Home care has grown into a vital source of health care, especially for older adults, who represent 72% of recipients

(1). Little is known about the mental health needs of these patients. In this article we report the distribution, correlates, and treatment status of DSM-IV major depression in a random sample of elderly patients receiving home health care for medical or surgical problems. Because major depression is associated in more healthy populations with significant risk for mortality, morbidity, institutionalization, and functional decline

(2–

8), investigating the extent to which depression affects home health care recipients represents an important step toward improving the clinical care and outcomes of this medically and functionally compromised patient population.

In the past two decades, use of home care services and the sector itself have grown rapidly. Between 1987 and 1997, Medicare’s spending for home care rose at an annual rate of 21%, and home care’s share of total Medicare expenditures increased from 2% to 9%

(11). During this time, the number of agencies certified by Medicare and the number of patients served annually doubled. In 1997, home health care cost Medicare $16.7 billion and served approximately 4 million Medicare enrollees, most of whom (85%) received skilled nursing care

(9–

11). Federal projections through 2008 estimate that the cost of home health care services will rise at a faster rate than the economy

(12). Factors fueling this rapid growth include increased size and longevity of the elderly population, shorter hospital stays, expansion of Medicare eligibility, and technological advances allowing delivery of more complex care in the home

(11).

This study is the first, to our knowledge, to investigate major depression among elderly recipients of home care nursing in the United States. Several investigators have reported high prevalence rates of depressive syndromes in elderly recipients of home-based health and social services in other countries

(13–

17). U.S. investigations have generally relied on convenience samples

(18–

20), chart diagnoses

(21), or symptom screens

(19,

20), which limit their utility for determining treatment needs

(2,

3).

High prevalence rates of current major depression have been reported in other medically ill or disabled elderly populations, including medical inpatients (11.5%–13.2%)

(22,

23) and nursing home residents (9.7%–12.6%)

(24–

26). These rates exceed those in elderly community samples (0.7%–1.4%)

(27–

29) and primary care patients (6.5%–9.0%)

(30,

31). On the basis of these data we expected that major depression would be highly common in home care patients and associated with greater medical morbidity, disability, and pain.

We also hypothesized that major depression in these patients would be largely undetected and untreated. Efficacious treatments for depression are available and can be effectively used in medically ill elderly patients

(3). In elderly primary care patients, however, depression goes undiagnosed more often than not, and, when diagnosed, is often inadequately treated

(32).

Method

This study received full review and approval from the Institutional Review Board of Weill Medical College of Cornell University. All patients included in the study provided signed informed consent.

Sample

The study drew a random sample of elderly patients newly admitted to the Visiting Nurse Services in Westchester, a traditional, not-for-profit certified home health agency serving a 450-square-mile county north of New York City. Visiting nurse services originated in the late 1800s and are now found throughout the United States

(11). Like many home health agencies, the collaborating agency employed social workers but no psychiatric nurses when these data were collected. Partially in response to its collaboration in this project, the agency has since opened a division of psychiatric home health care.

The study’s sampling strategy was designed to recruit a representative sample of agency patients admitted over a 2-year period (Dec. 1997 to Dec. 1999) who met the following criteria: 1) age 65 years old or older, 2) new admission, 3) able to give informed consent, and 4) able to speak English or Spanish. On a weekly basis, visiting nurse services admission data for each new patient were evaluated for potential study eligibility.

From the 3,416 potentially eligible patients, the study selected 40% at random (N=1,359); 470 patients (35%) were identified subsequently as ineligible. The primary reasons for ineligibility were termination from home care (by death, institutionalization, or recovery) and inability to give informed consent. Physicians and home health nurses were notified when their patients were sampled so they could notify the study if patients were inappropriate for study inclusion. The research associate fully explained the study aims and procedures to eligible patients, and 539 patients (61%) subsequently signed consent to participate.

Aggregate data provided by the agency indicated that, on average, participants were 2 years younger than patients who refused (mean age=78.4 years, SD=7.5, versus mean=80.2 years, SD=7.3) (t=3.58, df=885, p<0.001) but did not differ significantly by gender, nurse-reported mental status (e.g., disoriented, forgetful, depressed), prognosis, or ICD referring diagnosis

(33).

