Major depression occurs in 1% to 3% of the general elderly population

(1,

2), and an additional 8% to 16% have clinically significant depressive symptoms

(1,

3). The prognosis of these depressive states is poor. A meta-analysis of outcomes at 24 months estimated that only 33% of subjects were well, 33% were depressed, and 21% had died

(4). Moreover, studies of depressed adults

(5,

6) indicate that those with depressive symptoms, with or without depressive disorder, have poorer functioning, comparable to or worse than that of people with chronic medical conditions such as heart and lung disease, arthritis, hypertension, and diabetes

(7). In addition to poor functioning, depression increases the perception of poor health

(7), the utilization of medical services

(8), and health care costs

(9).

The preceding findings suggest that depression in elderly community subjects is a serious problem. Nonetheless, probably fewer than 20% of cases are detected or treated

(2,

4). Even among those detected and treated, the effectiveness of interventions appears to be modest

(10). Escalating health care costs and shrinking health care resources challenge health care professionals to find more effective and less expensive approaches to depression in the elderly.

The success of a program for preventing delirium among elderly medical inpatients

(11) offers hope that a similar intervention model may be useful in preventing depression among elderly community subjects. This program involved identification of elderly medical inpatients with at least one of six targeted risk factors for delirium and implementation of standardized intervention protocols for each of the risk factors present. The program attenuated the risk factors and reduced the incidence of delirium by 40%. To develop a similar intervention model for preventing depression among elderly community subjects, risk factors for depression in this population must be defined. Thus, the purpose of this investigation was to determine risk factors for depression among elderly community subjects by systematically reviewing original research on this topic. The review process, modified from the one described by Oxman et al.

(12), involved systematic selection of articles, assessment of validity, abstraction of data, and qualitative and quantitative synthesis of results.

Method

Selection of Articles

The selection process involved four steps. First, two computer databases, MEDLINE and PsycINFO, were searched for potentially relevant articles published from January 1966 to June 2001 and from January 1967 to June 2001, respectively. For MEDLINE, the key words “depression,” “risk factor,” and “aged” and the text word “community” were used; for PsychINFO, the same words were used as text words. Second, relevant articles (judged on the basis of the title and abstract) were retrieved for more detailed evaluation. Third, the bibliographies of relevant articles were searched for additional references. Finally, all retrieved articles were screened to determine which met the following six inclusion criteria: 1) original research published in English or French, 2) study group of community residents, 3) subjects age 50 years or older, 4) prospective design that excluded subjects who were depressed at baseline (or controlled for baseline depression in the analysis), 5) study of at least one risk factor for depression, and 6) acceptable definition of depression (either recognized diagnostic criteria or cutoff on a depression rating scale).

