Inpatient Studies

More recent inpatient studies clearly enhance the internal validity of the evidence for a cannabis withdrawal syndrome. In a 1999 study by Haney et al.

(30), 12 heavy marijuana smokers (mean of 4 joints/day) received placebo pills on study days 1–3, 8–11, and 16–19; 20 mg of oral THC four times a day on days 4–7; and 30 mg of oral THC four times a day on days 12–15. Compared to the placebo baseline phase, abstinence from THC (i.e., placebo periods after THC use) was associated with significantly increased ratings of anxiety, depression, and irritability; decreased ratings of quantity and quality of sleep; and decreased food intake. Systematic relations between the THC dose and the magnitude of abstinence effects were not generally observed, although increased anxiety and restlessness were reported only after the higher dose.

A similar study, again with daily marijuana smokers, tested for abstinence effects after cessation of two doses (THC concentrations of 1.8% and 3.1%, respectively) of smoked marijuana cigarettes

(31). Both doses were administered four times per study day. Results paralleled those reported in the oral THC study. Abstinence increased ratings of irritability, anxiety, and stomach pain; decreased ratings of contentment, friendliness, talkativeness, sociability, and energy; and also decreased food intake. No robust abstinence effects on social behavior or performance were observed. In contrast to the oral THC study, this study of marijuana smokers did not report sleep disturbance during the abstinence phases. Clear dose-related differences in abstinence effects were not observed. Most mood symptoms peaked on day 3 or 4 of the abstinence phases.

A third similarly designed study compared the effects of smoked marijuana and oral THC

(32). Abstinence effects were observed for smoked marijuana but not for oral THC. Failure to observe abstinence effects from oral THC may have been due to use of a lower dose of oral THC and the shorter durations of drug administration and abstinence periods, compared with previous oral THC studies. Last, as documented in

