the nondominant arm. Blood was withdrawn into iced glass test tubes at intervals through an intravenous catheter that had been placed in the dominant arm the night before the CSF withdrawal procedure; plasma was harvested near the bedside and frozen. All subjects fasted throughout the experiment; no smoking was permitted. A Critikon Dinamapp Vital Signs Monitor (Critikon, Inc., Tampa, Fla.) mechanically took heart rate and blood pressure from the left lower leg every 1.5 hours, beginning at 11:00 a.m.

High performance liquid chromatography

CSF was frozen at –80°C until immediately before assay. Each tube of CSF (or plasma) was assayed for norepinephrine in duplicate by using an ESA (Chelmsford, Mass.) high-performance liquid chromatography system with electrochemical detection. This system included a refrigerated autosampler. A previously described method was used with minor modifications in the detector electrode settings, mobile phase, and pH

(29). Ten microliters of CSF were injected at a time. Plasma was deproteinized before injection. Intraassay and interassay variability for CSF norepinephrine averaged 4.4% and 5.9%, respectively. For plasma norepinephrine, intra- and interassay variabilities were 7.8% and 8.0%.

Statistical Analysis

The CSF norepinephrine time series of patients and comparison subjects were compared by using a one-way repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) with six within-group levels (hourly CSF norepinephrine levels over 6 hours per subject) computed on Stat-View 5.01 software (SAS Institute, Cary, N.C.). For the ANOVA, the data were also log-transformed, but the results did not differ, so only the analysis of raw values is presented. To reduce the influence of outliers, when present, on the statistical results, we used the Mann-Whitney U test and calculated exact p values to compare average plasma norepinephrine concentrations and blood pressure readings between groups. Otherwise we used two-tailed Student’s t tests, as appropriate. Pearson coefficients were used in the correlation analysis. Values of p<0.05 were considered significant.

