The pathogenesis of schizophrenia is hypothesized to involve abnormal neurodevelopment

(1,

2). A subtype of schizophrenia has been identified that has a relatively homogeneous genetic etiology associated with a microdeletion on chromosome 22q11.2

(3). The genetic syndrome associated with this deletion, 22q11 deletion syndrome (22qDS), has a variable physical and neurobehavioral phenotype that includes schizophrenia

(3,

4). High rates of congenital dysmorphic features

(5,

6), developmental structural brain abnormalities

(7), and cognitive dysfunction

(8) in 22qDS are consistent with this subtype of schizophrenia, representing an especially neurodevelopmental form of the illness

(2,

3). The genetic risk for schizophrenia is related to the deletion, which usually occurs as a spontaneous (de novo) mutation and in the absence of a family history of psychotic illness

(9,

10). Individuals with 22qDS represent a particularly high-risk group

(9): 25% or more are estimated to develop schizophrenia

(4). The only groups at higher risk are individuals with two parents with schizophrenia or monozygotic co-twins of individuals with schizophrenia. A 22qDS subtype of schizophrenia may be present in up to one in 50 patients with schizophrenia

(11). Higher rates of 22qDS may be present in subsets of schizophrenia with childhood onset or dual diagnosis schizophrenia and mental retardation

(9). Individuals with 22qDS would therefore represent a relatively prevalent (≥1/4000 of the general population

[12]) and identifiable

(3) high-risk group for schizophrenia, well suited for studies of predictive features.

For a 22qDS subtype of schizophrenia to be accepted as a useful model for schizophrenia in general, researchers must be assured that the schizophrenia phenotype is similar to that in other forms of schizophrenia. Clinicians may also wonder if there are specific features of the schizophrenia phenotype that could be used to help identify patients with a 22qDS subtype of the illness (22qDS-schizophrenia). For example, there is some evidence that impulsivity may be a component of the adult neurobehavioral phenotype of 22qDS

(5), but it is unclear if there are differences in core schizophrenic symptoms in 22qDS-schizophrenia. There are few studies detailing the clinical phenotype in adults with 22qDS-schizophrenia, however. Sample sizes have been small, particularly if one considers individuals without mental retardation (six or fewer subjects)

(4,

5,

13). Differences in ascertainment between these small samples and inclusion of subjects with mental retardation may explain why different studies have proposed age at onset to be younger

(5,

13) and older

(4) in 22qDS-schizophrenia than in schizophrenia without 22qDS.

