Step 2: Conceptualization of Context and Perspective

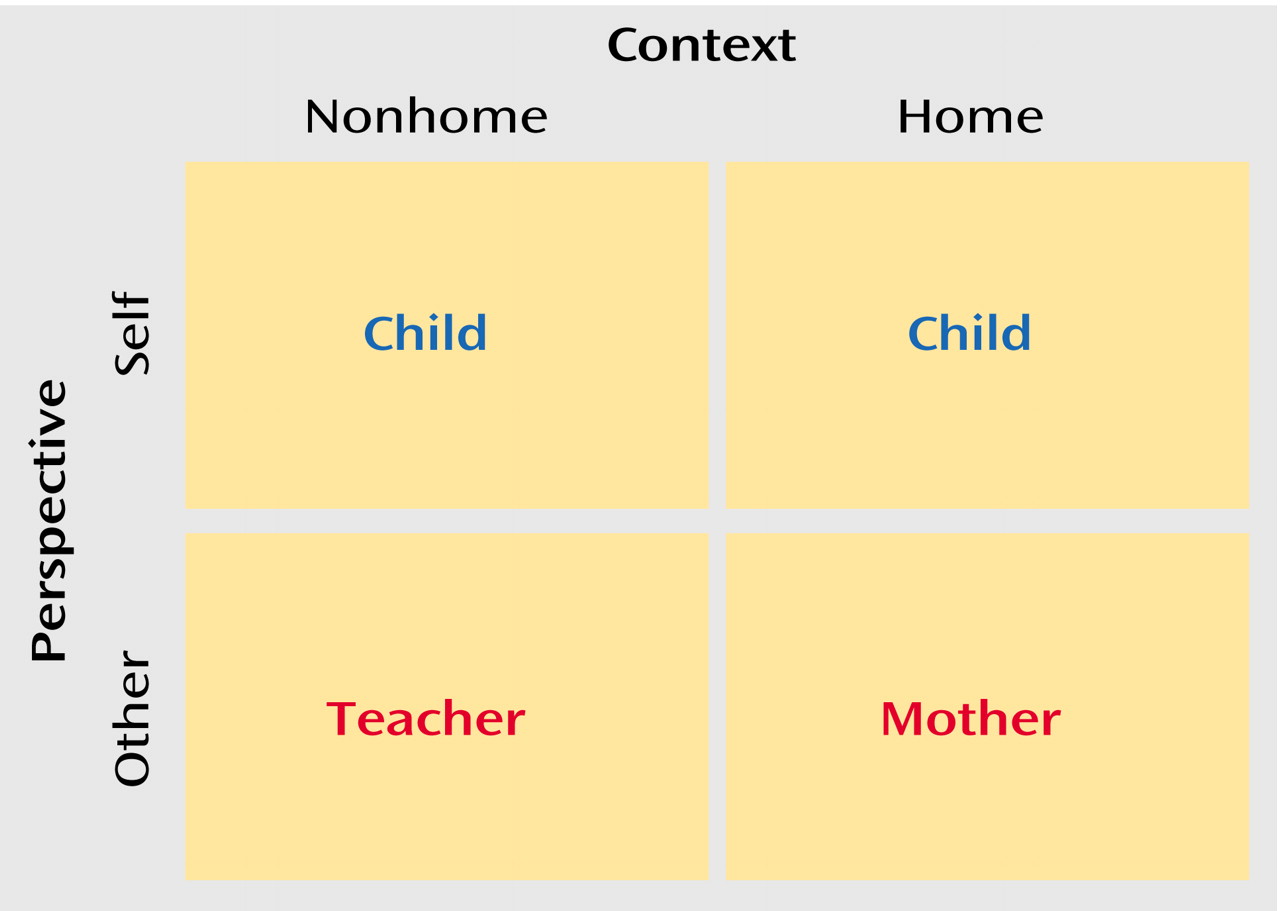

Next, the investigators would consider the totality of contexts and perspectives for which there are informants who are likely to provide reliable and to some degree valid data for the target characteristic. Then the challenge is to divide the totality of contexts envisioned into two or more broad categories that are 1) mutually exclusive, 2) broad enough to span contexts, and 3) likely to influence the expression of T as differently as possible, on the basis of one’s knowledge of the field. For a young child, these categories might be home versus nonhome. For a teenager, it might be more appropriate to contrast home versus school versus other setting, in the expectation that the expression of the characteristic in settings away from both home and school may be informative. In the same manner, the investigator would divide the totality of perspectives into two or more broad perspectives that are likely to influence informants’ reports as distinctively as possible. For a young child, such perspectives might include self, parent, and nonparent; for an older child, they may include self, parent, adult nonparent, and peer. Then the mix-and-match criteria would require contrasting informants with the same perspectives in different contexts and those in the same context with different perspectives.