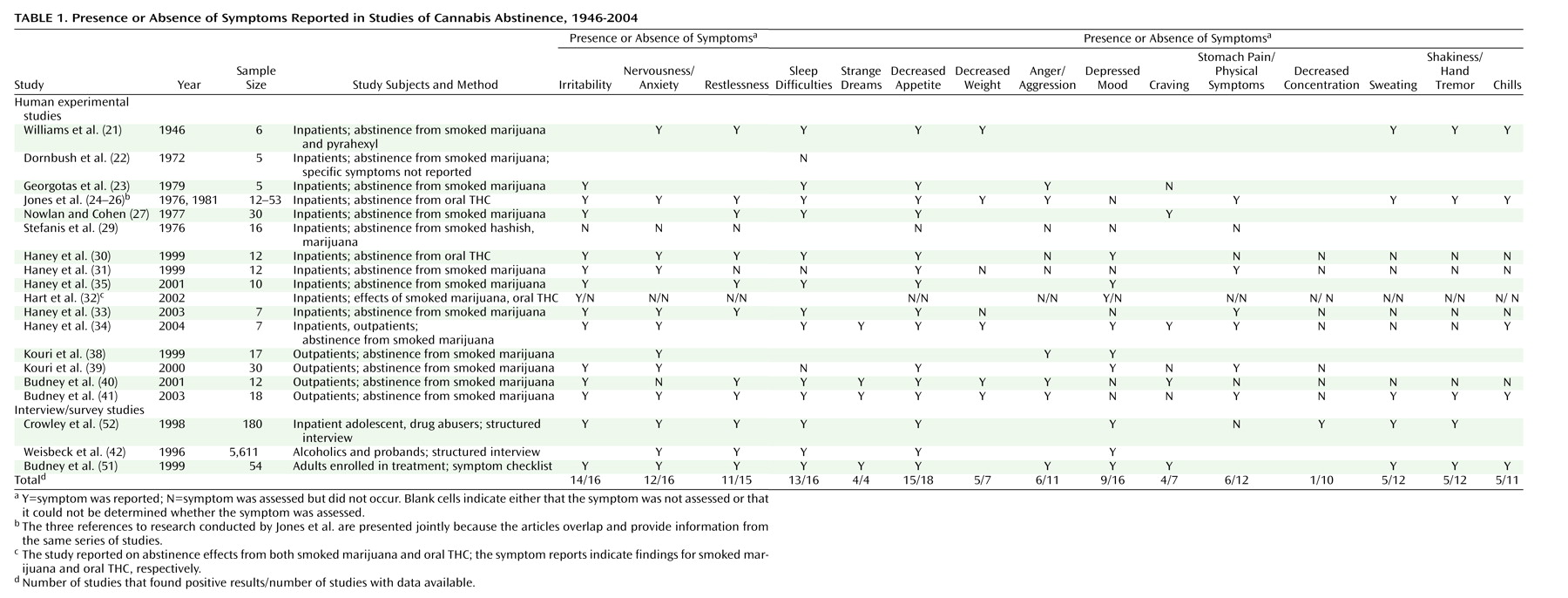

Table 1, abstinence effects after cessation of smoked marijuana were replicated under placebo conditions in three other inpatient studies designed to test the effect of medications on marijuana abstinence symptoms

(33–

35). In summary, several well-controlled inpatient studies repeatedly confirmed that abstinence effects such as irritability, weight loss, and sleep difficulty occur reliably. It is noteworthy that these studies controlled for potential confounders by using placebo conditions and excluding persons who abused other substances, had an active psychiatric disorder, or were taking psychoactive medication.

Outpatient Studies

Outpatient studies are important because inpatient studies do not include many of the environmental stimuli (e.g., persons or things associated with smoking) that can produce conditioned withdrawal effects, and thus inpatient studies may underestimate the severity of drug withdrawal

(36,

37). An initial outpatient study

(38) examined aggression during a 28-day period of verified cannabis abstinence using a novel laboratory analog test of provoked aggression with chronic (daily) marijuana smokers who did not abuse other substances, did not have a current psychiatric condition, and did not take psychoactive medication. Greater levels of aggression were observed on days 3 and 7 of abstinence, compared with day 0 (baseline). This increased aggression abated by day 28, showing that this effect was transient. These daily marijuana smokers made significantly more aggressive responses than a comparison group of 20 former or infrequent marijuana smokers.

This outpatient study and the aforementioned inpatient and animal studies were available at the time of Smith’s review

(5), discussed earlier. Thus, although robust findings from animal and inpatient studies and suggestive data from outpatient studies were available, what was lacking at the time of the prior review were comprehensive prospective studies with adequate baseline data, demonstrations of clinically significant symptoms, and a clear delineation of the time course of withdrawal. Since that review, three additional rigorous outpatient studies have been reported that we believe provide these elements.

A more comprehensive outpatient study

(39) of cannabis withdrawal compared current daily cannabis smokers (same inclusion/exclusion criteria as the aforementioned study

