Because there are no data on individuals’ attitudes, these proposals are based in part on assumptions concerning what individuals think about participating in research if they became impaired. For instance, proposals to allow impaired adults to be enrolled only in research on conditions from which they suffer are based largely on the assumption that individuals are less willing to participate in research on conditions from which they do not suffer. Similarly, proposals for research proxies rely on assumptions concerning individuals’ willingness to allow others to make research decisions for them. Proposals that would bar impaired adults from research that offers no potential for medical benefit assume that individuals are unwilling to participate in such research.

Method

Study Group

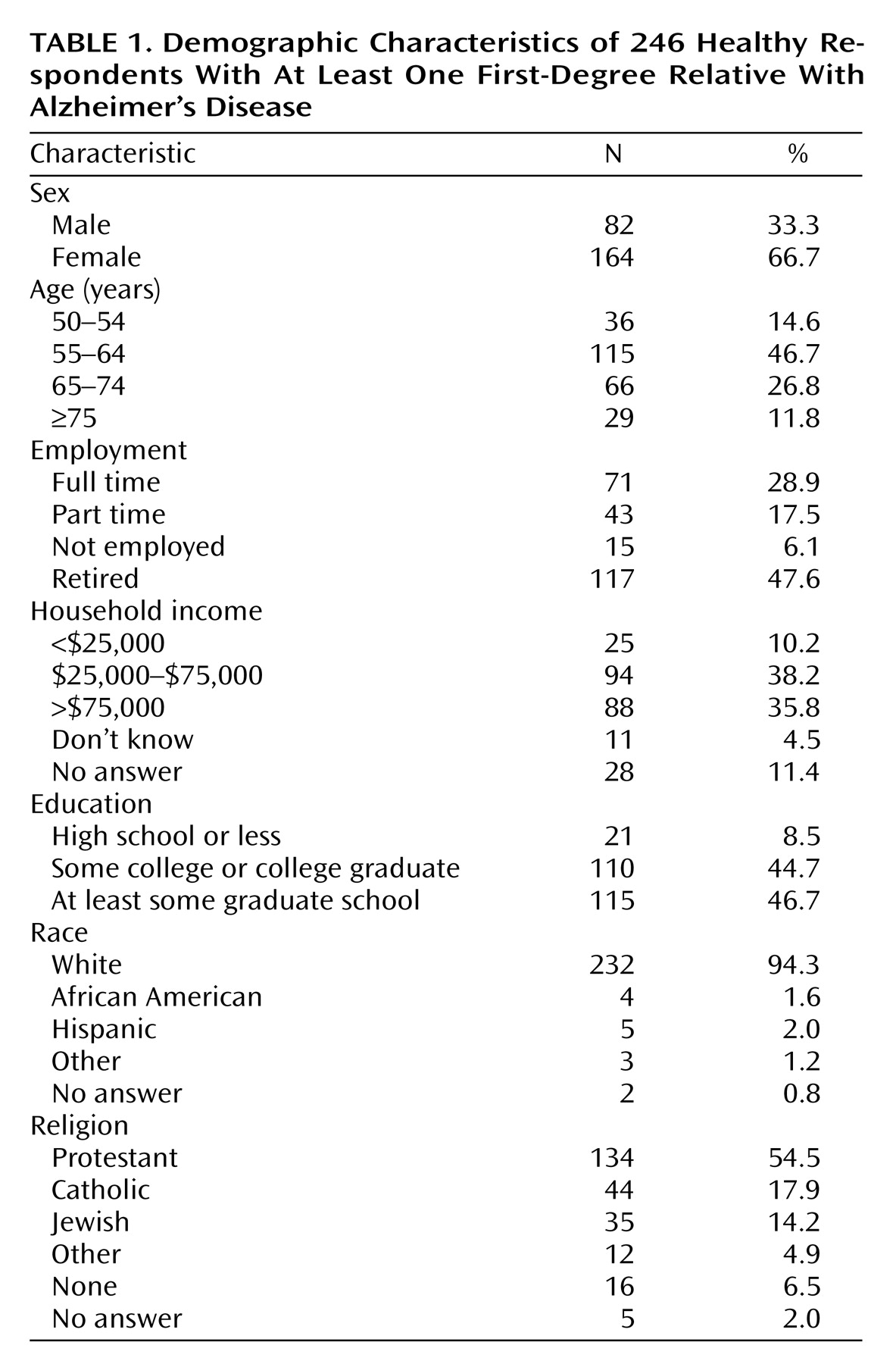

To ensure the respondents were familiar with clinical research and decision making for those with cognitive impairment, we targeted individuals who had participated in clinical research for subjects who have a close relative with Alzheimer’s disease. Respondents were drawn from studies of healthy individuals who have at least one first-degree relative with Alzheimer’s disease being conducted at four geographically dispersed research centers: Stanford University, Duke University, the University of California, Los Angeles, and the National Institutes of Health.

All individuals participating in these studies were sent a letter explaining the survey, along with a self-addressed, stamped “opt-out” card. Those who did not return the card within 2 weeks were contacted by telephone. After explanation of the study, those who consented to participate were interviewed by specially trained interviewers from the Center for Survey Research, Boston. Of the 263 eligible respondents, 246 (94%) completed the survey.

The protocol was approved by the institutional review boards at the University of California, Los Angeles; Stanford University; Duke University; the University of Massachusetts, Boston; and the National Institute of Mental Health.

Survey Development

Following review of the literature, we developed a draft survey instrument that was revised on the basis of input from experts on research ethics and Alzheimer’s disease. The instrument was then administered in person to elderly individuals as a cognitive comprehension and behavioral pretest. The final survey instrument (available from the first author) addressed five domains: 1) clinical research experience, 2) general attitude toward clinical research, 3) attitude toward research advance directives, 4) willingness to participate in clinical research if unable to consent, and 5) sociodemographics.