Assessment of Validity

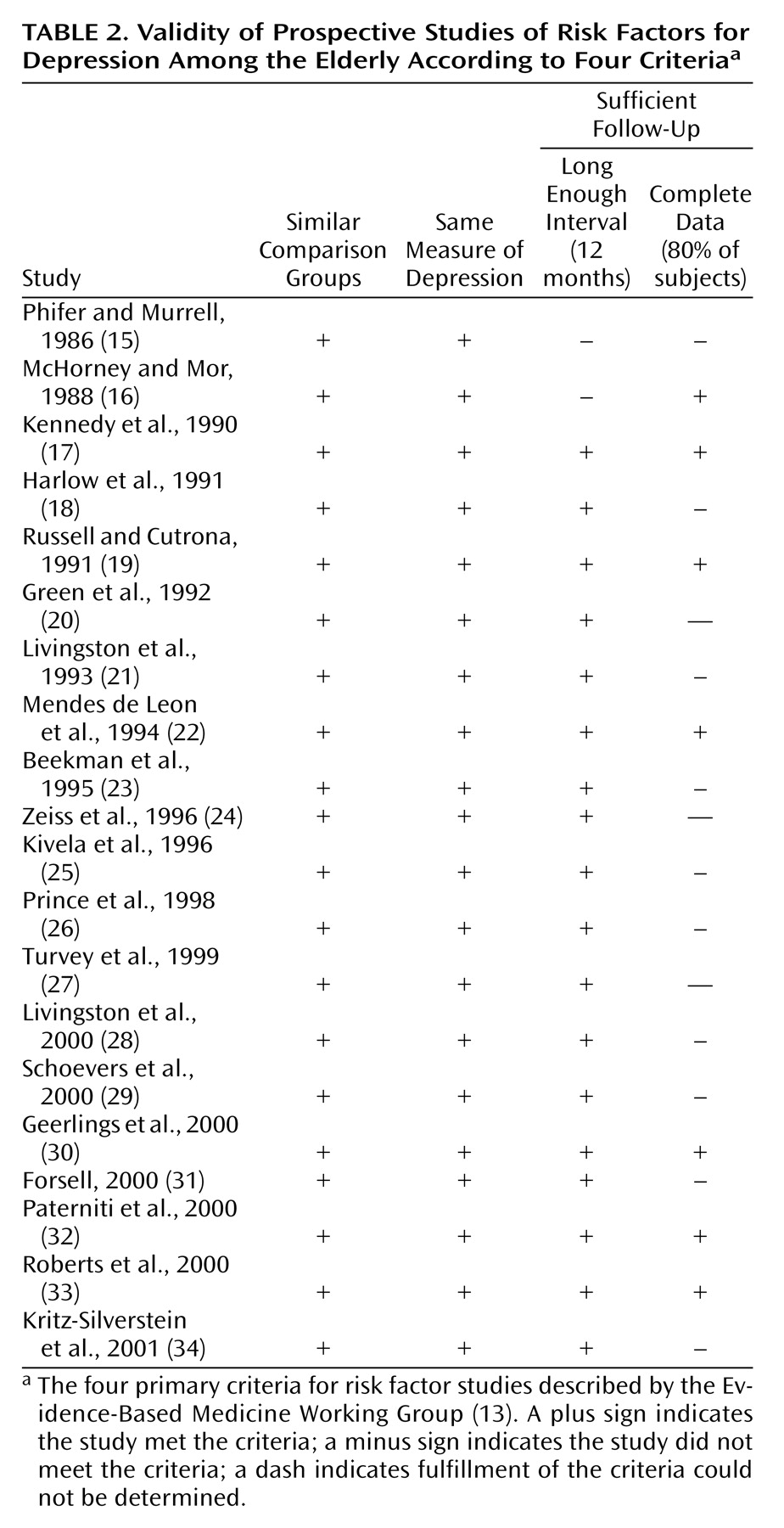

To determine validity, the methods of each study were assessed according to the four primary criteria for risk factor studies described by the Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group

(13): 1) clearly identified comparison groups that were similar with respect to important determinants of outcome, other than the one of interest (or analysis that controlled for differences in important determinants), 2) measurement of exposures and outcomes in the same way, 3) a sufficiently long follow-up (i.e., 1 year), and 4) a sufficiently complete follow-up (i.e., including 80% of inception cohort). Each study was scored with respect to meeting (+) or not meeting (–) each of the these criteria.

