Studies in the United States indicate that less than half of all terminally ill patients who are eligible for hospice services receive hospice care

(1,

2). Furthermore, many patients who do receive hospice care enroll late in the course of their illness

(3–

5). Medicare data from 1990 indicate that the median enrollment time is only 36 days, with more than 15% dying within 7 days of enrollment

(4). The U.S. General Accounting Office has recorded substantial decreases in the average length of hospice enrollment before death during the last decade

(6), and the phenomenon of limited lengths of hospice enrollment is also apparent in countries other than the United States

(7,

8). Experts in palliative care have suggested that decreasing lengths of enrollment in a hospice may have negative effects on patients and their family caregivers; however, limited empirical data exist to evaluate this claim. Previous studies have found greater caregiver satisfaction

(9–

12) and reduced caregiver anxiety

(12–

14) for those whose loved one received hospice compared to conventional care. However, we know of no published studies that compare caregiver outcomes based on the length of hospice enrollment among hospice users.

The objective of our study was to assess the impact of length of hospice enrollment on caregiver major depressive disorder—a disabling and costly yet treatable disease—among recently bereaved caregivers. We hypothesized that caregivers of patients with fewer days of hospice enrollment would be at a heightened risk of a subsequent major depressive disorder. Evidence of a relationship between length of hospice enrollment and subsequent major depressive disorder of the surviving caregiver might identify a target group for whom bereavement services may be most needed as well as encourage earlier initiation of hospice treatment for appropriate patients.