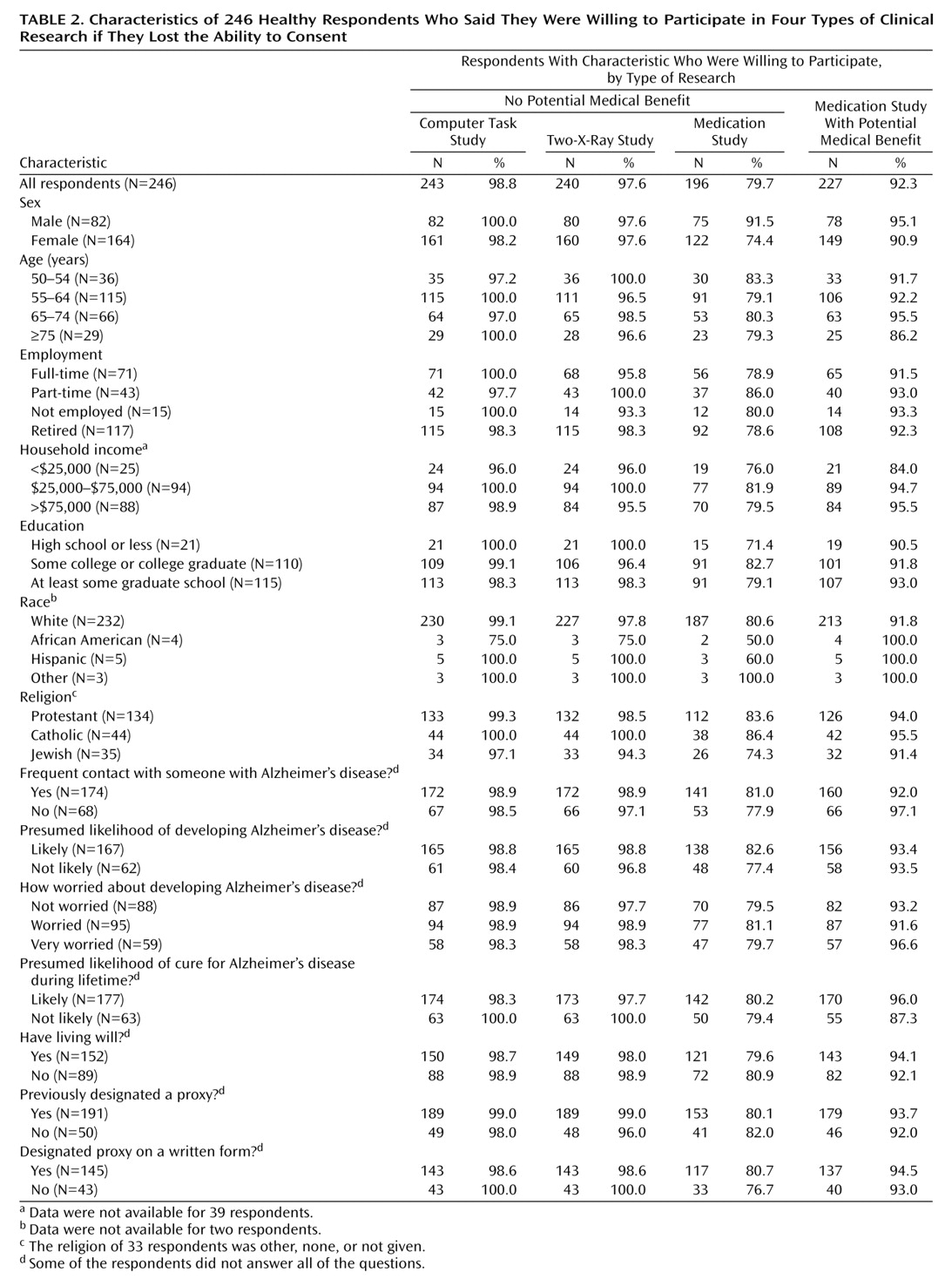

To assess individuals’ willingness to participate in clinical research if they lost the ability to consent, respondents were asked how likely they would be to give advance permission to be enrolled in five kinds of research: 1) “taking experimental medication that might improve your memory,” 2) “taking experimental medication that would not help you, but might lead to knowledge that would help others,” 3) “answering questions on a computer, if the study could not help you but might lead to knowledge that would help others,” 4) “an Alzheimer study involving two X-rays, if the study could not help you but might lead to knowledge that would help others,” 5) “a study involving two X-rays that would not help you with your Alzheimer’s disease, but could help research on some other disease.”

These examples were chosen to represent the three risk levels included in most proposals: 1) minimal risk, 2) minor increment over minimal risk, and 3) more than a minor increment over minimal risk. The computer study represented a minimal risk study. There is no accepted definition of “minor increment” over minimal risk. In the only article we found on assessments of risk categories, a bone scan was deemed a minor increment over minimal risk by many respondents

(22). We assumed that bone scans would be unfamiliar to many of our respondents. Therefore, to represent a minor increment over minimal risk study, we choose a study involving two X-rays, which pose radiation levels roughly similar to a bone scan. The medication study represented a study with more than a minor increment over minimal risk.

Research Advance Directive Development and Administration

Despite discussion of research advance directives, no standard form exists. We developed a draft based on existing clinical advance directives and the proposals for research advance directives

(11–

17). This draft form was reviewed by experts on research with impaired subjects and revised. At the end of the telephone survey, respondents were told that we would send them a research advance directive within 14 days and that they could return this form to their home research institution using an enclosed self-addressed, stamped envelope. All forms returned to the subjects’ home institutions within 1 year were counted and analyzed for content.