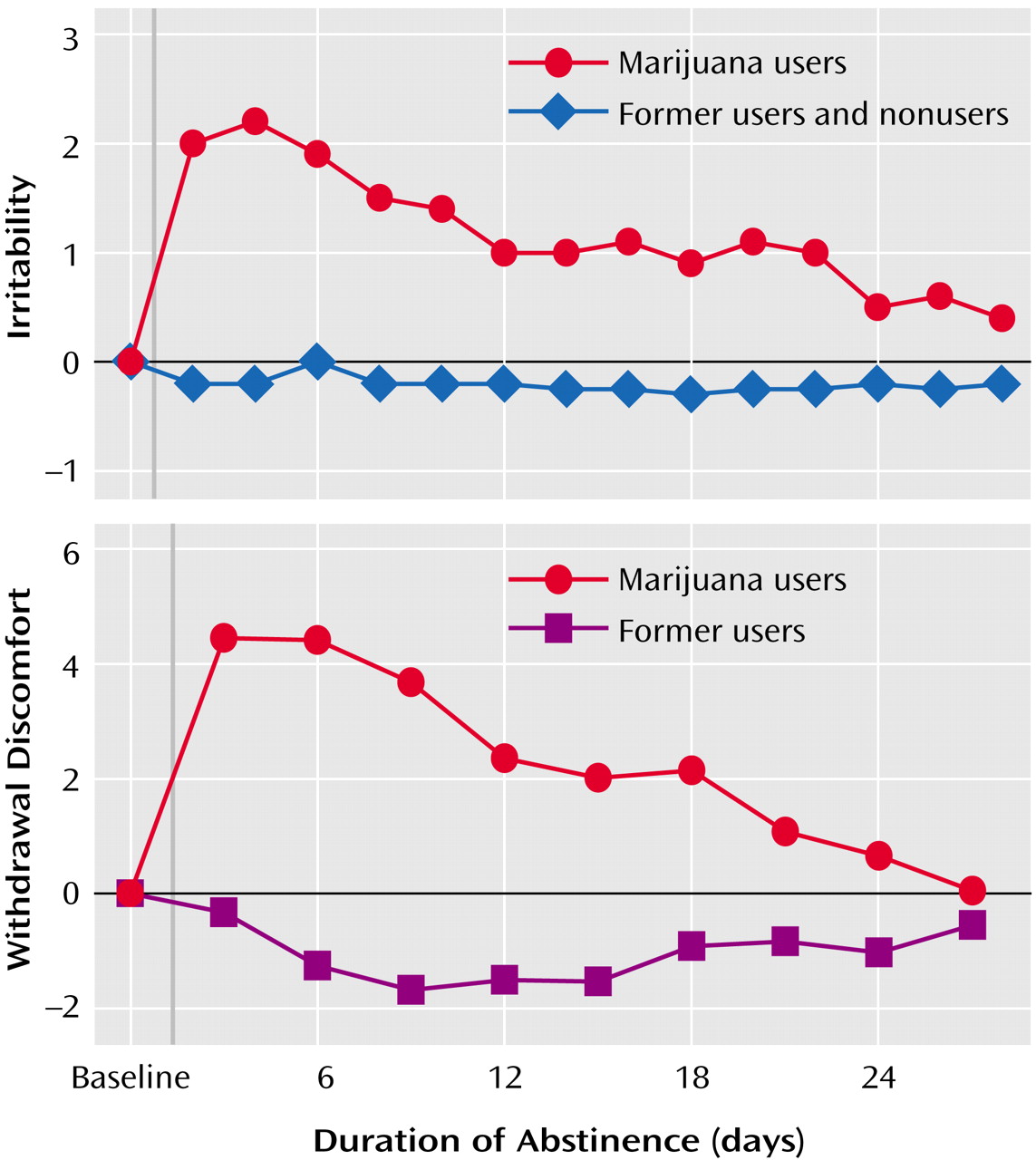

[38]), former cannabis smokers, and nonusers during a 28-day period of verified abstinence. A prewithdrawal baseline was estimated with a single retrospective rating of 14 symptoms over the past 6 months. Among the daily users, appetite was decreased (compared with baseline) on days 1–9 of abstinence, anxiety was higher on days 1–11, irritability was greater on days 1–14, mood was lower on days 3 and 9, physical tension was greater on days 1–10, and physical symptoms were greater on days 1–8, 10–13, 15–18, and 27. The daily users showed greater levels of anxiety, irritability, negative mood, physical symptoms, and decreased appetite during the abstinence period but not at baseline, compared with the two comparison groups. Hamilton Depression Rating Scale and Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale scores of the daily users were also greater than the comparison-group scores on days 1 and 7 of abstinence but not on day 28. The daily users’ levels of irritability (

Figure 1) and physical tension remained significantly elevated above the comparison groups’ levels throughout the entire 28-day study. As such, whether these two symptoms are true withdrawal symptoms rather than offset effects is unclear. Interpretation of these results is somewhat limited by the single retrospective baseline measure. Thus, the true magnitude of the observed abstinence symptoms and the time of offset are difficult to discern. Nonetheless, the systematic changes in symptom scores during the abstinence period and the systematic differences over time between the users and the comparison groups suggest that these findings reflect reliable cannabis withdrawal effects.