Participants were interviewed in their homes. With the patient’s permission, the study also obtained information about depression from an informant (informants were available for 355 patients [66%]). The majority of informants were spouses (N=144 [41%]) or adult children (N=131 [37%]). Patients with informant data did not differ from patients without informants in age, ethnicity, cognitive function, or functional status, but significantly more were men (χ

2=5.39, df=1, p<0.03), married (χ

2=35.1, df=1, p<0.0001), and living with children (χ

2=3.82, df=1, p<0.06), and they had significantly more comorbid medical diagnoses

(34) (mean=2.8, SD=2.1, versus mean=2.3, SD=1.9) (t=2.61, df=537, p<0.009).

Measures

Data reported in this paper come from the patient interview, informant interview, and visiting nurse services medical records (Health Care Financing Administration form 485).

To assess current and past history of depression, the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID)

(35) was given to patients and informants by research associates trained in its use. Interrater reliability in the assessment of SCID symptoms was evaluated by having a second research associate observe and independently rate symptoms during in-person interviews with 42 patients. Reliability was excellent (intraclass r=0.91, 95% confidence interval [CI]=0.86–0.95) for the number of symptoms present. Interviewer ratings were monitored throughout the study by the study psychologist (P.J.R.).

To protect patient confidentiality, research associates informed patients of symptoms consistent with a diagnosis of major depression and suggested they discuss these symptoms with their physician or home care nurse. In cases of high suicide risk, the research associates immediately notified the agency and physician, following a prescribed protocol.

A DSM-IV diagnosis of current major depression was determined by using consensus best-estimate conferences

(36,

37) that included the study’s geriatric psychiatrist (B.S.M.), geriatrician (D.J.K.), clinical psychologist (P.J.R.), and principal investigator (M.L.B.). The conference reviewed information from the patient SCID, informant SCID, and medical record data on medications and medical status. Case presentations protected the individual identity of the patient. Diagnoses of major depression followed DSM-IV’s “etiologic” approach, which excludes from diagnostic criteria symptoms judged solely attributable to general medical conditions or medications, a distinction that clinicians are able to judge reliably

(38).

The test-retest reliability of the consensus best-estimate process was evaluated approximately 6 months after the final patient follow-up interview. Thirty previously reviewed patients were randomly selected, stratified by depression severity, and reevaluated by the panel. Reliability for the three-level outcome of major, subthreshold, or no depression was excellent (weighted kappa=0.89, 95% CI=0.77–1.00).

Cognitive impairment was assessed by using the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE)

(39). Medical morbidity was determined from the medical record and patient interview by a geriatric internist (D.J.K.) using the Charlson Comorbidity Index

(34), excluding scores for psychiatric illness. This index takes into account both the number of illnesses and their severity by assigning different weights to each major category of disorder. The Charlson Comorbidity Index was originally created as a method for classifying medical comorbidity in order to predict mortality.

Disabilities in activities of daily living, instrumental activities of daily living, and mobility were measured by counts of activities that the patient was unable to do without assistance

(40). Pain intensity was assessed by the single three-level item from the Medical Outcomes Study 36-item Short-Form Health Survey

(41). Poverty status was estimated by using an algorithm that compared self-reported household income and family size with 1998 U.S. Department of Health and Human Services poverty guidelines

(42,

43).

Medication use was obtained from the medical record augmented by in-home review of medications. For antidepressants, dose adequacy was coded by using the Composite Antidepressant Treatment Intensity Scale

(44). Adherence to antidepressant medication was assessed by self-report; patients were classified as adherent if they used the medication as prescribed and forgot no more than 20% of weekly doses.

Statistical Analyses

Chi-square and t tests were used in bivariate analyses of major depression and sociodemographic, clinical, and functional factors. Logistic regression models estimated whether these factors were independently associated with major depression. Variables initially entered into the logistic model included age, gender, and variables whose bivariate relationship with depression was significant at p<0.25

(45). Likelihood ratio chi-square tests were computed to eliminate nonsignificant variables from the model by using a stepwise procedure. The final model included age, gender, and variables significant at p<0.10. Odds ratios were computed for the final model with 95% confidence intervals. All analyses were performed by using SAS software

(46), and tests of significance were two-tailed.

