The introduction of clozapine, risperidone, olanzapine, and quetiapine in the United States represents an important step forward in the treatment of schizophrenia. The “atypical” profile of these drugs has been linked to a combined antagonism of central serotonin type 2 (5-HT

2) and dopamine type 2 (D

2) receptors

(1,

2). In a meta-analysis

(3) we showed that these atypical antipsychotics are at least as effective as conventional drugs. Their main advantage is a lower risk of extrapyramidal side effects. Two of them also showed slight advantages in the treatment of negative symptoms. However, these drugs have been examined only for the treatment of acutely ill patients. It is therefore not clear whether the superiority relates to primary negative symptoms or merely to secondary negative symptoms. Studies with patients suffering predominantly from persistent negative symptoms would be more appropriate for assessing this issue

(4). Such studies have been undertaken with amisulpride—a substituted benzamide that has been used as an antipsychotic in France for more than 10 years

(5–

7). Although this antipsychotic does not block serotonin receptors at all, but is a high-affinity and highly selective D

3/D

2 receptor antagonist, it is said to have atypical properties as well

(8). It is believed that its selective affinity for dopamine receptors in the limbic structures, but not in the striatum, leads to a low risk of extrapyramidal side effects

(9,

10). Animal studies have shown that at low doses it preferentially blocks presynaptic dopamine autoreceptors; this blockage facilitates dopaminergic transmission and thus might make amisulpride effective for negative symptoms

(10). To further examine the different pharmacological models for atypicality, we performed a meta-analysis of the efficacy and safety of amisulpride. This was compared with an update of our previous meta-analysis of the 5-HT

2/D

2 antagonists.

Results

Study Characteristics

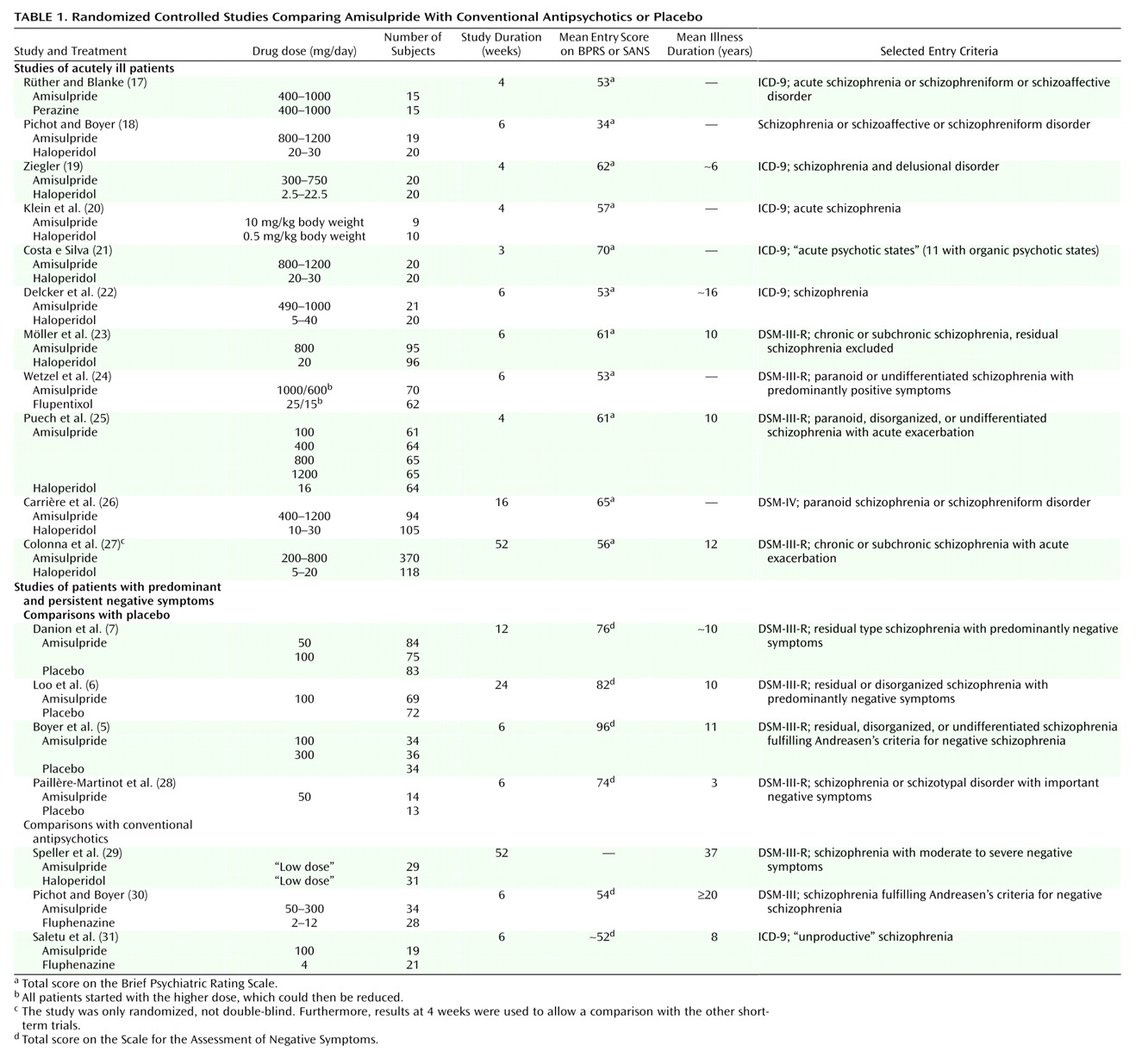

Eighteen randomized controlled trials including 2,214 patients were identified

(5–

7,

17–

31) (

Table 1); details of the studies on the 5-HT

2/D

2 antagonists have been published elsewhere

(3). Apart from the trial of Colonna et al.

(27), which was an open randomized study, all were double-blind and used a parallel design. Study durations ranged between 3 weeks and 1 year. There was some variation of diagnostic criteria over time; the earlier studies generally used ICD-9 and DSM-III, whereas the newest study

(26) used DSM-IV. Also, the newer studies used intent-to-treat, last-observation-carried-forward analyses, whereas some of the older investigations included only the study completers in their statistical analyses. As in our previous meta-analysis on the 5-HT

2/D

2 antagonists, the patients were typically in their mid-30s, the majority were male, they showed moderate to severe schizophrenic symptoms at baseline, and their mean duration of illness ranged between 3 and 37 years (median=10). The most common comparators were haloperidol and placebo, but four studies compared amisulpride with flupentixol

(24), perazine

(17), and fluphenazine

(30,

31). One randomized controlled trial

(32) had to be excluded, because it used risperidone and not a conventional antipsychotic as a comparator. Eleven trials examined the effectiveness of amisulpride for acutely ill patients, whereas seven studies examined low-dose amisulpride (50–300 mg/day) for patients with persistent, predominantly negative symptoms (with some variation of the criteria used). This symptom profile is different from that in the meta-analysis of the 5-HT

2/D

2 antagonists, for which only studies of patients with acute exacerbations of schizophrenia have been published, to our knowledge.

Update of Previous Meta-Analysis

Several new randomized controlled trials of the 5-HT

2/D

2 receptor antagonists have been published since our last meta-analysis

(3). Although these did not lead to significant changes of the overall results of our meta-analysis, they filled some important gaps in our knowledge about these compounds: Olanzapine was compared with chlorpromazine for treatment-resistant patients

(33) and with haloperidol for cannabis-induced psychoses

(34) and for a small group of male schizophrenic patients

(35). For quetiapine, results of a comparison with haloperidol have now been fully published

(36) but do not provide new data. For risperidone we identified two new comparisons with haloperidol or standard treatment for treatment-resistant patients

(37–

39). Emsley et al.

(40) compared risperidone and haloperidol in a study of antipsychotic-naive patients. One study

(41) compared risperidone with haloperidol for cannabis-induced psychosis, and a further study

(42) compared risperidone with methotrimeprazine and haloperidol. Two other studies compared risperidone with haloperidol and focused on cognitive functions

(43) or changes in plasma norepinephrine levels

(44). New studies with sertindole have not been published, to our knowledge, possibly because of the withdrawal of this drug from the market.