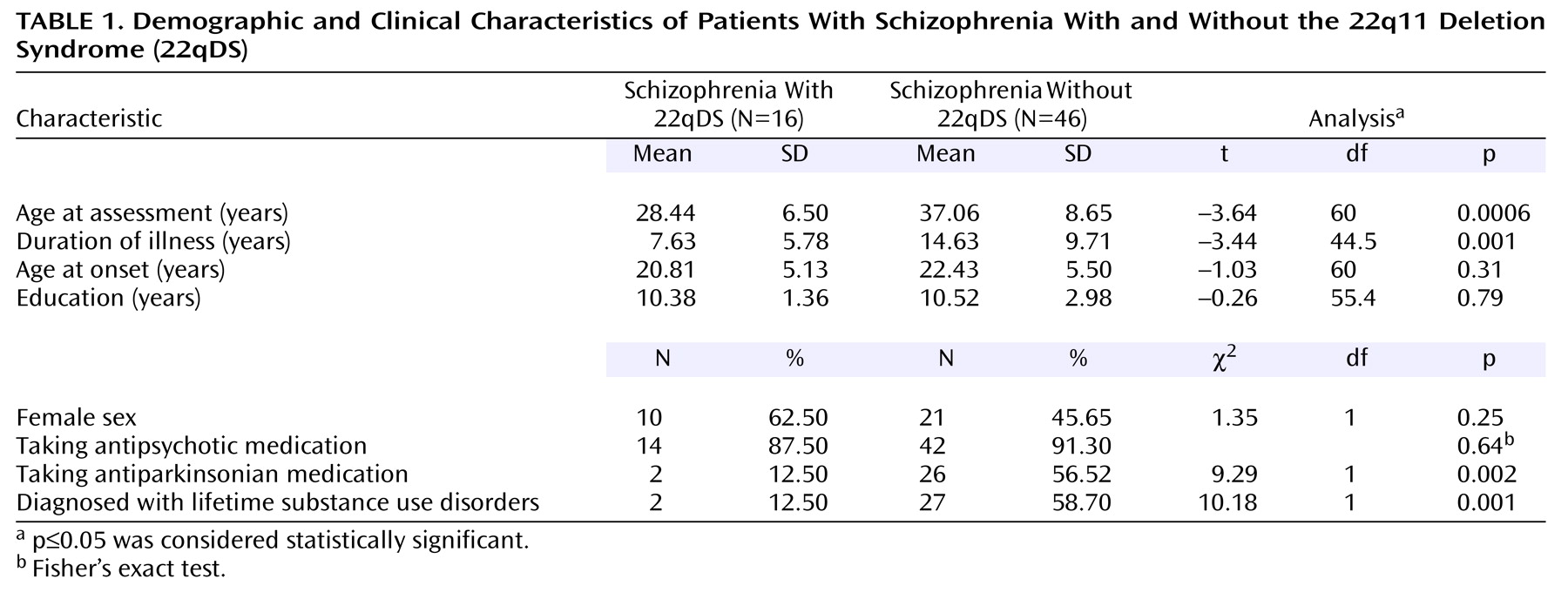

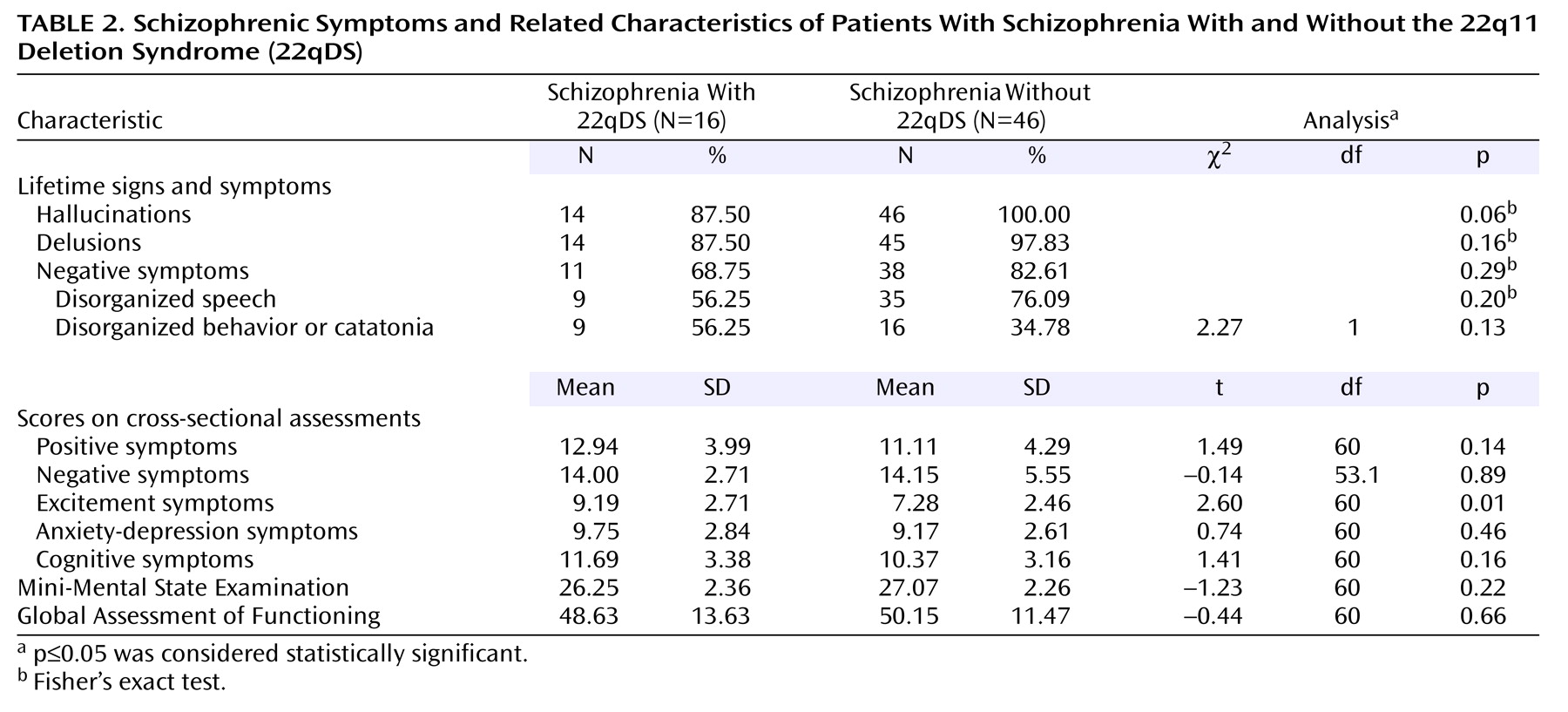

We investigated the largest group of subjects with 22qDS-schizophrenia yet reported to our knowledge (N=24). Our goal was to determine the similarities and differences of the schizophrenia phenotype from other, more typical groups of patients with schizophrenia. We studied a subgroup of individuals with 22qDS-schizophrenia who did not have mental retardation to eliminate potential confounders due to mental retardation and make our study group more comparable to subjects with schizophrenia usually studied. We hypothesized that age at onset and core signs and symptoms of 22qDS-schizophrenia would be similar to those of patients with schizophrenia without 22qDS. We further hypothesized that the 22qDS-schizophrenia group would have greater severity of the excitement symptom grouping, which includes an item on impulse control.

Discussion

The results of this study indicate that the schizophrenia phenotype of a 22qDS etiologic subtype of the illness is largely indistinguishable from other forms of schizophrenia. The longitudinal and cross-sectional features of schizophrenia in patients with 22qDS-schizophrenia are similar to those reported for other groups of patients with schizophrenia (DSM-IV)

(23,

24). Any differences appear to be in auxiliary features of the illness rather than in the major phenotypic features of schizophrenia, such as onset, course, and core symptoms. These results concur with previous reports indicating that the schizophrenia in 22qDS appears relatively typical in terms of symptoms and age at onset

(5,

13,

