Lithium discontinuation may have significant negative consequences for patients with bipolar disorder, particularly in the first year after treatment is terminated

(1,

2). After discontinuation, the risk of recurrence of affective illness, and particularly of manic episodes, appears to be greater than that expected in untreated patients

(3). Overall morbidity and suicidal behavior in particular are also greater

(4). This elevated risk has been demonstrated in a group of pregnant women and nonpregnant comparison subjects

(5) and in adolescents with bipolar I disorder

(6). However, not all studies have shown this elevation

(7).

The purpose of this investigation was to examine the apparent risk posed by an abrupt change in lithium level. We reanalyzed data from a study of the efficacy of low- versus standard-dose lithium in maintenance therapy for patients with bipolar disorder

(13) to examine the potential confounding influence of rapid change in lithium dose on the effects of the random assignment to treatment groups. In that study, stable, euthymic patients with bipolar disorder who were being treated with lithium were randomly assigned to maintenance treatment with either standard or low serum lithium levels. However, as that study was performed before the effects of abrupt discontinuation were described, the original analysis did not include an interaction effect between the baseline and the randomly assigned lithium levels. On the basis of the more recent data of Faedda and Baldessarini and colleagues

(8,

9), we hypothesized that the patients who experienced a dose reduction would be at greater risk for recurrence than those who continued to receive their original dose. We investigated this hypothesis by examining the interactive effects of previous dose levels on the outcome of a standard- versus a low-dose strategy for maintenance treatment.

Method

Original Study Method

Participants in the original study by Gelenberg et al.

(13) met Research Diagnostic Criteria (RDC) and DSM-III criteria for bipolar illness with at least one episode of mania; were age 18–75 years; and were clinically stable, with at least 6 months elapsed from the onset of their last mood episode and 2 months or more of recovery. Subjects with rapid cycling (four or more episodes per year) or those who had not tolerated lithium levels of at least 0.6 meq/liter for 2 months were excluded. After complete description of the study to the subjects, written informed consent was obtained.

To establish serum lithium level at study entry, the 94 outpatients in the original study were initially treated for a baseline period of 2 months without changing their dose of lithium. During the baseline period, lithium was prescribed in capsules of the same appearance as those to be used in the randomization phase of the study so there would be no change in the appearance of the medication at the time of random assignment to treatment groups. After the patients were randomly assigned to a treatment group (0.4–0.6 meq/liter versus 0.8–1.0 meq/liter), a study physician who was not blinded to the subjects’ treatment group assignment adjusted each patient’s lithium dose to produce the designated serum lithium level. For patients with a prerandomization lithium level in the standard range who were assigned to the low lithium level group, the 300-mg lithium study capsules were replaced by identical 150-mg capsules, thus halving the dose while keeping the number of capsules constant.

Assignment was stratified and blocked at each treatment center on the basis of three clinical variables: length of remission since the last affective episode (less than 1 year versus 1 year or more), polarity of the last episode (mania versus depression), and number of prior episodes in the past 3 years (none, one, or two versus three or more).