Several further studies on the 5-HT2/D2 receptor antagonists have been presented at congresses, but the abstracts did not allow extraction of the necessary data. It was also not possible to obtain these by contacting authors and pharmaceutical companies.

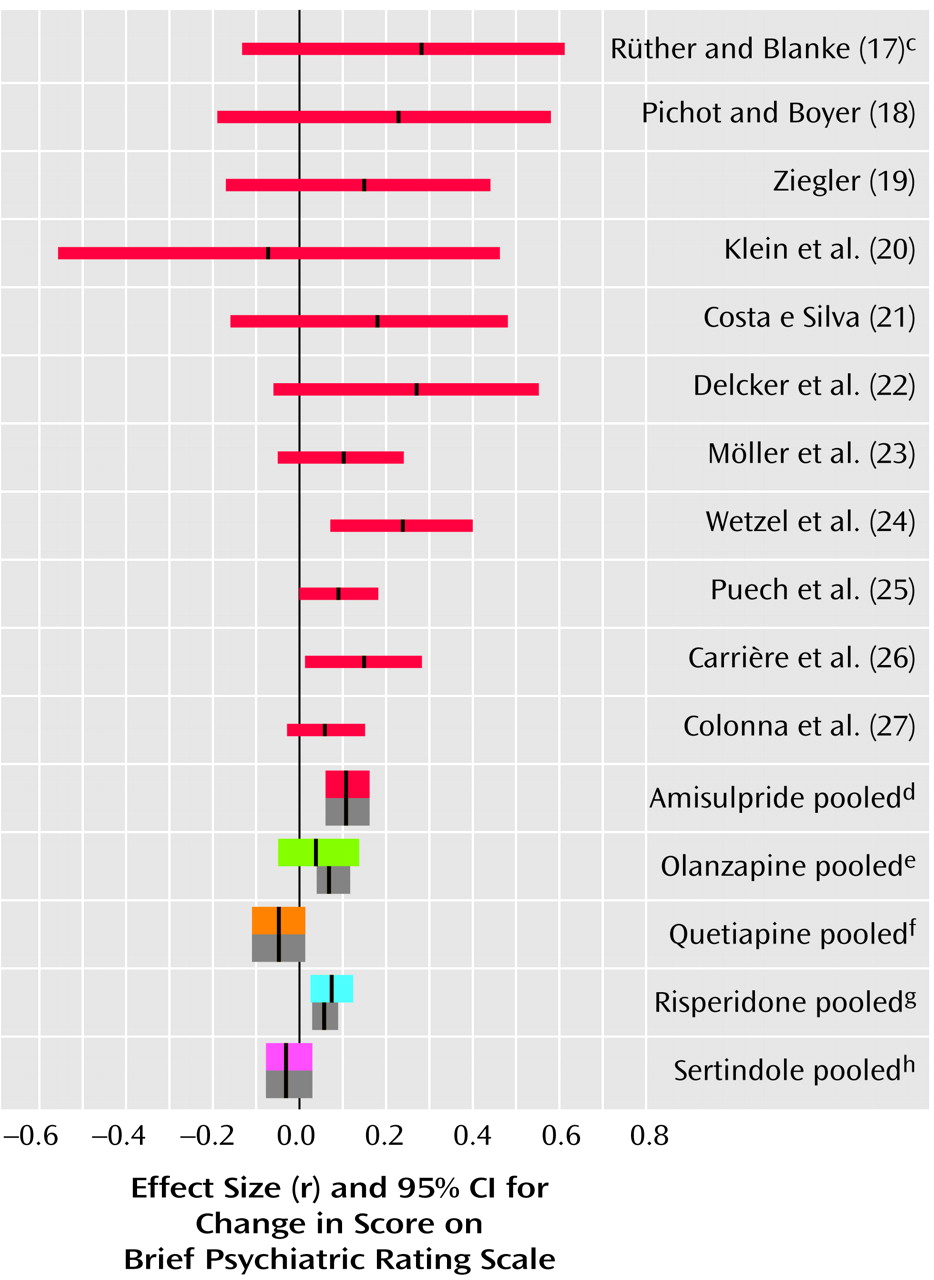

Reduction in BPRS Score

The patients suffering predominantly from negative symptoms showed hardly any positive symptoms and therefore were excluded from our analysis of change in BPRS score from baseline to endpoint. According to 10 studies with acutely ill patients, amisulpride was significantly superior to conventional antipsychotics. The mean effect size of r=0.11 indicates a superiority of amisulpride over conventional antipsychotics of roughly 11 percentage points. The result is remarkably consistent, since in all but one study there was at least a trend in favor of amisulpride (

Figure 1).