31). They differ from one study’s conclusions that there is a clinical subtype of schizophrenia associated with 22qDS, including later age at onset and fewer negative symptoms

(4).

Ascertainment of subjects has undoubtedly played a role in differences between studies. When patients with 22qDS-schizophrenia are recruited from groups of patients with schizophrenia, as in the current study and others

(13,

31), they are likely to appear more similar to the general population of individuals with schizophrenia than if they were recruited as parents transmitting a 22q11.2 deletion to affected offspring

(4). Inclusion in previous studies of substantial proportions of patients with mental retardation

(4) may also have played a role, although we found no significant differences in the schizophrenia phenotype between patients with and without mental retardation in our study.

Our results also support previous work

(4) indicating that mood disturbances (in the form of major mood episodes as part of schizoaffective disorder) or symptoms (as indicated by the anxiety-depression Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale symptom grouping) do not play a major role in the majority of individuals with 22qDS-schizophrenia. The more severe excitement/impulsivity features in 22qDS-schizophrenia may be auxiliary neurobehavioral characteristics of 22qDS, possibly associated with temper or emotional outbursts in the syndrome

(5). Low lifetime comorbidity with substance use disorders and low marital and employment rates in 22qDS-schizophrenia may be related in part to the presence of congenital cardiac or other physical or cognitive features of the syndrome, younger age, and/or lifestyle differences between individuals with 22qDS-schizophrenia and other forms of schizophrenia.