A third outpatient study

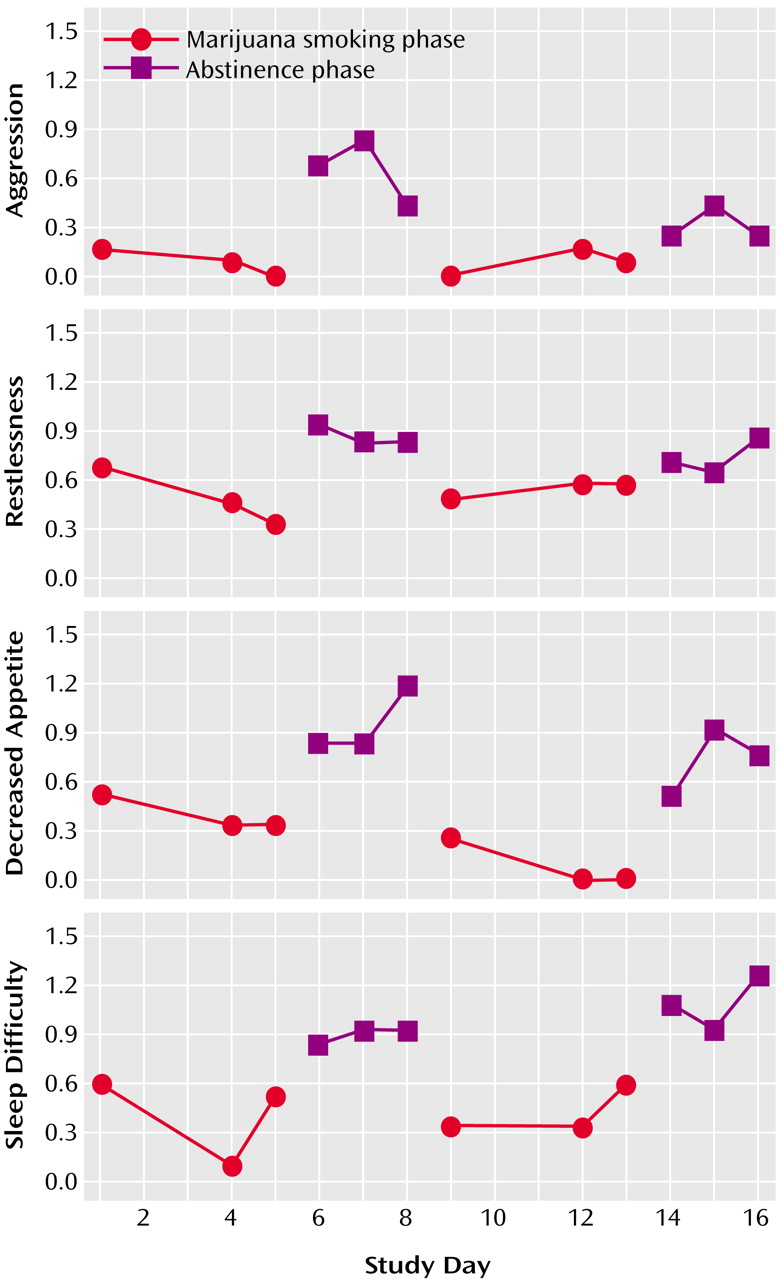

(40) collected daily prospective baseline measures and thus remediated the problem of the prior outpatient study. Twelve daily marijuana smokers (who used marijuana an average of 3.6 times/day and did not use other illicit drugs, abuse alcohol, have an axis I psychiatric disorder, or take psychoactive medication) provided self-ratings of withdrawal discomfort on 16 consecutive days during which they smoked marijuana as usual (days 1–5, or the baseline period), abstained from smoking (days 6–8), returned to smoking (days 9–13), and again abstained (days 14–16). Overall withdrawal discomfort increased significantly during the two abstinence phases, compared to the original baseline period, and returned to baseline when marijuana smoking resumed during the third phase (

Figure 2). Craving for marijuana, decreased appetite, sleep difficulty, and weight loss reliably changed across each smoking and abstinence phase. Aggression, anger, irritability, restlessness, and strange dreams increased during both abstinence phases, but the effect was statistically significant only in the first abstinence phase. Onset for most abstinence symptoms occurred within 48 hours of cessation. Telephone interviews with collateral observers living with the participants confirmed participants’ reports of increased irritability, aggression, and restlessness during abstinence. In summary, these test-retest results demonstrated the within-subject reliability and internal validity of marijuana abstinence effects in an outpatient setting. In addition, the validation of symptoms by home-based observers suggested that the effects were of a clinically significant magnitude. This study clearly established time of onset of most symptoms, but the short cessation period (3 days) limited examination of duration and peak effects.