Results

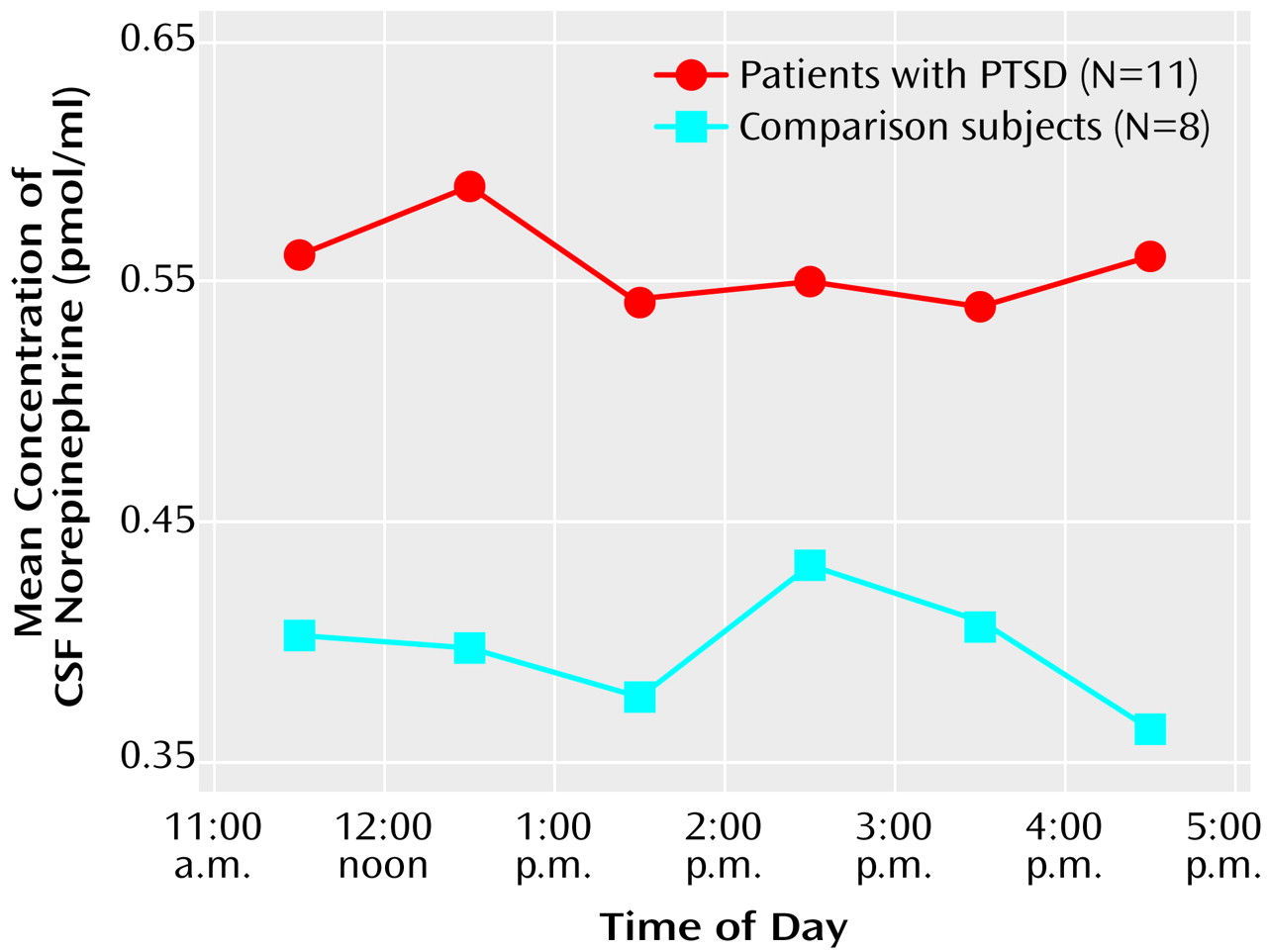

CSF norepinephrine levels were obtained hourly and were significantly higher in the patients with PTSD than in the normal comparison subjects (F=4.49, df=1, 17, p<0.05) (

Figure 1). When the ANOVA was performed on log-transformed data, the results were even more significant. The mean CSF norepinephrine level in the patients with PTSD was 0.55 pmol/ml (SD=0.17), but the mean CSF norepinephrine level in the normal comparison subjects was 0.39 pmol/ml (SD=0.16). The median CSF norepinephrine levels were 0.54 and 0.32 pmol/ml in the patients with PTSD and the normal comparison subjects, respectively.

