Smokers with a history of major depression are known to experience great difficulty when they attempt to stop smoking. They often have lower cessation rates and, when they are able to stop smoking, experience more severe withdrawal symptoms and higher incidences of depressed mood and of new episodes of major depression during the postcessation period than do smokers who do not have a history of major depression

(1). Prompted by that knowledge, we conducted a randomized, placebo-controlled trial to test the efficacy of sertraline as a cessation aid for smokers with a history of major depression. Sertraline is a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) with proven efficacy for alleviating depressive disorders

(2). This hypothesis is in line with observations from two independent trials of fluoxetine

(3,

4), also an SSRI, that showed an apparent benefit of the drug among smokers who manifested at least subclinical levels of depression before cessation, although not among smokers without depressed mood at baseline.

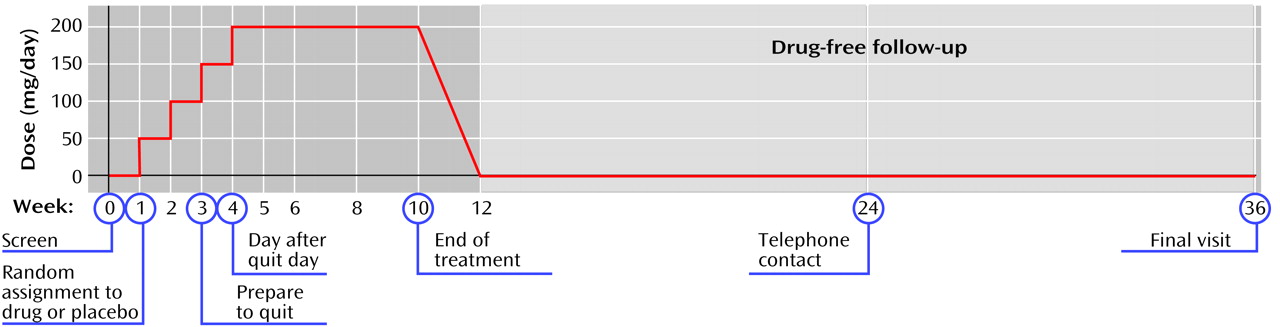

The prospective nature of the study design also permitted an investigation of sertraline’s effect on the intensity of withdrawal symptoms. It was expected that sertraline use would be associated with less discomfort during the first week after the quit day.

