Despite the established link between suicidality and depression, most depressed individuals do not manifest suicidal behavior

(15). Clearly, other factors are important in understanding the link between depression and suicidality in women

(16). To date, most studies of suicidal thoughts and behavior have been restricted to a single domain of potential risk factors (e.g., individual [

17,

18], familial [

19,

20], psychological

[21], or social

[22]). Even within a particular domain, studies have tended to be narrow in their focus. For example, some investigations have compared the relative risk only across specific diagnoses

(23,

24), although more recent research has shown a greater risk of suicidality arising from the presence of comorbid conditions (e.g., anxiety or substance abuse [

6,

25]). Without the comprehensive study of variables from multiple domains, it remains difficult to determine the relative importance and interrelationships among correlates of suicidality.

Given this gap in knowledge, and the higher risk of depression in women, this article examines the relationship between childhood physical abuse and suicidality in a community sample of women with major depressive disorder. The significance of a history of childhood physical abuse is systematically assessed and compared with other important correlates thought to be associated with suicidality. In this study, suicidal ideation and suicide attempt are conceptualized as discrete events and are measured separately.

Results

Approximately 11.3% (N=455) of female respondents under the age of 65 met diagnostic criteria for a lifetime prevalence of major depressive disorder. Of these, 347 respondents had complete information on all variables of interest and were the basis for the following analyses. Most missing data were lost to interview questions regarding recollections/knowledge of parental depression (57 missing cases) and age at onset for own depression (25 missing cases).

