At the dawn of the 21st century, vascular dementia, the second most common cause of dementia after Alzheimer’s disease, remains a diagnostic challenge

(1–

4). Several sets of clinical criteria have been proposed to decrease the considerable subjectivity and disagreement among clinicians in establishing the diagnosis of vascular dementia. However, their use has led to marked variability among reported incidence and prevalence rates

(5) as well as substantial differences in the clinical classification of cases of dementia

(6–

10). There are several reasons for this phenomenon: the complex and uncertain time relationship between the onset of dementia and brain ischemia, the ambiguous significance of focal neurological signs, and, most important, the frequent coexistence of degenerative and vascular pathology in the aged brain

(11).

Currently used clinical criteria for vascular dementia include, among others, those proposed by DSM-IV, ICD-10, the State of California Alzheimer’s Disease Diagnostic and Treatment Centers (ADDTC)

(6), and the National Institute for Neurological Disorders and Stroke–Association Internationale pour la Recherche et l’Enseignement en Neurosciences (NINDS-AIREN)

(12). Surprisingly, there are very few data comparing the application of these criteria with neuropathological findings.

In a previous study

(13), we found that the ADDTC criteria for possible vascular dementia were more sensitive than the NINDS-AIREN criteria. To date, there is no neuropathological validation of the ADDTC and NINDS-AIREN criteria for probable vascular dementia. This is also the case for the widely disseminated DSM-IV and ICD-10 criteria for vascular dementia. To address this issue, we performed a clinicopathological study of the cases of 89 autopsied patients with dementia and report the sensitivity and specificity of the four sets of criteria.

Method

The autopsy series consisted of 89 patients with dementia from the University of Geneva Hospitals Belle-Idée. Patients were included if they had been clinically evaluated, including neurological and mental status examinations and head computerized tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), within 6 months of their death. A neuropsychological assessment, as fully described elsewhere

(14), was performed in all cases and included testing of memory, orientation, language, visuospatial and visuoconstructive abilities, abstract thinking, and judgment. Patients with major neuropsychiatric illness, alcoholism, or Parkinson’s disease were excluded. The dementia rate was 30% for the general hospital population and 35% for autopsied patients. Autopsies were obtained by the house staff in 33% of deceased patients. The mean age for hospitalized patients was 84 years, and 70% were women; the mean age for deceased patients was 86 years, and 61% were women; the mean age for autopsied patients was 85 years, and 62% were women.

Brains were fixed in a 15% formalin solution for at least 6 weeks and cut into 1-cm-thick coronal slices. Macroscopic infarcts were identified on coronal levels separated by 1 cm throughout the entire brain. For microscopic purposes, paraffin-embedded blocks were cut into 6-μm-thick sections and were stained with hematoxylin-eosin and cresyl violet according to Holzer and Globus silver impregnation techniques

(15). Microscopic infarcts were identified and dated on two adjacent sections for each level with hematoxylin-eosin and cresyl violet stains. In addition, tissue blocks were taken from the hippocampal formation, including the entorhinal cortex, the superior and middle frontal cortex, the superior, middle, and inferior temporal cortex, the inferior parietal cortex, the primary and secondary visual cortex, and the midbrain, including the substantia nigra.

To visualize Alzheimer’s-disease-type lesions, additional sections were stained immunohistochemically with highly specific and fully characterized antibodies to the microtubule-associated protein tau and to the core-amyloid β protein A4. Characterization and specificity of these antibodies have been fully reported elsewhere

(16,

17). Briefly, 6-μm-thick sections were incubated overnight with either anti-tau antibody or the anti-β A4 antibody, both at a dilution of 1:4000. Following incubation, sections were processed by the peroxidase-antiperoxidase method with 3,3′-diaminobenzidine as a chromogen.

Cases were classified neuropathologically as either vascular dementia, Alzheimer’s disease, or mixed dementia. All cases of Alzheimer’s disease were confirmed by using the National Institute on Aging-Reagan criteria

(18). Cases of vascular dementia were identified by the presence of multiple macroscopic and microscopic cortical infarcts or the lacunar state, which involved three or more neocortical areas exclusive of the primary and secondary visual cortex sampled from at least three of the coronal 1 cm-thick levels described. Vascular lesions confined to subcortical structures were not considered for the diagnosis of vascular dementia. Microscopic confirmation of the neuropathological diagnosis was based on ischemic changes such as focal neuronal loss and astrogliosis in the area of microinfarcts. No or minimal neurofibrillary tangle and senile plaque densities and no Lewy and Pick bodies or other pathological lesions were found in cases of vascular dementia. Cases that satisfied both National Institute on Aging-Reagan criteria for probable Alzheimer’s disease and the criteria for vascular dementia were classified as mixed dementia.