Method

Subjects

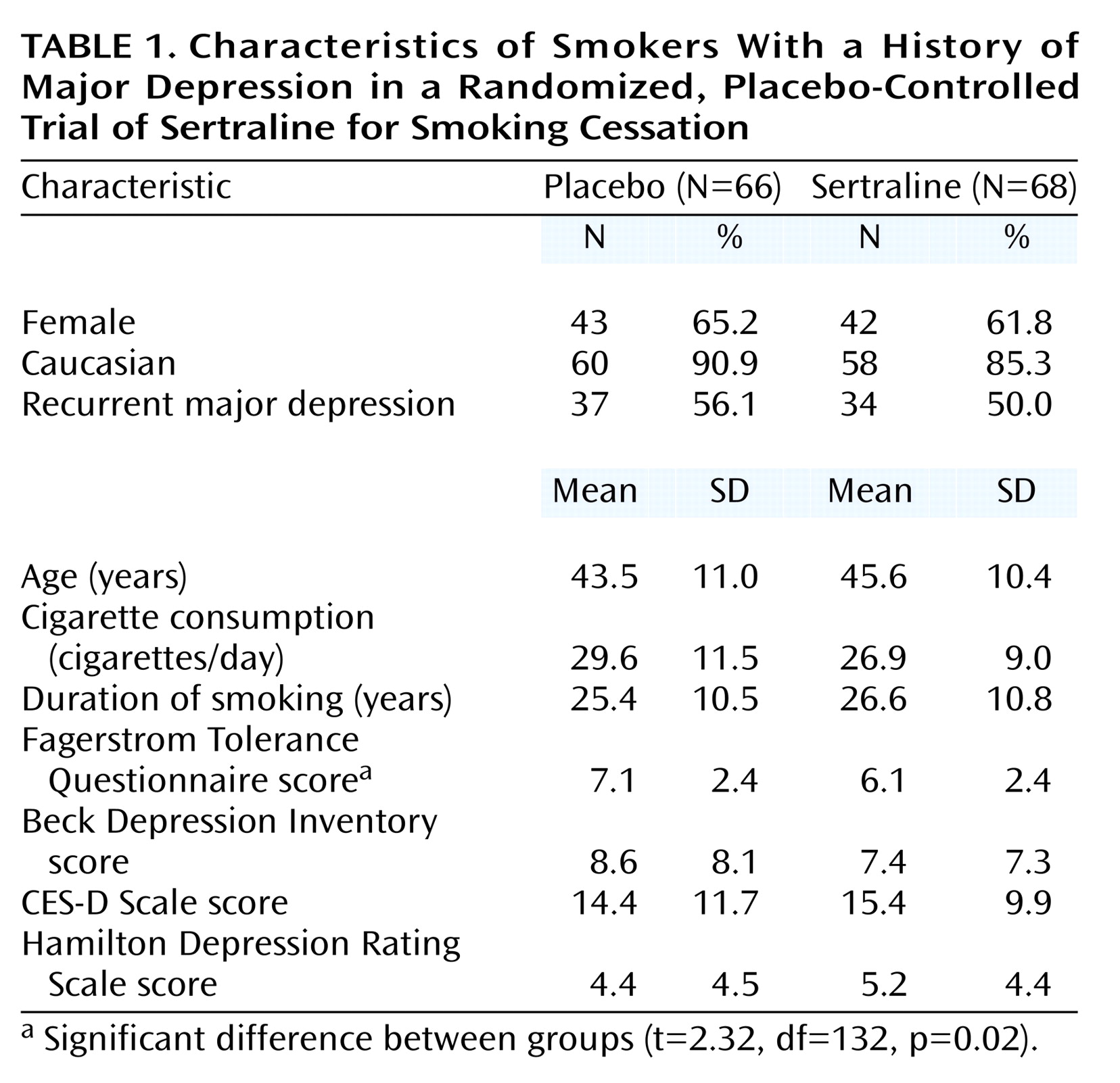

Subjects were required to meet the DSM-III-R criteria for at least one episode of major depression, which must have remitted more than 6 months before the start of the study. Additional entry criteria were age between 18 and 70 years, daily use of 20 or more cigarettes for at least 1 year, and at least one prior attempt to stop smoking. The exclusion criteria were serious medical illness; use of a psychotropic medication, major depression, alcohol or drug dependence, panic disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, anorexia nervosa, or bulimia nervosa within the past 6 months; lifetime diagnosis of bipolar disorder, antisocial or schizotypal personality disorder, severe borderline personality disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, or psychosis including schizophrenia; and pregnancy or lactation.

This study was approved by the institutional review board of the New York State Psychiatric Institute. Participants were recruited through newspaper and other print advertisements in the New York metropolitan area. To avoid false reporting of a history of major depression by volunteers in order to qualify for the study, these advertisements did not mention that a history of major depression was an entry criterion. The respondents were first screened by telephone, and those who met the initial criteria with respect to smoking and past major depression were seen at an initial clinic visit. The study procedures were fully explained by the study physician (K.S.) to each prospective participant, who then indicated informed consent by signing the informed consent form approved by the institutional review board for this particular study. A medical and psychiatric history, physical examination, electrocardiogram, and blood chemistry screen were then performed to ensure that the participant fulfilled all entry criteria. Participants were seen from October 1993 to January 1997.