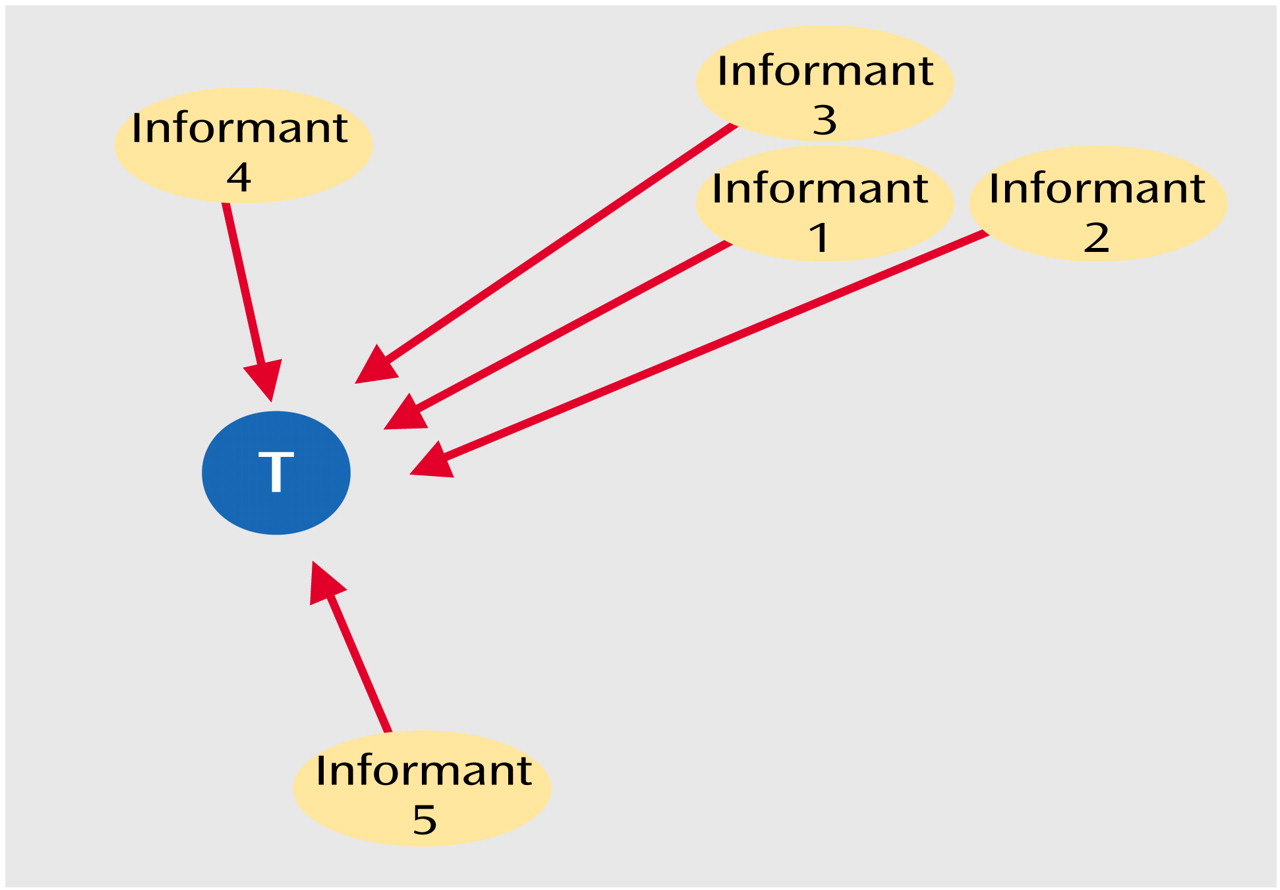

In general, it can be shown that if there are c contexts and p perspectives (hence cp cells), the minimal number of informants to fill the cells is cp, but the minimal number of informants to satisfy the mix-and-match criterion is c+p–1. Thus, with two contexts and two perspectives (hence four cells), the minimal number of informants is three. With three contexts and two perspectives (hence six cells), the minimal number of informants is four. With three contexts and three perspectives (hence nine cells), the minimal number of informants is five. The difficulties of finding many reliable and valid informants militate against too complex a conceptualization of context and perspective.

