Personality disorders are characterized by long-standing and pervasive dysfunctional patterns of cognition, affectivity, interpersonal relations, and impulse control that cause considerable personal distress (DSM-IV)

(1,

2). In subjects with personality disorders, psychosocial impairment and the use of mental health resources are high

(3–

5). The prevalence of patients with personality disorders in inpatient and outpatient psychiatric populations is high (e.g., the prevalence of borderline personality disorder is estimated to be between 15% and 25%

[6]). However, there is a considerable lack of empirical research on treatment of personality disorders with psychotherapy, with only a few randomized controlled studies

(7). To address concerns about costs of mental health services, empirical data about the efficacy of psychotherapy in the treatment of personality disorders are needed. There is evidence that psychotherapy in general is an effective treatment for personality disorders

(7,

8), but existing studies indicate that outcome may differ for different forms of psychotherapy

(9,

10) and different personality disorders

(11,

12).

For this reason, this review examined the effects of the two most frequently applied forms of psychotherapy in the treatment of personality disorders, psychodynamic therapy and cognitive behavior therapy. Our review addressed the following questions:

Since only a few randomized controlled treatment studies exist, we included both controlled and naturalistic treatment studies.

Method

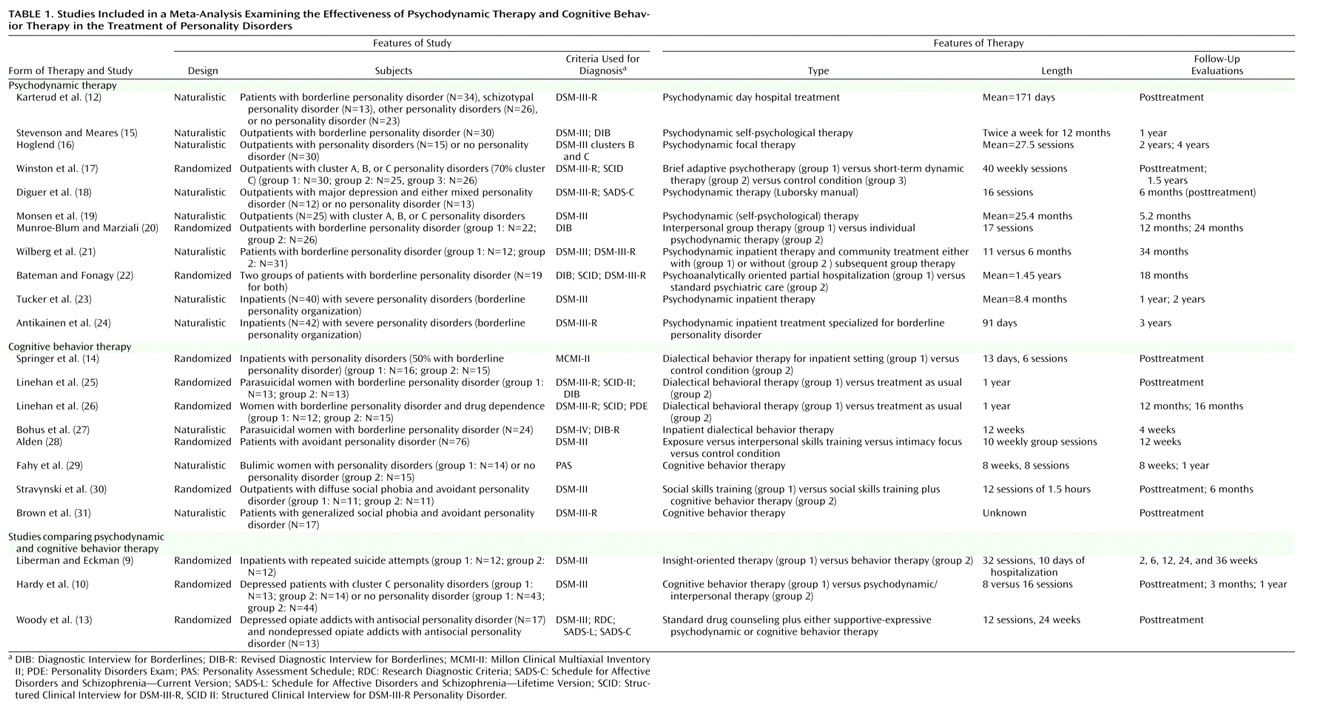

We collected studies of psychodynamic therapy and cognitive behavior therapy that were published between 1974 and 2001 by carrying out a computerized search using MEDLINE, PsycINFO, and Current Contents. We included studies that 1) examined specific and explicitly described forms of psychodynamic therapy or cognitive behavior therapy, 2) used standardized methods for diagnosing personality disorders, 3) used reliable and valid instruments for the assessment of outcome, and 4) reported data that allowed calculation of within-group effect sizes or assessment of personality disorder recovery rates.