Method

Study Design and Group

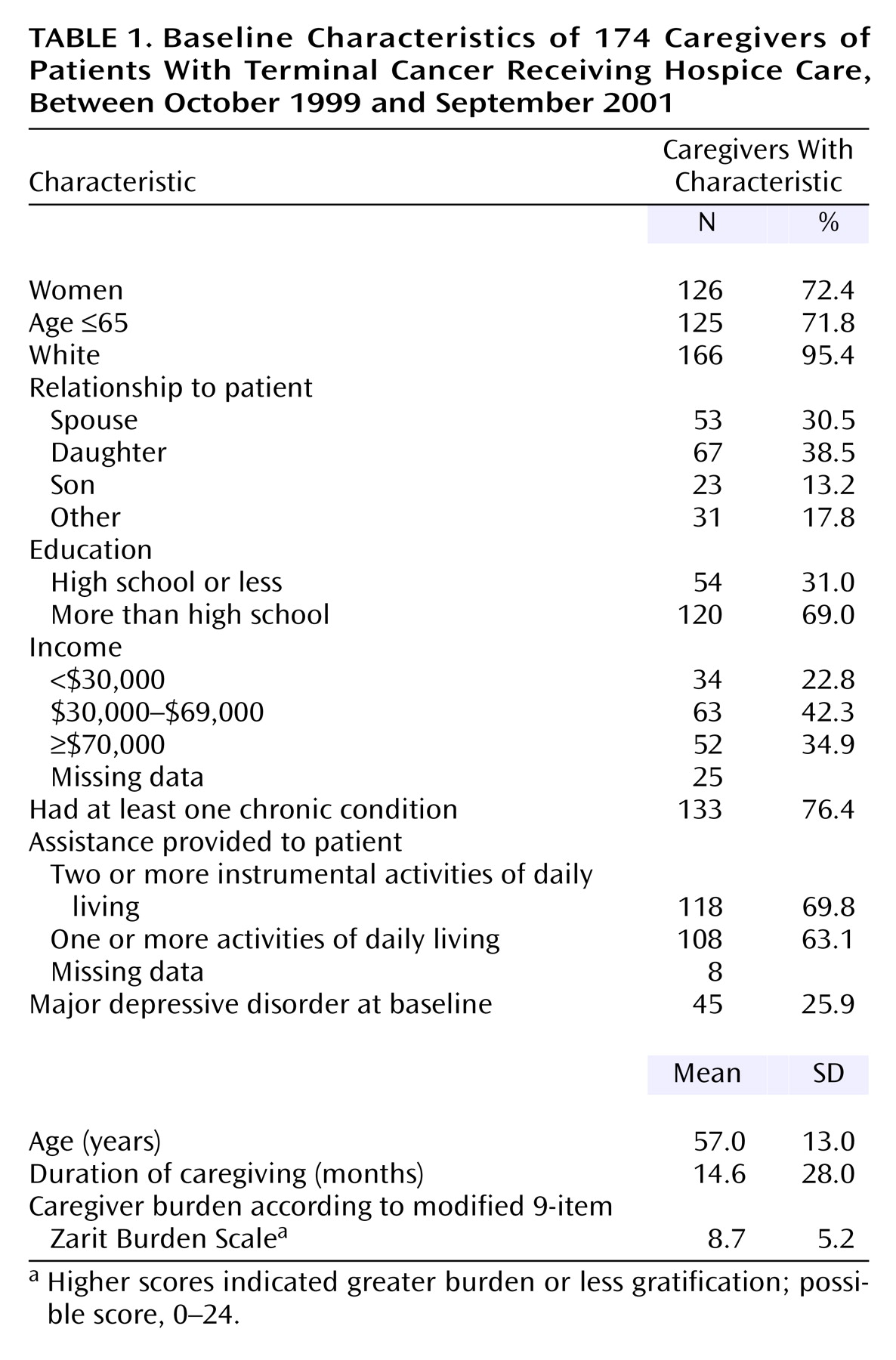

We conducted a prospective longitudinal study of 174 primary family caregivers of terminally ill adult patients with cancer who were consecutively enrolled between October 1999 and September 2001 in the largest hospice facility in Connecticut. Primary family caregivers were those whom the hospice nursing staff identified as providing the most care and planning for the terminally ill patients.

During the enrollment period, 391 caregivers were approached for participation in the study by a hospice staff research liaison. Of the 391, 100 caregivers indicated that they did not want to be contacted by researchers. Of the remaining 291, 28 could not be contacted because of incorrect or unlisted telephone numbers and addresses, 51 refused to participate, and six were too ill or cognitively impaired to participate in the study. Thus, the study group at baseline was 206 caregivers, which was 53% of the 391 caregivers originally approached, for an 81% participation rate of those contacted by researchers (51 refusers of 263 caregivers contacted). All participants provided their written informed consent to participate, using procedures approved by the institutional review boards of the Yale School of Medicine and of the hospice organization where the study was conducted. In chi-square and t test analyses, no significant differences in gender distribution, kinship relationship to the patient, or number of days enrolled in a hospice were apparent between the caregiver participants and nonparticipants.

Of the 206 caregivers participating in the initial phase of the study, 203 were eligible for interviews approximately 6 months after the patient’s death. In three instances, the patient did not die within 1 year after the initial hospice enrollment, thus, the caregivers were not eligible for the follow-up interview; 25 refused to participate (mostly because of time constraints), two were too ill to participate, and two could not be contacted after repeated attempts. Thus, the final group size was 174 caregivers, or 85.7% of 203 eligible respondents who completed the baseline interview. Based on chi-square and t test analyses, the caregivers who refused to participate at this stage did not differ from those who participated in terms of gender distribution, kinship relationship to the patient, prevalence of baseline major depressive disorder, and the number of days the patient was enrolled in a hospice.

Data Collection

Baseline interviews with caregivers were conducted face to face and were attempted before the death of the patient; however, this was not always possible. The caregivers of 76 patients were interviewed before the death of the patient, and 130 were interviewed within the month after the death. Follow-up interviews were arranged by telephone and attempted in person 6–8 months after the patient’s death. Both baseline and follow-up interviews were conducted at the location where the caregiver indicated that he or she would be most comfortable, typically either at the hospice or at home.

Measurements

The primary outcome was major depressive disorder, which was assessed at both the baseline and follow-up interviews with the major depressive disorder module of the Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM-IV (SCID) axis I modules

(15). The SCID is a widely used instrument for establishing psychiatric diagnosis, with well-established reliability and adequate validity

(16). Both at baseline and follow-up, we assessed the current prevalence of major depressive disorder. All interviews were conducted by a master’s-level prepared social worker with extensive experience in administering the SCID.

The primary predictor variable was the number of days of hospice enrollment before the death. The number of days included the days enrolled with home hospice care and the days enrolled with inpatient hospice care. For the vast majority of caregivers (196 of 206 in the study), the patient died during the initial hospice enrollment, and hence, the number of days of hospice care was equal to the number of days between the initial hospice enrollment and death. For seven caregivers, the patient was discharged from the initial hospice enrollment while alive and subsequently died. For those patients, all hospice days used between the initial enrollment and death were included, even if the days were part of a second enrollment period. We reran the final model excluding these seven patients, but their exclusion did not change the results materially.