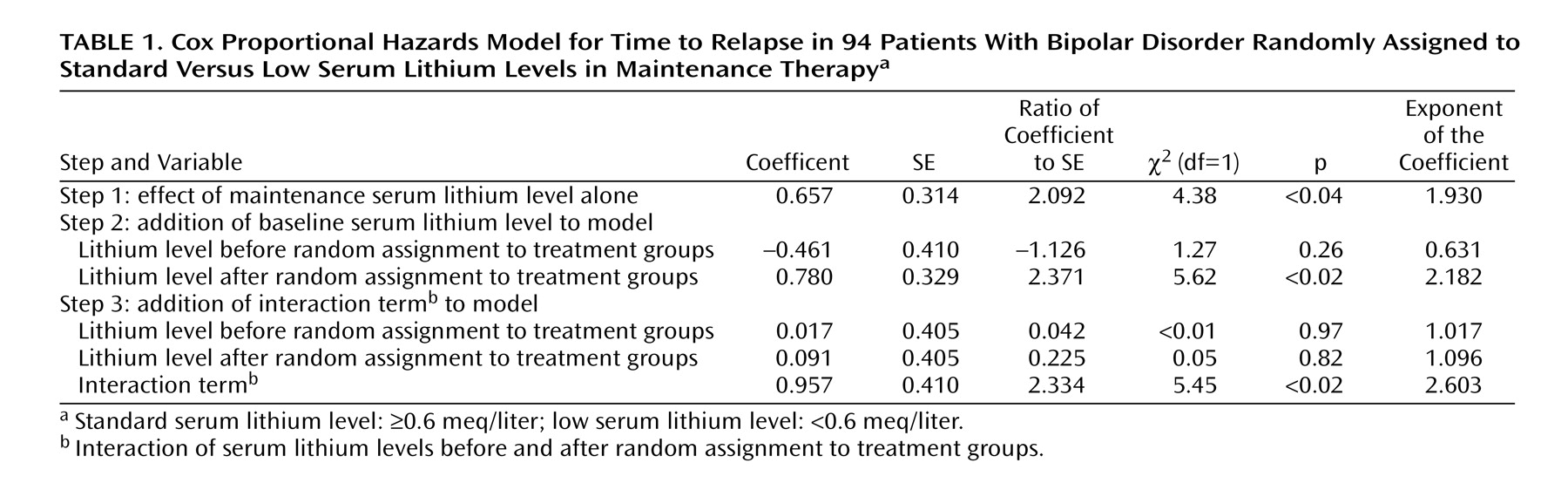

Reanalysis Method

In the original report, the potential influence of the change in dose status was not examined. To assess this potential confounding variable, we treated the prerandomization dose as if it were a stratification variable, defined as a low (producing a serum lithium level <0.6 meq/liter) or a standard (≥0.6 meq/liter) dose range. We used a Cox proportional hazards model to investigate the influence of the randomized treatment condition (low versus standard maintenance dose) relative to the main and interactive effects of prerandomization serum level. We also included the original stratification terms (length of remission, polarity of last episode, and number of episodes in the past 3 years) in this model as possible markers of recurrence risk.

In our outcome analysis, we used the same outcome criteria that were used in the original study: patients were defined as depressed or manic if they met either the appropriate DSM-III or the appropriate RDC criteria as assessed by clinicians blinded to treatment status. Hypomania in that study was defined as meeting RDC criteria for hypomania for 4 consecutive weeks, and occurrence of hypomania was also considered an endpoint. All analyses used an intent-to-treat design, with patients who did not relapse censored at the end of the follow-up period.