Abstraction of Data

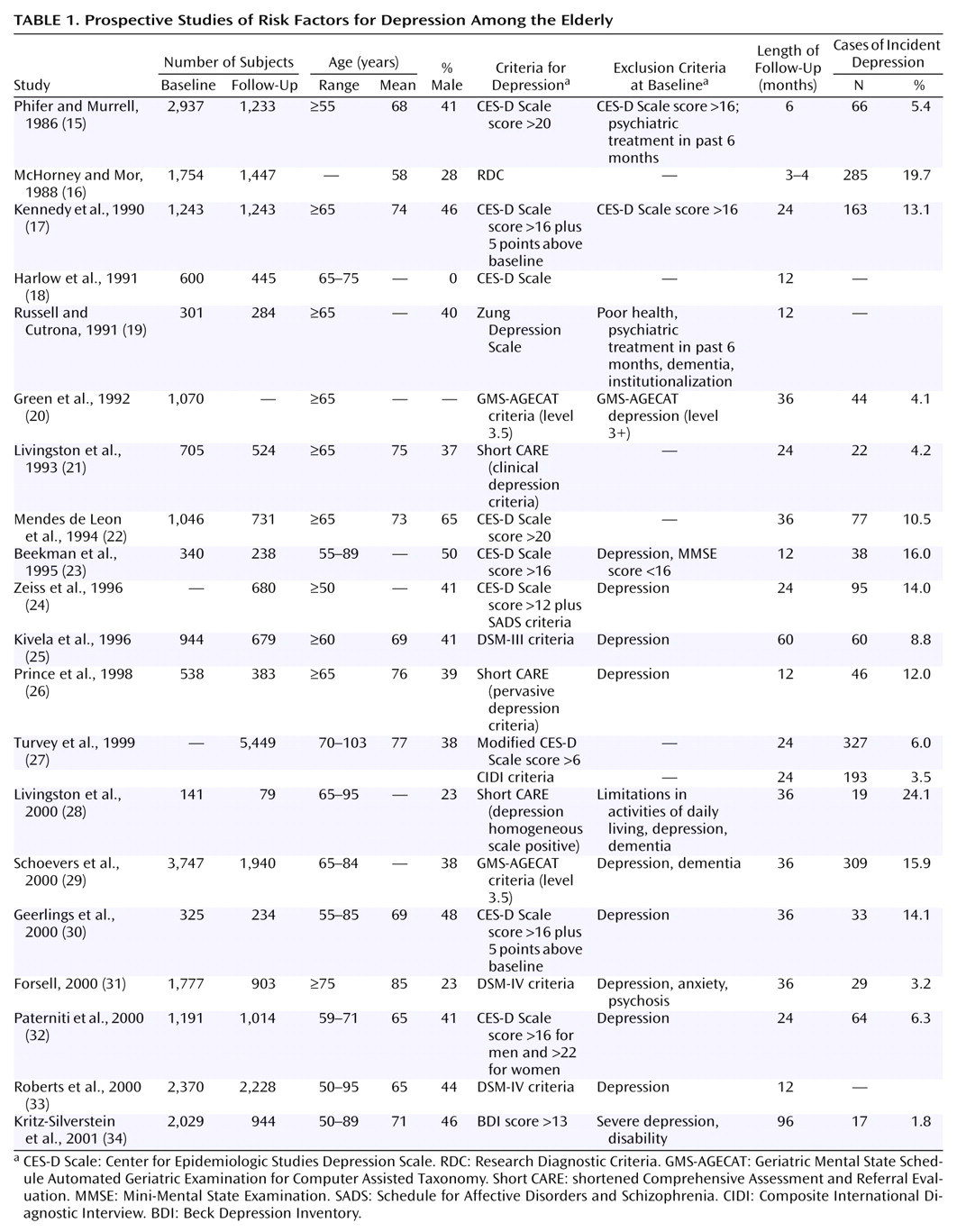

Information about the size of the study group at baseline and follow-up, subjects’ age, proportion of men, criteria for depression, exclusion criteria at baseline, length of follow-up, number of incident cases of depression, and risk factors was abstracted from each report.