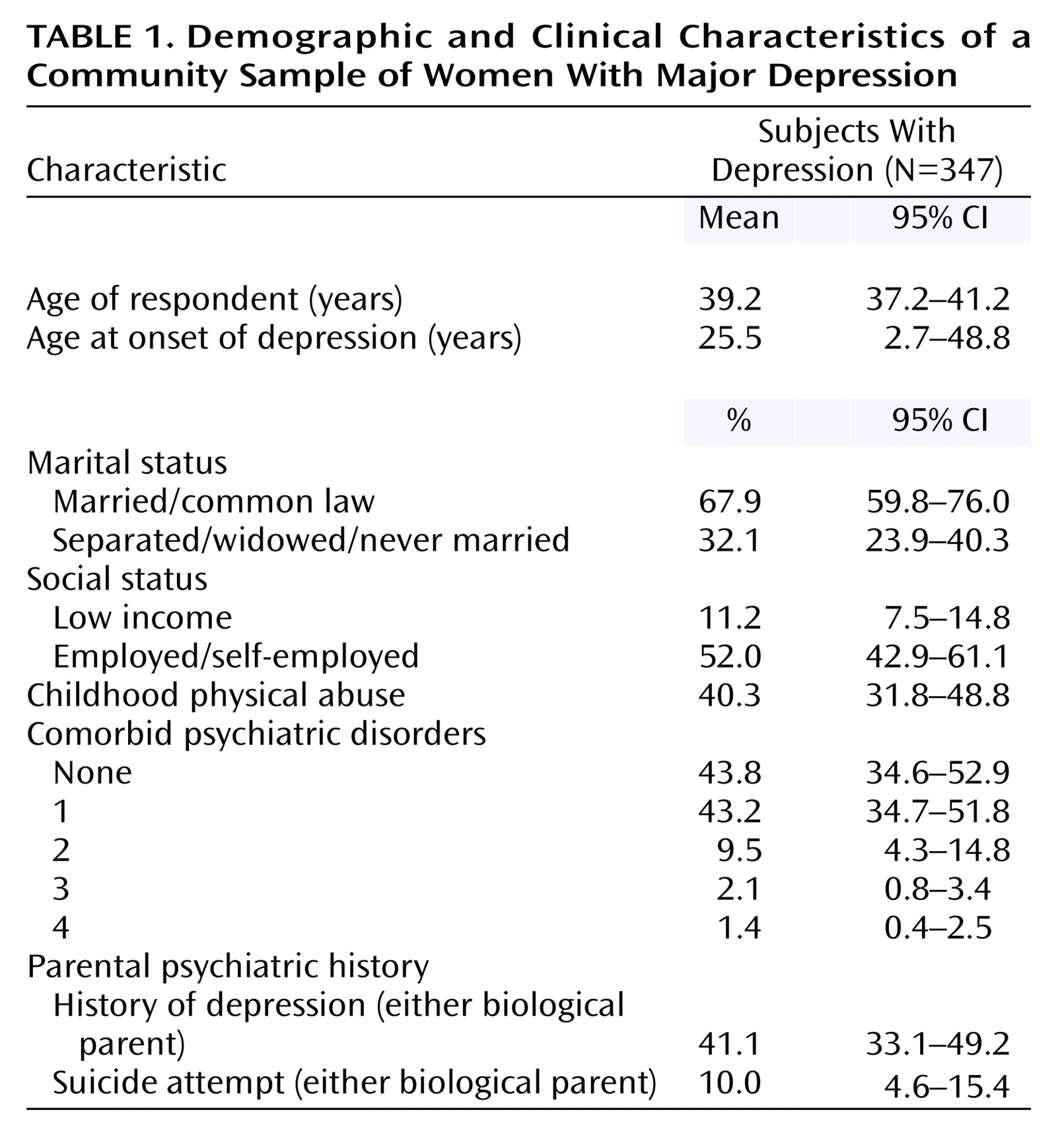

Table 1 outlines the characteristics of the sample. The mean age at onset for depressive symptoms was 25.5 years. More than half the sample (52.7%) met diagnostic criteria for one or two comorbid lifetime psychiatric disorders. Childhood physical abuse was reported by more than 40% of respondents. According to respondent recollections of parental psychiatric history, 41.1% reported that at least one biological parent had exhibited depressive symptoms at some point in time. Of this sample, 10.0% of respondents also reported that at least one biological parent had attempted suicide.

More than half (55.6%, N=193) reported experiencing suicidal ideation at some point in time. Approximately one-quarter (23.9%, N=83) reported making at least one suicide attempt during their lifetime. Significant overlap was noted between the group of respondents who reported suicidal ideation and those who reported a suicide attempt (χ2=47.48, df=1, p<0.001).

Approximately two-fifths (41.5%) of respondents indicated that they both had experienced suicidal thoughts and had made at least one suicide attempt during their lifetime. While more than half (58.5%) of respondents reported suicidal thoughts but no suicide attempts, less than 2% (1.9%) of respondents reported making at least one suicide attempt in the absence of suicidal thoughts.