All histological examinations were performed by the same neuropathologist, and all inpatient charts were reviewed by one physician who was blind to the neuropathological diagnosis. All cases were later reviewed by a second clinician and a second neuropathologist to determine interrater reliability. Measured by the kappa statistic, interrater reliability ranged from 0.82 (ICD-10) to 0.93 (ADDTC) for the sets of clinical criteria and was 0.96 for the neuropathological diagnosis. Discrepancies among the clinical raters were examined by three experienced senior clinicians (J.-P.M., P.G., G.G.) and resolved by consensus in all cases.

The clinical criteria applied have been described in detail elsewhere

(19). Briefly, the ADDTC and NINDS-AIREN criteria both require the presence of dementia, evidence of cerebrovascular disease, and, according to the level of certainty (possible or probable), a relationship between the two. The ADDTC definition of dementia requires two impaired cognitive domains but does not emphasize memory deficits. To meet ADDTC criteria for probable vascular dementia, there must be a clear temporal relationship between the cerebral event and the onset of dementia if only one stroke has occurred, but this is not necessary if there is evidence of two or more strokes. The ADDTC criteria for possible vascular dementia include cases with a single stroke and no clear temporal relationship between the stroke and the onset of dementia, as well as individuals with clinical and neuroimaging evidence for Binswanger’s disease.

The NINDS-AIREN definition of dementia requires impairment of memory and at least two other cognitive domains. The NINDS-AIREN criteria for probable vascular dementia require clinical and radiological evidence of cerebrovascular disease as well as a clear temporal relationship between dementia onset and stroke, which is arbitrarily set at a maximum of 3 months. However, abrupt deterioration or a stepwise course without a temporal relationship are also included in the probable vascular dementia criteria. The NINDS-AIREN criteria for possible vascular dementia include cases with no neuroimaging, no clear temporal relationship, and an atypical course.

The ICD-10 and DSM-IV criteria require the presence of significant cerebrovascular disease that reasonably may be judged to be etiologically related to the dementia. The decline in cognitive abilities must include memory impairment and deterioration in judgment and thinking such as planning and organizing. In addition, emotional changes are required and clearly outlined, and, contrary to other sets of criteria, focal neurological findings are restricted to unilateral spastic weakness of the limbs, unilaterally increased tendon reflexes, an extensor plantar response, or pseudobulbar palsy. An unequal distribution of impaired cognitive functions is also required.

The DSM-IV criteria include focal neurological signs and symptoms or laboratory evidence of cerebrovascular disease. They also require multiple cognitive deficits manifested by both impaired memory and at least one of apraxia, agnosia, aphasia, or disturbance in executive functions. Deficits must represent a decline from a previous level, must lead to substantial impairment in social or occupational functioning, and must not occur exclusively during the course of a delirium.

Patients were classified as having either nonvascular dementia, possible vascular dementia, or probable vascular dementia according to the ADDTC and the NINDS-AIREN criteria. Patients who met the conditions for probable vascular dementia were also considered to meet conditions for possible vascular dementia. Patients were classified as having nonvascular or vascular dementia according to the DSM-IV and ICD-10 criteria.

Sensitivities and specificities were calculated for each of the resulting clinical classifications by using the neuropathological diagnosis as the gold standard. Chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests were used to assess possible associations between categorical variables. The kappa statistic was used to measure agreement among the sets of criteria. Results of continuous variables are expressed as means and standard deviations.

Results

The autopsy series consisted of 55 women and 34 men. Neuropathologically there were 20 cases of vascular dementia (mean age=83.6 years, SD=7.0; 13 women and seven men), 46 cases of Alzheimer’s disease (mean age=84.1 years, SD=6.6; 30 women and 16 men), and 23 cases of mixed dementia (mean age=86.7 years, SD=5.6; 12 women and 11 men).