In order to assess long-term change after psychotherapy, we selected the longest posttreatment follow-up for evaluation.

Twenty-two studies met these inclusion criteria

(9,

10,

12–31). Three of these studies examined the effects of both psychodynamic therapy and cognitive behavior therapy

(9,

10,

13). Since there were only three randomized controlled studies for psychodynamic therapy and five for cognitive behavior therapy, we calculated within-group effect sizes for all studies by using Cohen’s d

(32). For each measure, we subtracted the posttreatment mean from the pretreatment mean and divided the difference by the pretreatment standard deviation of the measure. If there was more than one patient group, we calculated a pooled baseline standard deviation, as suggested by Rosenthal

(33). If necessary, signs were reversed so that a positive effect size always indicated improvement. Whenever multiple measures were applied in a study, we assessed the effect size for each measure separately and calculated the mean effect size in order to assess the overall outcome of the study. We computed both unweighted effect sizes and effect sizes weighted by the sample size in order to yield unbiased estimators of effect sizes

(34). Since Cohen’s d gives the amount of change in units of the standard deviation, a standardization of different scalar values of outcome measures is achieved. However, different outcome measures may be more sensitive to change than others (e.g., measures of depression versus measures of personality traits). Thus, the effect sizes of different outcome measures may not be comparable. For this reason, it may be useful to assess effect sizes for certain (classes of) outcome measures separately

(33). Therefore, we not only computed an overall effect size but also assessed effect sizes separately for measures that were more specific to the core pathology of personality disorders. Furthermore, we assessed effect sizes for self- and observer-rated measures separately, thus taking different observer perspectives into account. If necessary, we used other statistics reported than means and standard deviations (e.g., t or chi-square statistics) to calculate effect sizes

(32). If studies included patients with and without personality disorders, effect sizes were calculated separately for both groups. There was a problem with the study of Woody et al.

(13), which pooled the results of the two forms of therapy that were applied. Since the authors found no significant differences between the two forms of therapy applied, we decided to include this study and used the resulting pooled effect sizes as estimates for both forms of therapy. Since the differences between treatments were not significant, no systematic error is implied by this procedure. There was a similar problem with the study of Springer et al.

(14), which did not report pre- and posttreatment means and standard deviations for the outcome measures. They reported t values of outcome data for the total sample of patients in the therapy and the control condition. Since they did not find significant differences between the therapy and the control condition in outcome measures, we decided to use these data to estimate the effect sizes of the inpatient cognitive behavior therapy condition. We included these studies so as not to reduce the already small number of studies. However, were these studies not included, the results would not change substantially.