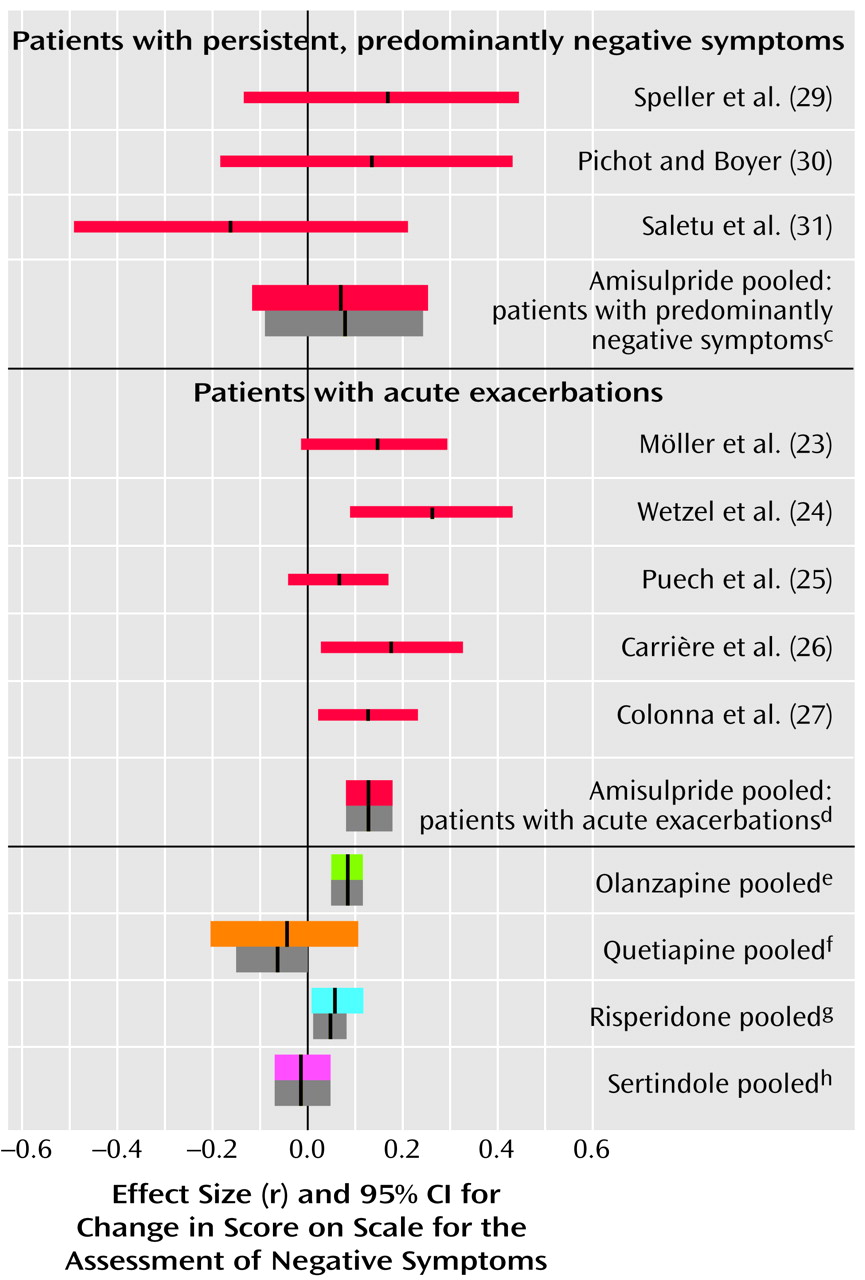

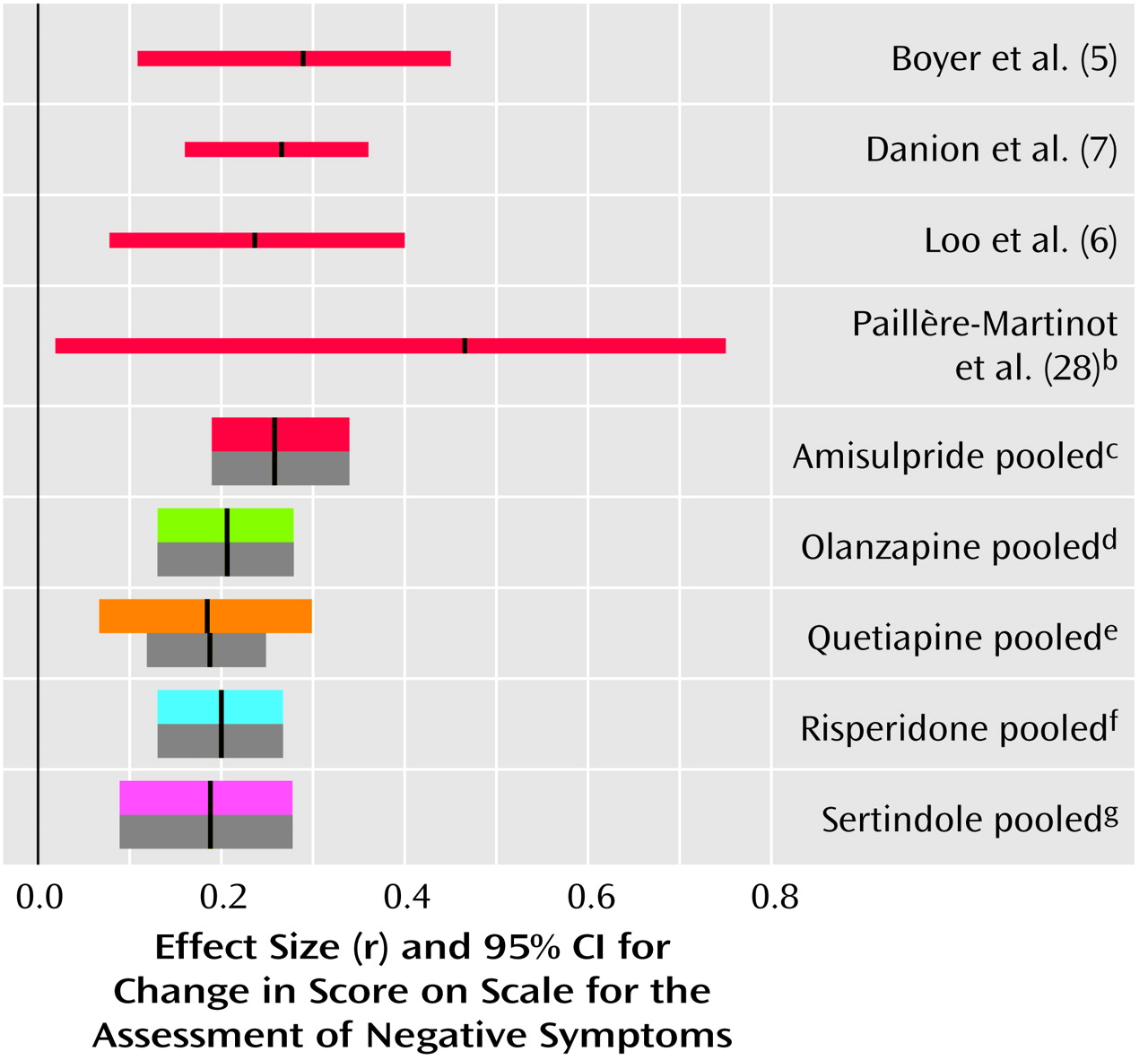

Negative Symptoms

In the studies of acutely ill patients, for negative symptoms there was again a clear and consistent superiority of amisulpride to conventional compounds (

Figure 2, middle). These studies do not, however, permit a conclusion as to whether the superiority affects primary negative symptoms or merely secondary negative symptoms (e.g., negative symptoms secondary to positive symptoms). Studies of patients suffering predominantly from persistent negative symptoms are more appropriate for this. As far as we know, such studies have been performed up to now only with amisulpride. In four studies with patients suffering predominantly from persistent negative symptoms amisulpride was significantly superior to placebo (

Figure 3). Olanzapine, quetiapine, risperidone, and sertindole were also significantly superior to placebo for negative symptoms (

Figure 3), but these results were derived only from studies with acutely ill patients. Only three small studies compared amisulpride with conventional antipsychotics for patients with predominantly negative symptoms. There was no significant difference between amisulpride and conventional drugs (

Figure 2, top). The high variability of the durations of the amisulpride studies on negative symptoms, ranging from 6 weeks to 12 months

(29), is notable, although no statistical heterogeneity of their results was found.