We chose to examine particularly short hospice enrollment periods because hospice staff suggested that the short enrollment times did not allow for the full services and benefits of hospice care for both families and patients. In preliminary surveys, many hospice staff perceived 3 days as inadequate time for the necessary family meetings, family and patient discussion of preferences and planning, and implementation of comprehensive hospice care. Therefore, we analyzed the total days of hospice enrollment before death as a dichotomous variable, coded as 3 or fewer days of hospice enrollment compared to longer enrollments. The sociodemographic characteristics included the caregiver’s age, gender, educational level, annual income, marital status, religiousness, and kinship relationship to the patient. Caregiver burden was assessed with a modified Zarit Burden Interview

(17), with six items to measure caregiver burden and three items to measure caregiver gratification. The duration of caregiving (in months) before hospice enrollment was self-reported at the initial interview. Social support was measured with three items: frequency of contact with close friends or family, difficulty obtaining help with daily activities (e.g., grocery shopping, cleaning, cooking), and difficulty obtaining emotional support. Self-reported measures of health were limitations in instrumental activities of daily living

(18), limitations in basic activities of daily living

(19), and the number of chronic conditions of the caregiver. We also measured service use at the baseline and follow-up interviews: days of hospital or nursing home care before hospice enrollment, the type of hospice used (home or inpatient), and the use of bereavement services after the death. At baseline, we asked the caregivers how many weeks before hospice enrollment a physician first told them that the illness could not be cured, the physician’s prognosis at that time, when they as caregivers first knew that the illness could not be cured, what they thought the prognosis was at that time, and when the caregiver first knew it was time to use hospice care.