Statistical Analysis

Associations were tested by using a Mantel-Haenszel chi-square test for two-by-k tables when the k categories were ordered. Fisher’s exact tests (two-tailed) were used for all two-by-two tables.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this study provides the first systematic assessment of individuals’ attitudes toward five of the most prominent proposed safeguards regarding the consent process for research with adults unable to consent. Many respondents said they were willing, if they became impaired, to participate in clinical research that would not help them; only one in seven respondents completed and returned a research advance directive; almost half of all respondents had discussed their research preferences with their family.

Some have argued that enrolling impaired adults in research that offers no compensating potential for medical benefit is inherently exploitative, even when the research cannot be conducted with adults who are able to consent. These arguments assume that enrollment of impaired individuals in research that offers no potential for medical benefit conflicts with their competent preferences—the preferences they had when they were able to understand. Against this, our data suggest that such research may be consistent with the competent preferences of at least some individuals. At the same time, our data cannot be used to estimate how many Americans have this view. Indeed, the majority of Americans may be unwilling to participate in research that offers no potential for medical benefit.

Our data suggest that enrolling adults who are unable to consent in research that offers no potential for medical benefit is not inherently exploitative and, therefore, should not be prohibited altogether. However, the possibility that many individuals may be unwilling to participate in such research suggests that specific individuals should be enrolled only when there is sufficient evidence that enrollment is consistent with their competent preferences.