Results

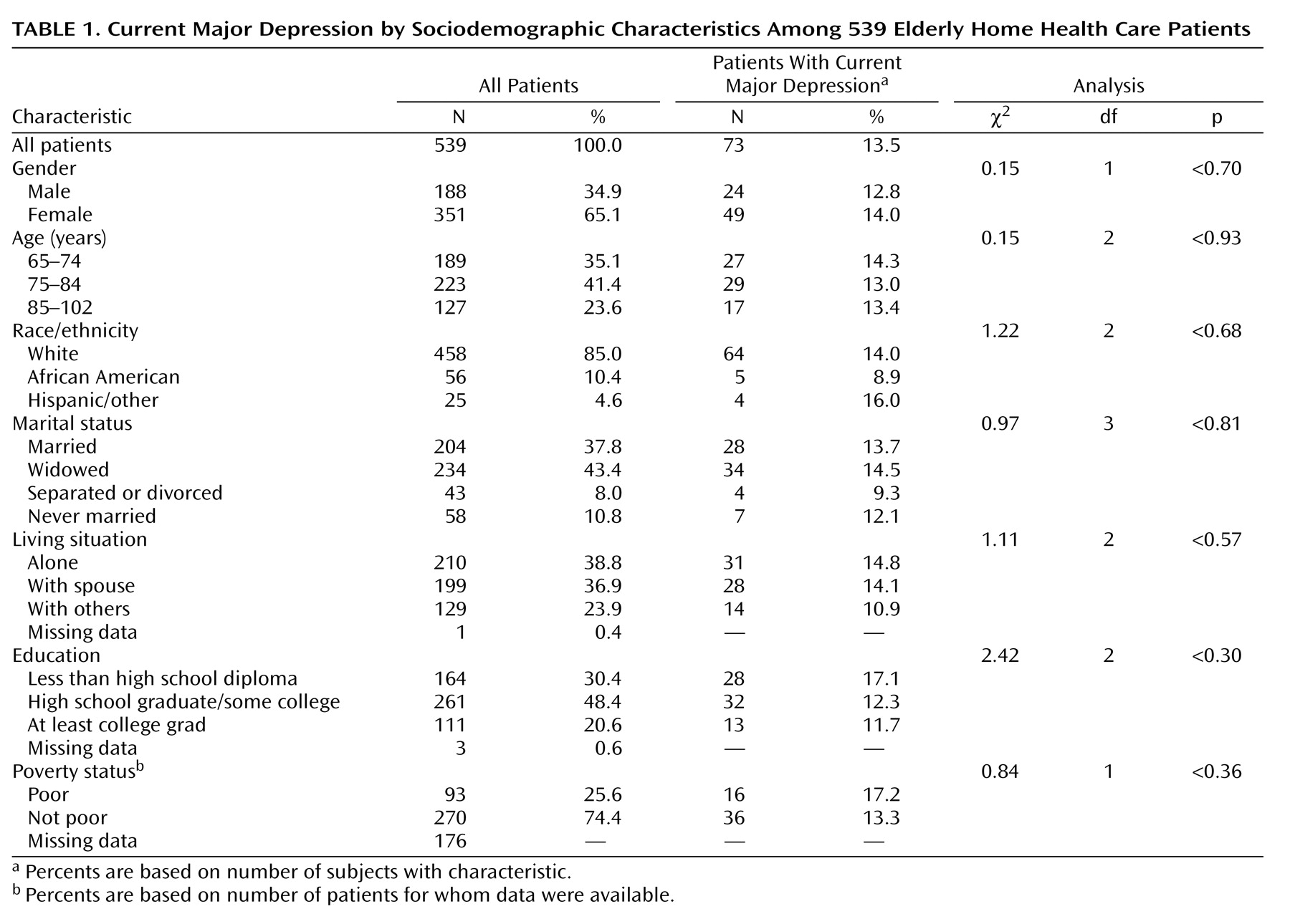

The demographic characteristics of the 539 patients (

Table 1) were similar to national statistics of home care patients

(1). Patients’ ages ranged from 65 to 102 years (mean=78.4, SD=7.5). The majority (65%) were female; 10% were African American, and 5% were Hispanic or other. Most patients lived alone (39%) or with a spouse (37%). Among the 363 patients with income data, 26% lived in poverty.