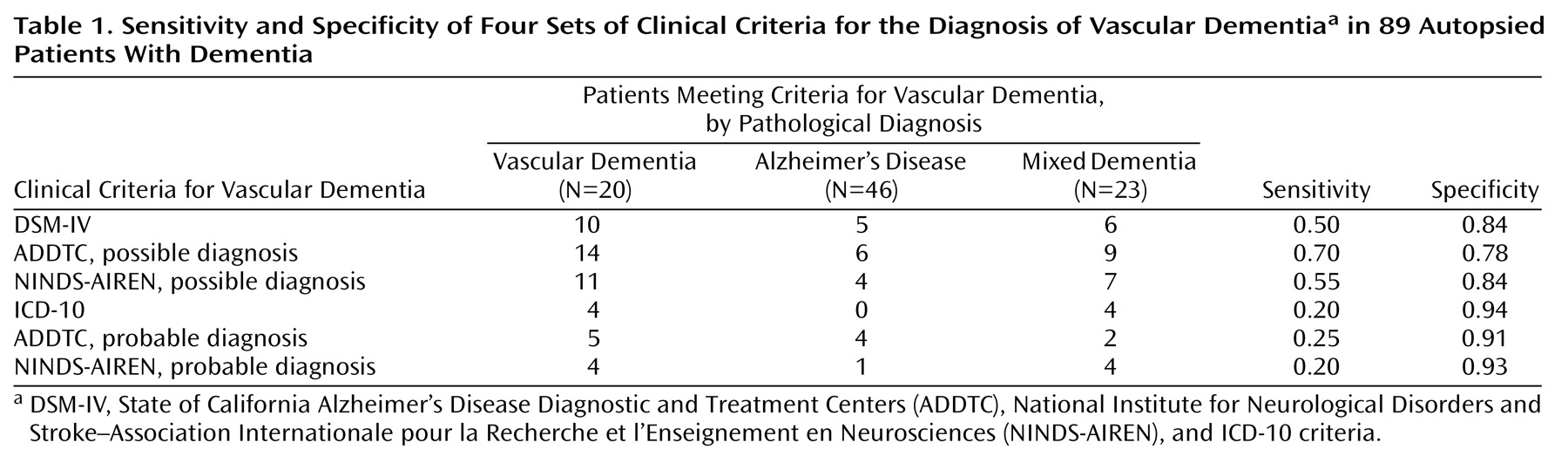

The ADDTC criteria for possible vascular dementia were the most sensitive, followed by the NINDS-AIREN criteria for possible vascular dementia and the DSM-IV criteria for vascular dementia. The ICD-10 criteria for vascular dementia as well as the ADDTC and NINDS-AIREN criteria for probable vascular dementia had very low sensitivities for the detection of vascular dementia. Conversely, the three latter criteria sets were the most specific (

Table 1). More importantly, there was a significant association between the neuropathological diagnosis (vascular or nonvascular dementia) and the DSM-IV criteria for vascular dementia (χ

2=9.9, df=1, p=0.002) as well as the ADDTC (χ

2=16.4, df=1, p<0.001) and NINDS-AIREN (χ

2=12.7, df=1, p<0.001) criteria for possible vascular dementia. In contrast, the associations between the neuropathological diagnosis and the ICD-10 criteria for vascular dementia (p=0.07, Fisher’s exact test) and the ADDTC (p=0.12, Fisher’s exact test) and NINDS-AIREN (p=0.11, Fisher’s exact test) criteria for probable vascular dementia were not statistically significant.