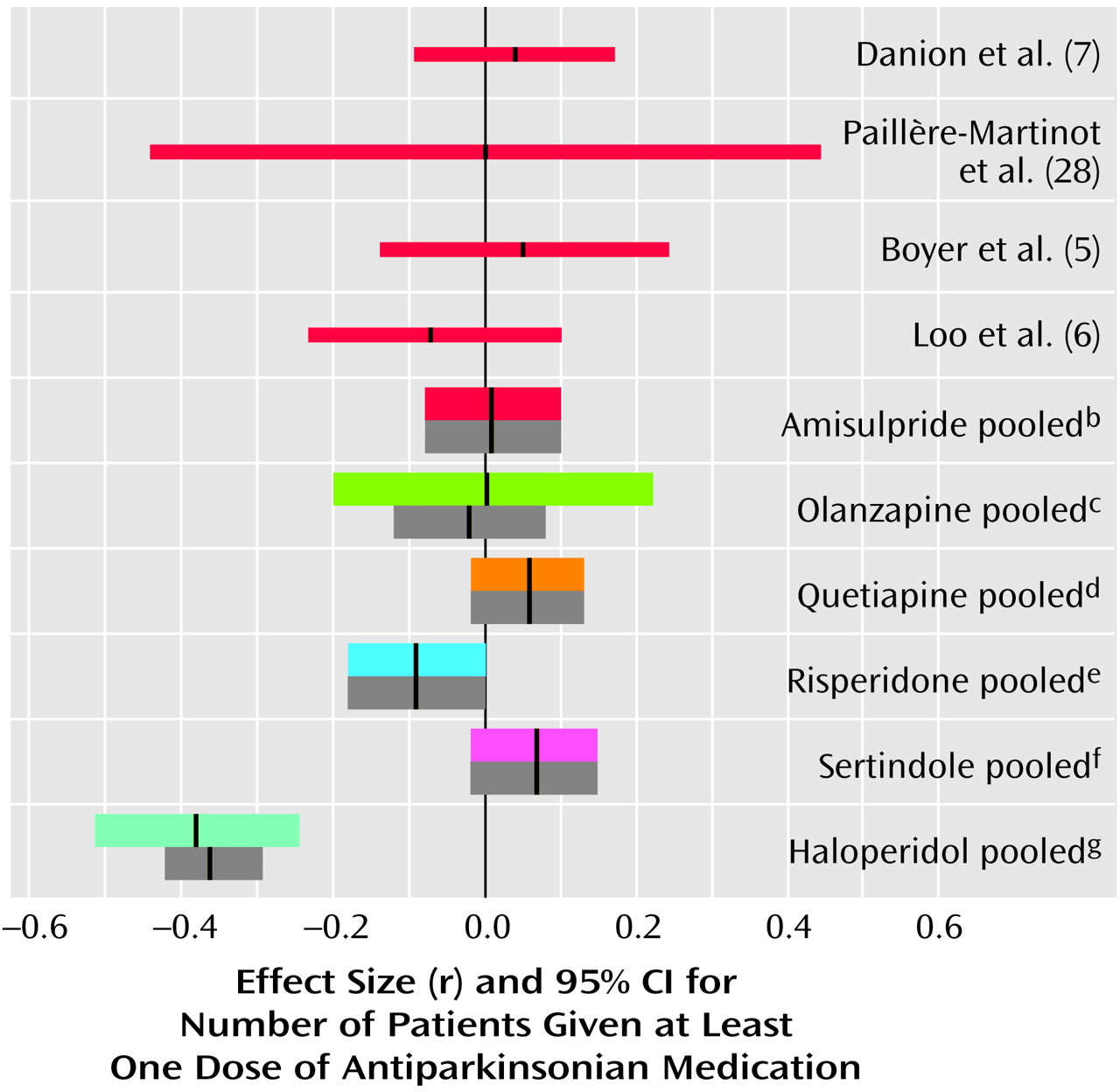

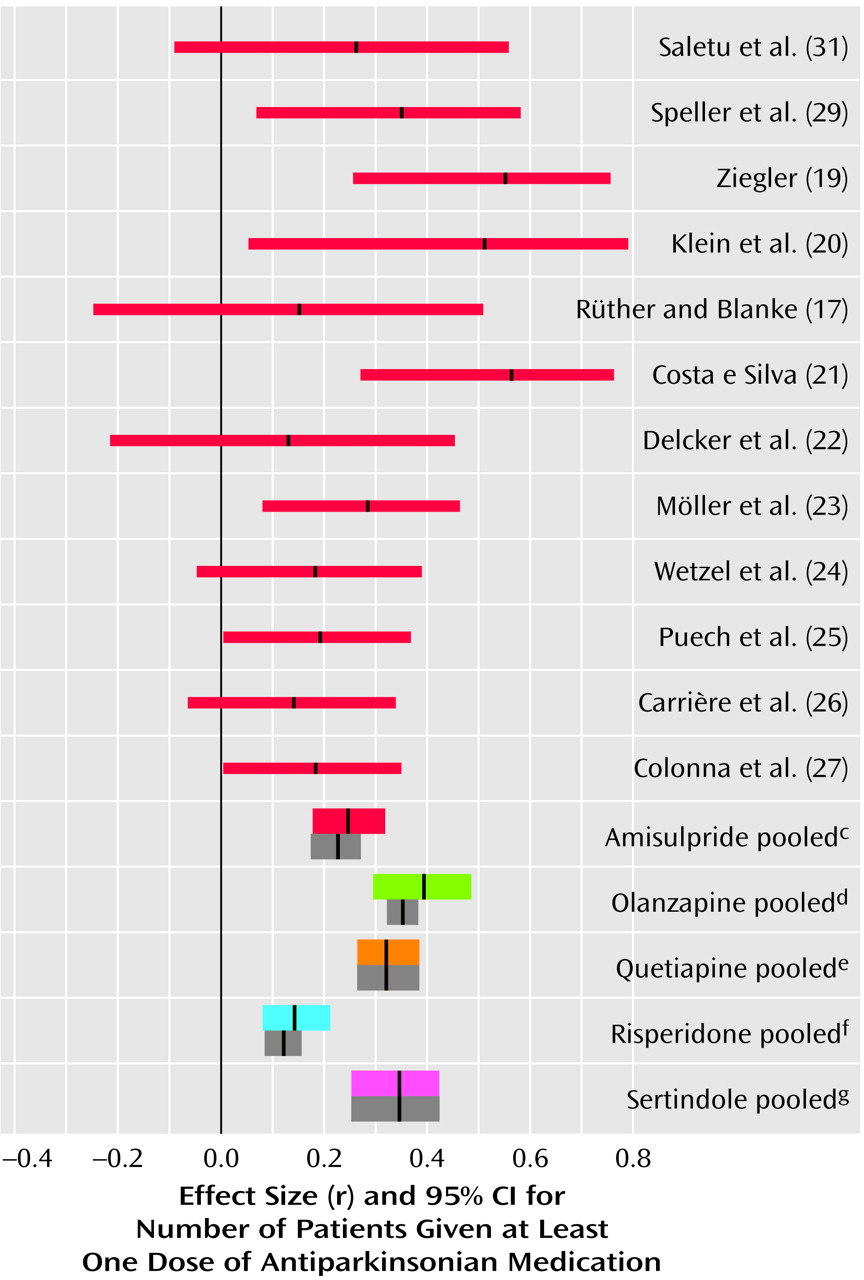

Use of Antiparkinsonian Medication

Amisulpride was not associated with significantly more use of antiparkinsonian medication than placebo (

Figure 4). It must be noted that in all placebo comparisons only low doses of amisulpride (50–300 mg/day) were used. We know of no comparisons of higher doses of amisulpride with placebo. However, amisulpride induced clearly fewer extrapyramidal side effects than conventional antipsychotics (

Figure 5). The mean effect size of r=0.25 lay between the effect sizes of risperidone (r=0.14) on the one hand and olanzapine (r=0.39), quetiapine (r=0.32), and sertindole (r=0.34) on the other. When only optimum doses of risperidone (4–8 mg/day) are considered, its effect size (r=0.17) approaches that of amisulpride. A significant heterogeneity of the amisulpride study results (χ

2=19.06, df=11, p=0.06) was resolved when the two studies that used the highest haloperidol doses

(20,

21) were excluded.

Dropout Rates

In the studies of acutely ill patients, significantly fewer patients treated with amisulpride dropped out than patients treated with conventional drugs (11 studies, r=0.17, 95% CI=0.08 to 0.26, z=3.68, p=0.0002). This superiority resulted from fewer dropouts due to adverse events (r=0.15, 95% CI=0.07 to 0.25, z=3.02, p=0.003), with the individual studies showing a consistent pattern. Only one study

(27) showed a trend in favor of haloperidol in this regard. This flexible-dose study led to significant study heterogeneity (χ

2=22.00, df=8, p=0.005), which was no longer apparent after its exclusion. No difference in dropouts due to inefficacy of treatment was found (r=0.01, 95% CI=–0.04 to 0.06, z=0.34, p=0.37).

In the studies of patients with predominantly persistent negative symptoms, fewer patients treated with amisulpride than with placebo left the studies earlier, whether because of ineffective treatment (r=0.17, 95% CI=0.07 to 0.27, z=3.13, p=0.002), because of adverse events (r=0.13, 95% CI=0.03 to 0.23, z=2.56, p=0.008), or for any reason (r=0.20, 95% CI=0.12 to 0.28, z=4.58, p<0.0001). No significant differences in dropout rates between amisulpride and conventional antipsychotics were found in three small studies of negative symptom schizophrenia (all dropouts: r=0.08, 95% CI=–0.08 to 0.23, z=0.96, p=0.34; patients who left because of ineffective treatment: r=0.11, 95% CI=–0.05 to 0.26, z=1.35, p=0.18; patients who left because of adverse events: r=0.04, 95% CI=–0.11 to 0.20, z=0.54, p=0.59). The use of a fixed-effects model did not lead to major changes here. The exact data can be obtained from us on request.

Sensitivity Analyses

The sensitivity analysis of only optimum doses (400–800 mg/day for acutely ill patients and 50–300 mg/day for patients suffering predominantly from persistent negative symptoms) did not lead to important changes. With the exception of dropouts due to adverse events, all effect sizes slightly increased in favor of amisulpride. For BPRS change, r=0.12, 95% CI=0.06 to 0.17; for change in negative symptoms, r=0.15, 95% CI=0.09 to 0.20; for antiparkinsonian medication, r=0.27, 95% CI=0.17 to 0.37; for global dropout rate, r=0.21, 95% CI=0.12 to 0.30; for dropouts due to adverse events, r=0.15, 95% CI=0.06 to 0.26; for dropouts due to ineffective treatment, r=0.02, 95% CI=–0.03 to 0.08. For the studies of patients with predominantly negative symptoms a sensitivity analysis was not necessary because no study used doses outside the optimum range (50–300 mg/day).

No significant changes were noted in a sensitivity analysis in which the earlier studies that used completer analyses were excluded.