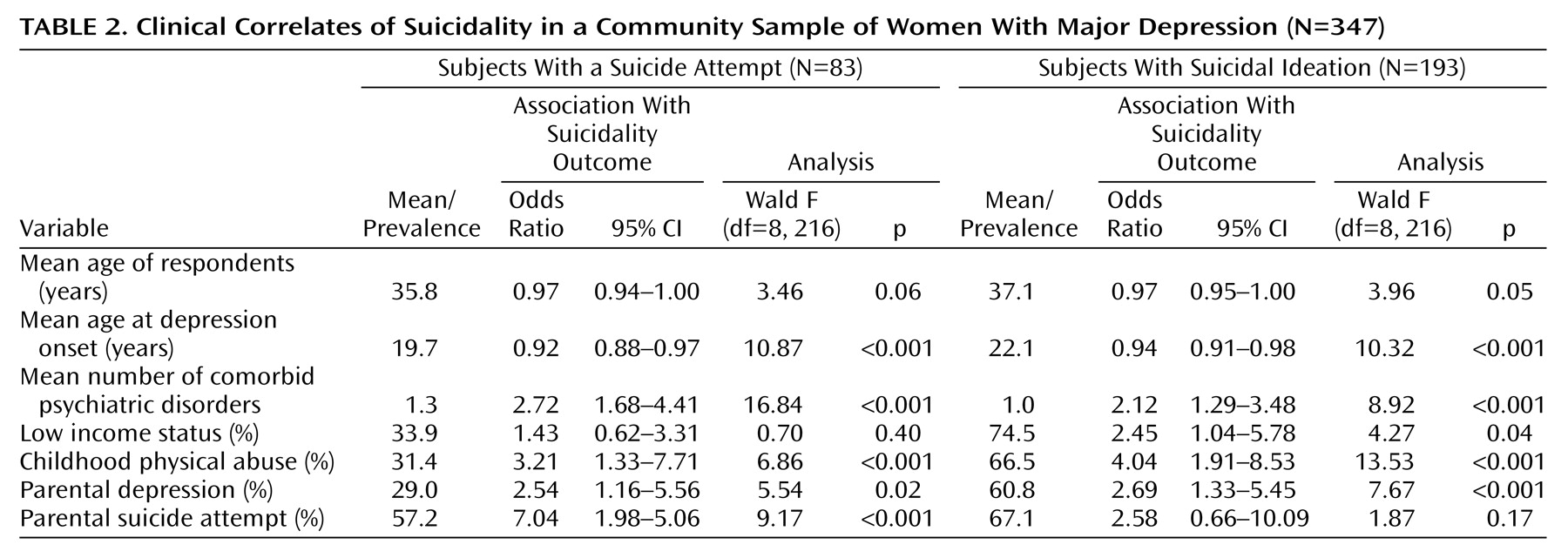

Table 2 presents the bivariate relationships for each suicidality outcome independently. Significant relationships were found between suicide attempt and each correlate, with the exception of respondent’s age and low income status. In comparison, significant bivariate relationships were found between suicidal ideation and each variable, with the exception of parental suicide attempt.