Study Protocol

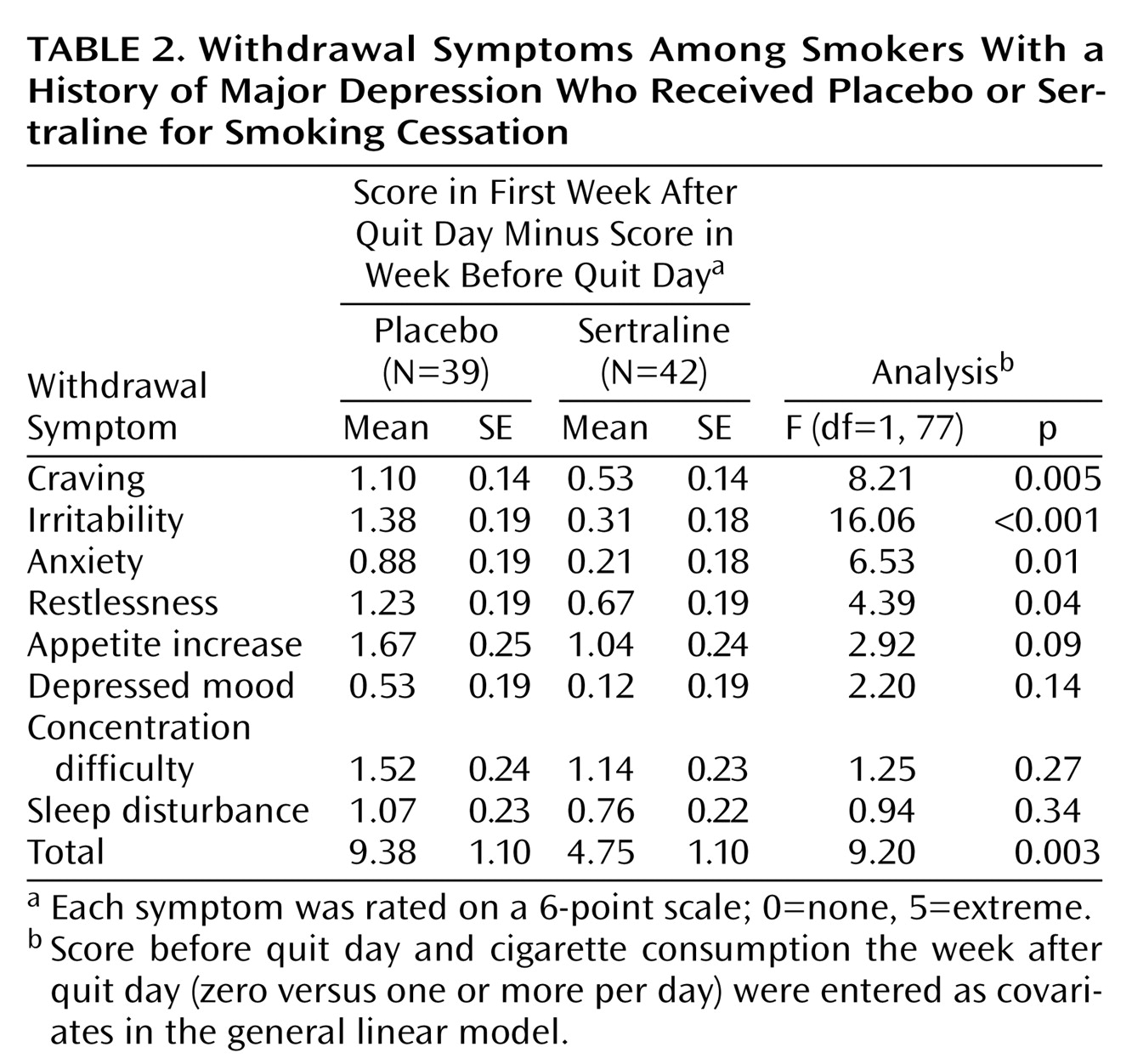

The schedule of study procedures is shown in

Figure 1. Participants who were considered eligible on the basis of the information obtained at the screening visit began a 1-week single-blind washout phase of one placebo tablet per day. After 1 week, subjects whose medical eligibility was confirmed by the laboratory tests were randomly assigned in double-blind fashion to receive sertraline (in 50-mg tablets) or matching placebo pills. Medications were provided in prepared bottles that were numbered according to the randomization schedule and dispensed at each visit. All study staff at the clinic site were blinded to treatment assignment. Compliance with the medication schedule was assessed by pill counts at each visit.