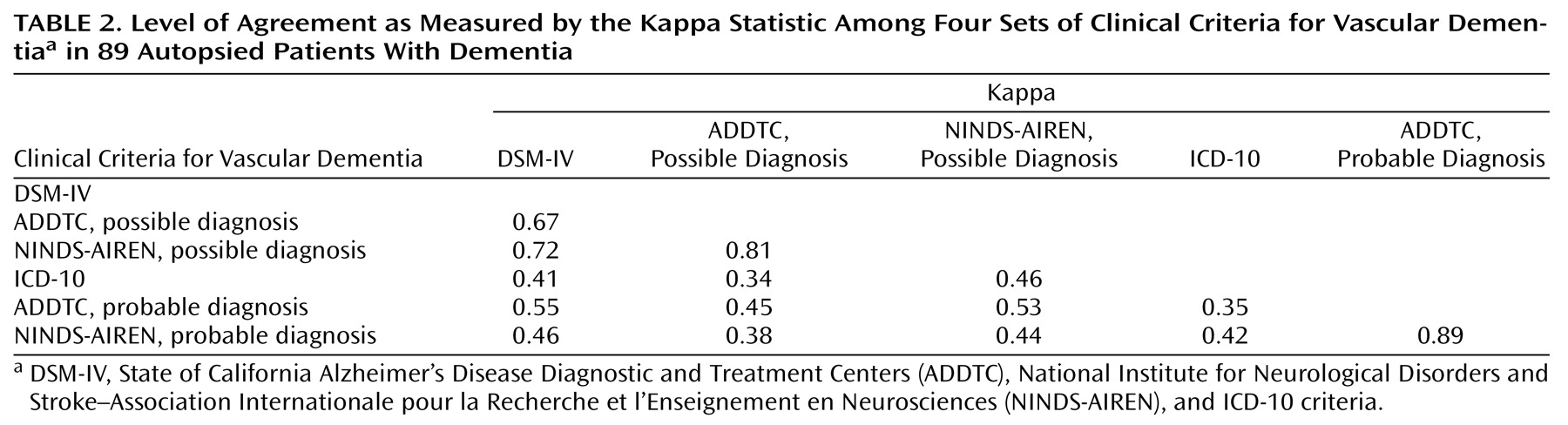

Agreement among the three most sensitive criteria sets was substantial according to the kappa statistic, which ranged from 0.67 to 0.81. However, there was very little agreement between the ICD-10 criteria for vascular dementia and either the ADDTC or the NINDS-AIREN criteria for probable vascular dementia (

Table 2). Thus, although the latter three sets of criteria perform similarly with regard to sensitivity and specificity, they do not select identical patients.