Random- Versus Fixed-Effects Model

Compared to the fixed-effects model, the random-effects model sometimes widened the confidence intervals or led to slight changes of the mean effect sizes, but no substantial changes in the amisulpride results were obtained (see

Figure 1—

Figure 5. Unlike in the fixed-effects model, in the random-effects model the difference between olanzapine and conventional antipsychotics in terms of BPRS change and the borderline difference between quetiapine and conventional antipsychotics in terms of negative symptoms were no longer statistically significant. The reason for the substantially broader confidence interval of the effect size for olanzapine in the random-effects model was a significant heterogeneity among studies (χ

2=9.84, df=2, p=0.007). This disappeared when subtherapeutic doses (below 7.5 mg/day) were excluded (r=0.10, 95% CI=0.06 to 0.14, z=5.03, p<0.0001).

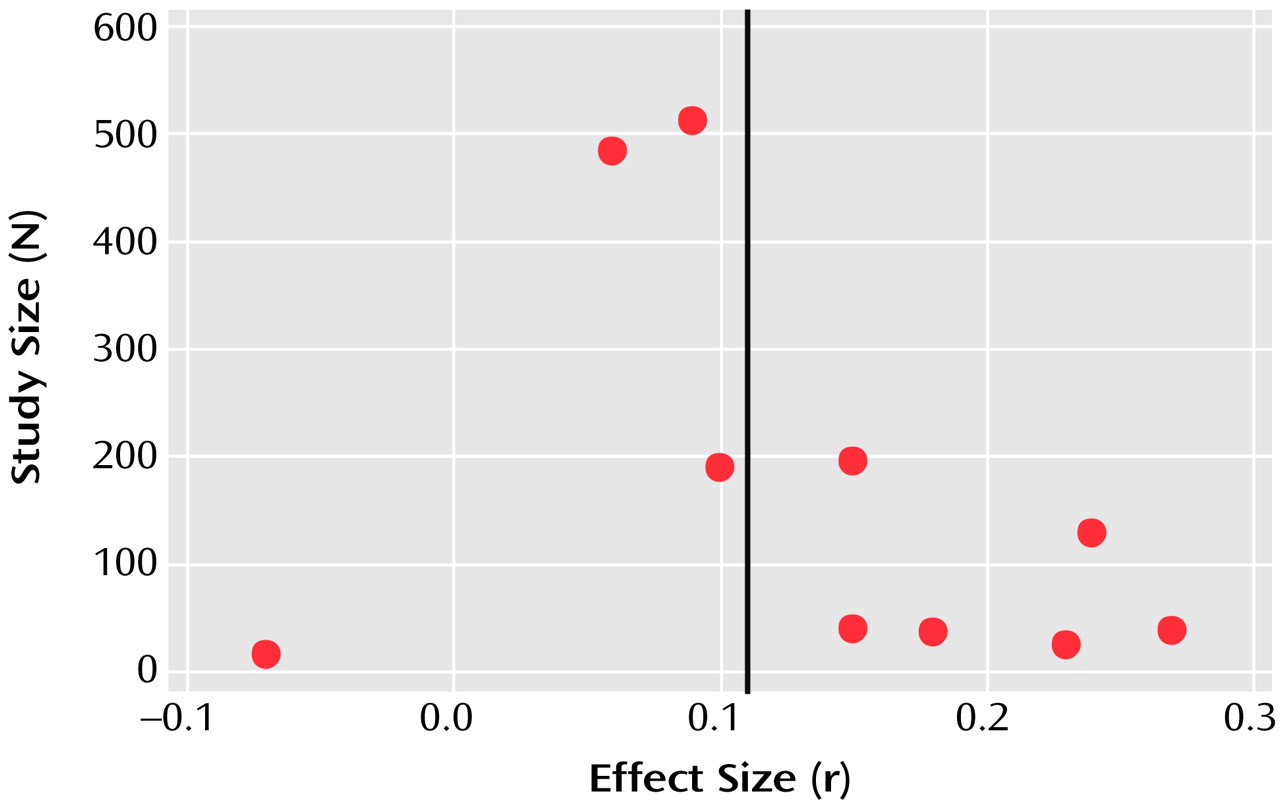

Exploration of Publication Bias

A funnel plot of the main outcome variable (mean BPRS score) revealed the potential of publication bias. Some small studies with negative results might not have been published (

Figure 6). However, according to the manufacturer, no further studies have been undertaken. According to the method of Rosenthal

(11), 62 unpublished studies would be necessary to reverse statistical significance. It is unlikely that so many studies have remained unpublished.

Discussion

Since the discovery that clozapine induces fewer extrapyramidal side effects and is more effective than conventional antipsychotics for the treatment of schizophrenia

(45,

46), psychopharmacological research has focused on the development of drugs that block central 5-HT

2 receptors more than D

2 receptors. Combined 5-HT

2/D

2 receptor antagonism is the most current explanation for the so-called “atypical” profile of some antipsychotics

(2). Although this concept is difficult to define

(47) and might be better understood as a continuum

(48), the most frequent requirements for atypicality are a low risk of extrapyramidal side effects and greater efficacy for negative symptoms. This meta-analysis showed that a highly selective dopamine antagonist with no effects on serotonergic receptors possesses atypical properties. Amisulpride is a well-studied drug (18 randomized controlled trials) and was consistently superior to conventional antipsychotics for acutely ill patients. Although a funnel plot suggests that publication bias cannot be excluded, further trials do not exist, according to the manufacturer, and would also be unlikely to change the overall effect.

The efficacy of amisulpride for negative symptoms has been examined more than that of the 5-HT

2/D

2 receptor antagonists. This does not mean that amisulpride is more effective than the other atypicals, but the slight and debatable superiority of the latter over typical antipsychotics has been derived only from studies of acutely ill patients

(3). Such studies do not allow a judgment about whether the superiority refers only to secondary or also to primary negative symptoms. Path analysis is a statistical method that has been used to rule out the effects of extrapyramidal side effects, depression, and positive symptoms on negative symptoms

(49–

51), but studies of patients suffering predominantly from persistent negative symptoms are more appropriate

(4). The placebo comparisons clearly showed that amisulpride is an effective treatment for negative symptoms. However, the mean effect size (r=0.26) is relatively small, so it is possible that no dramatic improvements might be seen in many patients. Furthermore, the few comparisons with typical drugs, which had insufficiently large study groups, failed to show a significant superiority of amisulpride. Similar preliminary results have been presented for a trial comparing quetiapine with a conventional antipsychotic

(52). Further large randomized controlled trials are indispensable for clarifying whether the new antipsychotics are really more effective for the treatment of primary negative symptoms.

The most consistent characteristic of atypicality is a low risk of extrapyramidal side effects. Like the 5-HT

2/D

2 receptor antagonists, amisulpride induced clearly less movement disorder than typical antipsychotics. More comparisons with drugs that have fewer extrapyramidal side effects than haloperidol would be desirable for all new antipsychotics. This meta-analysis can help to indirectly compare the new antipsychotics since direct comparisons are scarce. It suggests that amisulpride’s risk for extrapyramidal side effects lies between those of olanzapine, quetiapine, and sertindole on the one hand and risperidone on the other. When only optimum doses of risperidone (4–8 mg/day) are considered, its effect size is similar to that of amisulpride. This was also shown in a multicenter study in which risperidone, 8 mg/day, and amisulpride, 800 mg/day, showed similar occurrences of extrapyramidal side effects

(32). More direct comparisons of atypical antipsychotics are needed to clarify their risks of extrapyramidal side effects. Furthermore, similar to that of risperidone, amisulpride’s risk of extrapyramidal side effects is dose related, and in the dose-finding study by Puech et al.

(25) there was no significant difference in the rates of patients who received antiparkinsonian medication between the subjects who were taking 16 mg/day of haloperidol and those who were taking 1200 mg/day of amisulpride. We did not evaluate side effects other than extrapyramidal side effects, but a global indicator of amisulpride’s tolerability is the fact that significantly fewer patients left the studies early because of side effects than in the studies with conventional drugs. The main concern with amisulpride is the induction of substantial prolactin increase, although it is unclear whether this leads to higher rates of adverse endocrine events than found with other antipsychotics

(53). Weight gain is a problem of the 5-HT

2/D

2 antagonists. Allison et al.