At the visit when random assignment took place (week 1), the subjects were instructed to continue taking a single morning dose of the medication (placebo or 50 mg of sertraline) during the following week and to increase their study medication by 1 tablet each week for the next 2 weeks; that is, patients in the sertraline group received 100 mg/day through week 2 and 150 mg/day through week 3. At week 3, each subject was asked to select a target quit day that would fall approximately 7 days later. The subjects were encouraged to reduce the number of cigarettes they smoked as they approached the quit day and instructed to stop smoking completely as of that quit day. Until week 3, the subjects had been asked to maintain their pretreatment level of smoking.

Each subject returned for a clinic visit on the day following the quit day. On the assumption that a subject’s failure to reduce smoking to 50% of his or her baseline level indicated a lack of the motivation level required to stop smoking, subjects who did not meet this cutoff were removed from the study. The subjects who remained were then instructed to increase their medication dose to 4 tablets (200 mg/day of sertraline) and to continue this dose for the next 6 weeks. At the end of that period, the subjects tapered the study medication by 1 tablet (50 mg of sertraline) every 3 days and returned for a posttreatment clinic visit in 2 weeks. In sum, the subjects were required to take the study medication for 11.3 weeks: 1 week of placebo washout, 3 weeks for medication buildup before the quit day, 6 weeks at full dose (200 mg/day of sertraline), and a 9-day taper period. All subjects entered a 6-month follow-up phase; they were contacted by telephone 3 months after the end of treatment and asked to return to the clinic at 6 months.

Counseling

The participants were seen at each of the nine clinic visits by an experienced therapist (L.S.C. or F.S.) and monitored for adverse reactions by a study psychiatrist (K.S. or A.H.G.). The counseling protocol, described in detail elsewhere

(7), incorporated standard smoking cessation techniques (i.e., orientation to the health risks of smoking and benefits of cessation, skills training for coping with withdrawal symptoms and avoiding relapse) and was augmented by a supportive approach designed to help the smoker recognize, express, and manage negative affects related to the effort to quit. We took this extra step in the counseling process in an attempt to reduce withdrawal symptoms, since these have been reported to be more severe and predictive of cessation failure among smokers with a history of major depression

(8–

10). The counseling sessions typically lasted 45 minutes.

Measures

The main study outcome was point-prevalence rate of abstinence during the preceding 7 days, ascertained by self-report at each clinic visit (and by telephone at month 3 during the follow-up phase). These reports were biologically verified (by a serum cotinine level less than 25 ng/ml) at the end of treatment and at the visit at the end of the 6-month follow-up. The subjects lost to follow-up after random assignment were considered treatment failures. To assess current major depression (an exclusion criterion) or past history of major depression (an entry requirement), the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R

(11) was administered. Interrater tests conducted with 10 subjects to monitor the reliability of the diagnostic assessments indicated substantial agreement between the raters (L.S.C. and F.S.). Nicotine dependence level was measured by the Fagerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire

(12). Depressed mood at baseline was measured by using the Beck Depression Inventory

(13), the Center for Epidemiology Depression Scale (CES-D Scale)

(14), and the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale

(15). Withdrawal symptoms (craving, irritability, anxiety, restlessness, concentration difficulty, depressed mood, appetite increase, and sleep disturbance) were rated at each clinic visit by using a 6-point rating scale (0=none, 5=extreme).

Statistical Analysis

Given the number of subjects, we had 85% power to detect a statistically significant (alpha=0.05, two-tailed test) difference between drug and placebo with estimated end-of-treatment abstinence rates of 15% for placebo and 40% for sertraline. The estimate for placebo is based on that observed among placebo-treated smokers with past major depression seen in an earlier study by our group

(16); the estimate for sertraline is a conservative estimate based on the 50% end-of-treatment abstinence rate among smokers with past major depression who were treated with the experimental drug (clonidine) in the previous study

(16).

Chi-square tests and t tests were used to assess the significance of differences between the placebo- and sertraline-treated subjects. The general linear model procedure in SPSS 10.0 for Windows (Chicago, SPSS) was used to test the effects of sertraline, relative to those of placebo, on change in symptom ratings between the week before the quit day and the end of the first week after the quit day. Statistical significance was set at p<0.05 (two-tailed tests).