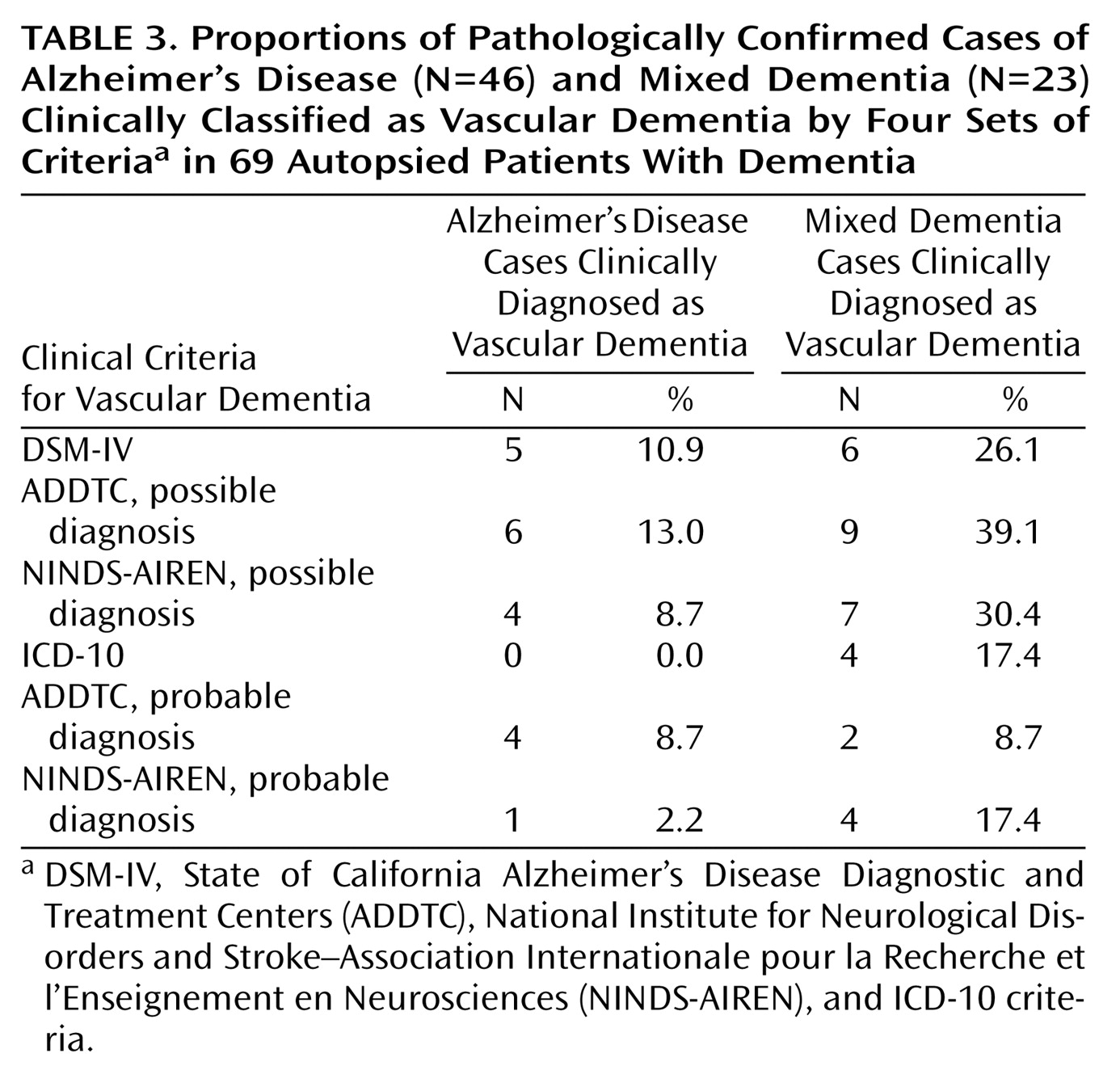

Only a few patients with Alzheimer’s disease were misclassified as having vascular dementia by any of the criteria sets: the range of misclassification was 0% of those diagnosed by ICD-10 and 13% of those diagnosed by ADDTC criteria for possible vascular dementia. However, the proportion of cases of mixed dementia identified as vascular dementia varied significantly, from 9% of those diagnosed by ADDTC criteria for probable vascular dementia to 39% of those diagnosed by ADDTC criteria for possible vascular dementia (

Table 3). Thus, although all of the criteria can distinguish Alzheimer’s disease from vascular dementia relatively well, they perform very differently with regard to mixed dementia.

Among the 20 cases with neuropathologically confirmed vascular dementia, focal neurological deficits were absent in most cases that were not recognized as vascular dementia by the NINDS-AIREN criteria for probable vascular dementia (N=10 of 16, 63%), the ADDTC criteria for probable vascular dementia (N=10 of 15, 67%), the DSM-IV criteria for vascular dementia (N=9 of 10, 90%), and the ICD-10 (N=12 of 16, 75%) for vascular dementia. In this latter group, the ICD-10 criterion for an unequal distribution of cognitive deficits was not met in 15 (94%) of the 16 cases. A clear temporal relationship between the onset of dementia and a cerebrovascular event was absent in all cases that were misclassified as nonvascular dementia by the ADDTC or the NINDS-AIREN probable criteria.

Boolean combinations of the four sets of criteria or of individual items selected among these sets did not lead to substantial gains in sensitivity or specificity. For example, combining two criteria from DSM-IV pertaining to the definition of dementia and one criterion for possible vascular dementia from the ADDTC (history or evidence of a single stroke without a clear temporal relationship with dementia onset) led to a sensitivity of 0.63 and a specificity of 0.85. Positive and negative predictive values, which are prevalence dependent, were very similar for all sets of criteria. Positive predictive value ranged from 0.44 (NINDS-AIREN probable) to 0.50 (NINDS-AIREN possible), and negative predictive values from 0.80 (ICD-10) to 0.90 (ADDTC possible).