(54) estimated mean weight gains for olanzapine, risperidone, and sertindole of 3.5 kg, 2.0 kg, and 2.5 kg within 10 weeks. Amisulpride was not included in this meta-analysis. Amisulpride was associated with relatively low mean weight gains in short-term studies (4–12 weeks) and long-term studies (6–12 months), i.e., 0.7 kg (SD=3.1) and 1.2 kg (SD=6.5), respectively (Sanofi-Synthélabo, data on file; see also reference

55).

The results of this meta-analysis must be seen in the light of several methodological problems. The small differences in the mean effect sizes for efficacy must not be regarded as real differences. A formal statistical comparison of mean effect sizes was not undertaken. Despite the similarity of studies on new antipsychotics, certain differences in study designs, such as slightly different inclusion criteria, study durations, comparators, or dose regimens (e.g., dose titration versus fixed doses), would make such statistics inappropriate. This points to a general problem of meta-analysis, which is an elegant approach for combining the data of several studies but is not adequate for dealing with the particular features of the individual studies. Further such design differences relate to measurement intervals and analysis methods, what was meant by “intent to treat,” and the way dropouts were handled. The use of continuous outcome measures is problematic because it is impossible to assure normal distribution with absolute certainty. An analysis of response rates was not possible because of a high variability of criteria within the studies of one new antipsychotic and between studies of different new antipsychotics (e.g., 20%, 40%, or 50% reduction in BPRS score) and because it would not have been possible to examine negative symptoms. With the exception of some data in the oldest studies, which could not be obtained owing to changes in ownership, a complete amisulpride data set was available for the meta-analysis, whereas not all data were received for the update of the other drugs, despite our requests. These data might have led to slight changes but would not have vitiated the global results, i.e., that amisulpride leads to clinical effects similar to those of the other atypical antipsychotics. A recent analysis

(56) of 163 randomized controlled trials (18,585 patients) included in the Cochrane reviews on conventional and new antipsychotics showed a constant increase in dropout rates from the 1950s to the present. In the short-term studies on amisulpride, risperidone, olanzapine, quetiapine, and sertindole, global dropout rates of 22%, 30%, 43%, 46%, and 47% were found. It should be kept in mind that the higher the dropout rate, the more difficult it is to interpret the data, since assumptions such as the last-observation-carried-forward model must be made. In this model, when a patient leaves the study before completion, data from his or her last assessment are used in the statistics. Given that the conventional antipsychotics are usually less tolerable, patients who take these drugs drop out of the studies earlier. In the end effect this can give the false appearance that the atypical antipsychotic is more effective than the conventional one. In a meta-regression of 52 trials, Geddes et al.

(57) showed that the advantages in terms of efficacy and dropouts of the atypical antipsychotics disappear when doses below 12 mg/day of haloperidol (or equivalent) are used. Finally, many of the patients included in the trials had previously had partial responses to conventional antipsychotics, and so many of those in the groups receiving new antipsychotics may just have benefited from a switch to a compound with a different receptor binding profile. These limitations must be kept in mind when considering any superiority in efficacy of the new antipsychotics found in this meta-analysis.

The main conclusion of this meta-analysis is that combined 5-HT

2/D

2 receptor antagonism is not the only mechanism that makes an antipsychotic atypical. Mesolimbic selectivity of dopamine receptor blockade is another explanation for the low risk of extrapyramidal side effects associated with some antipsychotics. Such a selectivity has been described not only for amisulpride but also for sertindole

(58), olanzapine

(59), and quetiapine

(60). Whereas the high efficacy of low doses of amisulpride for negative symptoms has been explained by its action on presynaptic dopaminergic autoreceptors, the inhibition of 5-HT

2 receptors by the other atypicals leads to enhanced dopamine release in the frontal lobe and possibly a reduction of negative symptoms. Some other models currently under examination are a selective affinity to D

4 receptors

(61), a selective affinity to D

3 receptors

(62), partial dopamine agonism

(63), and multireceptor effects similar to those of clozapine

(64).