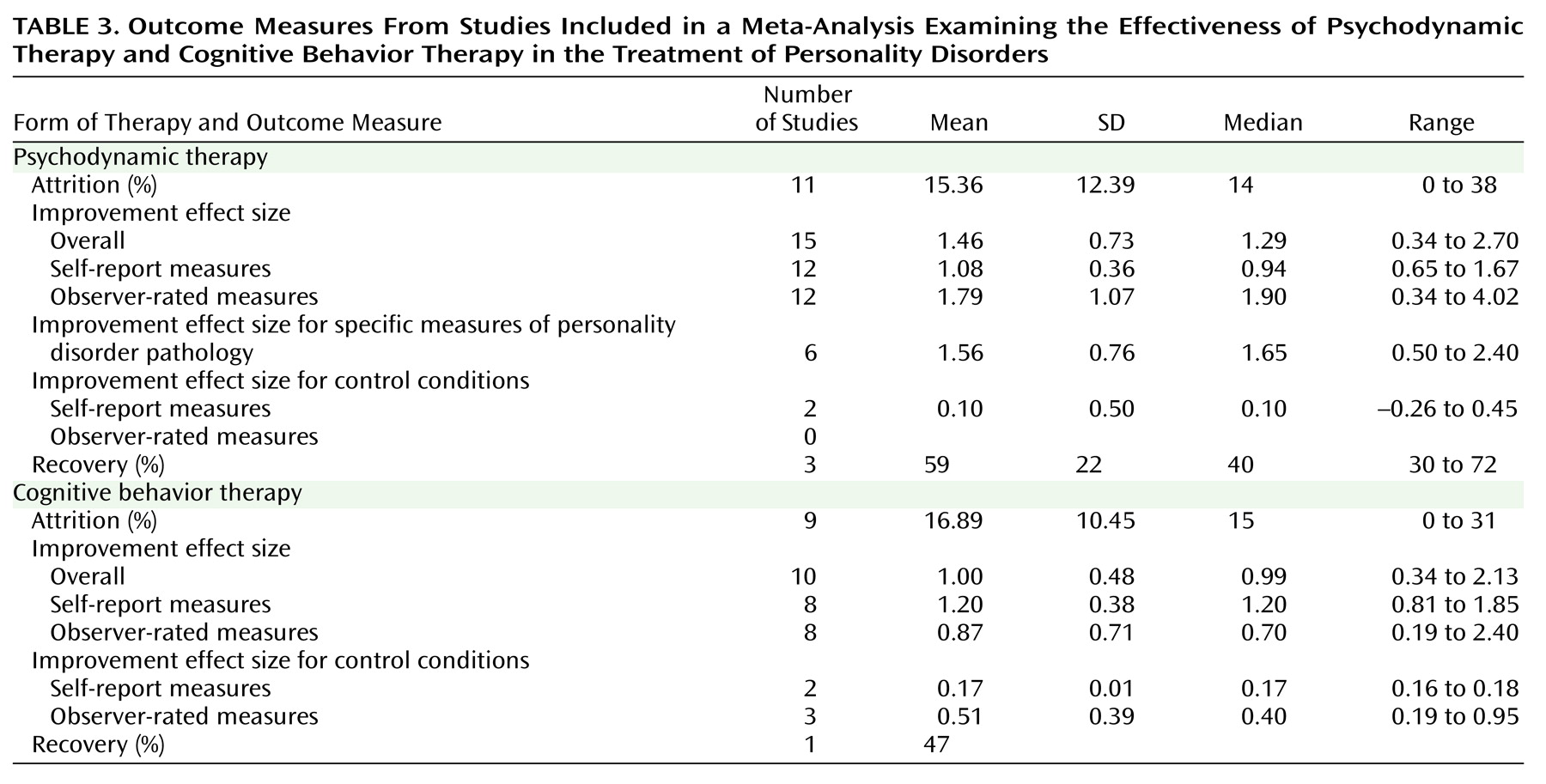

Effect sizes are only one measure of effectiveness. The percentage of patients who recovered or in whom was seen a reliable or clinically significant change in the target measures is even more important. For this reason, we assessed rates of improvement whenever possible.

We calculated correlations between outcome and the following factors: length of therapy, patient gender, inpatient versus outpatient status, use of therapy manuals, clinical experience of therapists as reported in the studies, and study design (randomized versus naturalistic).