This process creates a context-by-perspective grid, within which each possible, reliable, and at least minimally valid informant fits in one or more cells. Informants should be selected to fill at least three cells of the grid in such a way that each pair of contexts is seen in some one perspective, and each pair of perspectives is seen in some one context. By using this mix-and-match strategy, each of the informants is asked for an evaluation of the target characteristic for each child in the sample.

For example, suppose two contexts (home and nonhome) and two perspectives (self and other) were selected for a given research question as shown in the grid in

Figure 2.

There are three possible informants in this example: child, teacher, and mother. Note that, by virtue of all cells being filled, the self perspective and other perspective are covered in the nonhome context as well as the home context, and the contrast of nonhome versus home is seen both from the self perspective and from the other perspective. Thus, this choice of informants (even when the two child reports were combined to avoid correlated errors) satisfies the mix-and-match requirement.

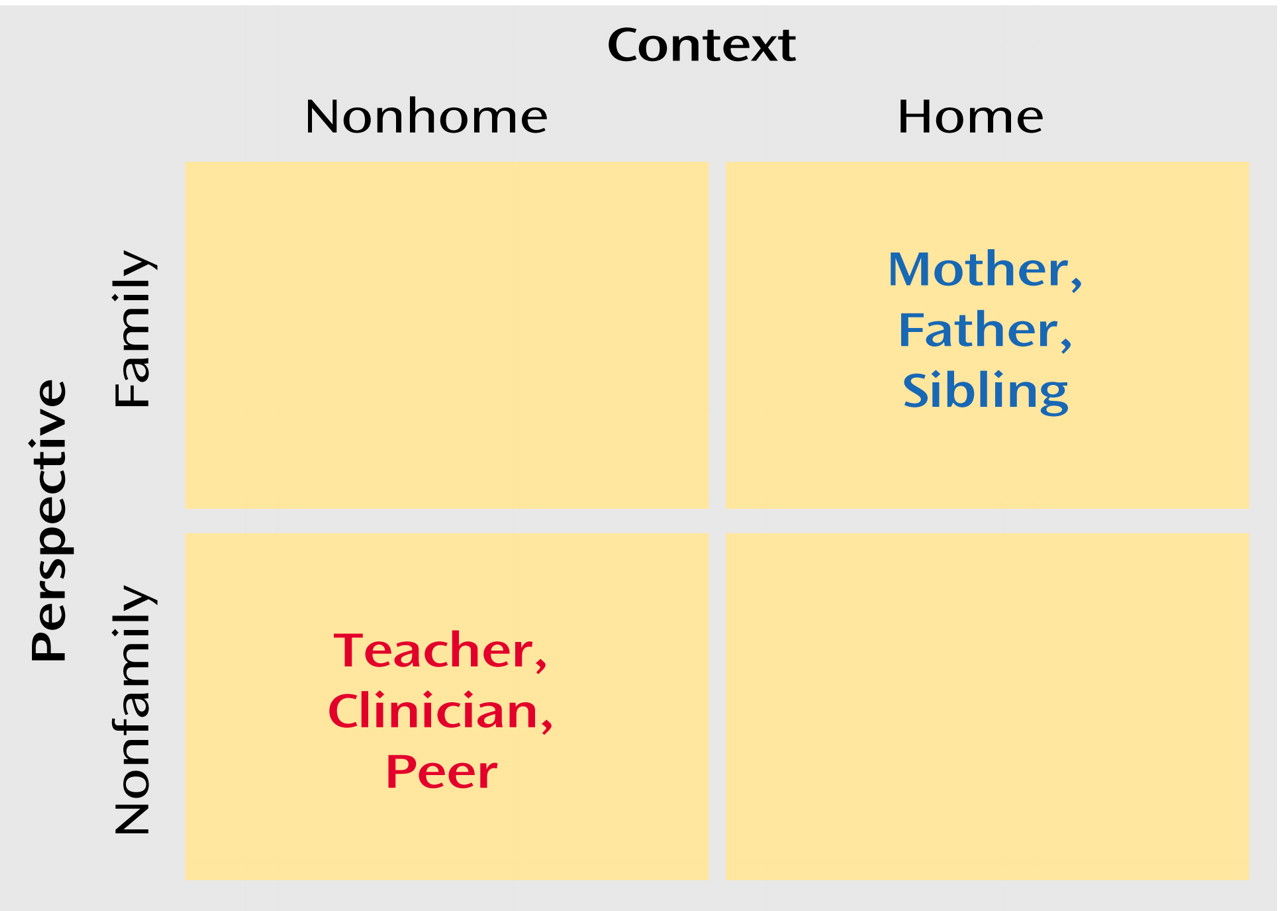

Sometimes self versus other, important as that conceptualization of perspective might be, is simply not possible (e.g., with infant subjects). Then we would have to limit perspective to the subspace of other. We might reconceptualize perspective as family versus nonfamily, with “family” including mother, father, siblings, and other relatives, and “nonfamily” including teachers, clinicians, peers, etc. The minimal number of informants necessary would still be three. However, no combination of mother, father, teacher, and clinician would now satisfy the mix-and-match criterion. Yet the most common combinations of informants in child assessments include these perspectives, as seen in the grid shown in

Figure 3.

Could we, having mother, father, and teacher readily available, somehow reason backwards and find some conceptualization for which these informants would satisfy the mix-and-match criterion? For example, if the teachers are predominantly women, perhaps we could conceptualize perspective as male versus female. Then mother and father would match on context and contrast on perspective. Mother and teacher would match on perspective and contrast on context. If the conceptualization ill suits the situation (such as the conceptualization of male versus female, which ill suits the current example), the approach will not work (as we will show), but of course serendipity might favor such an attempt.

Clearly there are many possible ways to conceptualize context and perspective, some of which will, and some of which will not, satisfy the mix-and-match criterion. Some conceptualizations will succeed better than others because they reflect a better understanding or knowledge of the field. For example, as shown in

