Progression of Subcortical Ischemic Disease From Vascular Depression to Vascular Dementia

Case Report

Ms. A was a 78-year-old widowed white woman whose daughters brought her to our mood disorders clinic for evaluation of recurrent major depression.

History

Ms. A’s chief complaint was “I don’t feel like doing anything anymore.” Over the previous 6 months, Ms. A had become increasingly depressed, dependent on her daughters, and more physically frail. She was not motivated to perform her usual activities. She reported a depressed mood, frequent crying spells, poor sleep, with trouble falling asleep, as well as frequent awakenings during the night, a low energy level, and difficulty concentrating. She reported no suicidal ideation or psychotic symptoms. She was taking paroxetine, 20 mg/day, at the time of her initial evaluation.Ms. A had a history of depression dating back approximately 13 years, which occurred in the context of marital discord and “a spell” that was later diagnosed as a left internal capsule lacunar infarct. During the course of that episode, she had failed to respond to several medications and ultimately received a course of 14 sessions of ECT, to which she responded well. Her mood had been maintained with antidepressant medications, most recently sertraline, until 3 years previously, when her husband died. At that time, she developed a recurrence of depressive symptoms, along with a decreased capacity for self-care; this impairment was so significant that her daughters placed her in an assisted-living facility so that her needs could be better met. Her psychiatrist changed her medications to a combination of trimipramine and sertraline. One year later, or 2 years before Ms. A was seen for treatment, she had experienced a recurrence of severe depressive symptoms, was admitted to the hospital, and received a course of eight ECT treatments. She was given paroxetine, 20 mg at bedtime, which she continued to take over the next 2 years. During that hospitalization, a brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan revealed moderately severe subcortical white matter disease.Ms. A’s medical history was significant for hypercholesterolemia, gastritis, gouty arthritis, and osteoporosis. Her medications included 40 mg of simvastatin at bedtime, 20 mg of paroxetine at bedtime, 300 mg b.i.d. of allopurinol, 150 mg b.i.d. of ranitidine, 0.625 mg/day of conjugated estrogen, and 500 mg/day of a calcium supplement.Ms. A’s social history revealed that she was the youngest of four children. Her father had a stroke when she was 13; Ms. A cared for him until she her early 20s, when she married. She and her husband were married for 49 years and raised two daughters. She completed high school but never had regular employment outside of the home, and she never learned to drive.Ms. A’s daughters noted that after their father died, “Mother fell apart.” They thought that the paroxetine had helped improve her depression to some extent, particularly her ability to manage her household affairs. However, they stated that she had “never been the same” since their father’s death.A mental status examination revealed a melancholy older woman with little spontaneous movement. Her speech pattern had a low tone and a high latency. She generally had a flat affect but was sporadically tearful during the interview. She described her mood as “low.” Her psychomotor activity was diminished, and her thought processes were goal directed. She reported poor concentration. She reported no psychotic symptoms or suicidal or homicidal ideation. She scored 28 of 30 on the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) (1); she incorrectly answered one question regarding the country she lived in and missed one question by spelling “world” backward.Ms. A’s daughters brought her most recent results from laboratory testing from her general practitioner. They included normal results for blood chemistries, a CBC, and a thyroid profile, including levels of thyroid-stimulating hormone, vitamin B12, and folate.

Initial Treatment Plan

At her initial evaluation, Ms. A was diagnosed with recurrent severe major depression. She agreed to enroll in our mental health clinical research center, through which she received a cranial MRI scan. The initial plan was to taper her off paroxetine and initiate treatment with sertraline at a dose of 25 mg/day. In addition, Ms. A and her daughters were instructed to work with the assisted-living facility’s activities staff to identify pleasurable activities in which Ms. A could gradually increase her involvement.

Course of Treatment

Year 1

Over the next 3 months, Ms. A switched from paroxetine to sertraline, which was increased to 50 mg/day. She continued to experience depressive symptoms, so during the ensuing 6 months, her sertraline dose was further titrated to 100 mg/day. At this dose, she noted an improvement in her sleep and appetite. Her mood appeared brighter. However, she continued to experience little interest in activities, a diminished ability to experience pleasure in activities going on at the assisted-living facility, and low energy levels. At this point, sustained-release bupropion, 100 mg/day, was added to her sertraline dose.Over the ensuing 2 to 3 months, halfway through her first year of treatment, Ms. A had mild improvement in both her mood and apathy symptoms. At her 9-month visit, she began to experience some weakness and shortness of breath when walking. She was diagnosed with congestive heart failure. Both long-acting diltiazem and digoxin were added to her medication regimen. Rather than changing her antidepressant medications, the decision was made to monitor her progress with sertraline and sustained-release bupropion while her medical problems were being treated.