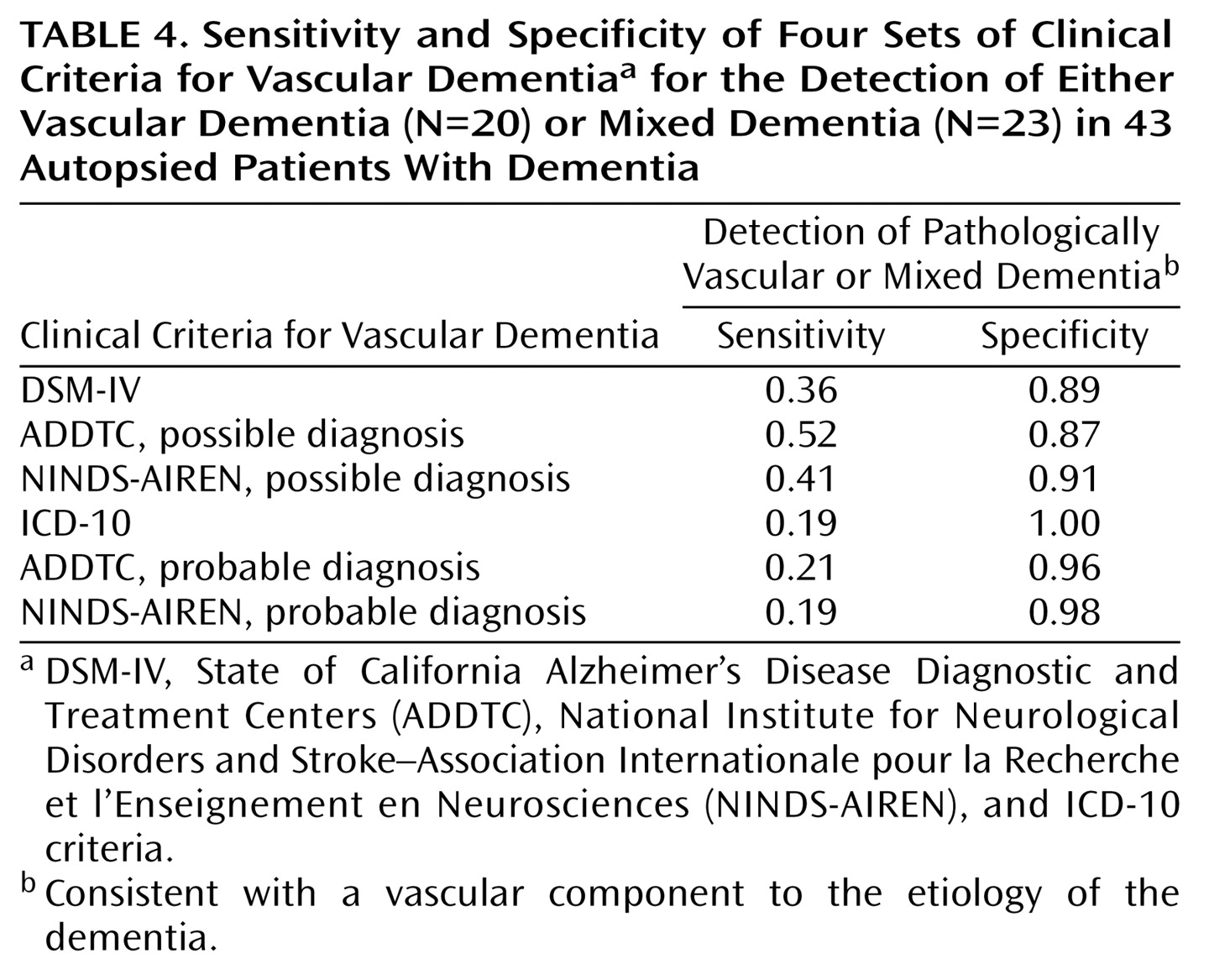

We also explored the ability of the four sets of criteria to differentiate patients with Alzheimer’s disease from patients with either mixed dementia or vascular dementia—that is, patients with a pure degenerative dementia from patients with a vascular component to the etiology of their cognitive impairment. Sensitivity for the detection of these cases was remarkably low, ranging from 0.19 with the ICD-10 criteria for vascular dementia and the NINDS-AIREN criteria for probable vascular dementia to 0.52 with the ADDTC criteria for possible vascular dementia (

Table 4).

Discussion

The strengths of this study include the relatively large size of the series of neuropathologically confirmed cases of dementia, the presence of a head CT or MRI in all cases, and the fact that all charts were reviewed by the same physician and all autopsies were performed by the same neuropathologist, each blind to the other’s findings. However, two limitations should be taken into account in the interpretation of our data. First, as usual in an autopsy series, the present hospital-based cohort cannot be considered representative of the whole spectrum of patients with vascular dementia. Second, in the absence of widely accepted neuropathological criteria for vascular dementia and to ensure a study group with pure vascular dementia, we applied a restrictive definition of cases based on the presence of both microscopic and macroscopic cortical infarcts that affected at least three neocortical association areas exclusive of the secondary visual cortex. In this respect, our data address the validity of diagnostic criteria for the detection of multi-infarct dementia but not for other forms of vascular dementia such as lacunae, white matter changes secondary to small vessel disease, hypoperfusion, and hemorrhage.