Data Synthesis

Qualitative

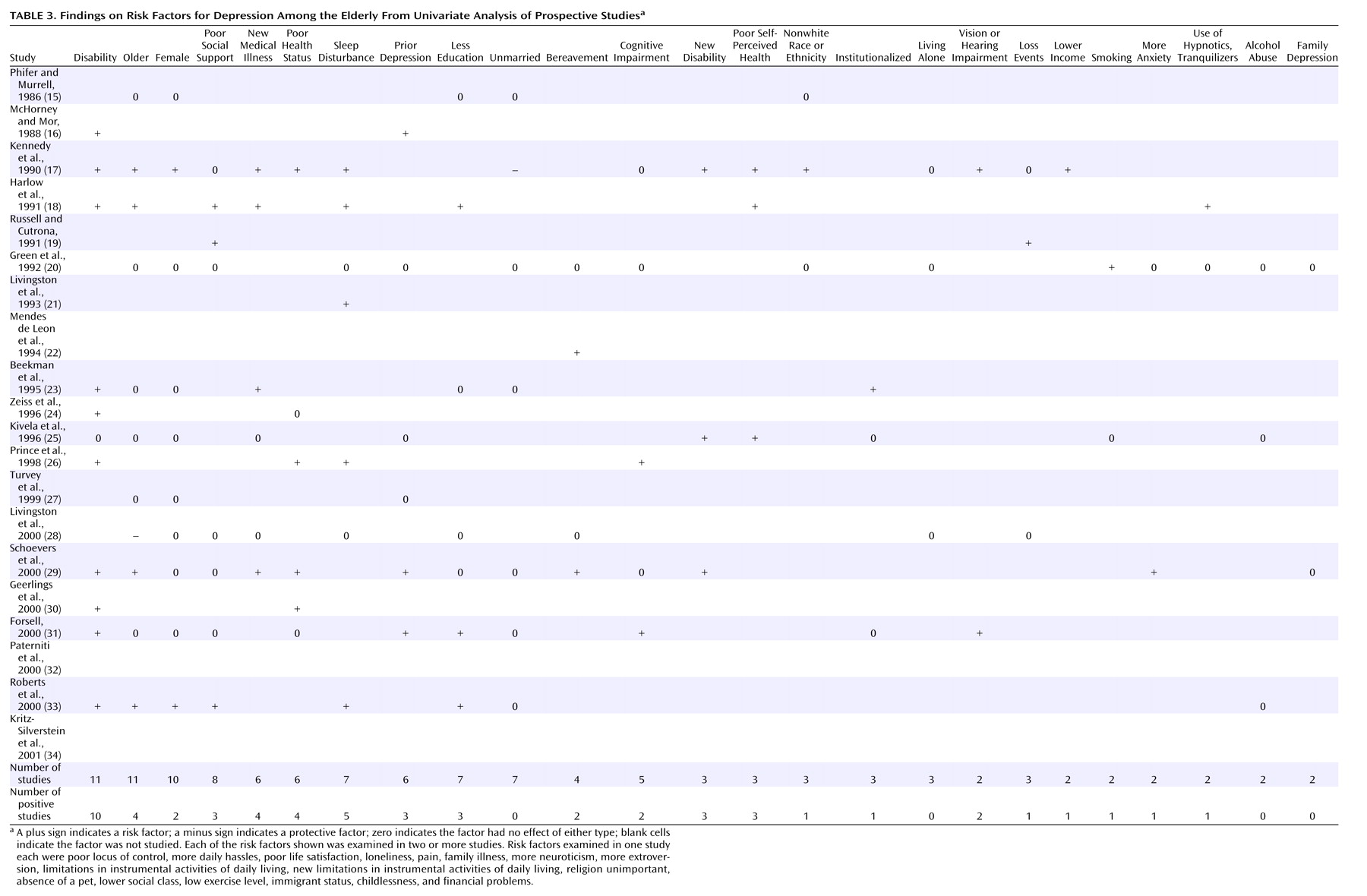

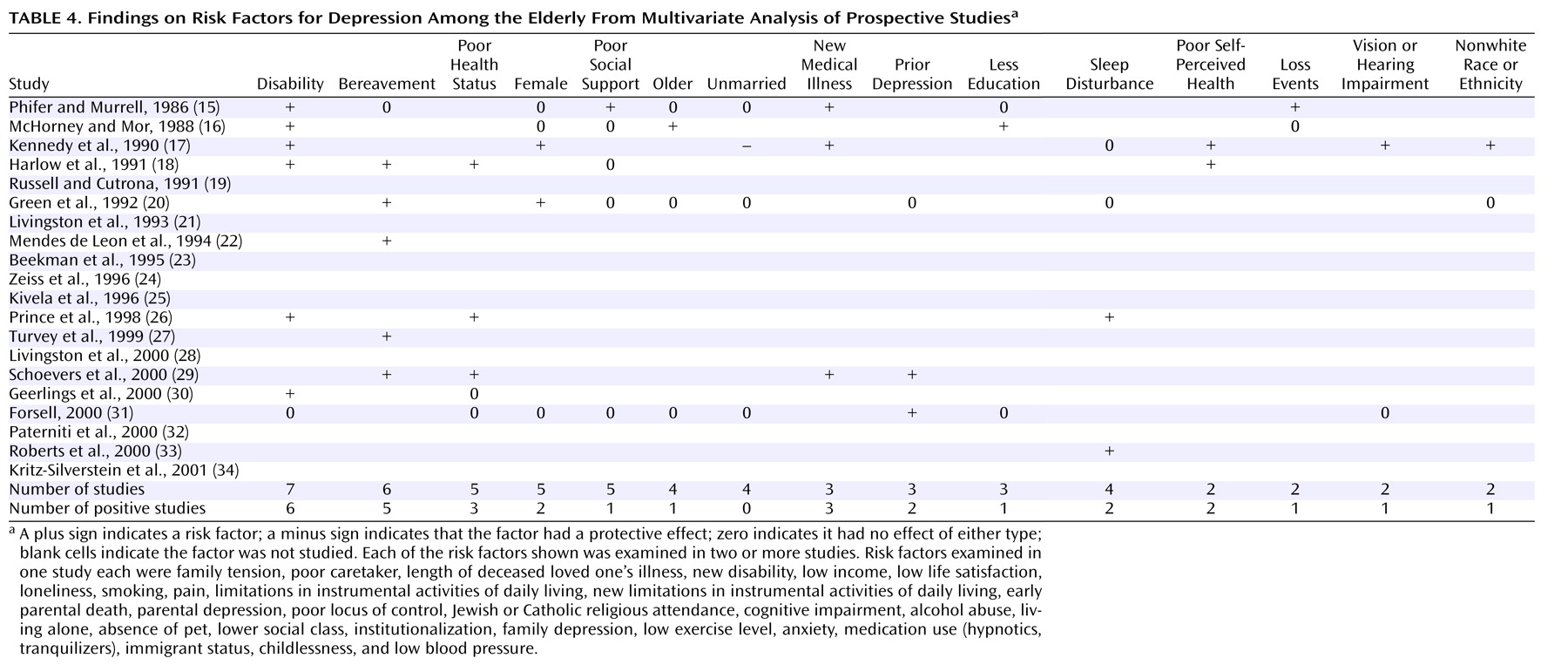

All abstracted information was tabulated. A qualitative meta-analysis was conducted by summarizing, comparing, and contrasting the abstracted data.