A fourth study replicated and extended these findings

(41). This 50-day study assessed 18 daily cannabis users (same inclusion/exclusion criteria as the prior study) during a 5-day baseline (smoking as usual) period and a 45-day cannabis abstinence period. A comparison group of 11 former cannabis smokers was used to assist with interpretation of findings. The effects and symptoms that changed significantly from baseline during the abstinence period were almost identical to those in the prior study and included anger and aggression, decreased appetite, irritability, nervousness, restlessness, shakiness, sleep difficulty, stomach pain, strange dreams, sweating, and weight loss. The onset of most effects occurred between days 1 and 3. The time of peak severity occurred between days 2 and 6, with most symptoms peaking around day 4 (

Figure 1). Effect sizes for each symptom were in the medium to large range. Most effects were transient, i.e., returned to baseline levels by the end of second week of abstinence, although strange dreams and sleep difficulties showed significant elevations throughout the study. All effects, with the exception of sleep difficulties and craving for marijuana, returned to the level observed in the comparison group of former users. Again, collateral observers confirmed reports of aggression, irritability, restlessness, and sleep difficulty. In summary, this study documented 1) the time course of withdrawal, 2) the substantial magnitude of symptoms, and 3) the transience of most symptoms. In addition, the observation that most symptoms returned to baseline levels and to the level observed in the former users (with absolute symptom values approximating zero) suggests that these findings were not rebound effects indicative of symptoms that existed before the use of cannabis.

The results of these four controlled outpatient studies are remarkably consistent and provide validity for a cannabis abstinence syndrome. The generalizability of these studies is limited because the inclusion of only daily users likely produced more severe symptoms than if light or nondaily users were studied. On the other hand, all four studies excluded treatment seekers, persons with significant psychiatric disorder, and persons who used other substances or abused alcohol. Exclusion of such participants likely resulted in less severe withdrawal symptoms than might have been observed if such participants were included

(7).

Survey Studies

Although survey studies cannot provide empirical demonstration of the validity of an abstinence syndrome, they can provide real-world replications of experimental trials and estimates of how common marijuana withdrawal is. Structured interviews from the Collaborative Study of the Genetics of Alcoholism sample indicated that 16% of those with a lifetime history of regular cannabis use (>21 times/year) described a lifetime history of cannabis withdrawal, i.e., reported at least two symptoms from a seven-item withdrawal checklist

(42,

43). Among those who also met the criteria for a lifetime cannabis dependence diagnosis, 40% reported symptoms of withdrawal. In the DSM-IV field trials, 25% of persons who had smoked cannabis at least six times in their life reported experiencing cannabis withdrawal in the past; however, specific symptoms were not defined

(44). An Australian study indicated that 20%–25% of long-term cannabis users (use three to four times per week for at least 10 years) in the general population responded affirmatively to an ICD-10 or DSM-III-R dependence criteria question on withdrawal

(45). In a second Australian study of long-term cannabis users (weekly use for at least 3 years), 32% responded affirmatively to a 12-month ICD-10 dependence criteria question on cannabis withdrawal

(46).

Across studies of adults seeking treatment for cannabis abuse/dependence, 51%–95% reported cannabis withdrawal during the past year in structured diagnostic interviews

(47–

50). In the only study that inquired about specific withdrawal symptoms in adults seeking treatment for cannabis dependence

(51), 85% reported experiencing at least four symptoms of at least mild severity the last time they abstained from cannabis for at least 24 hours. The most frequently reported symptoms (reported by more than 70% of the sample) were cravings, irritability, nervousness, depressed mood, restlessness, sleep difficulty, and anger. It is noteworthy that 67% rated four or more symptoms as moderately severe and 47% rated four or more symptoms as severe, the highest category on the 4-point scale. In the only study of adolescents, 67% of a group in residential care for drug abuse described a history of cannabis withdrawal, with the most common symptoms being irritability, restlessness, depressed mood, sleep difficulty, and fatigue/yawning

(52).

These survey studies all relied on retrospective reports, did not control for symptoms experienced during regular cannabis-use periods (baseline), and did not discern whether the participants had stopped any other substance use simultaneous with the referent period of cannabis cessation. Thus, the validity and causality of the symptom reports cannot be clearly established. Nonetheless, the symptom profiles reported in these studies are remarkably similar to those reported in the experimental studies reviewed earlier, providing convergent validity for the syndrome. The consistency of these survey findings strongly suggests that cannabis withdrawal occurs among a substantial subset of regular marijuana users who stop smoking cannabis, and, most likely, the prevalence of such withdrawal is greater among heavier users and particularly among those seeking treatment for cannabis dependence.