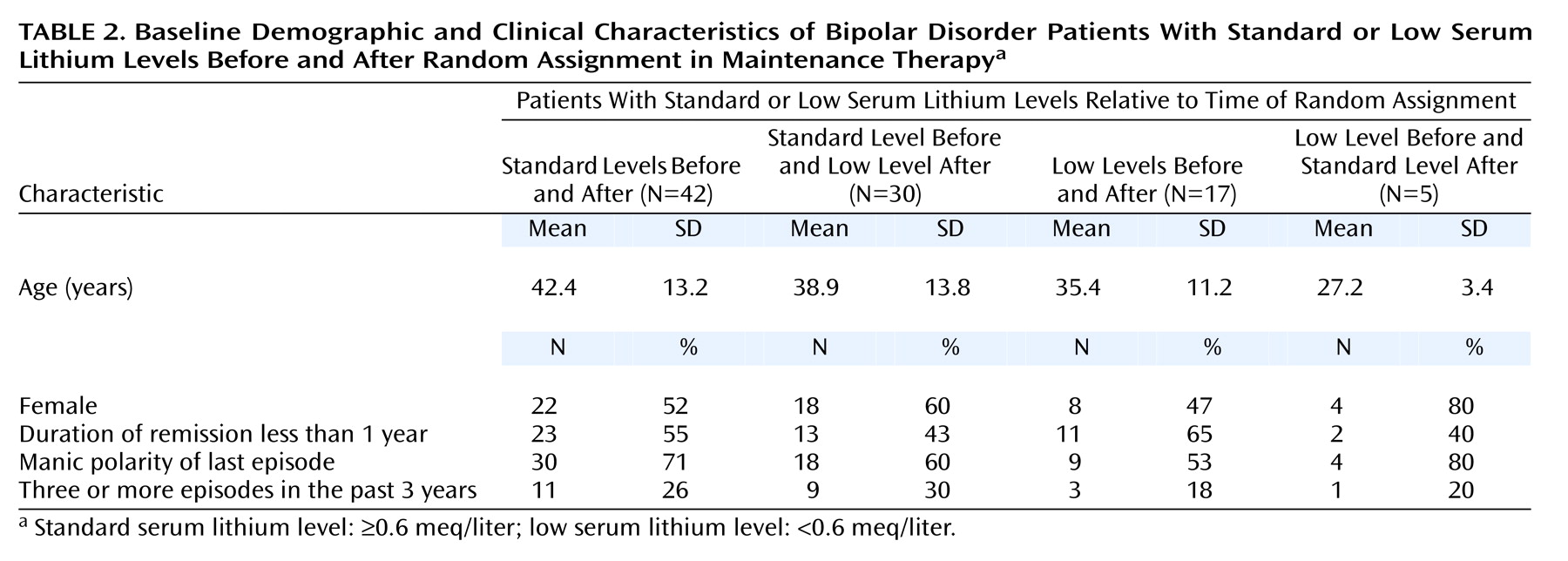

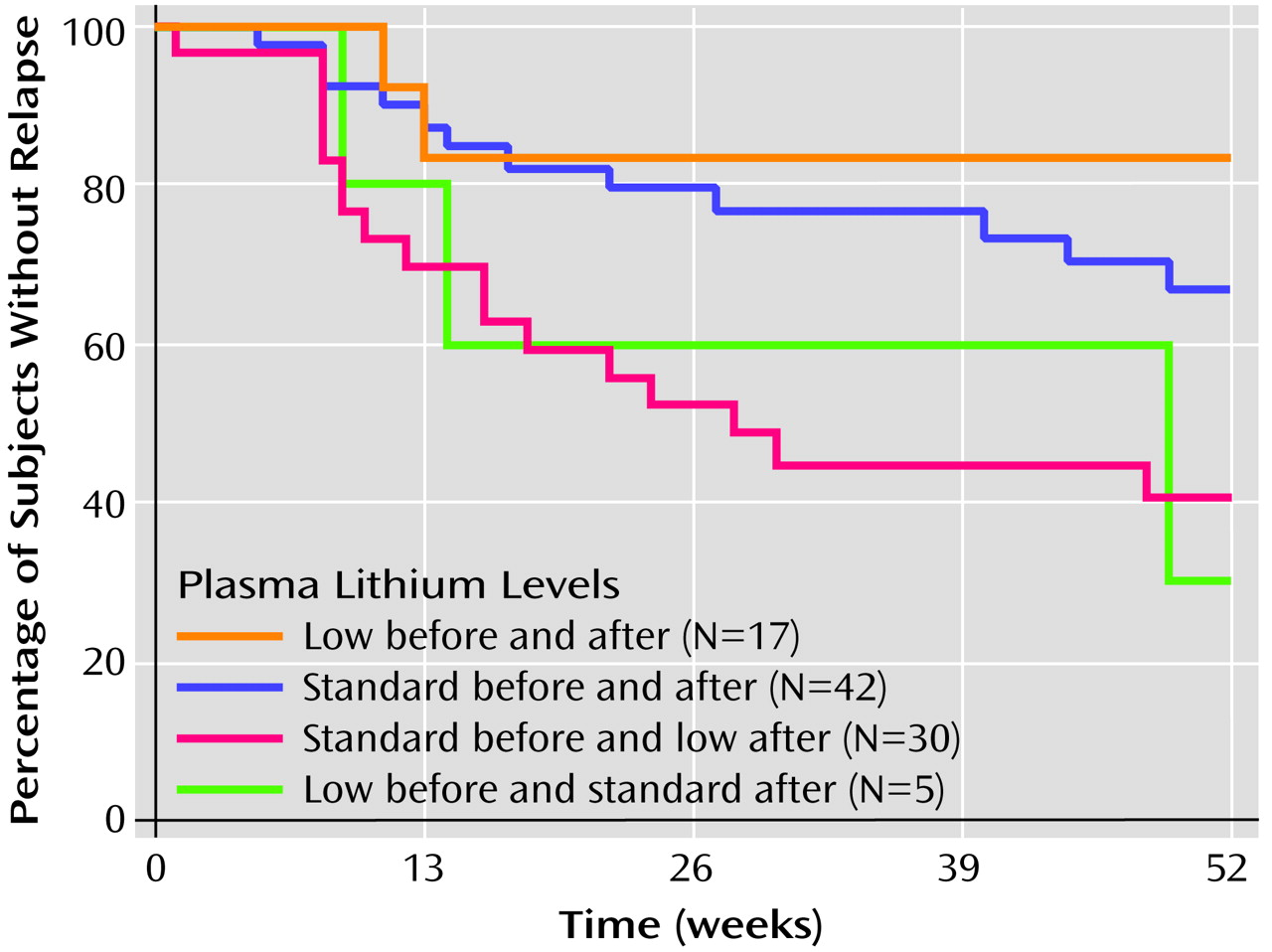

We subsequently illustrated the outcome of this analysis by presenting Kaplan-Meier survival curves for each of the following groups identified in relation to the point of random assignment:

1. Standard before and after: patients with prerandomization serum lithium levels in the standard range who were assigned to the standard range treatment group; at entry to the treatment phase, their lithium dose was not changed.

2. Standard before and low after: patients with prerandomization lithium levels in the standard range who were assigned to the low-range treatment group; at entry to treatment phase, their lithium dose was decreased.

3. Low before and after: patients with prerandomization serum lithium levels in the low range who were assigned to the low range treatment group; at entry to treatment phase, their lithium dose was not changed.

4. Low before and standard after: patients with prerandomization lithium levels in the low range who were assigned to the standard-range treatment group; at entry to treatment phase, their lithium dose was increased.

For this analysis, results from patients who did not relapse were censored at end of follow-up or after 52 weeks, whichever was less. This latter endpoint was selected because we believed that, given the substantial rates of discontinuation in the original study, survival curves would be unreliable beyond 1 year.

Survival curves were compared with the log-rank (Mantel-Cox) chi-square test. To better describe the four groups, baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of the groups were compared by using Kruskal-Wallis analysis of variance (ANOVA) for age and the Pearson chi-square test for all other variables. Statview for Windows, version 5.0 (SAS Institute, Cary, N.C.) was used for all analyses. All statistical tests were two-tailed, with significance set at p<0.05.