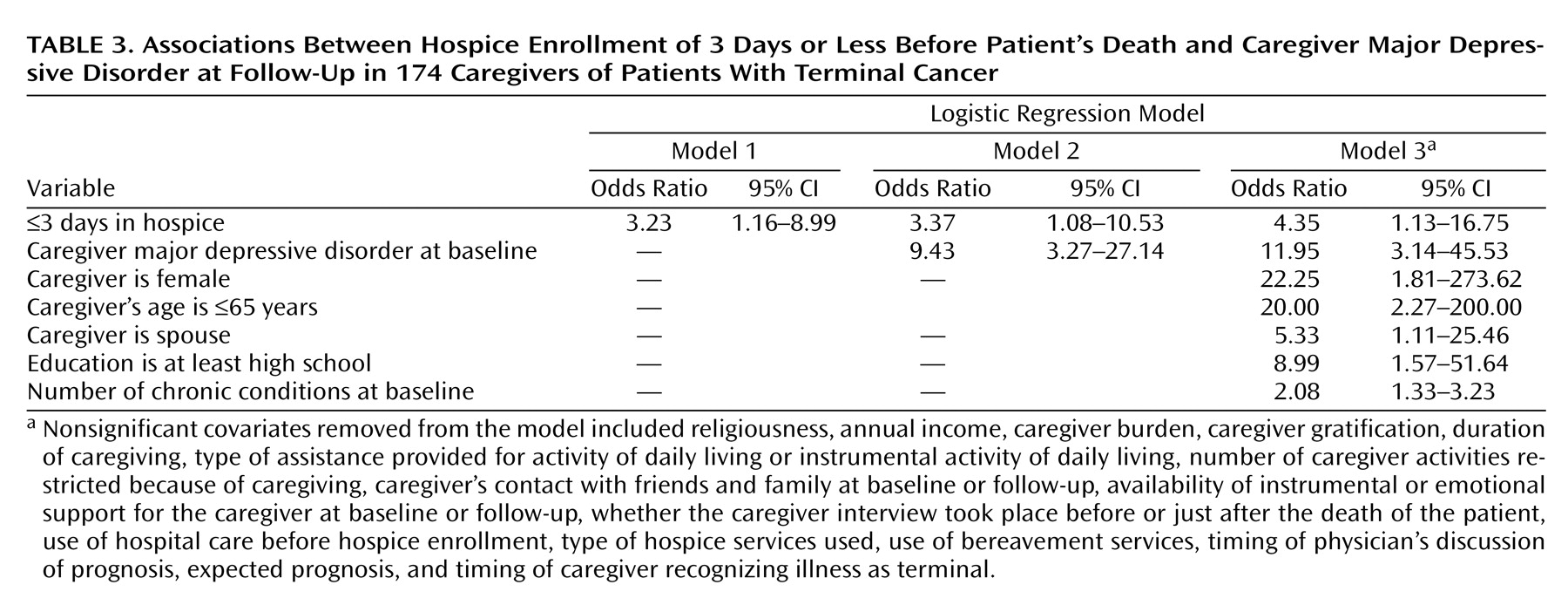

Data Analysis

We used logistic regression analysis to estimate the unadjusted associations between major depressive disorder at follow-up and having short hospice enrollment before death (3 days or fewer). We fit three logistic regression models to compare unadjusted and adjusted associations of length of hospice enrollment and major depressive disorder at follow-up. The first included only the primary independent variable of interest: 3 or fewer days of hospice care. The second model included this primary independent variable and was adjusted for baseline major depressive disorder. The third model was fully adjusted for all potential confounders ascertained. Covariates were retained in the multivariate model if their association with major depressive disorder was statistically significant (p<0.05). In general, the removed covariates not retained in the full model did not change the parameter estimate on hospice use by more than 10%, a reasonable threshold for variable selection

(20), and all had p values greater than 0.15.

Discussion

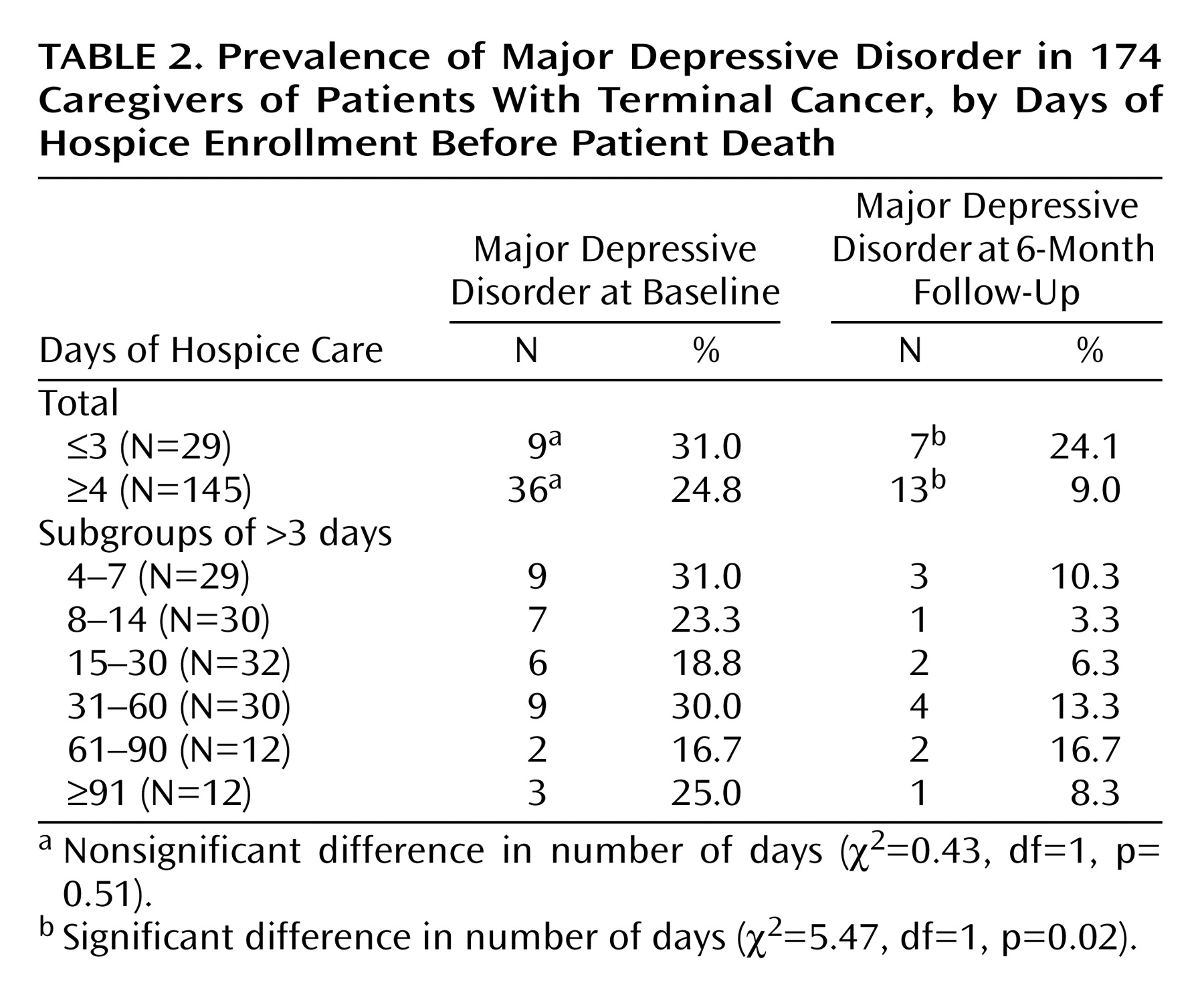

We found that a substantial proportion of patients (about 17%) enrolled with a hospice only 3 or fewer days before their death. The sizable proportion of patients with such short hospice enrollments is particularly striking because all the patients in the study had the primary diagnosis of terminal cancer, a disease with a more predictable trajectory than other common causes of death. These results are consistent with previous studies