Discussion

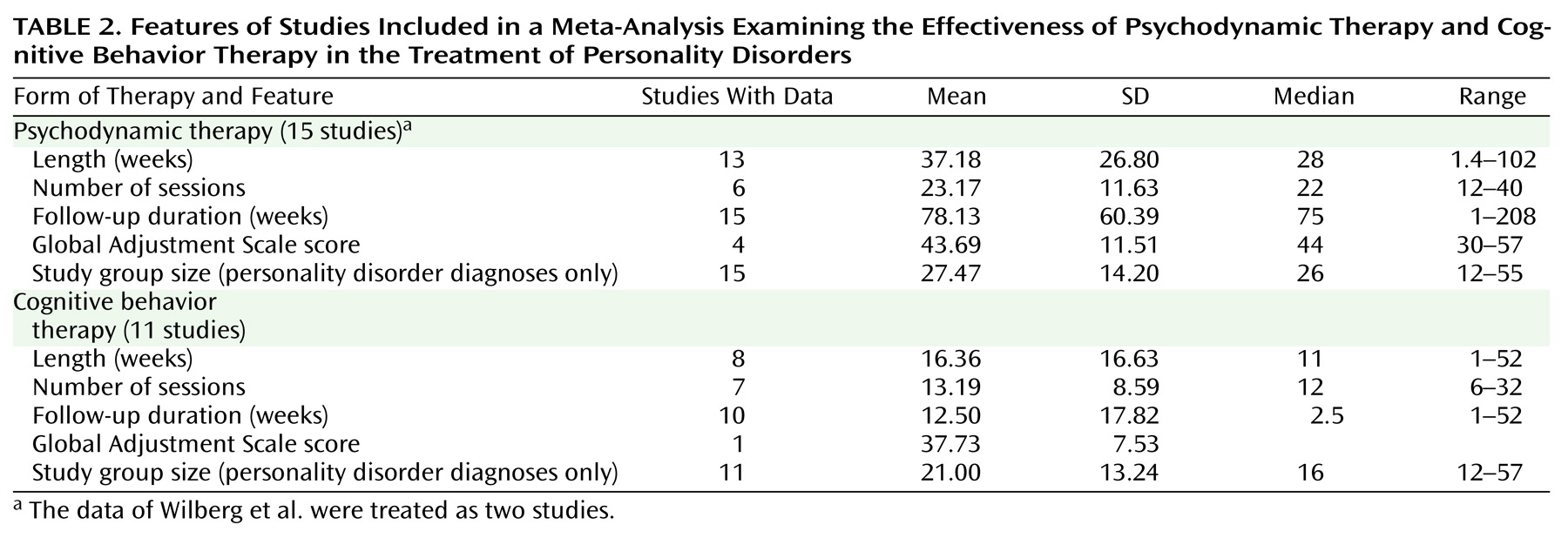

This review addressed the effectiveness of psychodynamic therapy and cognitive behavior therapy in the treatment of personality disorders. One major limitation of this meta-analysis is the small number of studies that could be included: 14 studies of psychodynamic therapy and 11 studies of cognitive behavior therapy. The small number of studies reduces both the results’ potential generalization and the statistical power

(32). Thus, the conclusions that can be drawn are only preliminary.

With regard to the potential generalization to community populations, the dropout rates are relevant. The mean dropout rates for psychodynamic therapy and cognitive behavior therapy were 15% and 17%, respectively. These rates are below the dropout rate reported by the NIMH study of depression for patients with a personality disorder, which was 31%. The total number of subjects treated for personality disorders in the studies of psychodynamic therapy was N=417; for cognitive behavior therapy, the corresponding study group size was 231.

Since the data of the longest follow-up period were used for this review, the effect sizes indicate long-term rather than short-term change in personality disorders. This is particularly true of the psychodynamic therapy studies, which had a mean follow-up period of 1.5 years (78 weeks), whereas the mean follow-up period for the cognitive behavior therapy studies was considerably shorter (13 weeks).

The effect sizes cannot be compared directly between cognitive behavior therapy and psychodynamic therapy because the data do not come from the same experimental comparisons. The studies differed with respect to various aspects of therapy, patient samples, outcome assessment, and other variables.

Within-group effect sizes may be an overestimate of the true change because of unspecific therapeutic factors, spontaneous remission, or regression to the mean. However, in the two randomized controlled studies of psychodynamic therapy

(17,

22), the mean effect sizes for psychodynamic therapy exceeded that of the control condition. This was also true for the patients of the Bateman and Fonagy study in an 18-month follow-up

(37). For cognitive behavior therapy, three randomized controlled studies

(25,

26,

28) reported that cognitive behavior therapy was superior to a control condition.