Quantitative

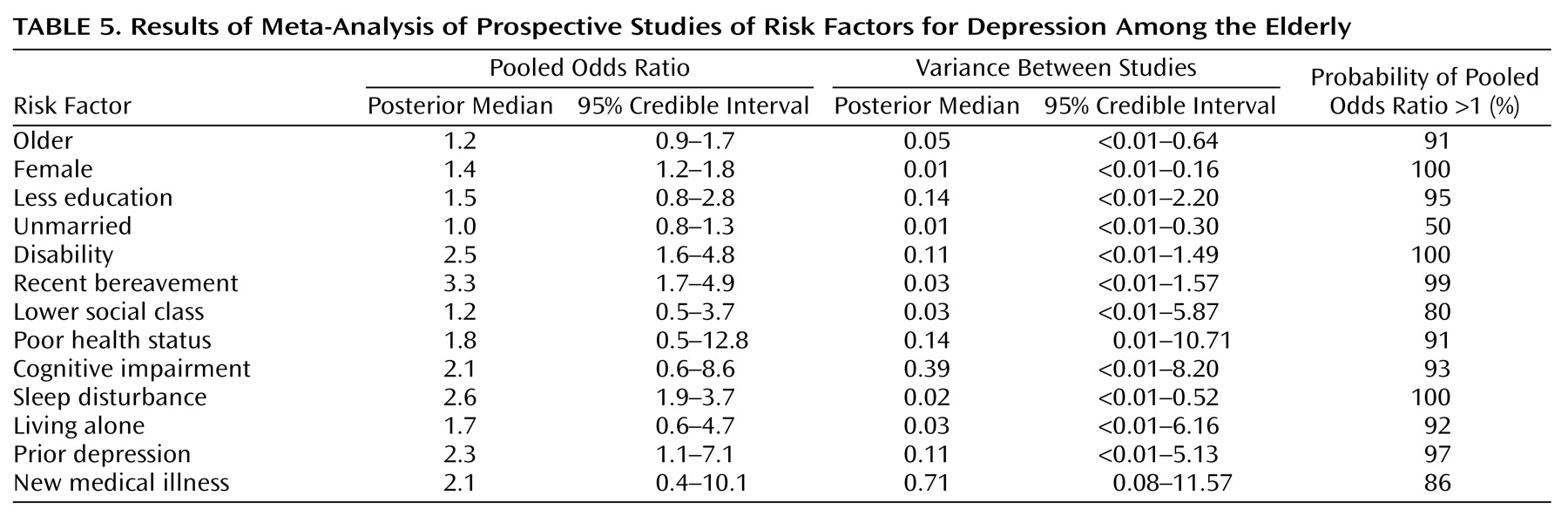

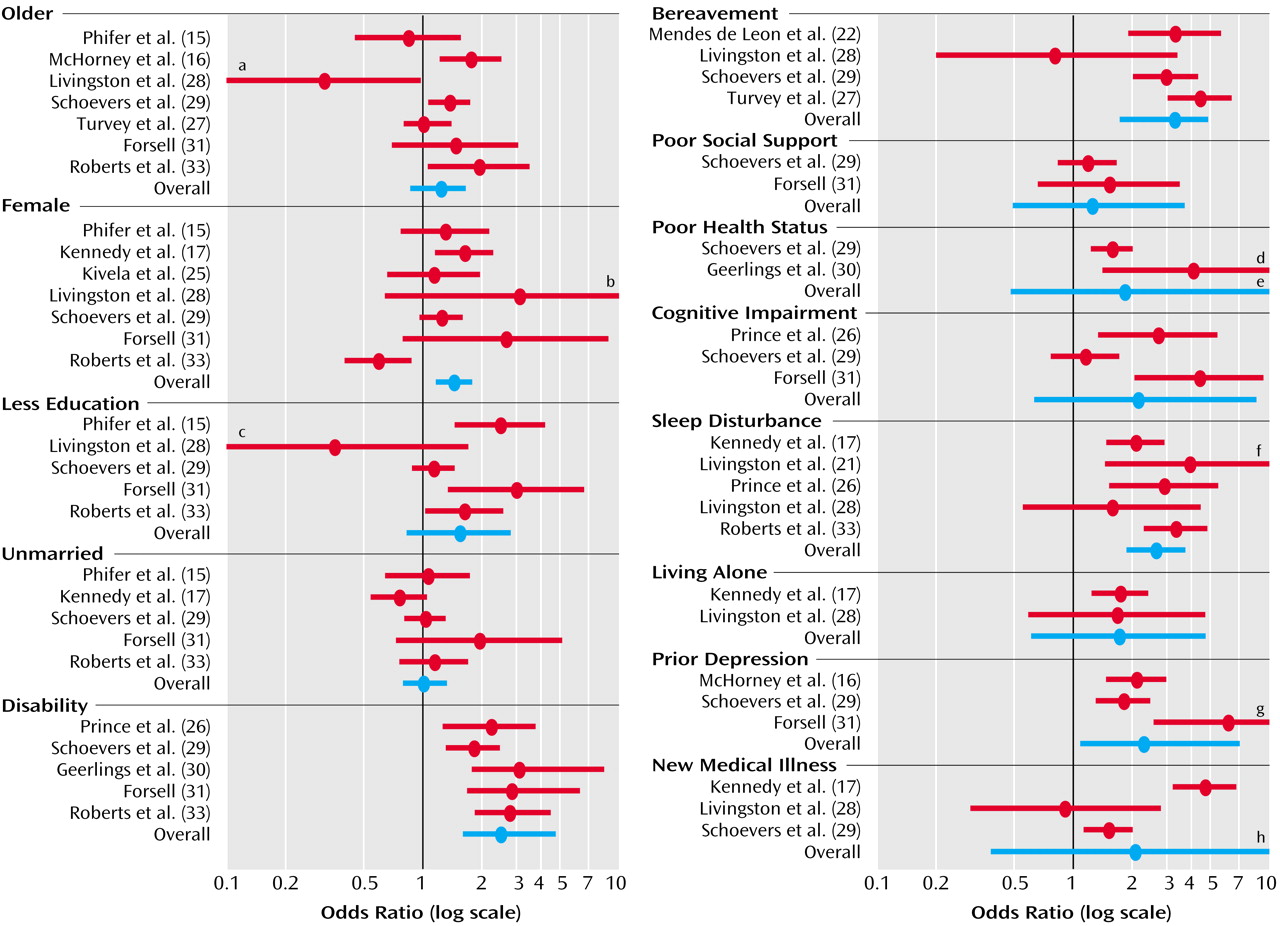

A quantitative meta-analysis was conducted for risk factors with usable data from two or more studies. To obtain a pooled estimate of the odds of depression associated with each risk factor, we conducted a meta-analysis using a Bayesian hierarchical (random effects) model

(14). In the Bayesian framework, information available before the analysis is combined with the observed data to obtain a posterior distribution for the parameters of interest

(14). We assumed no prior information was available. The variance between odds ratios from different studies is a measure of the heterogeneity of the studies. A Bayesian 95% posterior credible interval may be interpreted in a straightforward manner as an interval that contains the parameter of interest with 95% probability given the observed data. We also estimated the probability that the pooled odds ratio was greater than 1.

