Depression in nursing home patients has been associated with subnutrition, behavioral problems, noncompliance with treatment, increased nursing staff time, and excessive mortality rates, especially among those with dementia

(1). Estimates of the prevalence of major and minor depression among nursing home residents range from 6% to 24% and 30% to 50%, respectively

(1). Among individuals with dementia, rates of all types of depression range from 14% to 39%

(2,

3).

Various studies conducted in the 1990s found that fewer than one-fourth of depressed patients were identified and treated by nursing home physicians

(1–

4). More recent studies suggest that treatment rates may be increasing, but patients often receive suboptimal levels of antidepressant medications

(5). Given the evidence that depression is frequently overlooked and undertreated, it is desirable to develop strategies for its recognition and treatment among dementia patients. One study found that a weekly educational course produced only a small increase in knowledge about depression, but the authors concluded that the identification and treatment of depression had not been altered appreciably

(6). Moreover, weekly staff educational meetings can pose financial and logistical difficulties for many nursing homes.

Alternatively, on the basis of a small pilot project, we hypothesized that mandatory depression screening might be an effective and easily implemented method for augmenting the recognition and treatment of depression among nursing home patients with dementia. In this approach, once patients exceeded a cutoff score on a screening instrument, they would be referred for a psychiatric evaluation. In theory, the Minimum Data Set, a quarterly assessment of residents that is mandated by government regulations, should serve this screening function. However, we found previously that the Minimum Data Set missed 75% of major depressive disorders and 87% of all types of depression

(7,

8), and among those identified by the Minimum Data Set as depressed, only 33% received an antidepressant medication.

This study addresses the following questions with respect to the process, outcome, and impact of instituting a mandatory depression screening program in two nursing homes:

Results

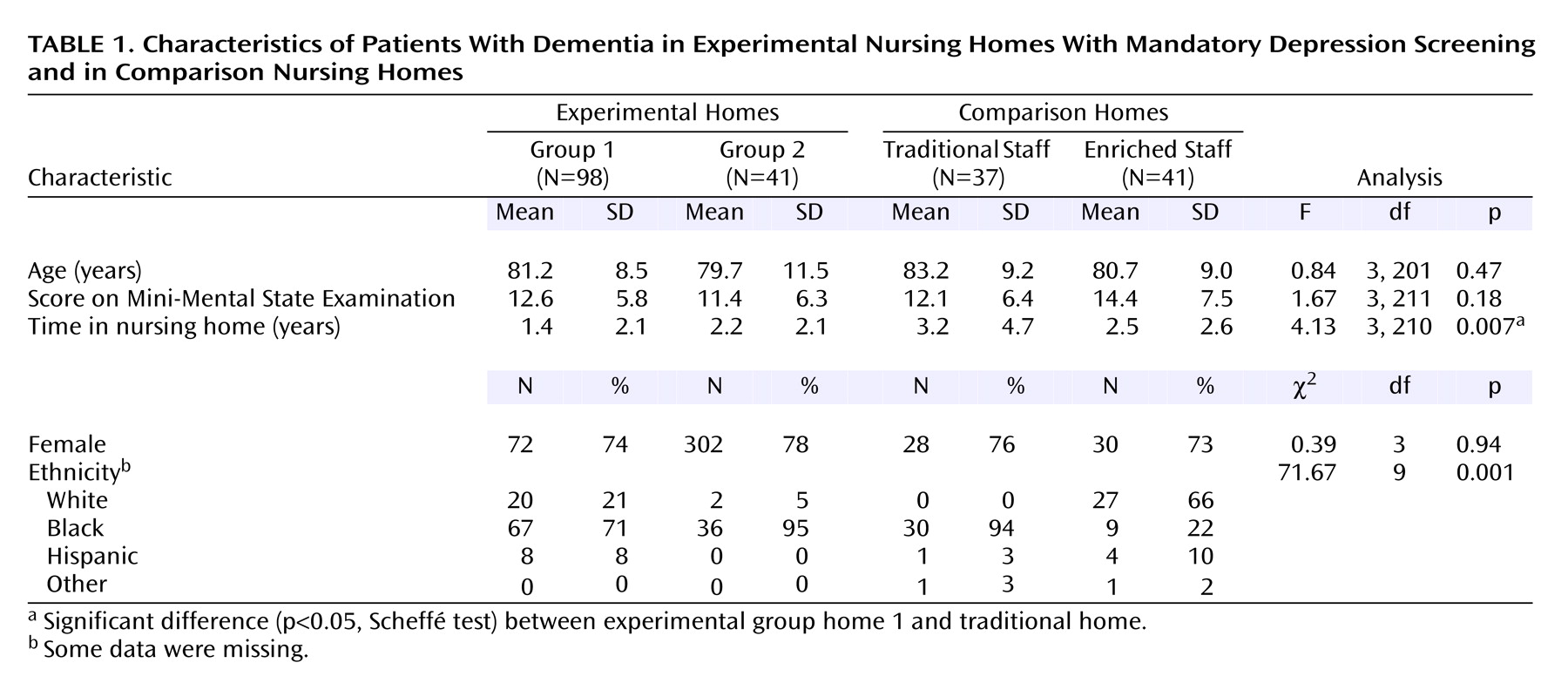

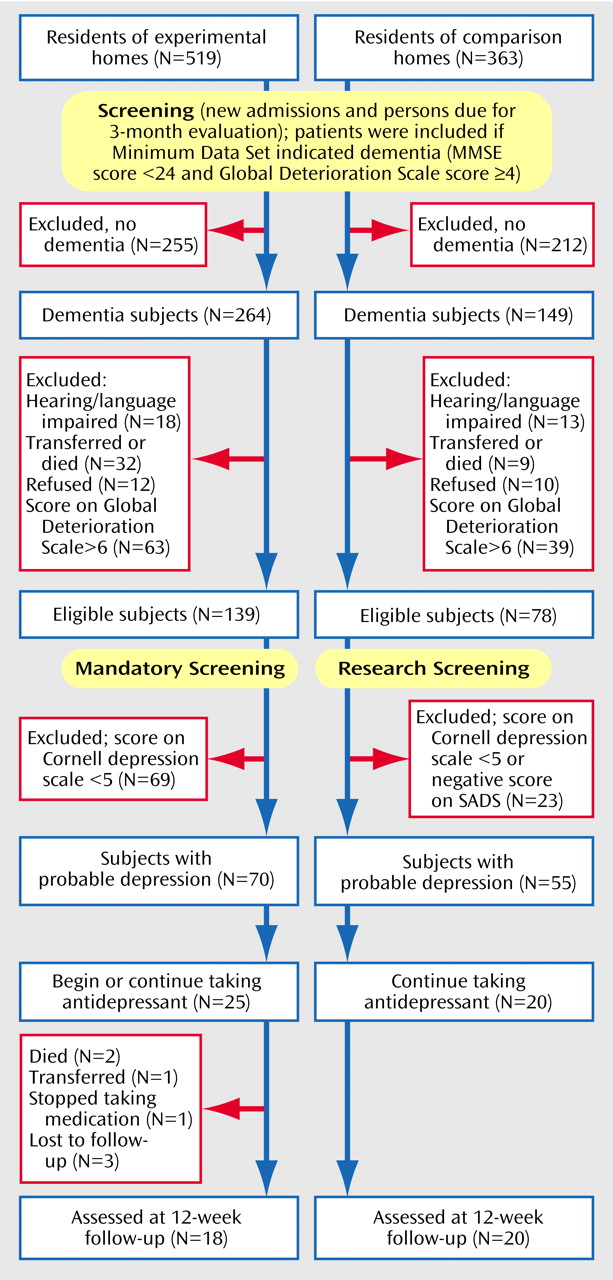

As shown in

Table 1, there were no significant differences in age, MMSE score, and gender among the eligible subjects in the experimental group and the comparison group. However, the eligible subjects in the experimental group had shorter lengths of stays; the difference between experimental group home 1 and the “typical” comparison group home was statistically significant. There were also significant differences in ethnic distribution; the “enriched” comparison group home had appreciably more Caucasian residents than the other homes. As noted in