Advantages and Limitations

The current study has several advantages over previous studies. To our knowledge, this is the largest group of patients with 22qDS-schizophrenia reported. There was no ascertainment bias with respect to recruiting transmitting parents, usually the largest group of adults with 22qDS in studies

(4,

15), which potentially biases to health and reproductive fitness. However, there are also several potential limitations in the study. The comparison group used was a familial schizophrenia sample. Others have used such comparison groups

(4), and we have previously demonstrated the similarity of our familial sample to other schizophrenia groups with respect to symptoms, functioning, and age at onset

(16). The main difference with such a sample is that the sex ratio is closer to 50:50 and the age at onset more similar between the sexes than in other schizophrenia groups

(16,

17).

The familial group we ascertained, however, is a community-based sample with a more representative range of IQ than many university-based research samples of schizophrenia. This likely contributed to the similarity in educational level and MMSE scores of the comparison and 22qDS-schizophrenia groups. IQ results were not available for the comparison group, and IQ testing of the 22qDS-schizophrenia patients was performed after onset of schizophrenia and may have been higher premorbidly, with more patients in the average range. The numbers of subjects in the subgroups with and without mental retardation in the 22qDS-schizophrenia group were small, and this may have limited the ability to detect statistically significant differences between these two subgroups. A schizophrenia comparison group where one-third of the subjects had a dual diagnosis of mental retardation and schizophrenia would have allowed for inclusion of both group and mental retardation in regression analyses using all 24 22qDS-schizophrenia patients. However, comparisons between the eight 22qDS-schizophrenia patients with and the 16 without mental retardation suggested that differences would be in variables related to intellect (e.g., cognitive symptoms), not schizophrenia.

The comparison subjects were not tested for a 22q11.2 deletion; however, there was no evidence of linkage to the 22q11.2 region in this group

(17), and most 22q11.2 deletions result from spontaneous mutations

(9,

10). Therefore, familial schizophrenia samples are less likely than other schizophrenia samples to have 22q11.2 deletions. Neither treatment response nor the length of the chromosome 22q11.2 deletion would appear likely to have affected results of the current study; these important variables will be reported separately.

22qDS-Schizophrenia as an Etiologic Subtype of Schizophrenia

This study and others

(4,

13,

31) support 22qDS as a true etiologic subtype of schizophrenia, identifiable by its associated physical and cognitive features and chromosomal abnormality. On the other hand, 22qDS-schizophrenia without mental retardation does not appear to represent a clinical subtype of schizophrenia in terms of the core clinical schizophrenia phenotype. In etiologic subtypes of an illness the basic condition is the same, although clinical nuances may be discernible. Subtypes based on etiology can facilitate identification of contributory genes and improve understanding of the pathophysiology of the condition as a whole. For example, a parallel may be drawn between psychotic disorders, the most common of which is schizophrenia, and dementias, the most common of which is Alzheimer’s disease. There are several etiologic subtypes of Alzheimer’s disease

(32). One of these is associated with mutations of the beta amyloid precursor protein gene (βAPP) on chromosome 21

(33). Alzheimer’s disease found in Down’s syndrome (trisomy chromosome 21), a possible familial association between Alzheimer’s disease and Down’s syndrome

(34), and the localization of the βAPP gene near the key region of chromosome 21 associated with the Down’s phenotype

(35) preceded the determination that βAPP plays a role in some forms of Alzheimer’s disease. In Alzheimer’s disease as a whole, the Alzheimer’s disease associated with Down’s syndrome is rare, and βAPP mutations are a rare cause of familial Alzheimer’s disease. However, the related molecular discoveries have contributed to a greater understanding of the pathophysiology of Alzheimer’s disease in general

(32). There are no comparable mutations yet identified for schizophrenia. However, establishing 22qDS as an identifiable subtype of schizophrenia may help lead to corresponding molecular genetic discoveries and subsequent neurobiological insights.