Discussion

The combined results of 20 prospective studies of risk factors for depression among elderly community subjects indicate that five factors (bereavement, sleep disturbance, disability, prior depression, and female gender) are significant risk factors for depression. The median interval between the determinations of risk factor status and depression status was 24 months.

Notably, three of these risk factors are potentially modifiable, namely, bereavement, sleep disturbance, and disability. Based on the pooled odds ratios data in this meta-analysis, the attributable risks for these three risk factors were 69.4% (95% credible interval=42.2–79.5), 57.0% (95% credible interval=35.7–73.3), and 56.5% (95% credible interval=20.4–83.5), respectively. Thus, a large proportion of depression among elderly people in the community may be attributed to one of these risk factors. Because these risk factors are frequent in elderly community subjects, their modification could be expected to have an important public health impact.

Elderly populations could be screened to identify individuals at high risk of depression (e.g., bereaved women with prior depression, disability, and sleep disturbance). Subsequently, these individuals could be targeted for interventions to abate the three potentially modifiable risk factors and reduce the risk of depression. Such interventions might include education about the significance of the risk factors, bereavement counseling and support

(35), new skills training, “maintenance of routines” protocols

(36), enhancement of social supports

(37), individual or group therapy to facilitate adjustment to loss of function

(38), and sleep enhancement protocols

(39).

These five risk factors may serve two other purposes

(40). First, they could identify whole populations at high risk of depression and aid the development of population-based interventions to reduce the frequency of depression. Second, they could focus treatment on the most important putative contributing factors (e.g., bereavement, loss of function, sleep disturbance).

The finding that bereavement is an important risk factor for depression contradicts the results of the Epidemiologic Catchment Area (ECA) study

(41), which indicated low rates of bereavement-related depression in the elderly. However, it has been argued that the ECA study probably failed to diagnose the low-level symptomatic forms of depression experienced by many elderly

(42).

This review has 10 potential limitations. First, the search of the literature was conducted by one author only. Second, the search was limited to articles published in English or French. Third, we did not assess publication bias, although it is unlikely that this bias influences publication of risk factor studies. Fourth, the data were abstracted by one author only. Fifth, follow-up of the enrolled cohort was incomplete in most studies; however, the results of studies with and without complete follow-up were similar. Sixth, examination of depression status was complicated by differences in the length of follow-up; nonetheless, there were no consistent differences in reported risk factors by length of follow-up. Seventh, the examination of the results of the univariate and multivariate analyses was complicated by differences in the definitions of some risk factors from one study to the next, and the examination of the results of the multivariate analyses was complicated by adjustments for different variables in different studies. Eighth, we have identified with some confidence five factors that increase the risk of depression and four factors (higher age, lower education level, being unmarried, poor social support) that do not appear to increase the risk of depression; however, many potential risk factors have not been studied adequately. Ninth, in this meta-analysis, we could not determine whether the simultaneous presence of multiple risk factors results in a cumulative increase in the risk of depression; however, the results of four studies included in this meta-analysis

(15,

18,

19,

29) suggest that different risk factors play both additive and interactive roles. Finally, there was heterogeneity in the results for some risk factors (i.e., lower education level, disability, poor health status, cognitive impairment, prior depression, new medical illness), perhaps related to different definitions of these variables in different studies and small study groups in some studies; consequently, the results of the meta-analysis for these risk factors must be interpreted cautiously.

To conclude, five risk factors for depression among elderly community subjects include bereavement, sleep disturbance, disability, prior depression, and female gender. Despite the methodologic limitations of the studies and this meta-analysis, these findings may guide efforts to develop programs to prevent depression in this population.