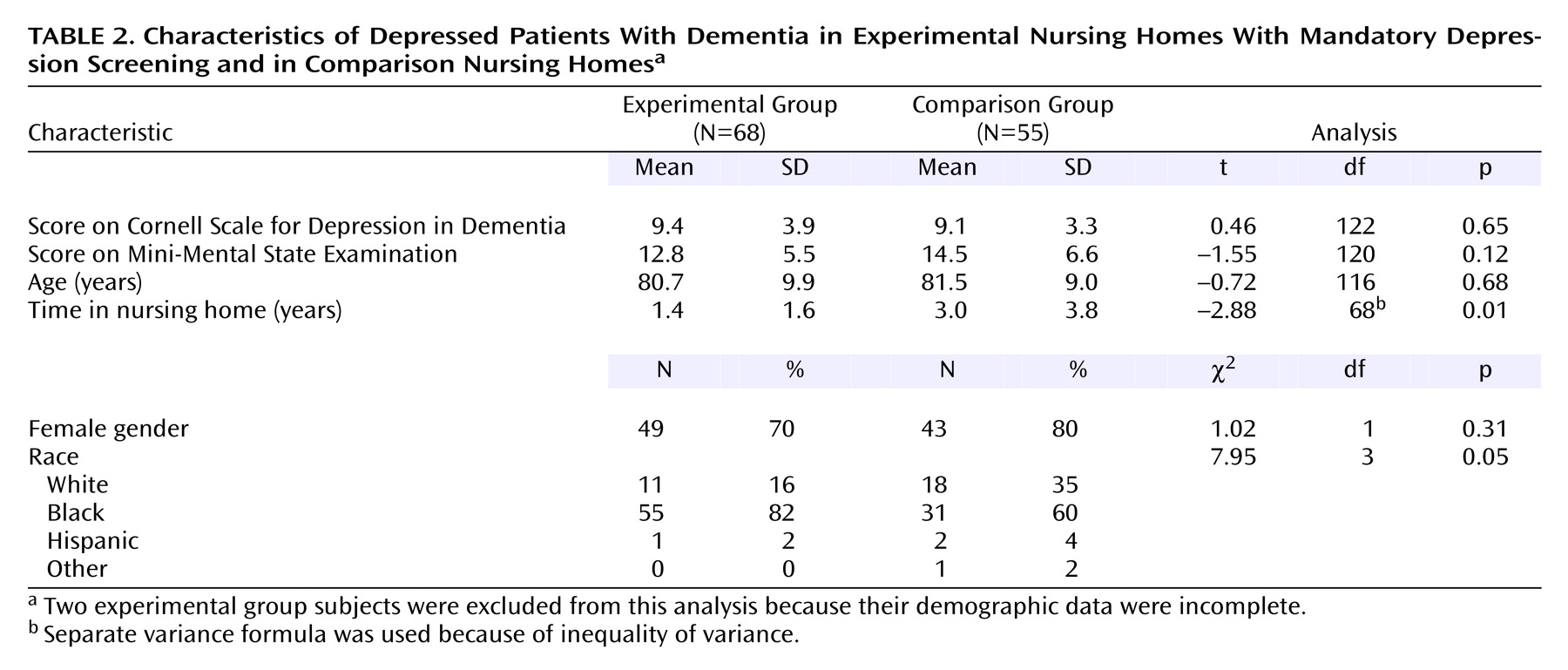

Table 2, among the eligible subjects who were found to be depressed based on the Cornell scale screening (and confirmation with the SADS in the comparison group), there were no significant differences in Cornell scale scores, MMSE score, age, and gender; however, the residents in the experimental group had significantly shorter lengths of stay and were proportionately more nonwhite. Thus, the differences between nursing home groups in the depressed state were similar to the group differences in the eligible pool of dementia patients.

Mandatory screening had a significant effect on the two experimental group homes. We found that before screening, only 16% of the patients with Cornell scale scores ≥5 were given prescriptions for antidepressant medication, whereas after the screening procedures were introduced, 36% of these patients were given prescriptions for antidepressants (χ2=20.29, df=1, p<0.001, McNemar test). Similarly, for patients with more severe depression (Cornell scale score ≥8), 20% and 44% were prescribed medication pre- and postscreening, respectively (χ2=11.39, df=1, p<0.001, McNemar test).

There were no differences in the number of patients given prescriptions for antidepressants in the experimental group postintervention (36%) and the comparison group (37%) (χ2=0.00, df=1, p=1.00). However, on more detailed analysis, we found that in the “traditional” comparison group, only 19% of all patients with Cornell scale scores ≥5 received antidepressants, although this was not significantly different from the experimental group postintervention (χ2=1.07, df=1, p=0.30). Among the more severely depressed patients (Cornell scale score ≥8) in the “traditional” comparison group, 23% were receiving antidepressants, which was nearly one-half the level of the experimental group postintervention, although this difference was also not significant (χ2=1.14, df=1, p=0.29). On the other hand, in the “enriched” comparison group, 52% of the individuals with Cornell scale scores of ≥5 were given antidepressants, and 65% of the patients with Cornell scale scores of ≥8 were given antidepressants. Neither of these percentages were statistically different from the experimental group (for Cornell scale scores ≥5, χ2=1.49, df=1, p=0.22; for Cornell scale scores ≥8: χ2=1.59, df=1, p=0.21).