To our knowledge, the present data demonstrate for the first time that DSM-IV criteria perform much better than ICD-10 criteria in identifying cases of vascular dementia. In fact, although there was a trend toward an association between the neuropathological classification and ICD-10 criteria, this did not reach statistical significance. However, it is important to note that the ICD-10 research criteria for vascular dementia evaluated in our study differ from ICD-10’s general clinical descriptions and diagnostic guidelines

(20). The research criteria have unusually precise requirements. In a recent clinical study of 107 patients with poststroke dementia

(7), the number of cases that could be identified as vascular dementia according to ADDTC and DSM-IV criteria was more than double the number of cases identified by ICD-10. Another clinical study of 72 patients with dementia that used ICD-10 revealed that only 25% of patients fulfilling criteria for dementia and showing vascular lesions on CT scan met the criteria for vascular dementia

(20). Our study, which includes neuropathological data, confirms these findings and expands on them by showing that 80% of cases of vascular dementia are undetected by ICD-10.

Very low sensitivity is also the main handicap of the ADDTC and NINDS-AIREN criteria for probable vascular dementia. Furthermore, we could not demonstrate a significant association between these criteria sets and the presence or absence of neuropathologically confirmed vascular dementia. The need for a clear temporal relationship between dementia and stroke is a main limiting factor leading to this unexpectedly high percentage of false negative cases. If prospective studies confirm this finding, this particular component of these criteria may need to be revised.

Compared with the ADDTC and NINDS-AIREN criteria for probable vascular dementia, the DSM-IV criteria for vascular dementia and the NINDS-AIREN criteria for possible vascular dementia are associated with a substantial gain of sensitivity and a moderate loss of specificity. The exclusion of almost half of the pathologically confirmed cases of vascular dementia appears to be related in both sets of criteria to the frequent absence of focal neurological signs. It is of note that these criteria were not able to identify many of the cases with either vascular dementia or mixed dementia, suggesting that their relatively low sensitivity reflects their fair ability to detect the vascular component of dementing conditions.

Consistent with our previous data

(13) the ADDTC criteria for possible vascular dementia proved to be the most sensitive. Identification of cases according to these criteria is based on history or evidence of a single stroke even without a clear temporal relationship with onset of dementia. Despite this broad definition, our results show only a small loss of specificity compared with the other sets of criteria. The DSM-IV criteria for vascular dementia and the ADDTC and NINDS-AIREN criteria for possible vascular dementia performed similarly and relatively well in excluding Alzheimer’s disease, yet the ADDTC criteria for possible vascular dementia appear less effective in excluding mixed dementia.

All of the criteria studied show relatively low positive predictive values, indicating that their use in our particular group of autopsied patients misidentified almost 50% of the cases that met these clinical criteria. In this respect, it is important to note that the ADDTC criteria for possible vascular dementia successfully detected more than three times more cases of vascular dementia than the ICD-10 criteria even though they have similar positive predictive values. Moreover, ADDTC criteria for possible vascular dementia displayed the highest negative predictive value in our setting, suggesting that when not satisfied they could safely exclude vascular dementia.

Although sensitivity and specificity are indicative of the performance of the criteria studied for the diagnosis of vascular dementia in different populations, it should be kept in mind that the positive and negative predictive values reported here apply only to populations with an identical prevalence of dementia subtypes. In populations where the prevalence of vascular dementia is known, Bayes theorem can be applied to determine the posttest probability of this type of dementia by using the sensitivity and specificity of each set of criteria.

We found a moderate to good level of agreement between the ADDTC and the NINDS-AIREN criteria as well as between the DSM-IV criteria for vascular dementia and the ADDTC and NINDS-AIREN criteria for possible vascular dementia; however, agreement among the other sets of criteria was poor. Our results are in keeping with several previous studies showing that current diagnostic criteria for vascular dementia identify different clusters of patients

(7,

9,

13,

21,

22) and confirm that currently available criteria for vascular dementia are not interchangeable. In this light, clinicopathological validation studies can provide key information for researchers and clinicians who must chose among them.

In conclusion, our results reveal substantial differences among the criteria studied. The ADDTC criteria for possible vascular dementia achieved the best balance between an acceptable level of sensitivity and relatively high specificity and may represent the best alternative for use in clinical settings. However, if exclusion of mixed dementia cases is important, DSM-IV might be preferred despite its lower sensitivity. ICD-10 criteria for vascular dementia as well as the ADDTC and NINDS-AIREN criteria for probable vascular dementia suffered from extremely low sensitivities and did not relate significantly to neuropathological findings. The relatively poor and unequal performance of current clinical criteria for vascular dementia stresses the need for improved diagnostic methodology and the development of an international consensus.