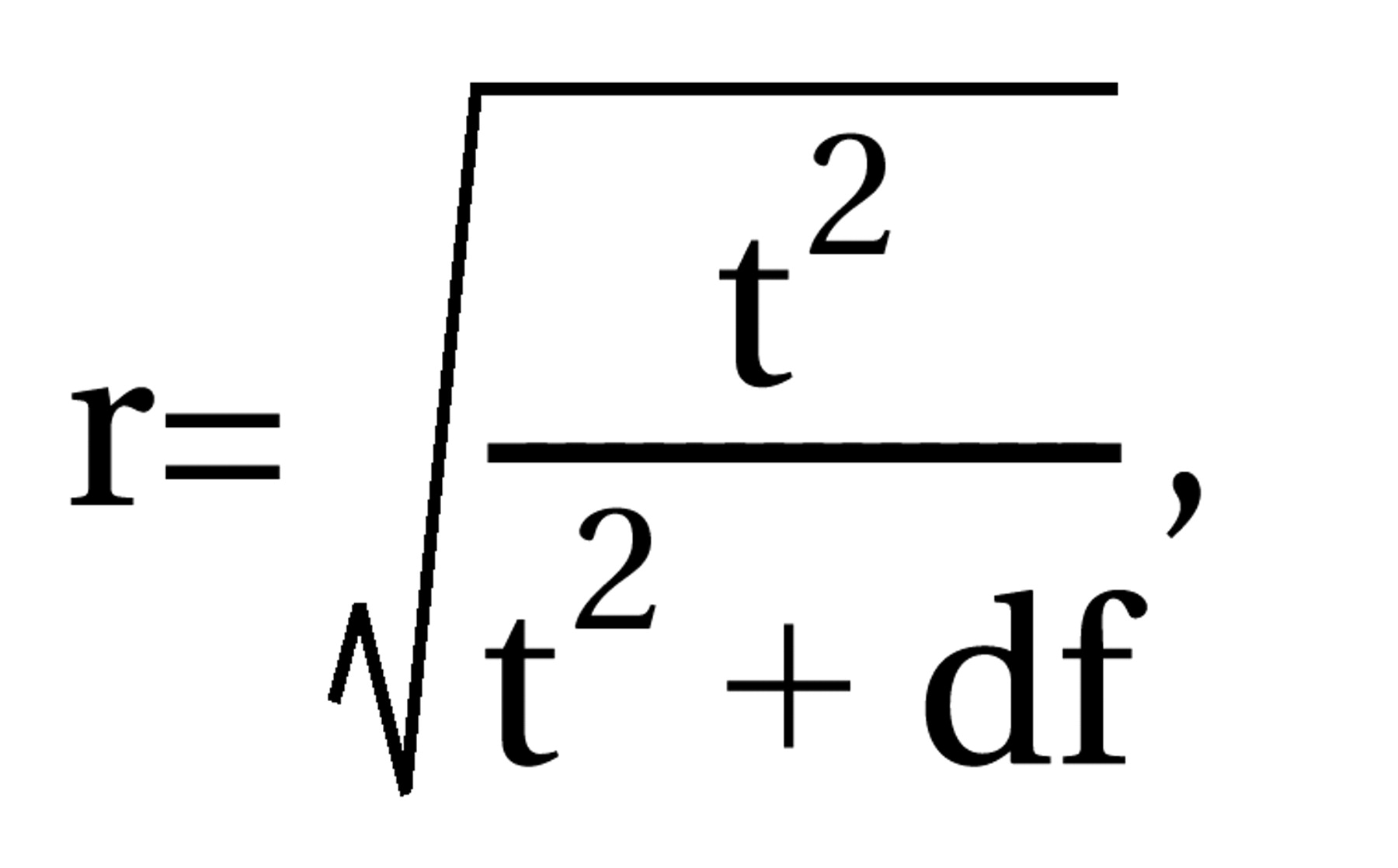

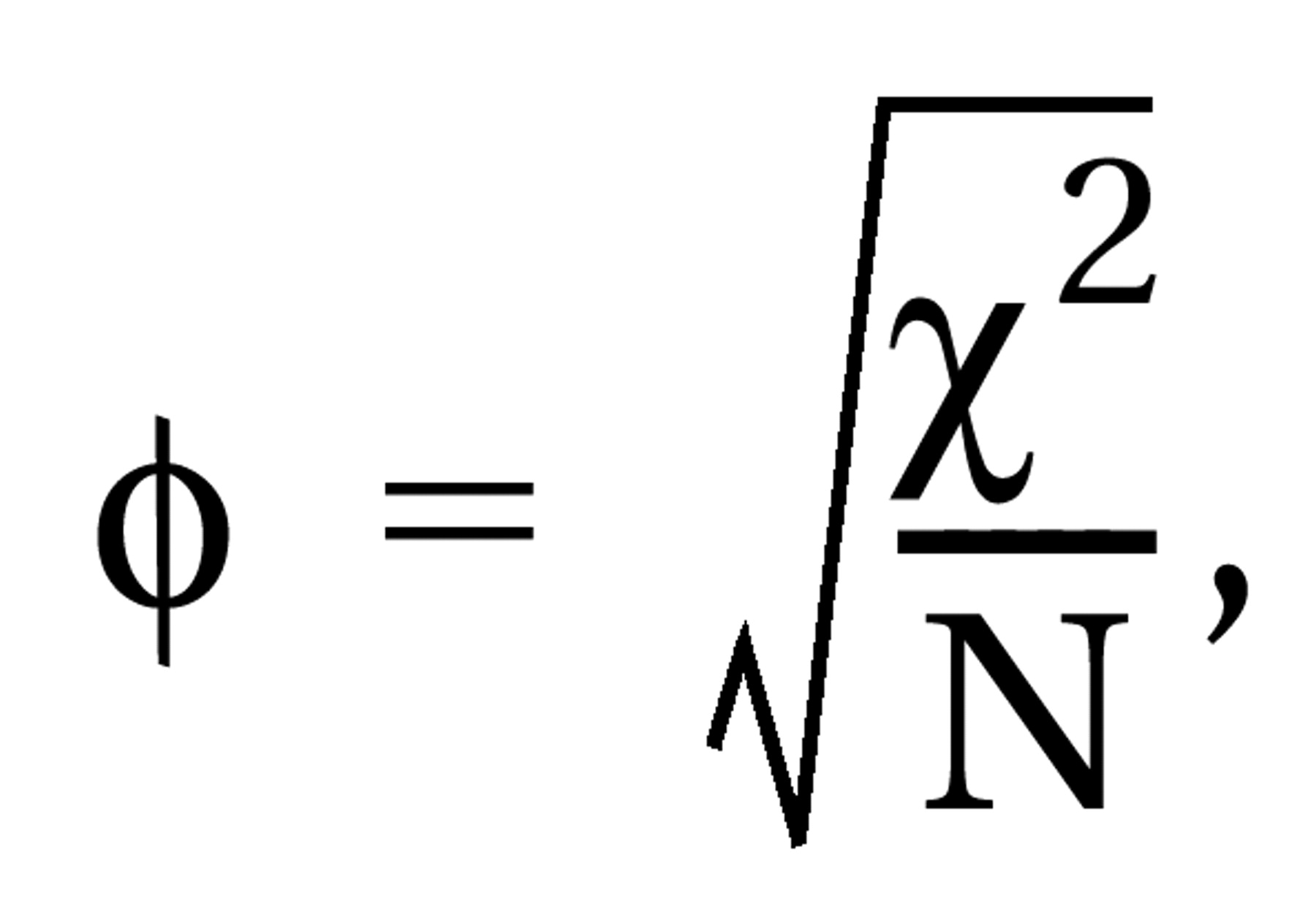

where df=N1+N2–2, N1 and N2 are the numbers of patients in the control and intervention groups, and t=result of the t test. For dichotomous data, chi-square tests using 2×2 tables were calculated to obtain phi (φ) according to the formula

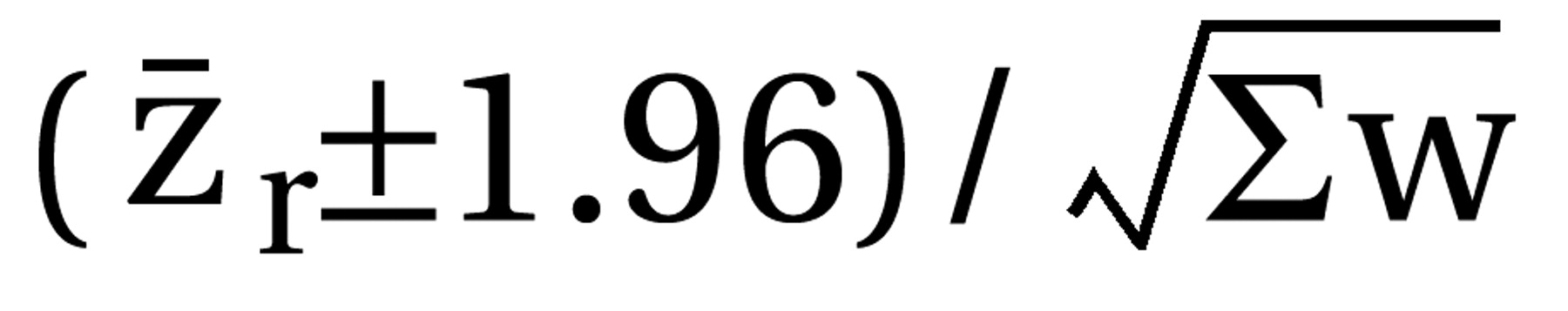

where df=N1+N2–2, N1 and N2 are the numbers of patients in the control and intervention groups, and t=result of the t test. For dichotomous data, chi-square tests using 2×2 tables were calculated to obtain phi (φ) according to the formula  where χ2=result of the chi-square test and N=total number of patients in both groups. Phi corresponds to Pearson’s correlation coefficient for continuous data. All statistical calculations involving correlation coefficients (calculation of means, confidence intervals, etc.) were made on the basis of zr, i.e., Fisher’s z transformation for correlation coefficients. Results were transformed back to r. For studies that compared several doses of amisulpride with a control condition, the different dose groups of amisulpride were pooled; i.e., for continuous data, the mean effect r achieved by the different doses was calculated, and for dichotomous data, all patients treated with amisulpride were considered as a single group in the chi-square test. For combining the effect sizes of the single studies, the random-effects model according to DerSimonian and Laird (15) was used. This model is usually more conservative than fixed-effects models because it takes into account variability between studies. For this, a chi-square test of homogeneity was calculated with