In looking at both groups postintervention, the use of antidepressant medication was significantly associated with scores on the Cornell scale (r=0.32, p=<0.001), being Caucasian (r=0.31, p=<0.001), and higher MMSE scores (r=0.24, p=<0.01), whereas health, score on the Activities of Daily Living Scale, score on the Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale for neuropsychiatric symptoms, gender, and time in the nursing home were not significantly associated with receiving antidepressant treatment. After adding control for Cornell scale and MMSE scores, being Caucasian was still significantly correlated with receiving treatment (r=0.25, p<0.01); this association was significant (r=0.40, p<0.001) even when the analysis was restricted to the two experimental group homes and the one comparison group home that had predominantly non-Caucasian residents. Of note, in the experimental group, after we instituted mandatory screening, there was a significant increase in the proportion of depressed nonwhites receiving antidepressants (9% versus 27%) (χ2=11.19, df=1, p=0.002, McNemar test).

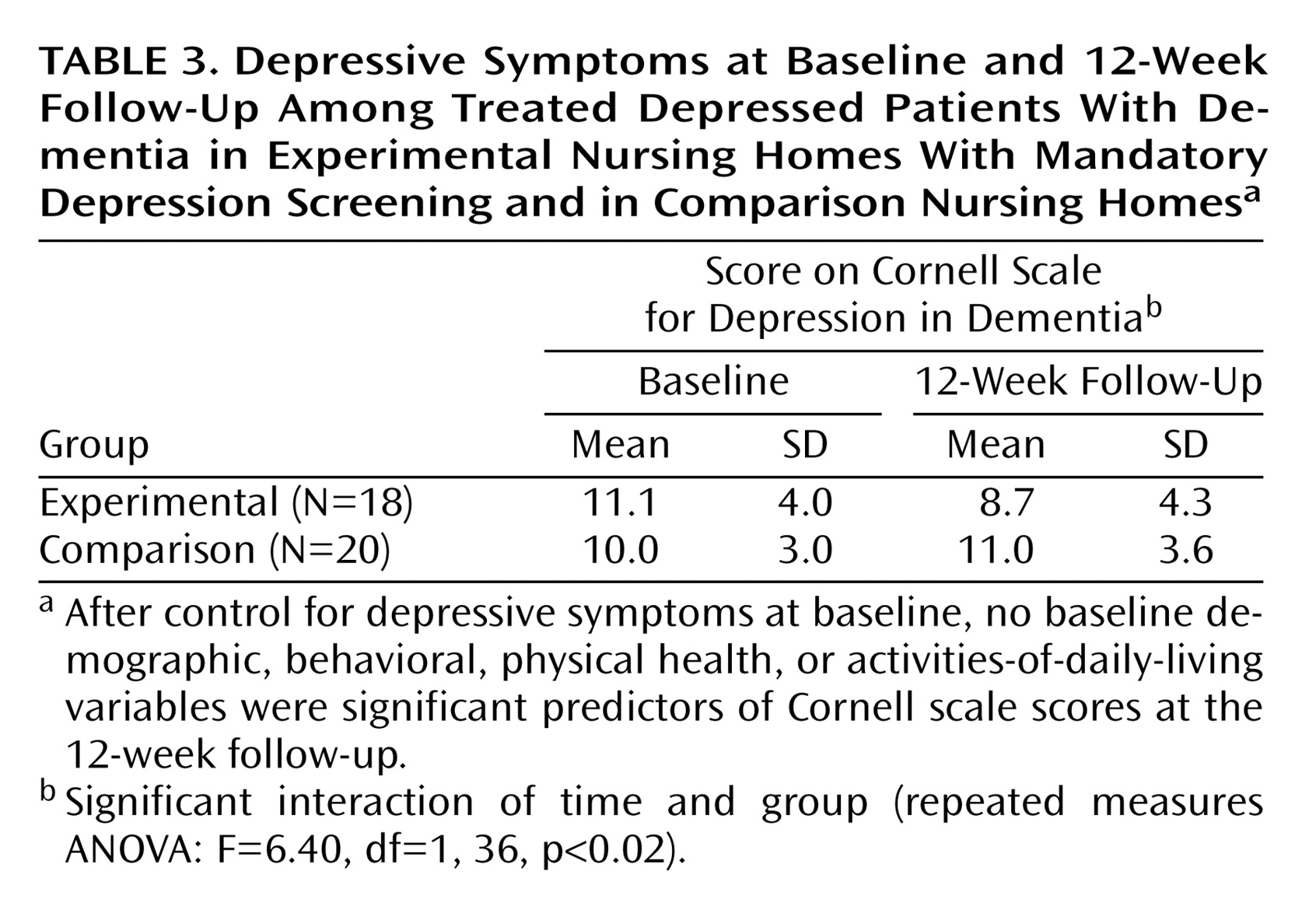

Using a repeated-measures ANOVA, we contrasted depressed patients in the experimental group and the comparison group who were receiving antidepressant medication. At the 12-week follow-up, there were significant differences between the two groups; the experimental group showed a 22% decline and the comparison group a 9% increase in Cornell scale scores (