Etiologic categorizing differs from the clinical subtyping of schizophrenia familiar to psychiatric clinicians (e.g., paranoid and disorganized subtypes). It also differs from that found in Davison and Bagley’s review of schizophrenia-like psychoses

(36). This classic review included conditions in which psychosis dominated the clinical picture, as well as those with more complete schizophrenia-like syndromes, and conceptualized these as “phenocopies” associated with a variety of causes. In contrast, our conceptualization of a 22qDS subtype of schizophrenia is that, similar to other genetic forms of schizophrenia

(17), the 22q11.2 deletion is likely to be one of multiple possible genetic predispositions to the neurodevelopmental changes that could lead to expression of schizophrenia and related disorders

(2). We have found similar structural brain abnormalities in 22qDS-schizophrenia as those commonly seen in schizophrenia without 22qDS

(37), supporting the likelihood that a 22qDS subtype of schizophrenia may share some aspects of a general pathogenetic pathway for schizophrenia.

Neurobehavioral Phenotype of 22qDS

The focus in this study is 22qDS-schizophrenia in adults, but there is a complex neurobehavioral phenotype of 22qDS that is likely to be as variable as the physical phenotype. Cognitive abnormalities are the most prevalent aspect of the neurobehavioral phenotype, ranging from average intellect with minimal learning difficulties to severe deficits

(8). Children and adults with 22qDS may have psychiatric disorders other than schizophrenia that meet standardized diagnostic criteria, such as anxiety disorders, mood disorders, and attention deficit disorder. There is no evidence as yet that rates of these other disorders are higher than expected in the general population for a given intellectual level

(38) or for individuals at elevated genetic risk for schizophrenia. It is likely, however, that there are other aspects of neurobehavior in 22qDS that do not fit a diagnostic category

(38), such as impulsivity and emotional outbursts

(5,

39). Results of the current study suggest that these other neurobehavioral features may color the presentation of major illnesses without necessarily affecting the core diagnostic phenotype.

22qDS in Research on Schizophrenia

Results from this study indicate that physical and intellectual phenotypic features

(3) will remain the primary means of identifying a 22qDS subtype of schizophrenia. However, it is apparent from this study and others

(4,

15,

31) that many individuals with 22qDS-schizophrenia will not have obvious congenital anomalies and that the majority of such individuals will not have mental retardation, although learning difficulties may be prevalent. This is consistent with the fact that individuals with 22qDS-schizophrenia have been recruited into research samples despite intensive prescreening, as illustrated by the National Institute of Mental Health study of childhood-onset schizophrenia

(31). Lower rates of comorbid substance use disorders may further facilitate the potential inclusion of subjects with 22qDS-schizophrenia in research studies of schizophrenia. A high index of suspicion, careful medical history taking, and assessment for the more subtle physical and cognitive features of the syndrome will often be necessary to identify subjects with 22qDS

(3,

6,

9). Separate study of these individuals will be important to determine which features distinguish this etiologic subtype from other forms of schizophrenia.

Summary

The results of this study support the potential for 22qDS-schizophrenia as an appropriate model for schizophrenia and as an etiologic subtype of the illness. The greater homogeneity of groups of subjects with 22qDS-schizophrenia compared with general population groups of subjects with schizophrenia should be helpful in learning more about the neurodevelopmental pathogenesis of schizophrenia, particularly with respect to the genetic and nongenetic factors contributing to expression of the illness

(2). There do not appear to be major clinical differences in the core schizophrenia phenotype, and this provides further support for prospective studies of young individuals with 22qDS for onset of schizophrenia.