Most patients (N=347 [65% of the 534 patients for whom data were available]) began home care directly on hospital discharge; 121 (23%) were admitted after leaving nursing homes or rehabilitation facilities. The 539 patients had been referred by 359 different physicians.

Similar to home care patients nationally

(9), the most common referral diagnoses were circulatory diseases (N=164 [30%]), injuries (N=76 [14%]), and cancer (N=57 [11%]). Most patients had multiple medical conditions; the overall Charlson Comorbidity Index medical morbidity ranged from 0 to 10 (mean=2.7, SD=2.1). Ninety-six patients (18%) scored lower than 24 on the MMSE, indicating mild to severe cognitive impairment. More than half (N=289 [55% of the 527 patients for whom data were available]) reported at least one disability in activities of daily living (mean=1.1, SD=1.3, range=0–6). The sample averaged 3.3 disabilities in instrumental activities of daily living (SD=1.5, range=0–6) and 2.0 mobility restrictions (SD=1.0, range=0–3).

In comparison with the full population of elderly Medicare beneficiaries

(47), this sample of home care patients was older (24% versus 11% were 85 years old or older), disproportionately female (65% versus 57%), and more likely to live in poverty (26% versus 11%) but similar in racial/ethnic distribution. Compared with all Medicare beneficiaries, these home care patients were more than twice as likely to report at least one disability in activities of daily living (55% versus 23%).

According to DSM-IV criteria, 73 (13.5%) of the 539 patients (95% CI=10.8%–16.7%) were diagnosed with major depression. According to all available evidence, 52 (71%) of these 73 patients were classified as having their first episode of depression, although the accuracy of reported past history could not be determined and may be underestimated, as in other studies in late life

(48). Patients with reported new-onset depression were similar to those who had a previous episode on sociodemographic characteristics, medical comorbidity, and functional ability, but they were more likely to score below 24 on the MMSE (14 [27%] of 51 patients for whom MMSE data were available compared with one [5%] of 21) (Fisher’s exact test, p=0.05). In most cases (N=57 [N=78%]), the episode of depression had lasted at least 2 months (mean=13.3 months, SD=15.3, range=<1 to 60).