Discussion

In our reanalysis of the data from a prospective, randomized trial of lithium maintenance in bipolar disorder

(13), we found that the assigned dose of maintenance treatment appeared to have a dramatically different effect depending on whether this dose represented a change in treatment intensity. Patients whose lithium levels were abruptly decreased were more likely to suffer a recurrence than those whose levels were maintained in the same range as their prerandomization level. Indeed, when the change in dose level was taken into account in our reanalysis, the absolute level of maintenance therapy (low versus standard) was no longer a significant predictor of longitudinal outcome.

Our finding that a rapid decrease in serum lithium level may substantially increase the risk for episode recurrence is consistent with earlier studies

(2,

5) that have demonstrated a similar risk after abrupt lithium discontinuation. It also extends the findings of a small study in which patients with decreases in serum lithium level of greater than 0.2 meq/liter had a higher recurrence rate

(14).

The major limitation of this study is that it represents a post hoc analysis, addressing a question the original study was not designed to answer. Many factors in the original study, as well as our use of an intent-to-treat analysis, could bias our results towards the null hypothesis. For example, perhaps because of poorer compliance, lithium levels in the standard level group tended to deviate toward lower-than-target levels, which could obscure a true dose-response relationship. However, as it is unlikely that such a study could now be done prospectively for both ethical and logistical reasons, our results may represent the best opportunity to evaluate the consequences of abrupt dose change.