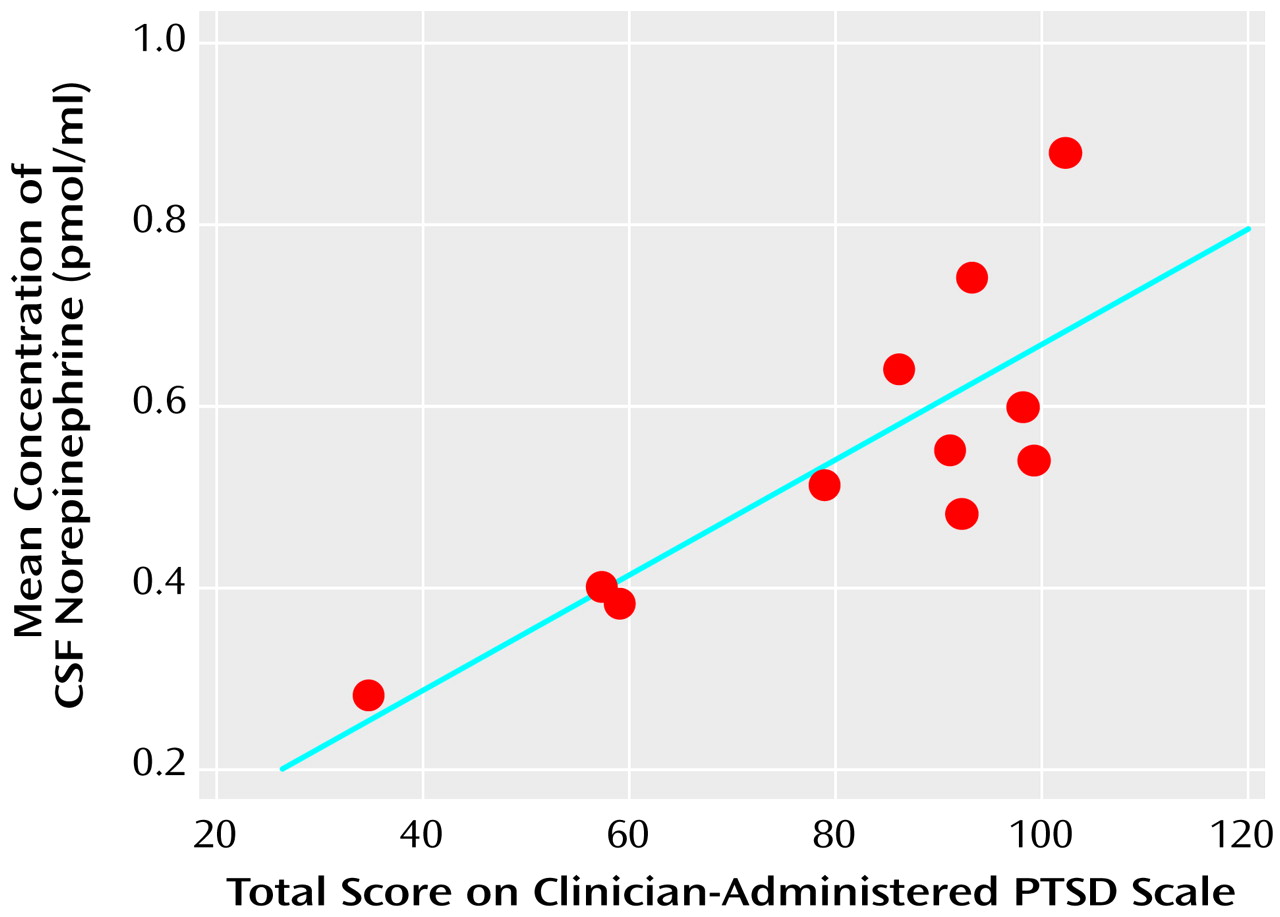

The mean CSF norepinephrine concentrations correlated positively with the total Clinician-Administered PTSD scores in the patients with PTSD (r=0.82, df=10, p<0.005) (

Figure 2). The correlation between mean CSF norepinephrine and the avoidance subscale of the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale was positive and significant (r=0.79, df=10, p=0.004), and nonsignificant positive correlations were observed for both the intrusion (r=0.57, df=10, p=0.07) and the hyperarousal (r=0.54, df=10, p=0.09) subscales.

From one to eight plasma norepinephrine levels were obtained for nine of the patients with PTSD and all eight of the normal comparison subjects at various times (mean=four per subject). The mean plasma norepinephrine levels were 1.78 pmol/ml (SD=1.50) and 0.92 pmol/ml (SD=0.29) in the normal subjects and patients with PTSD, respectively (exact p=0.38). No significant correlation between mean plasma norepinephrine levels and the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale scores were present (for the total Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale score, r=–0.32, df=8, n.s.).

Systolic blood pressure was significantly higher in the patients with PTSD (mean=122.6 mm Hg, SD=10.8) than in the healthy comparison subjects (mean=112.7 mm Hg, SD=21.6) (exact p=0.01). Mean diastolic blood pressure was 74.9 mm Hg (SD=5.3) in the patients with PTSD and 69.3 mm Hg (SD=8.0) in the normal comparison subjects (exact p=0.09). Mean heart rate was 63.2 bpm (SD=7.3) in the subjects with PTSD and 61.6 bpm (SD=5.0) in the normal comparison subjects (t=0.53, df=16, p=0.60).

Discussion

These results reveal not only that baseline CNS noradrenergic tone is higher in patients with chronic PTSD than in healthy comparison subjects but also that this pathophysiologic finding is directly related to the severity of the disorder’s clinical manifestations. The elevated baseline CSF norepinephrine concentrations are consistent with a sustained hyperactivation of CNS fear-related neurocircuits in PTSD

(30) even in the absence of a specific stressor—although we cannot rule out the possibility that confinement to a hospital bed for several hours before and during CSF withdrawal constituted a type of restraint stress. Whether the hyperfunction of CNS norepinephrine in PTSD is a cause or consequence of traumatic stress remains unknown. If trauma-induced, it is remarkable that the apparently elevated baseline noradrenergic drive is present years—up to three decades—after traumatization and the onset of PTSD.

In contrast to the CSF results, the plasma norepinephrine concentrations in our patients with PTSD were similar to or lower than those found in the healthy comparison subjects and show no evidence of a positive relationship with PTSD symptoms as measured by Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale scores.

The elevated CSF norepinephrine levels in our combat veterans with PTSD occurred within the context of elevated CSF concentrations of another major effector of the CNS response to stress, corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH). Elevated CSF concentrations of CRH were previously reported in these same patients

(31). However, unlike the situation with CSF norepinephrine, CSF CRH concentrations were not significantly related to PTSD symptoms as measured by Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale total and subscale scores

(31). Elevated CSF levels of both norepinephrine and CRH are also observed in severely depressed, melancholic patients

(32), but hypercortisolemia is present as well in melancholically depressed patients, whereas patients with PTSD—including the present subjects during CSF sampling

(31)—usually, albeit with exceptions

(12,

14,

15), do not show hypercortisolemia or elevated excretion of urinary free cortisol (see reference

33 for review). Thus, at least at baseline, patients with chronic PTSD uniquely manifest hyperactivation of stress-responsive neurohormones in the CNS without commensurate stress system activation in the periphery.

These data demonstrating baseline CNS noradrenergic hyperactivity in patients with chronic PTSD provide strong support for the evaluation of treatment interventions that reduce or normalize norepinephrine-mediated neuronal signaling—such as α

1- and β-adrenergic receptor antagonists, presynaptic α

2-adrenergic agonists, or—hypothetically—norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors

(1,

34). If subsequent work validates the present findings, CSF norepinephrine levels may prove useful to consider when diagnostically evaluating patients or when monitoring their responses to attempted treatments for PTSD.