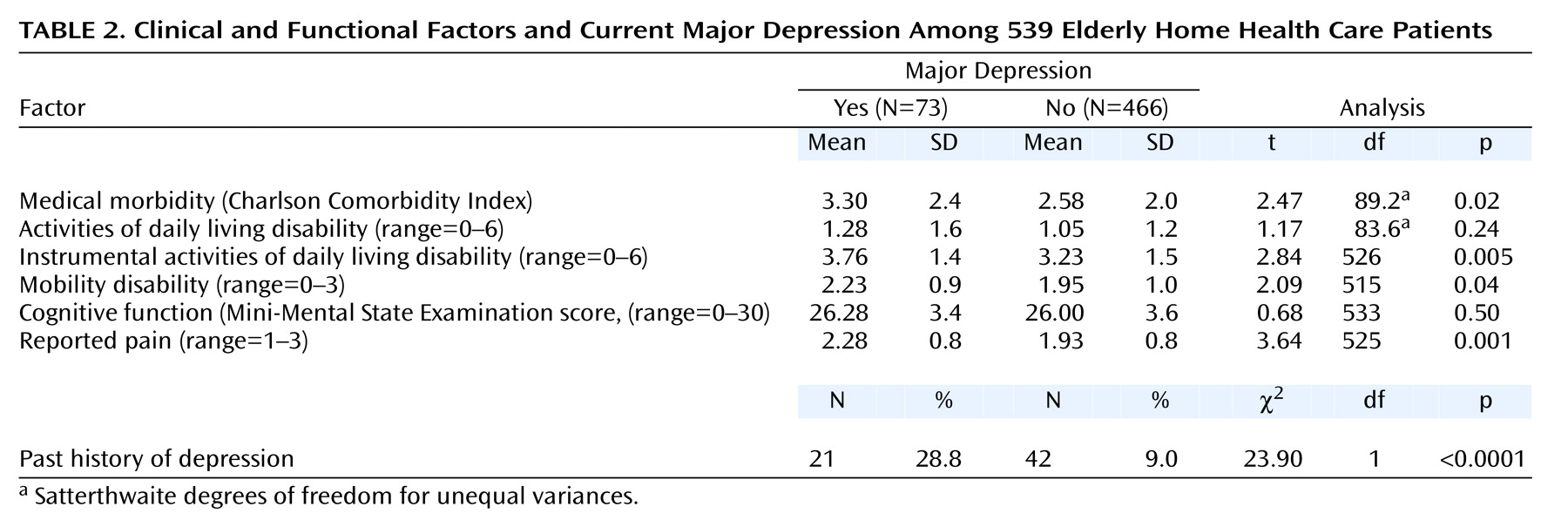

In bivariate analyses, major depression was not significantly associated with any sociodemographic factors (

Table 1) but was associated with greater medical morbidity, disability in instrumental activities of daily living, mobility disability, reported pain, and a past history of depression (

Table 2). The relationships of major depression with medical morbidity (adjusted odds ratio=1.13, 95% CI=1.01–1.27 per Charlson Comorbidity Index point, Wald χ

2=4.37, df=1, p<0.04), instrumental activities of daily living function (adjusted odds ratio=1.25, 95% CI=1.02–1.52, Wald χ

2=4.67, df=1, p<0.03), reported pain (adjusted odds ratio=1.82, 95% CI=1.27–2.62, Wald χ

2=10.64, df=1, p<0.001), and past history of depression (adjusted odds ratio=4.33, 95% CI=2.29–8.20, Wald χ

2=20.28, df=1, p<0.0001) remained significant in a multivariate logistic regression model controlling for age and gender. The relationship with mobility did not remain significant. Statistical interactions among these variables were tested, but none was significant.