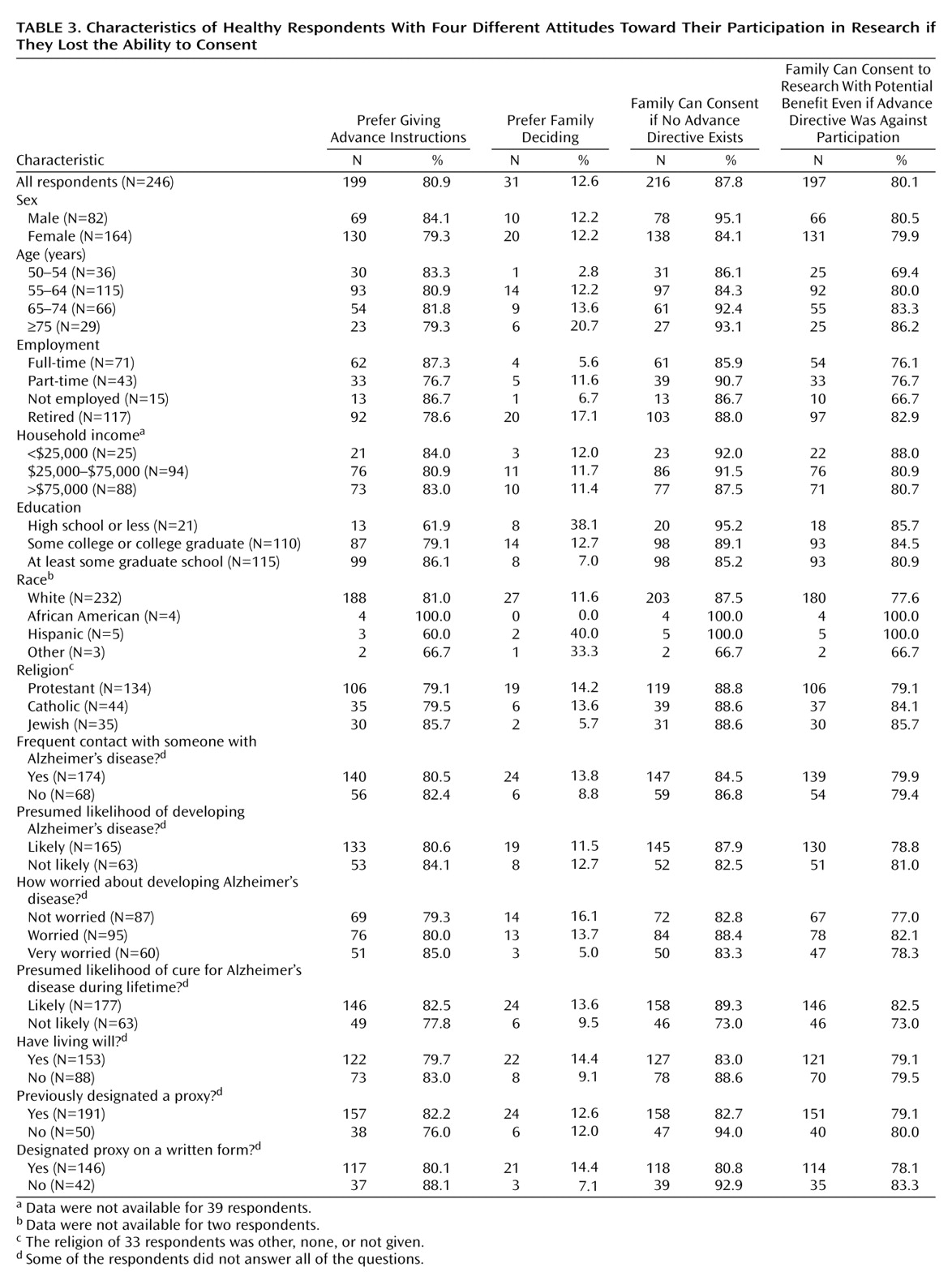

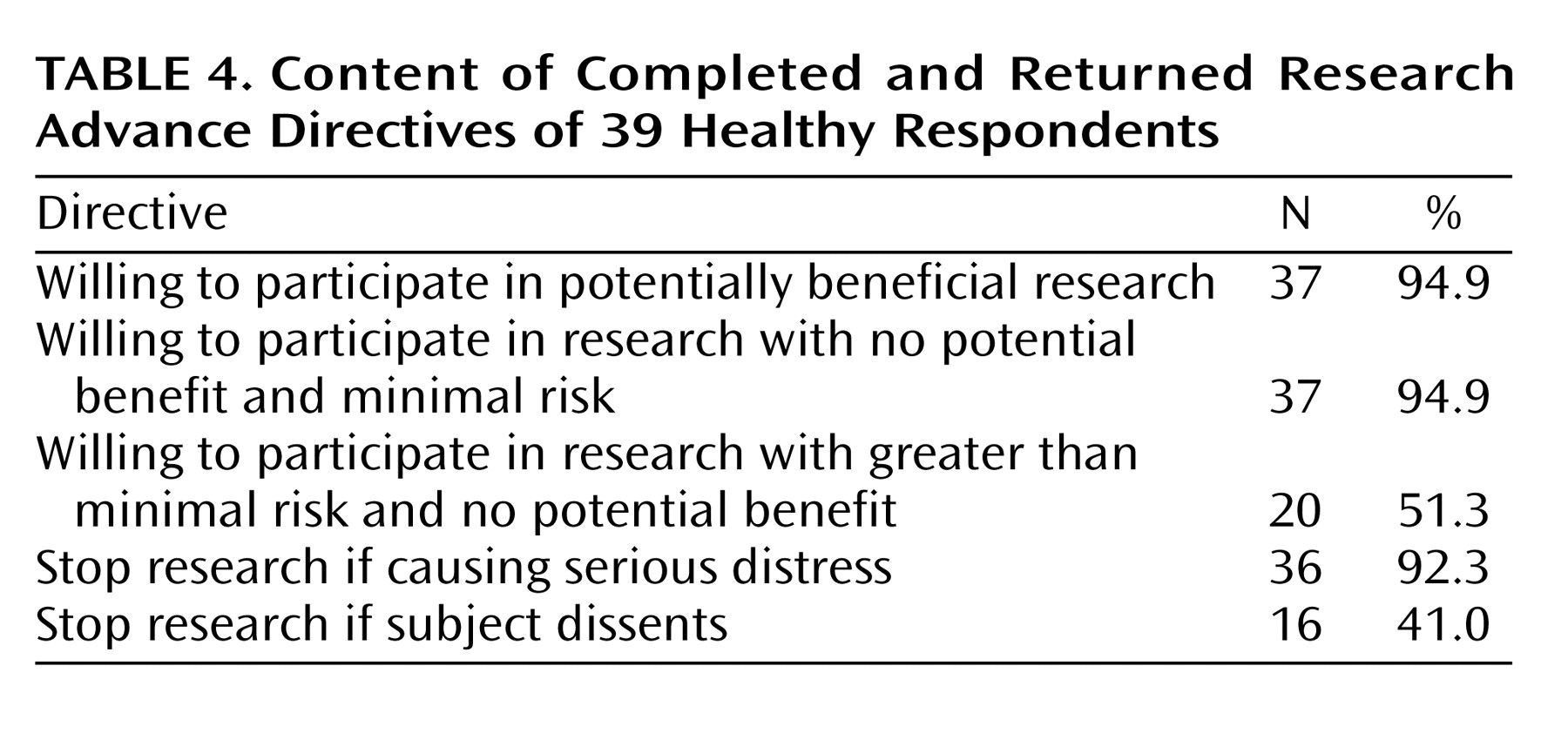

Several groups would mandate that individuals’ competent preferences must be documented in a formal research advance directive. Although the overwhelming majority of our respondents supported the use of research advance directives, only one in seven completed and returned a research advance directive to their home institution. This failure is striking given that respondents 1) had an overwhelmingly positive attitude toward clinical research, 2) had already enrolled in clinical research on Alzheimer’s disease, 3) were overwhelmingly willing to participate in clinical research if impaired, and 4) recently completed our phone survey, which detailed the difficulties involved in obtaining informed consent from impaired individuals and the ways in which research advance directives could address these difficulties. These factors suggest that the average American is unlikely to be more willing to complete a research advance directive; therefore, requiring that individuals’ competent preferences be documented in a research advance directive could jeopardize important research.