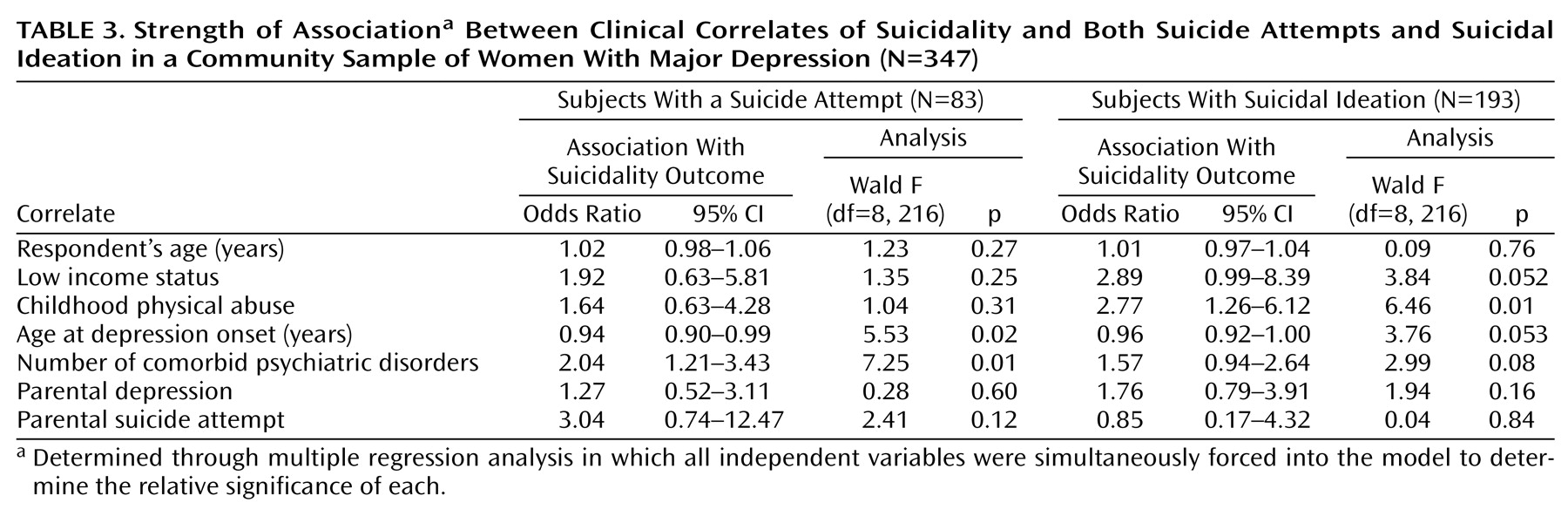

Table 3 presents the strength of association between suicidal ideation, suicide attempt, and selected correlates. For depressed women who reported suicidal ideation, childhood physical abuse was found to be the only significant correlate in the model. A trend toward statistical significance was noted for low income status and age at onset for major depressive disorder.

The number of comorbid psychiatric disorders showed the strongest association with suicide attempt, followed by age at onset. There was a trend toward an increase in the strength of the relationship between the number of comorbid disorders and suicide attempt as the number of comorbid disorders rose. For example, the percentage of respondents who had made a suicide attempt increased from 10.1% among those with one comorbid disorder to 80.3% among respondents with at least four comorbid disorders.

Discussion

Findings from this community sample indicate that women with major depressive disorder are at greater risk for suicidal ideation and attempts. More than half of the sample reported suicidal ideation, and nearly a quarter had made at least one suicide attempt during their lifetime. A significant overlap was found between reports of suicidal thoughts and attempts. Whereas a substantial proportion of women reported ideation but not attempts, women who reported making an attempt rarely did so in the absence of suicidal ideation. As such, suicidal ideation and attempts appear to be correlated, albeit discrete, processes.

One of the most interesting aspects of the current study stems from the opportunity it provides to compare the relative importance of correlates across two components of suicidality. As noted elsewhere

(37), suicide research has been plagued by a lack of consistent definitions and nomenclature for suicidality. Within individual studies, there has been a tendency to target a single aspect of suicidal behavior (e.g., self-harm, suicide attempts, or completed suicide) or to cluster various components under one conceptual umbrella. Within the current study, it was possible to examine suicidal ideation and suicide attempt as two distinct outcomes. From the findings of the present study, it appears that the factors most closely associated with suicidal ideation may vary from those most closely linked to suicide attempts.

Considerable research has focused on the identification of clinical risk factors associated with suicidality. Childhood trauma, in particular maltreatment, has been found to be associated with later adverse mental health outcomes including psychiatric disorder, self-harm, and suicidality. Whereas childhood sexual abuse and “maltreatment” (operationalized as one or more of physical, emotional, and sexual abuse, and/or neglect) have attracted the majority of research attention, to date there have been few studies specific to childhood physical abuse. Findings from the present study are consistent with other work demonstrating a relationship between exposure to one or more types of childhood maltreatment and depression. Among women with major depressive disorder, the prevalence of reported childhood physical abuse (40.3%) was almost double that found within the larger sample of women from which it was drawn (21.1%)

(31).

Furthermore, findings from the present study suggest that a history of childhood physical abuse may be most closely associated with suicidal ideation. For depressed women who reported suicidal ideation, childhood physical abuse was found to be the only significant correlate in the model. Depressed women who had experienced childhood physical abuse were almost three times more likely to experience suicidal ideation in their lifetime. In comparison, a history of physical abuse was not significantly associated with a greater risk for suicide attempts when other correlates were also considered.

Among risk factors for suicidality, psychiatric comorbidity has been identified as an important factor

(4,

25). Findings from the current study confirm the importance of one or more comorbid psychiatric disorders as an important correlate of suicide attempts in this community sample of women with major depressive disorder. Women with major depressive disorder who met diagnostic criteria for at least one other comorbid psychiatric disorder were approximately twice as likely to have also made a suicide attempt relative to those without additional psychiatric conditions.