Discussion

Studies of addiction treatment have increasingly demonstrated that the associated withdrawal symptoms are manageable with appropriate medication

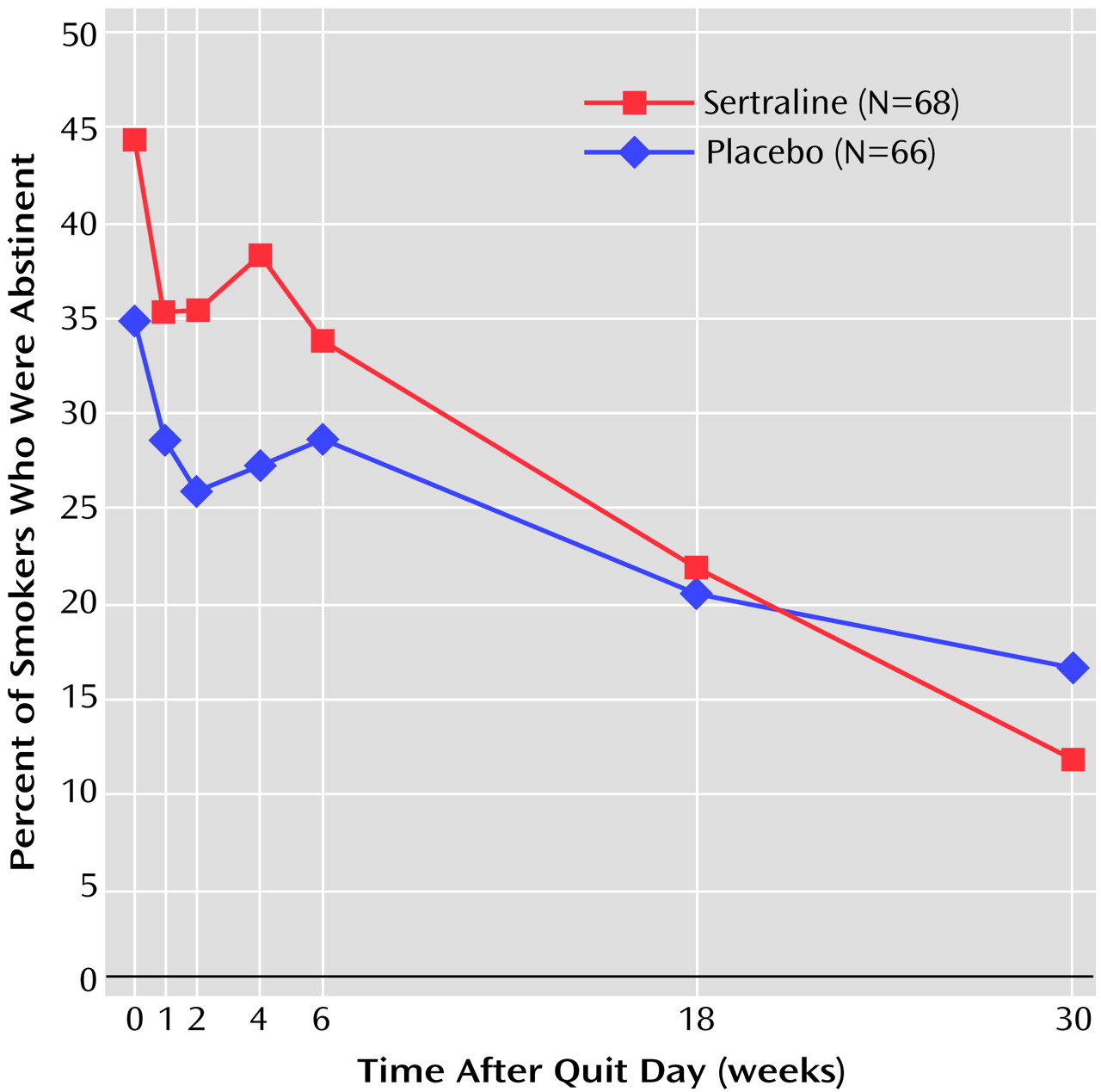

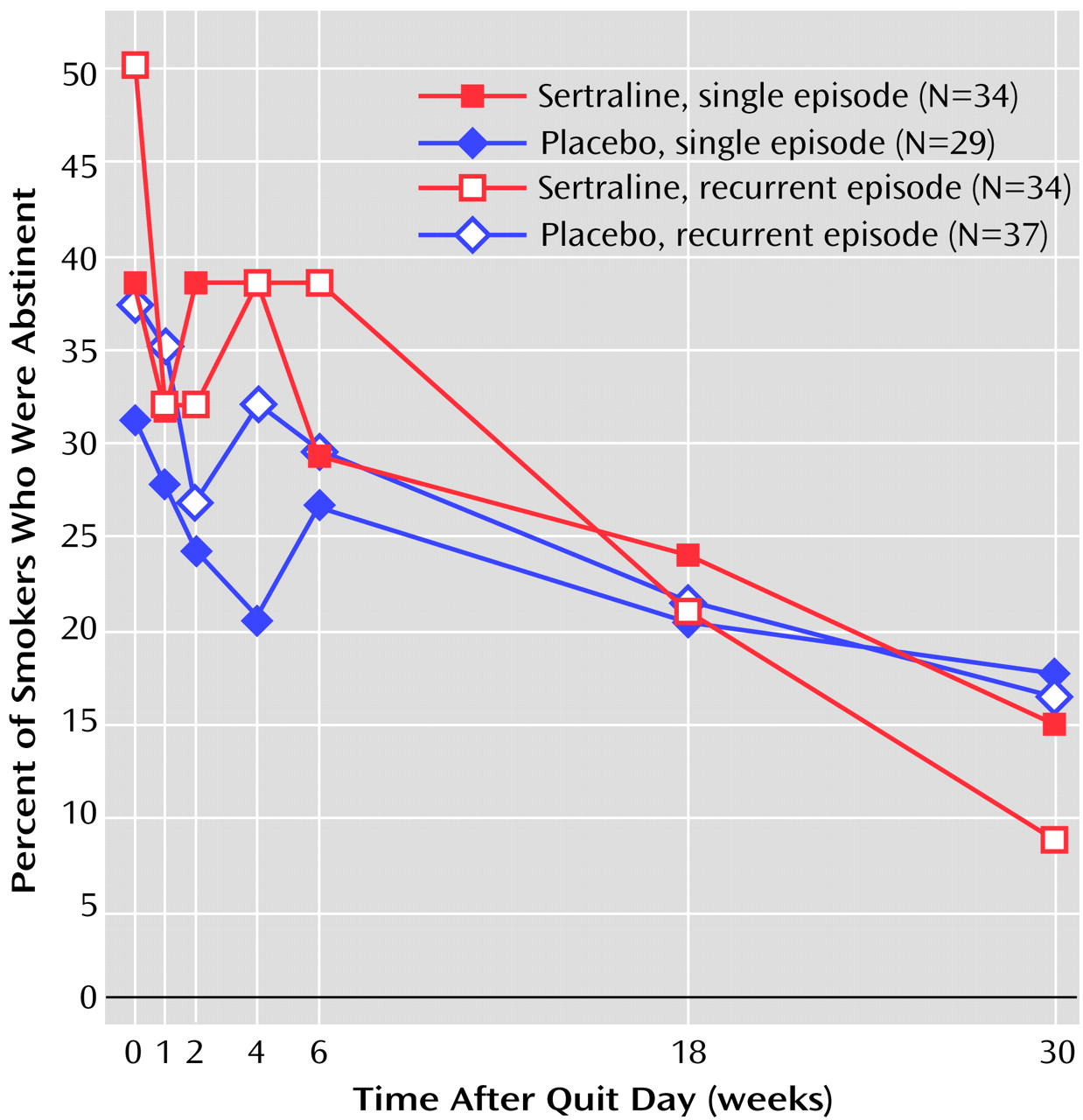

(17). Our finding that sertraline reduces the intensity of withdrawal symptoms is consistent with that belief. Unfortunately, that salutary effect of sertraline did not extend to cessation itself in the present study. Despite slightly higher abstinence rates for sertraline during the first several weeks after the quit day (

Figure 3), these rates converged to 33.8% for sertraline and 28.8% for placebo by the end of the active treatment period.