With these caveats in mind, a central implication of our findings is that conclusions about the negative effects of low maintenance doses in the Gelenberg et al. study may actually be specific to the change in dose level. It is possible that some lithium-treated patients may be safely maintained at lower serum lithium levels than standard guidelines would suggest. This interpretation is consistent with the results of several prospective maintenance trials

(15–

17) recently reviewed by Hopkins and Gelenberg

(18). In addition, in a crossover study that did discern a benefit of higher compared to lower lithium levels, many of the relapses occurred within 2 months after an abrupt decrease in lithium dose

(14). In our analysis, patients who continued to receive their original low dose of lithium did as well as patients who continued to receive their higher dose, although the small groups generated by our post hoc analysis yielded insufficient statistical power to detect a significant difference.

A complementary interpretation of these results is that greater baseline lithium level was a marker for greater disease severity, an example of confounding by indication. Patients came to their prerandomization lithium dose as a result of their personal history of treatment. However, it is noteworthy that we were unable to identify such differences in severity by examining three stratification variables from the original study: the number of prior episodes, duration of euthymia, and the polarity of the last episode. Moreover, statistical control of these severity variables in our proportional hazards models did not eliminate the interaction between pre- and postrandomization serum lithium levels on longitudinal outcome.

Even if it is not a marker of severity per se, serum lithium level at study entry could represent a marker for a given patient’s lithium requirement. A magnetic resonance spectroscopy study suggested only a weak correlation between serum lithium levels in the 0.6–1.0 meq/liter range and brain lithium levels

(19). This finding alone challenges the idea that high and low serum lithium levels may be adequate a priori for judging effective levels of the drug. Once an effective lithium dose has been established clinically for a particular patient, any change, not just abrupt change, could yield greater risk of recurrence.

Medication discontinuation strategies are relatively commonplace in studies of maintenance treatments of bipolar disorder

(20). Our study underscores the importance of considering current dose levels and taper effects, when examining the effects of maintenance treatments. In particular, we suggest that studies utilizing rapid discontinuation strategies may not provide an unambiguous accounting of treatment effects. For example, in many early placebo-controlled studies of the effects of lithium, lithium was abruptly discontinued on study entry

(21–

24), which may have artificially elevated the relapse rate in the placebo group, exaggerating the observed comparative benefit of lithium. As the optimum taper duration is unknown, even more recent studies in which lithium was tapered over 2 weeks

(20) may not represent true comparisons of treatment effects. Until the discontinuation effect is better characterized, we concur with the recommendations of Baldessarini et al.

(9) and Viguera et al.

(5) that lithium should be tapered over at least 2 weeks.

Our study was not able to answer questions about the effects of an abrupt increase in lithium dose for patients already receiving a low dose of medication. Only five patients underwent such a change, precluding confidence in the recurrence rates obtained for this cohort. Nonetheless, the relatively high recurrence rate we observed in this group bears watching in future studies where rapid dose escalation is used for otherwise stable patients.

The neurobiological mechanisms underlying the effects of rapid lithium dose change also merit further investigation. Lithium may yield both acute and chronic changes in central neurotransmission

(25,

26). In particular, adaptation to long-term lithium treatment may occur, rendering patients more vulnerable to fluctuations in lithium levels. One single photon emission computed tomography study

(27) of acute lithium withdrawal in stable euthymic bipolar disorder patients identified profound changes in perfusion: an increase in inferior posterior regions and a decrease in anterior cingulate cortex and other limbic areas. Similar studies after changes in lithium level may help to clarify the means by which recurrence risk is increased.

In summary, our study provides further evidence that abrupt decrease in lithium dose is associated with an elevated risk of recurrence in bipolar disorder. Past trials of lithium maintenance should be interpreted cautiously with this potential confounder in mind, and future trials should be designed to avoid or account for this effect.