As a further contribution to our understanding of psychiatric comorbidity as a correlate, the current study allowed us to consider the cumulative impact of comorbidity. Although previous researchers have examined the relative significance of diagnostic categories of comorbidity, it seems plausible that the psychiatric burden of multiple comorbid conditions may itself increase risk. Among depressed women who reported a suicide attempt, a cumulative trend was indeed evident. An increase in the number of comorbid disorders was strongly linked to an increase in the strength of the association between comorbidity and suicide attempts.

In response to the differences in correlates found to be associated with each outcome, these findings may support the development of a pathway model for suicidality. As a nonlinear, multicausal phenomenon, one can speculate that the mechanisms for suicidality are housed in the interaction between an individual’s inherent vulnerabilities (or conversely, resiliencies) (e.g., predisposition to psychiatric disorder, likelihood of developing comorbid conditions, age at onset for psychiatric disorder) and the environmental context while growing up (e.g., exposure to childhood physical abuse, sociodemographic variables). In comparison to suicidal ideation, more lethal components of suicidality (i.e., attempts, completed suicides) may be derived from more severe, chronic, or cumulative exposure to environmental stressors (in the absence of protective factors). As such, whereas early childhood trauma may increase the risk for suicidal ideation, the comorbid nature of an individual’s psychiatric status appears to be the strongest predictor of adult suicidal behavior in women.

Interpretation of this study’s findings requires careful consideration of its methodological limitations. The cross-sectional design of this study precludes measurement of a temporal relationship between suicidal ideation/attempts and the correlates examined. Cause and effect relationships cannot be delineated. Although it is tempting to speculate that the presence of certain correlates such as comorbidity preceded suicide attempts, information regarding the timing of these conditions and events was unavailable. Similarly, although exposure to childhood physical abuse was notably high within this sample, it is not necessarily the case that this adverse childhood experience was directly linked to increased vulnerability to major depressive disorder

(38,

39). Confounding familial and social factors may in fact be associated with both the experience of childhood physical abuse and increased risk for disorder (e.g., dysfunctional and/or impoverished family environments, lack of social support for managing traumatic events). A longitudinal, prospective research design that follows a sample from early childhood and compares those exposed to child maltreatment with their nonmaltreated siblings could address such issues.

Data collection for the current study relied on retrospective reports to assess the prevalence of childhood physical abuse, psychiatric disorder, familial psychiatric history, and aspects of suicidality. As such, it is important to consider potential threats to the accuracy of these reports. For instance, some suggest that the recall of earlier experiences is altered by emotional impairment and psychiatric symptoms. To date, this claim has not been well supported

(40). Nonetheless, this study may have been strengthened if self-report information had been corroborated through multiple informant sources or third-party records. On the other hand, it is possible that externally verified maltreatment may be less critical for psychopathology than the way the event was encoded in the respondent’s mind.

Although different correlates were found to be associated with each of the suicidality outcomes examined, it is also important to note that sample size may have limited the number of factors that emerged across outcomes. Whereas a sufficient sample size was available for suicidal ideation (N=193), the logistic regression analysis for suicide attempt may have been somewhat limited by its smaller sample size (N=83). As a result, the ability to identify further correlates of significance may have been reduced.

Given the established links between depression and suicidality, as well as childhood abuse and adult suicidality, it is important for clinicians to be able to assess for risk of these negative sequelae and to recognize the links with childhood experiences. Clinicians will be best supported in this work through the development and testing of more complex, theoretical models of contributing factors. Further research is required to increase our understanding of the mechanism through which exposure to childhood physical abuse and an individual’s psychiatric history increase risk for suicidality. Without greater insight into the conditions under which such factors contribute to suicidal risk, and the identification of protective factors, clinicians will continue to be restricted in their ability to accurately identify high-risk individuals.