The absence of a treatment effect persisted during the 6-month drug-free follow-up phase. Further data analysis did not indicate a difference in trend by single-episode versus recurrent subtype of major depression (

Figure 3) or by other putative predictors of abstinence (Fagerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire score, number of cigarettes per day, depressed mood, gender). Because these negative results contradict our empirically based hypotheses regarding the usefulness of antidepressant medication for smokers with a history of depression and also do not correspond with published findings on fluoxetine for smokers with depressed mood

(3,

4), we will discuss possible reasons for our finding on sertraline and cessation outcome and factors that challenge the validity of that finding.

Sertraline is only one of several antidepressant medications that have been tested as treatments for tobacco dependence. This line of research was founded on observations regarding the deleterious influence of depressed mood

(18,

19) and major depressive disorder

(16) on cessation. Of the antidepressants that have been tested, only bupropion

(20,

21) and nortriptyline

(22) have convincingly demonstrated efficacy for smoking cessation. Furthermore, contrary to expectations, bupropion and placebo did not exert differential effects on depressed mood during the withdrawal period

(20), and the positive effect of nortriptyline was observed irrespective of a history of depression

(22). Fluoxetine, on the other hand, yielded largely negative results in a large-scale multisite trial of smokers (J.S. Mizes et al., unpublished study, 1996). Nevertheless, supporting our initial expectations, two reports from placebo-controlled trials of fluoxetine

(3,

4) contained data suggesting some advantage of the drug among smokers with elevated scores on scales measuring depressed mood. The first of these studies

(4) used subjects from selected sites in the multisite fluoxetine study reported by Mizes and colleagues and examined the likelihood of abstinence as a function of baseline score on the Hamilton depression scale. While no main effect of fluoxetine was observed in the intent-to-treat analysis, further examination among subjects who were compliant with the treatment protocol indicated increasing efficacy of fluoxetine relative to placebo with increasing scores on the Hamilton depression scale

(3). Similarly, in 12-month data from a placebo-controlled trial of fluoxetine plus a nicotine inhaler, Blondal and colleagues

(3) also found no evidence that fluoxetine improved abstinence among unselected smokers; however, among high scorers on the Beck Depression Inventory, the researchers found a higher abstinence rate in the fluoxetine group than in the placebo group. Trials of the tricyclic antidepressant doxepin

(23) and of moclobemide, a monoamine oxidase inhibitor

(24), have also been conducted, but these produced weak effects and as yet do not have the benefit of replication.

Characteristics of study design may partly account for some of the inconsistencies among study findings, but additional reasons may lie in the interface of antidepressant compounds and the complex neurobiology of tobacco dependence. For instance, bupropion and nortriptyline, which produced positive results, are known to affect dopaminergic and adrenergic neurons, while fluoxetine and sertraline affect primarily the serotonergic system. That negative results with respect to cessation have been observed with fluoxetine and now sertraline raises questions regarding the importance of serotonin in tobacco or nicotine dependence.

Conversely, we considered reasons that may have falsely led to the absence of a sertraline-placebo difference. Had we overdiagnosed the presence of a history of major depression? Were the cessation rates for placebo so similar to those for sertraline because of a placebo effect? Or were the cessation rates for the active drug so similar to placebo because of a ceiling effect?

With respect to the problem of diagnostic error, we are inclined to regard this as a small threat, having taken pains to prevent its occurrence from the outset. The diagnostic assessments were performed by experienced psychiatric interviewers (L.S.C. and F.S.); in cases of uncertainty, the subject was reinterviewed by the study psychiatrist (A.H.G. or K.S.), and a diagnosis of major depression was made only when consensus among the raters was obtained. In further support of the diagnostic composition of the study group, we note that, as reported in an earlier article

(25), we observed a 31% incidence of new major depressive episodes during the follow-up period among the abstinent smokers in the present group. This incidence of postcessation depression is much higher than would be expected from smokers without a history of major depression and is congruent with findings by Tsoh et al.