In contrast to individuals’ failure to execute a formal research advance directive, almost half of all respondents reported explicitly discussing their research preferences with their family. Of course, many impaired individuals, especially those unfamiliar with clinical research, may never discuss their research preferences with others. Hence, allowing research enrollment of impaired adults on the basis of sufficient evidence of their competent preferences, without stipulating how such evidence must be documented, will not ensure that all impaired individuals who wanted to enroll in clinical research will be able to do so. Nonetheless, our data suggest that this approach is more likely to lead to research decisions consistent with individuals’ competent preferences.

Some have argued that only individuals who have been formally assigned to serve as a research proxy should be able to enroll impaired adults in clinical research. Against this, 88% of our respondents supported allowing their families to make research decisions for them. In contrast, respondents who had assigned someone to make clinical decisions were overwhelmingly willing to participate in research once impaired, but they were unwilling to allow their families to make research decisions for them. Although not supported directly by our data, these facts suggest that individuals who have assigned someone to make clinical decisions for them if they lose the ability to consent prefer having these individuals make their research decisions as well.

One possibility would be to incorporate statements about individuals’ research preferences on clinical advance directives. For instance, individuals could be asked to specify whether the person they assign to make clinical decisions for them should be allowed to make research decisions as well. Including statements about research participation on clinical advance directives might also prompt individuals to discuss their research preferences with their proxies and families, thus increasing knowledge of individuals’ competent research preferences.

The possible limitations of relying exclusively on individuals’ preferences as specified in formal advance directives are highlighted by the fact that 80% of our respondents would allow their families to enroll them in research that offers a potential for medical benefit even when their advance directive opposed research participation. This finding suggests that competent preferences expressed in formal research advance directives should not automatically be regarded as definitive. Instead, these expressions should be evaluated in the context of any other evidence of individuals’ competent preferences, such as discussions with family members, as well as other reasons (e.g., the study offers potential medical benefit) to think the individual would or would not want to be enrolled in the study in question.

A number of proposals would prohibit the enrollment of impaired adults in research on conditions from which they do not suffer. However, almost identical numbers of respondents were willing to participate in two-X-ray studies on conditions from which they suffered and two-X-ray studies on other conditions (98% versus 97%). This suggests that, for the purposes of deciding whether they are willing to be enrolled in clinical research once impaired, many individuals may not be concerned primarily with the condition being studied. Instead, many individuals may base these decisions on the risks and potential benefits that the research offers to them, as well as the extent to which their research participation may help others.

There is widespread agreement that impaired individuals should be removed from clinical research if they object. Surprisingly, half of all the respondents who returned a research advance directive stated that their research participation should not be stopped if, once impaired, they say they want it stopped.

This finding should be evaluated with caution. Less than one in seven respondents returned a research advance directive. Moreover, these individuals may have been concerned that a single objection would eliminate them from potentially beneficial research. In addition, respondents may not have fully appreciated subjects’ rights to withdraw from clinical research. Nonetheless, these data appear to contradict proposals that would remove impaired adults from research at the first sign of dissent. One possibility would be to halt temporarily and obtain an independent assessment of the research participation of impaired adults who object. While this approach is more likely to respect individuals’ competent preferences, the principle of beneficence suggests that the sustained objections of impaired individuals should be respected irrespective of their competent preferences.

The present data are subject to several important limitations. First, as with any initial study, further research will be needed to assess whether the current findings generalize to other populations. In particular, it will be important to assess whether individuals at risk for other disabling conditions, such as schizophrenia and stroke, have similar attitudes. In addition, since we surveyed individuals older than 50 years of age, some of our results may be due to a generational effect. Although we did not find any statistically significant effects based on race, they may be seen in future studies that include more minority subjects.

We assessed the execution rate of research advance directives by sending individuals a form and asking them to fill it out. Future research should consider whether more active approaches, such as intervention by personal physicians, might result in higher execution rates. Finally, the percentage of individuals willing to participate in no-benefit research was lower among those who completed and returned a research advance directive than among all those who participated in the telephone interview. In the light of the very low return rate for the advance directives, future research should assess whether this is a statistical artifact or whether individuals who complete a research advance directive are less willing to participate in no-benefit research.