Year 2

Six months later, at her 15-month visit, Ms. A’s daughters were concerned that she continued to spend much of her time in bed and refused to pursue activities suggested by her assisted-living facility. They also reported that she was confused at times during the day. They had taken her to her general practitioner, who could not find any acute medical problem to explain her symptoms. Upon examination, she reported a full range of depression symptoms and had an MMSE score of 16. Another course of ECT sessions was discussed, but Ms. A was not interested. Instead, at this time, the decision was made to taper her off the sertraline, discontinue the bupropion, and initiate extended-release venlafaxine. She started taking a dose of 37.5 mg/day of venlafaxine, and over the ensuing 2 weeks, her dose was increased to 75 mg/day.Six weeks later, one of Ms. A’s daughters called the treating psychiatrist and reported, “Mother is a new woman.” Ms. A had begun to participate more in activities and was more interested in what was going on at the assisted-living facility and with her family. At her 18-month visit, Ms. A appeared in a brighter mood and reported no depressive symptoms. Despite this improvement in her depressive symptoms, during the interview, Ms. A had difficulty processing information. Her MMSE score was 21; she had errors regarding the year, the date, the day of the week, the month, the country, and the floor of building, spelled “world” in a convoluted manner (“DLROE”), recalled only one of three items, and had difficulty placing a sheet of paper on her lap.

Years 3 and 4

At Ms. A’s 24-month visit, her depression remained stable while she was taking extended-release venlafaxine. Her daughters noticed that she continued to be confused at times, with ongoing difficulties in keeping up with what was going on in the family. She did not comprehend everything that people were saying, which she blamed on poor hearing. Her treating psychiatrist maintained her status with extended-release venlafaxine and initiated donepezil, 5 mg at bedtime. Her dose was increased to 10 mg at bedtime 12 weeks later.Six months later, Ms. A continued to be in remission of her depressive symptoms. In the interim, her general practitioner had noted her cognitive impairment and had initiated a course of monthly vitamin B12 injections. After 4 years of follow-up, Ms. A continued to do well in terms of her depressive symptoms. Her daughters noted an improved awareness of what was going on around her. Her MMSE score was 25, with errors regarding orientation and in following a three-step command.