Figure 1, one could choose any pair of noncollinear informants to implement triangulation. However, the accuracy of that determination reflects the precision of each informant and the degree of orthogonality between the informants. Thus, a poor choice of informants will result in failed triangulation.

Step 3: Implementation

Once the multiple informants have been selected, subjects are selected from the population of interest, and each informant is asked to report independently on the characteristic of interest for each selected subject. This set of observations is then subjected to principal-component analysis. Principal-component analysis is a mathematical model based on the assumption that the multiple informants’ reports are each linear combinations of orthogonal latent variables, as many such latent variables as there are informants per subject. These combinations of variables are labeled in descending order of the percentage of variance explained as the first, second, etc., principal components. Since every informant is selected to provide reliable and at least minimally valid data for T, and since this criterion is the only construct putatively common to all the informants, if the selection of multiple informants is well done, the first principal component should weight each informant’s data in the same direction, although not necessarily equally. The factor score on this first factor is a multi-informant estimate of T (which we denote as T*), which is largely free of the effects of C and P and is less affected by E than is any single informant’s measure. The second and third factors should correspond to contrasts in context (C*) and perspective (P*) that were built into the choice of informants. Since T*, C*, and P* are linear combinations of data from reliable informants, they should each be reliable. However, T* should be valid for T. Since C* and P* are designed to measure the influence of context and perspective on the expression or reporting of the trait that is independent of the trait itself, C* and P* are constructed to be invalid for T.

It should be emphasized that C* and P* may be interesting variables in their own right. For example, if perspective is structured as self versus other, P* would indicate how discrepant the child’s view of him/herself is from the view of others observing the child (e.g., mother and teacher). Such a measure itself may be an indication of a lack of self-awareness in the child or a lack of sensitivity in the adults. That we are here trying to remove the influence of C and P in order to focus on T reflects the goal of this effort to obtain a gold standard measurement of T and does not gainsay the importance of C and P. In fact, an understanding of how both context and perspective influence informants’ responses is necessary for successful application of these principles.