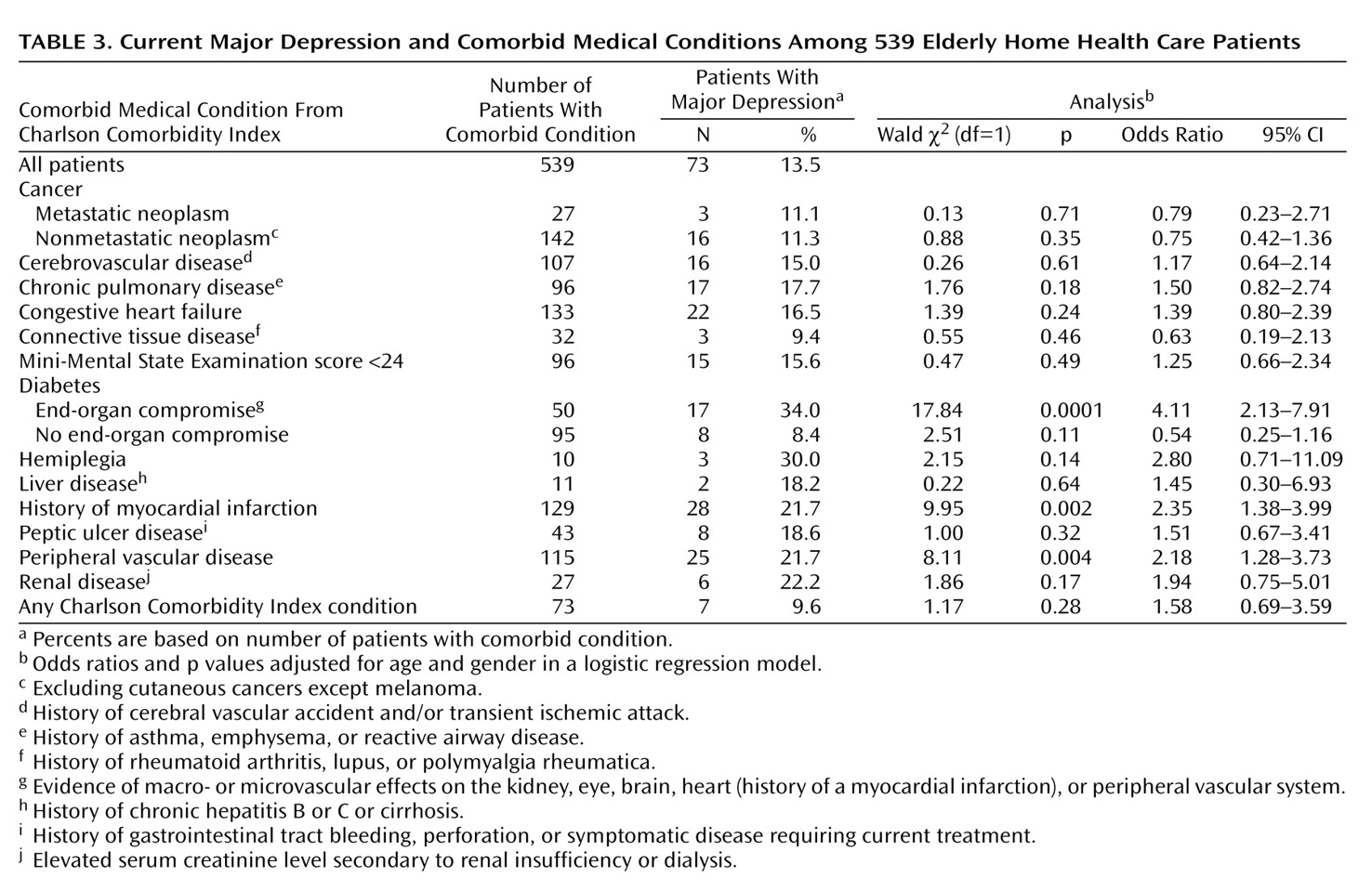

Consistent with the strong association between overall medical morbidity and major depression, three specific Charlson Comorbidity Index medical conditions had significantly higher rates of major depression when we controlled for age and gender (

Table 3): diabetes with end-organ compromise (adjusted odds ratio=4.11, 95% CI=2.13–7.91), history of myocardial infarction (adjusted odds ratio=2.35, 95% CI=1.38–3.99), and peripheral vascular disease (adjusted odds ratio=2.18, 95% CI=1.28–3.73). When statistical significance was set at p<0.004 to account for multiple comparisons

(49), all three conditions remained at least marginally significant (p<0.004). Several other medical conditions were positively associated with major depression but had limited statistical power.

Consistent with medical/surgical home care services, no patient had a psychiatric disorder listed as primary diagnosis on the home care medical record. Depression (ICD-9: 296.2, 296.3, 311.0) was a secondary diagnosis in 15 (3%) of the 539 patients, including two (3%) of the 73 patients with major depression.

Among the 73 depressed patients, 16 (22%) were receiving antidepressant treatment and none was receiving psychotherapy. Five (31%) of the 16 patients receiving antidepressants were prescribed subtherapeutic doses according to treatment guidelines

(50). Of the 11 patients prescribed appropriate doses, two (18%) reported not complying with their antidepressant treatment. According to these definitions, nine (12%) of 73 home care patients diagnosed with major depression were receiving adequate treatment.

Conclusions

This study’s primary finding is that 13.5% of newly admitted, geriatric home health care patients suffered from major depression. The majority of depressed patients (78%) were not receiving treatment for depression. Of those treated, a third had not been prescribed an appropriate dose according to accepted treatment guidelines.

In assessing major depression in elderly home care patients, the study hoped to determine the treatment needs of this large and growing patient population. Intensive diagnostic procedures were chosen to address the difficulties of accurately diagnosing depression in the elderly and medically ill. On the one hand, depression can be underestimated because many older adults minimize psychological symptoms and attribute sleep disturbances, fatigue, and other somatic symptoms of depression to physical health causes

(51,

52). On the other hand, the prevalence of major depression can be inflated in medically ill populations by misattributing symptoms of medical illness, medication side effects, or treatment sequelae to depression. Because we chose methods designed to minimize both potential sources of diagnostic measurement error, we believe that the estimated prevalence of major depression has clinical significance in this sample.