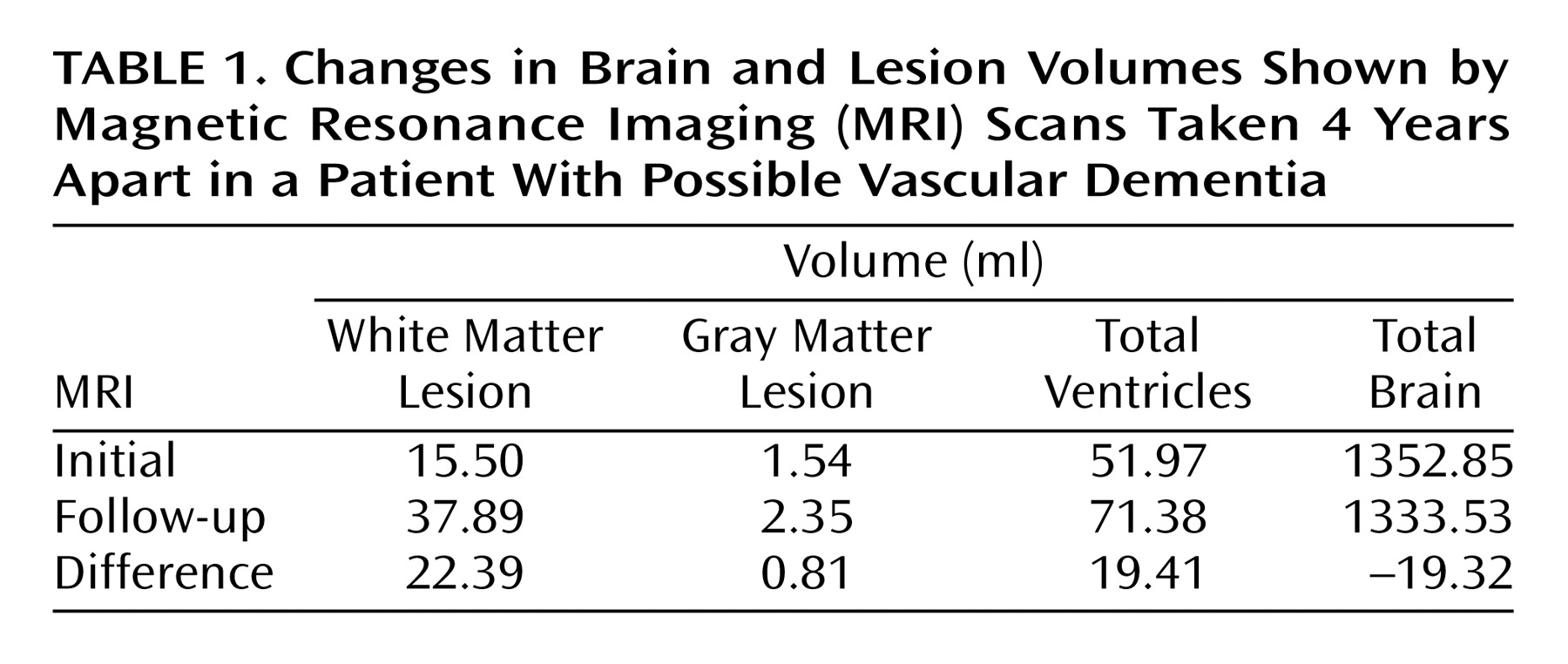

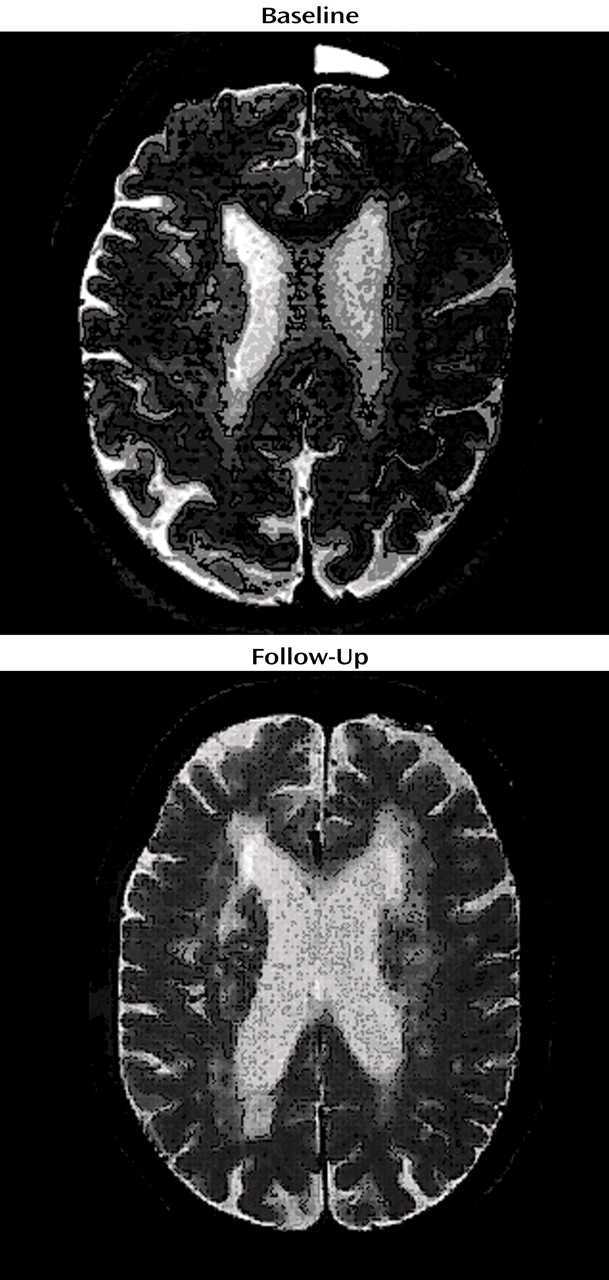

Changes in Ms. A’s Cranial MRI

Because of her participation in the clinical research study, Ms. A received an initial cranial MRI, then another MRI 4 years later (Figure 1). A semiautomated segmentation method (2) was used to measure total brain, ventricle, and lesion volumes. Ms. A demonstrated a striking increase in both gray and white matter lesion volumes over this period, while maintaining a relatively constant total brain volume (Table 1).

Discussion

Vascular Disease and Depression

Antidepressant Therapy and Medical Illness in the Elderly

Depression and Cognitive Impairment

Conclusions: The Vascular Depression Hypothesis

Footnote

References

Information & Authors

Information

Published In

History

Authors

Metrics & Citations

Metrics

Citations

Export Citations

If you have the appropriate software installed, you can download article citation data to the citation manager of your choice. Simply select your manager software from the list below and click Download.

For more information or tips please see 'Downloading to a citation manager' in the Help menu.

View Options

View options

PDF/EPUB

View PDF/EPUBGet Access

Login options

Already a subscriber? Access your subscription through your login credentials or your institution for full access to this article.

Personal login Institutional Login Open Athens loginNot a subscriber?

PsychiatryOnline subscription options offer access to the DSM-5-TR® library, books, journals, CME, and patient resources. This all-in-one virtual library provides psychiatrists and mental health professionals with key resources for diagnosis, treatment, research, and professional development.

Need more help? PsychiatryOnline Customer Service may be reached by emailing [email protected] or by calling 800-368-5777 (in the U.S.) or 703-907-7322 (outside the U.S.).