(26) and by our group

(27) that substantial proportions of abstainers with a history of major depression are at risk of new episodes of major depression after an attempt to quit smoking.

The placebo effect is an improved response because subjects think they are receiving the active medication. We do not have direct evidence relating to this issue since the impressions regarding treatment received were not systematically obtained from the subjects or from the counselors. Nevertheless, as discussed by Quitkin et al.

(28), the placebo effect is distinguishable from a true drug response in that it is short-lived, usually fading after 2 weeks. By contrast, the lack of placebo-sertraline differences in abstinence rates that began during the first week after the quit day continued through the 10 weeks of treatment and extended to the drug-free 6-month follow-up period. This evidence of persistence argues against a placebo effect.

The ceiling effect, as discussed by Paykel

(29) in comparisons of psychotherapy with medication treatment, occurs when no additional benefit from a second treatment is observed in the presence of an effective treatment. In the present study, because our counseling approach was intense in both content (a psychotherapeutic approach) and duration (45 minutes during nine clinic visits), we wondered whether it had comprised another active treatment and, even without the benefit of pharmacotherapy, resulted in a higher-than-expected cessation rate. Indeed, the cessation rates among the placebo-treated subjects in the present study group were higher than those we observed in two earlier studies in which the level of counseling support had been minimal and brief

(6,

16). In the first study

(16), the end-of-treatment success rate for placebo in smokers with past major depression was 13.6% (three of 22 subjects); in contrast, the end-of-treatment placebo rate in the present study was 28.8% (19 of 66). In the second study, where the recurrent and single forms of major depression were separated

(6), the end-of-treatment placebo success rate among subjects with recurrent major depression was 8.0% (two of 25), whereas the corresponding placebo success rate in the present study was, again, markedly higher, 29.7% (11 of 37). It is notable that others have observed the particular efficacy of psychological counseling for smokers with past major depression

(22) and alcohol disorder

(30). Also relevant is the finding by Brown and colleagues

(31) that cognitive behavior therapy for depression produced a cessation rate superior to that of a standard counseling protocol for smokers with a history of recurrent major depression. If a ceiling effect did occur, there are a number of implications. First, the study, as implemented, did not permit a valid comparison of sertraline with an appropriate inactive treatment; second, the efficacy of sertraline remains open to question; and third, since only a minority (about 30%) of the total study group succeeded in stopping smoking despite the high level of intervention they received, it is apparent that treatments other than those offered in our study were needed by this target group of smokers with a history of major depression. It is also noteworthy that the presumed advantage of the 9-week intensive psychological counseling did not persist beyond the treatment period, as only half of the end-of-treatment abstainers were still not smoking 6 months later.

The positive effect of sertraline on withdrawal symptoms despite the lack of benefit on cessation itself is intriguing. It contrasts with the evidence on nicotine replacement therapy

(32,

33) and bupropion

(34) that indicates positive effects of those agents on reduction of withdrawal symptoms as well as cessation. However, there are other medications that have also been observed to ameliorate withdrawal symptoms but were not found to improve cessation better than placebo. Examples are buspirone

(35) and paroxetine

(36). This finding implies that the intensity of withdrawal symptoms during the first week of treatment may not be a reliable surrogate in determining the promise of a new treatment. Hughes

(37) has suggested that duration of withdrawal symptoms may be a better predictor.

Contravening a promising theoretical rationale as well as prior observations with fluoxetine for smokers with depressed mood

(3,

4), this clinical trial did not provide encouraging evidence for sertraline as a cessation treatment for smokers with past major depression. However, the negative finding occurred in the context of a placebo cessation rate that was much higher than expected, raising the possibility that the intense level of concomitant psychological intervention received by all subjects prevented an adequate test of the active treatment. The additional finding that sertraline reduced withdrawal symptoms is noteworthy since this apparent advantage did not extend to cessation, a phenomenon observed as well for other, although not all, pharmacotherapies for tobacco dependence. These observations regarding sertraline and the ostensible value of intensive psychological counseling warrant consideration in future trials of candidate treatments for tobacco dependence.