Is 13.5% a high rate of major depression? Research demonstrates that depression is both prevalent throughout the life span and costly in terms of individual suffering, negative sequelae, and health care utilization

(3). Embedded in this literature are debates on whether depression is better conceptualized and measured as a diagnosis or spectrum of symptoms

(53,

54) and whether diagnoses are more validly or reliability assessed by clinical judgment or self-report

(55–

57). We chose what might be considered the most conservative approach, using clinical judgment to make a strict DSM-IV diagnosis. Using similar criteria and procedures, Lyness et al.

(30) reported a prevalence of 6.5% in a representative sample of older primary care patients. The difference between that rate and the rate of 13.5% in our sample suggests that depression is twice as common in elderly home care patients.

In these patients, depression was usually first-onset, persistent, and associated with medical comorbidity, disability, and reported pain. These correlates have been implicated in both the risk and outcome of late life depression

(58,

59). These findings suggest that these complex and difficult-to-disentangle relationships persist even among patients suffering severe medical burden and disability. The specific associations with myocardial infarction, peripheral vascular disease, and diabetes are consistent with theories of vascular depression

(60). The sustained episodes suggest that depression was often more than a brief reaction to the events precipitating home care and may be associated with long-term declines in medical and functional status.

Factors that potentially limit the generalizability of these findings are sampling from a single agency and the 39% refusal rate. The agency is similar to visiting nurse services agencies throughout the United States, however, and the sample characteristics are similar to national norms

(9). The refusal rate reflects the challenges of conducting research with medically ill, frail patients in nonacademic settings and is consistent with other recent U.S. studies conducted in the homes of medically ill older adults

(61–

63). Patients who refused were surprisingly similar to participants.

Any attempt to characterize the needs of home care patients is challenged by the volatile home care environment. The Balanced Budget Act of 1997 restricted Medicare reimbursement for home health care in an effort to curb rising Medicare costs. Our sample was accrued during this period of constriction in Medicare spending. How these changes, as well as Medicare’s recently implemented home care prospective payment system, affect the needs and treatment options for older patients is not yet known.

Because major depression can be successfully treated in older patients

(3), our finding that depression is not only prevalent but mostly untreated in home health care patients is important for clinical practice. The complex configuration of home care presents a challenge to identifying depression in these patients. Physicians have little opportunity for directly assessing their home health care patients, unlike the patients they see in primary care. The visiting nurse generally serves as the eyes and ears of the physician, thereby playing a key role in establishing the presence of depression and potential need for treatment.

Depressive symptoms are an accepted component of a comprehensive geriatric assessment

(64,

65), and nurses are now expected to assess depressive symptoms as part of the Health Care Financing Administration’s mandatory use, collection, encoding, and transmission of outcome and assessment set

(66). However, home health nurses typically are not trained in the assessment of depression or in diagnostic criteria

(67), limiting the usefulness of their observations for making treatment decisions

(68). This study found that over 40% of the depressed patients receiving antidepressant therapy received inadequate treatment either because the prescribed dose was below recommended guidelines or the patient was noncompliant. Accordingly, home care strategies are needed to improve treatment initiation and management as well as case identification. The challenge is to improve depression care in the context of the complex organization of the nurse-physician-patient triad, the increasing time and financial pressures faced by both home care agencies and physicians, and patient frailty.

Effective strategies will likely draw from three areas of research. First are primary care interventions to improve treatment of geriatric depression through the use of structured treatment guidelines and care managers

(32,

69). Second are comprehensive home-based interventions that target the full range of nursing and psychosocial needs in geriatric patients

(62,

63,

70). Third are “telemedicine” strategies to facilitate clinical care for hard-to-reach populations, such as the rural and homebound

(71).

The immediate goal of any depression intervention in home health care is recovery from depression and reduction of depressive symptoms. Data from other populations suggest that treating depression may reduce the risk of negative functional outcomes as well. Functional outcomes are especially important in home health care, both because good functional status is critical in allowing older adults to remain in their own homes and because Medicare’s prospective payment system bases reimbursement on functional outcomes. Despite the availability of efficacious treatments for depression, however, only nine (12%) of our depressed home care patients received adequate antidepressant treatment. This magnitude of untreated major depression underscores the critical need for effective strategies to reduce the burden of depression in older home health care patients.