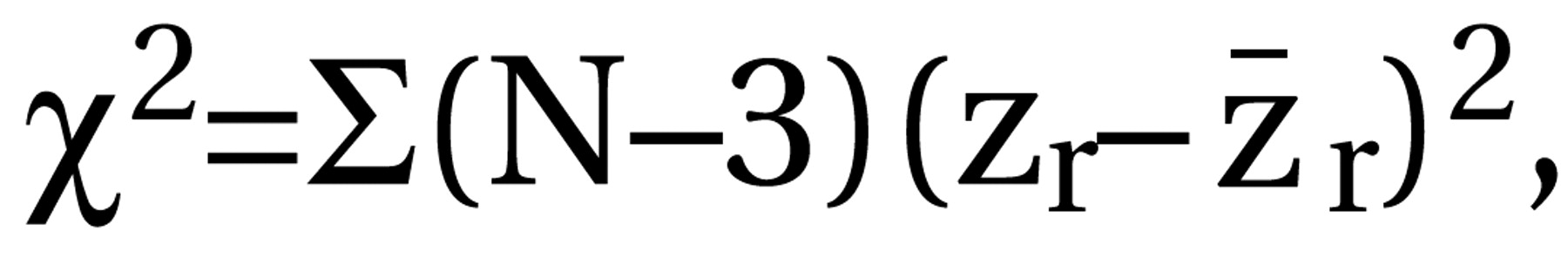

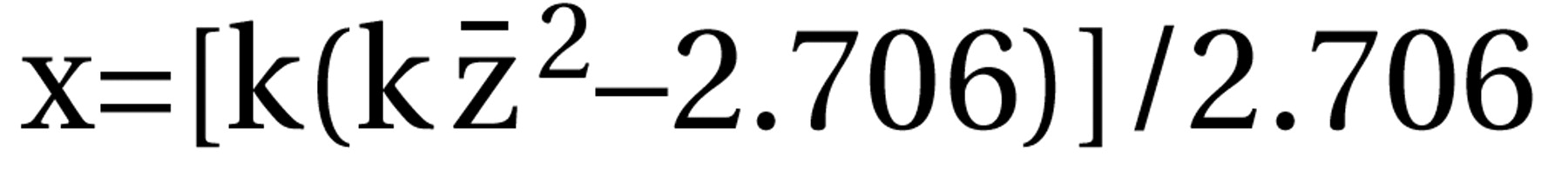

where χ2=result of the chi-square test and N=total number of patients in both groups. Phi corresponds to Pearson’s correlation coefficient for continuous data. All statistical calculations involving correlation coefficients (calculation of means, confidence intervals, etc.) were made on the basis of zr, i.e., Fisher’s z transformation for correlation coefficients. Results were transformed back to r. For studies that compared several doses of amisulpride with a control condition, the different dose groups of amisulpride were pooled; i.e., for continuous data, the mean effect r achieved by the different doses was calculated, and for dichotomous data, all patients treated with amisulpride were considered as a single group in the chi-square test. For combining the effect sizes of the single studies, the random-effects model according to DerSimonian and Laird (15) was used. This model is usually more conservative than fixed-effects models because it takes into account variability between studies. For this, a chi-square test of homogeneity was calculated with  where zr=Fisher’s z of r and r. Then tau2 was estimated by using the formula

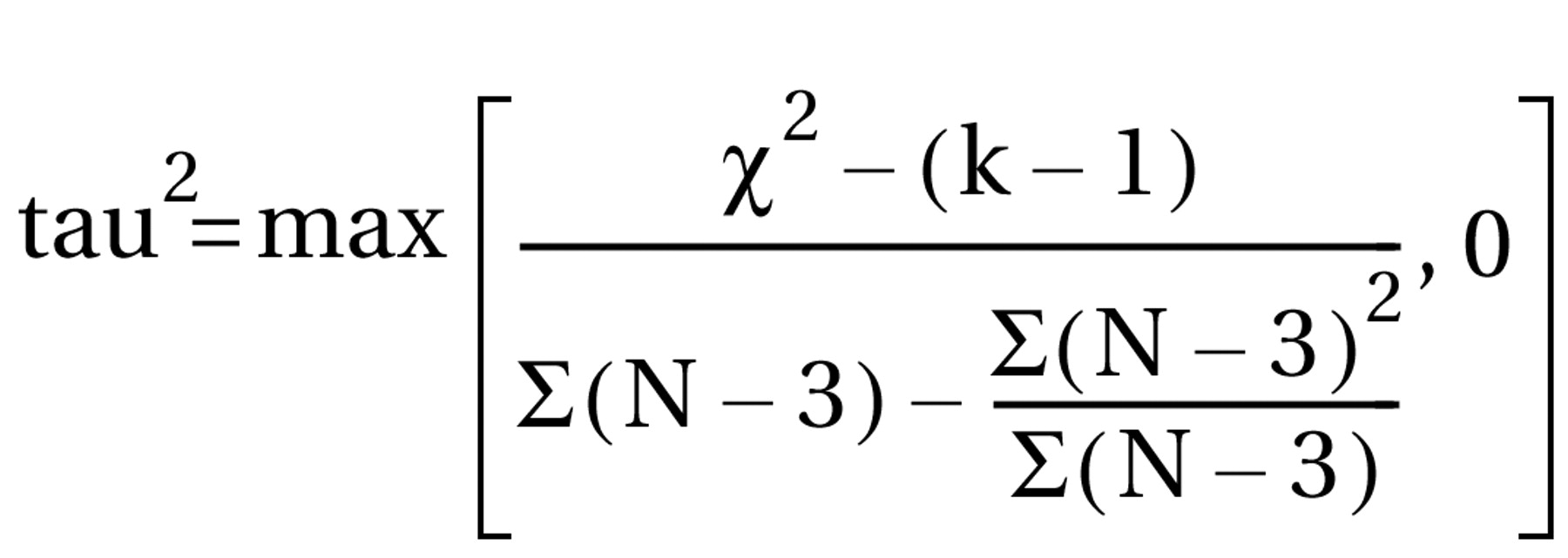

where zr=Fisher’s z of r and r. Then tau2 was estimated by using the formula  with k–1=number of degrees of freedom. Tau2 was used for the weighting of the single studies by w=(N–3)/{1+[(N–3)*tau2]}. In cases where the heterogeneity statistic is less than or equal to k–1, tau2 is zero and the weights are the same as in the fixed-effects model (see the following). The weighted mean z was calculated as [S(zr*w)]/Sw and transformed back to r̄ as the coefficient of the effect size. To maintain comparability with the previous results (3), the mean effect sizes obtained by a fixed-effects model are also presented (thick gray bars in the figures). Here N–3 is used for weighting the individual studies irrespective of heterogeneity among studies. The results are presented as (mean) effect size r along with the 95% confidence interval (CI) calculated as

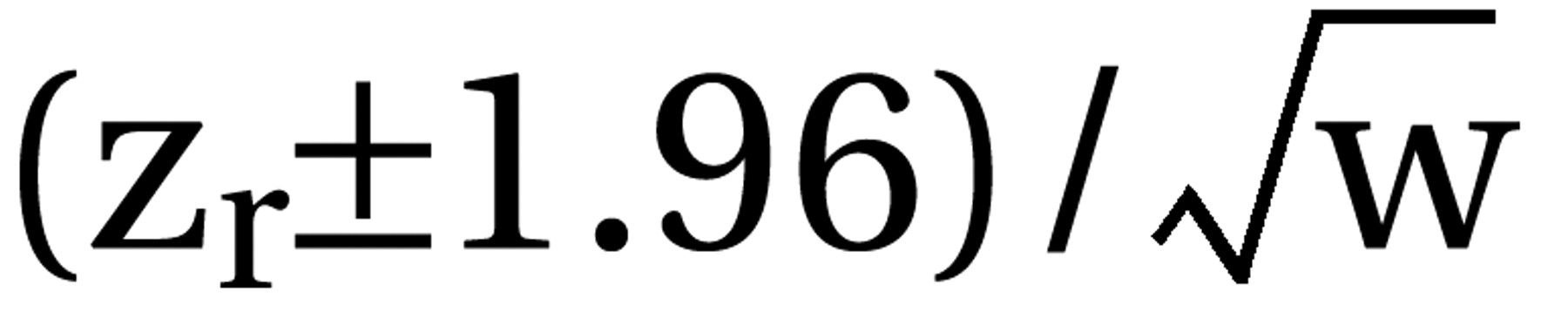

with k–1=number of degrees of freedom. Tau2 was used for the weighting of the single studies by w=(N–3)/{1+[(N–3)*tau2]}. In cases where the heterogeneity statistic is less than or equal to k–1, tau2 is zero and the weights are the same as in the fixed-effects model (see the following). The weighted mean z was calculated as [S(zr*w)]/Sw and transformed back to r̄ as the coefficient of the effect size. To maintain comparability with the previous results (3), the mean effect sizes obtained by a fixed-effects model are also presented (thick gray bars in the figures). Here N–3 is used for weighting the individual studies irrespective of heterogeneity among studies. The results are presented as (mean) effect size r along with the 95% confidence interval (CI) calculated as  for the single studies and

for the single studies and  for the mean confidence intervals, each limit zr back-transformed to its corresponding r. Thus, positive r values indicate effects favoring the new antipsychotic. Only the updated mean effect sizes for the 5-HT2/D2 antagonists and the results of the new studies on them are presented in the figures. We used z tests to assess the statistical significance of the mean effect sizes. This statistical significance was assumed when p values were less than 0.05 (two-tailed).

for the mean confidence intervals, each limit zr back-transformed to its corresponding r. Thus, positive r values indicate effects favoring the new antipsychotic. Only the updated mean effect sizes for the 5-HT2/D2 antagonists and the results of the new studies on them are presented in the figures. We used z tests to assess the statistical significance of the mean effect sizes. This statistical significance was assumed when p values were less than 0.05 (two-tailed). with k=number of studies combined and z̄=mean z obtained for the k studies (11).

with k=number of studies combined and z̄=mean z obtained for the k studies (11).