Table 3). Among the more severely depressed patients (Cornell scale score ≥8), the experimental group likewise had a significantly better outcome than the comparison group (a 24% decline versus 4% increase) (F=5.44, df=1, 29, p=0.03). Within the experimental group, there was no significant difference in the reduction in Cornell scale scores between the patients already taking antidepressants and those given antidepressants after mandatory screening (F=0.25, df=1, 16, p=0.63). Finally there was a significant difference in the percentage of patients in the experimental group (28%) and those in the comparison group (0%), who showed at least a 50% decline in depressive symptoms (χ

2=4.20, df=1, p=0.04).

Discussion

The findings have important implications for clinical care and public policy. First, with respect to process evaluation, we demonstrated that clinical staff can easily use the Cornell scale and that referrals based on a cutoff score of ≥5 did not place an undue burden on staff psychiatrists (i.e., 100% of patients who scored ≥5 on the Cornell scale were evaluated by psychiatrists).

Second, with respect to outcome evaluation, we showed that depression screening resulted in significantly more depressed dementia patients receiving antidepressants in the experimental nursing homes, although it was somewhat disappointing that only 44% of the more severely depressed patients were given antidepressants. This may in part reflect the fact that depression was sometimes accompanied by agitation and other neuropsychiatric symptoms, thereby resulting in the prescription of other classes of psychotropic medications.

Our choice of using one comparison home that was more staff enriched than the experimental homes or the other comparison home attenuated the overall differences between the experimental and comparison groups. Nevertheless, it afforded an opportunity to contrast our intervention with different types of settings and staffing. The percentage of patients receiving antidepressants in the experimental group (postintervention) exceeded that of the “traditional” comparison group, whereas the percentage of patients receiving antidepressants in the “staff-enriched” comparison group was greater than that of the experimental group, although none of these differences were statistically significant. While the current study group had sufficient power to detect “medium” size effects between groups

(14), a larger group would have been able to detect smaller effects that might have revealed significant group differences. Of importance, our data indicated that a psychologically enriched staff who are sensitized to recognize and treat depression, as well as being able to communicate the importance of the recognition of depression to nonpsychologically-trained staff, can generate a high level of treatment. Unfortunately, most nursing homes cannot afford the breadth of staff or do not have the psychological ethos that characterized the enriched home.

With respect to impact, experimental group patients, both newly treated and those who had been receiving antidepressants, improved significantly on 12-week follow-up versus the patients in the comparison group who had been receiving antidepressants. The fact that there were no longitudinal changes in depression among the treated patients in the comparison group suggested that a screening intervention program in these facilities might have led clinicians to adjust the dose of medication for some of those who had been receiving antidepressants. Indeed, based on the recommendations of expert consensus on pharmacotherapy in older depressed patients

(15), 30% of the patients in all the nursing homes who had been receiving antidepressants before the commencement of our study were at “below average” (“starting”) doses, 55% were receiving “average” 6-week target doses, and 11% were receiving antidepressants that experts “would not generally use”; only one subject (4%) was receiving the “usual highest” dose. As Nelson

(16) pointed out, while it is important to “start low and go slow,” it is essential to “keep going,” since older patients often require “usual” final doses. In the experimental homes, one-third of the patients who had been receiving antidepressants had their dose increased after screening. Of note, the modest response (28% improvement on the Cornell scale score) in the experimental group may have reflected the fact that after 12 weeks of treatment, 72% of the patients were still receiving starting doses. A limitation of our study was that we did not examine whether any nonpharmacological strategies were instituted for depressed persons in the experimental homes after their screening that may have contributed to their improvement.

Finally, while mandatory screening complements the Minimum Data Set and serves to facilitate its goal of triggering treatment, it is possible that Medicare may not reimburse psychiatrists if referrals emanate from screening instruments per se. Medicare will reimburse psychiatrists if patients are referred by licensed social workers or primary care physicians. Thus, screening can serve as the impetus for social workers and physicians to refer patients to psychiatrists for further evaluation and treatment.

Although the results of this study must be considered provisional because it was limited to four nursing homes—three of which had a large minority residential population—within one geographical area, our favorable findings with respect to process, outcome, and impact indicate that mandatory depression screening can provide a solution for enhancing the treatment of depression among dementia patients in nursing homes. Moreover, it can ameliorate some of the undertreatment of minorities that has been reported for depression in general

(17). Future research should examine whether the coupling of mandatory depression screening with staff education and nonpharmacological behavioral approaches can further augment treatment recognition and response.