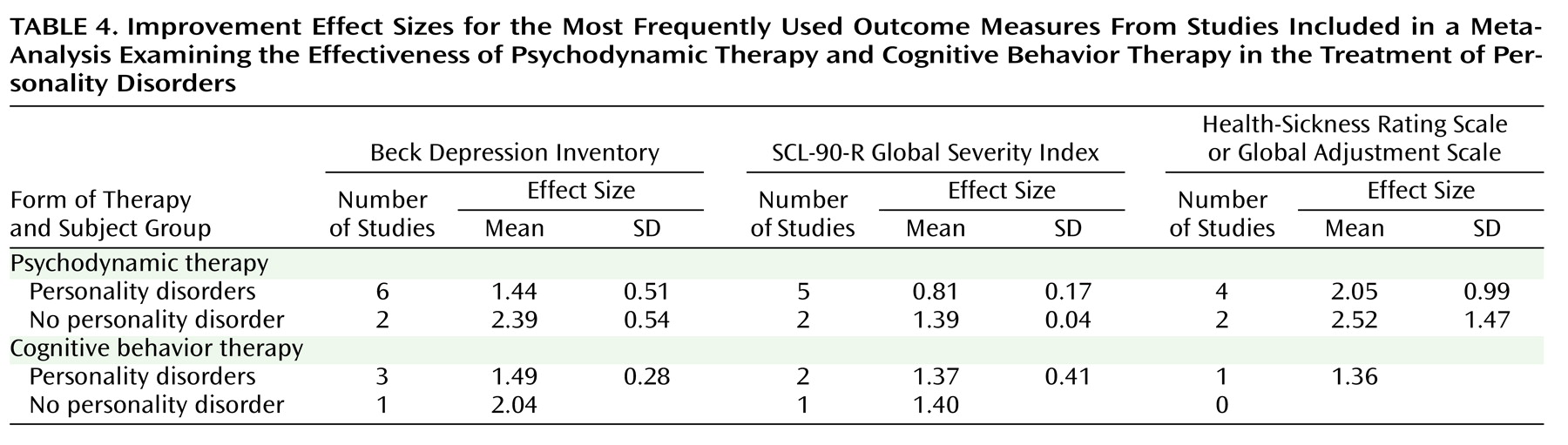

The most frequently used outcome measures were the Beck Depression Inventory, SCL-90-R, and Global Adjustment Scale/Health-Sickness Rating Scale, which are broad measures of symptom severity and level of functioning and are nonspecific in nature. Thus, it is not clear from the data of these instruments if the corresponding effect sizes refer to changes in the personality disorders themselves or to improvements in axis I psychopathology. According to the results of this meta-analysis, both psychodynamic therapy and cognitive behavior therapy yielded significant improvements in more specific measures of personality disorder pathology.

Most of the patients studied who had personality disorders had comorbid axis I pathology. This is especially true of severe personality disorders such as borderline personality disorder. Studies that included patients with both axis I and axis II pathology

(10,

12,

18) reported more pathological pretreatment scores (SCL-90-R global severity index, Health-Sickness Rating Scale, Beck Depression Inventory, Present State Examination) for patients with personality disorders than for patients who had axis I pathology only.

Three studies of psychodynamic therapy reported rates of recovery from personality disorders. The mean recovery rate was 59%. However, defining remission as no longer meeting the criteria of the disorder at a single point in time is debatable. Significant fluctuations over time may occur that may be state dependent rather than showing lasting remission of the personality disorder in question

(40–

42). Long-term follow-up evaluations are necessary to study recovery from personality disorders.

Several studies reported more improvement in personality disorder patients after longer treatment durations

(12,

16,

43). These results are consistent with the findings reported by Shea et al.

(44) and Diguer et al.

(18) for depressive patients with and without personality disorders and with the results of Kopta et al.

(45), who found that improvements in character problems take longer than symptom changes. For patients with avoidant personality disorder, Alden

(28) noted that changes patients made during a 10-week treatment were insufficient to consider them healthy. Perry et al.

(8) estimated the length of treatment necessary for patients to no longer meet the full criteria for a personality disorder (recovery). According to these estimates, 50% of patients with a personality disorder would recover by 1.3 years or 92 sessions and 75% by 2.2 years or about 216 sessions. Certainly, these estimates can only be preliminary, and more studies are necessary to test if these estimates can be generalized.

There is evidence that treatment with psychotherapy in personality disorder patients is relevant to the cost of health care utilization. In a randomized controlled study of high utilizers of psychiatric services, Guthrie et al.

(46) showed that short-term psychodynamic-interpersonal therapy was significantly superior to treatment as usual with regard to the reduction of distress and the cost of health care utilization. Since certain subgroups of patients with personality disorders are high utilizers of psychiatric services (e.g., patients with borderline personality disorder), these results are relevant for the treatment of personality disorders with psychotherapy.

In a recent meta-analysis, psychodynamic therapy and cognitive behavior therapy proved to be equally effective treatments for depression

(47). According to the results presented in this review, there is evidence that psychodynamic therapy and cognitive behavior therapy are effective treatments of personality disorders. Further research should examine specific forms of psychotherapy for specific types of personality disorder. In order to ensure both internal and external validity, both naturalistic and randomized controlled studies are necessary. Outcome measures should focus not only on axis I pathology but also on core psychopathology. Data on health economics should be included.