(4–

6); however, we found an even higher proportion of patients with short hospice enrollments before death than in previous studies of Medicare beneficiaries

(4). This may be because our group included younger, non-Medicare patients and because lengths of hospice enrollment have been declining in the last decade

(6).

Caregivers of patients with few days of hospice care were at an increased risk of subsequent major depressive disorder, a debilitating and costly disease for both individual sufferers and society. In our study of 174 caregivers, 24.1% of the caregivers of patients with 3 or fewer hospice days met diagnostic criteria for major depressive disorder compared to 9.0% of the caregivers of patients with longer hospice lengths of enrollment. Some patients with major depressive disorder reflected nonrecovery from major depression at the time of enrollment; others reflected new cases of major depressive disorder during the months after the death.

The reasons for the association between length of hospice enrollment and subsequent caregiver depression are not clear. One interpretation might be that caregivers who have major depressive disorder and/or do not accept the terminal illness of the patient delay hospice enrollment. Their subsequent major depressive disorder 6–8 months after the death might therefore be due to their baseline major depressive disorder or other factors that delayed the hospice enrollment decision. However, in this study, major depressive disorder at baseline was not associated with length of hospice enrollment. Furthermore, the significant association between shorter hospice enrollments and postloss major depressive disorder persisted after we controlled for caregiver major depressive disorder at baseline and was unaffected by other correlates of hospice enrollment length, such as hospitalization before hospice enrollment, the timing of physicians’ prognostic discussions, or caregiver beliefs about prognosis.

Alternatively, many of the hospice services directed at preparing the family for the impending death, such as counseling, alleviation of pain, and spiritual care, may be abridged in cases of extremely short enrollments, such as 2 or 3 days. Research on bereavement and depression has identified a lack of preparation for death as a risk factor for postloss depression

(21), and if fewer days of hospice care is related to inadequate preparation for death, then shorter hospice enrollment might be a risk factor for elevated caregiver depression during bereavement.

The results of this article should be interpreted in light of several considerations. First, our study group was drawn from a single site, which might limit its generalizability; however, the prevalence of preloss and postloss major depressive disorder found among this group is consistent with other studies of caregivers of patients receiving hospice care

(22) and their bereavement adjustment

(23). Second, because our patient selection was from a hospice with a large inpatient component, we had a preponderance of patients who used inpatient care only. Although this in not typical in the United States, it allowed us to study in more depth the phenomenon of late hospice enrollment, which is quite common among the many patients who die in inpatient hospices annually

(24). Third, we studied only caregivers of patients with cancer. This was in part to control for the different prognostication abilities among patients with other diseases and because of the high prevalence of cancer among hospice users. However, our results may have differed for caregivers of patients with other diseases. Fourth, because these data were observational and not the results of a randomized controlled trial, we must refrain from inferring that the observed associations were causal. Finally, we assessed only major depressive disorder and not other psychiatric disorders, so we were unable to examine the influence of hospice length of enrollment on a variety of other, and potentially comorbid, conditions (e.g., anxiety and/or substance abuse disorders).

Previous studies have suggested multiple reasons that patients may receive hospice late in the course of illness. These include the imprecision of prognostication

(4,

5,

25–27), the patients’ resistance to being labeled as dying

(28) and foregoing curative care

(3), the physicians’ reluctance to initiate advance-care planning

(29) and to discuss the prognosis frankly

(3,

30,

31), reimbursement systems that separate palliative from curative care

(28,

32), and increased scrutiny of hospices’ and physicians’ compliance with the 6-month prognosis requirement

(3,

32).

These challenges to earlier hospice enrollment are substantial. However, our findings help illuminate some of the consequences for caregivers of not addressing these potential barriers to earlier hospice enrollment when appropriate. Earlier hospice enrollment may help reduce the risk of major depressive disorder during the first 6–8 months of bereavement. Furthermore, those whose loved one dies within the first days of hospice enrollment might be a target group for bereavement interventions to alleviate the risk of subsequent major depressive disorder.