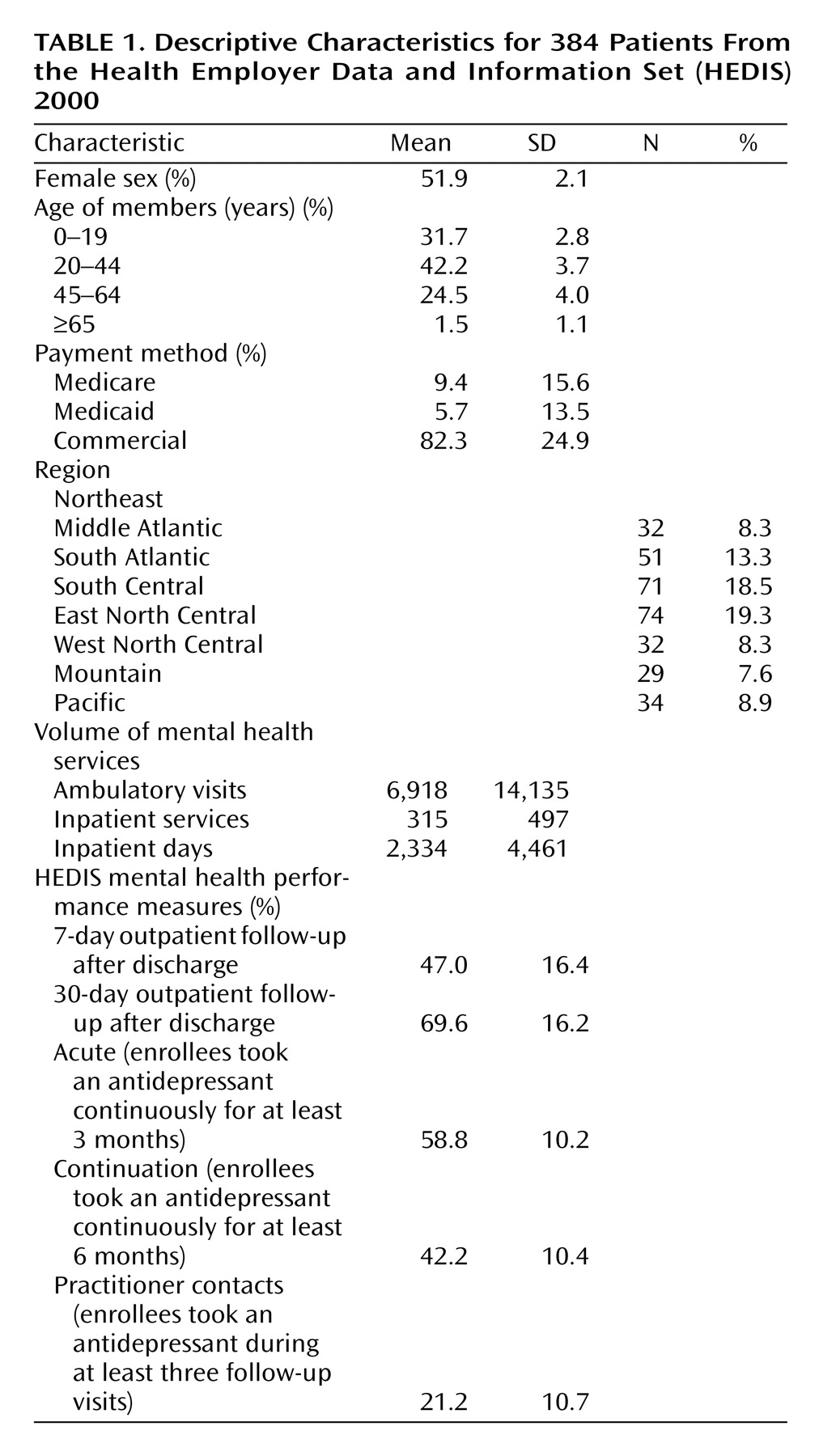

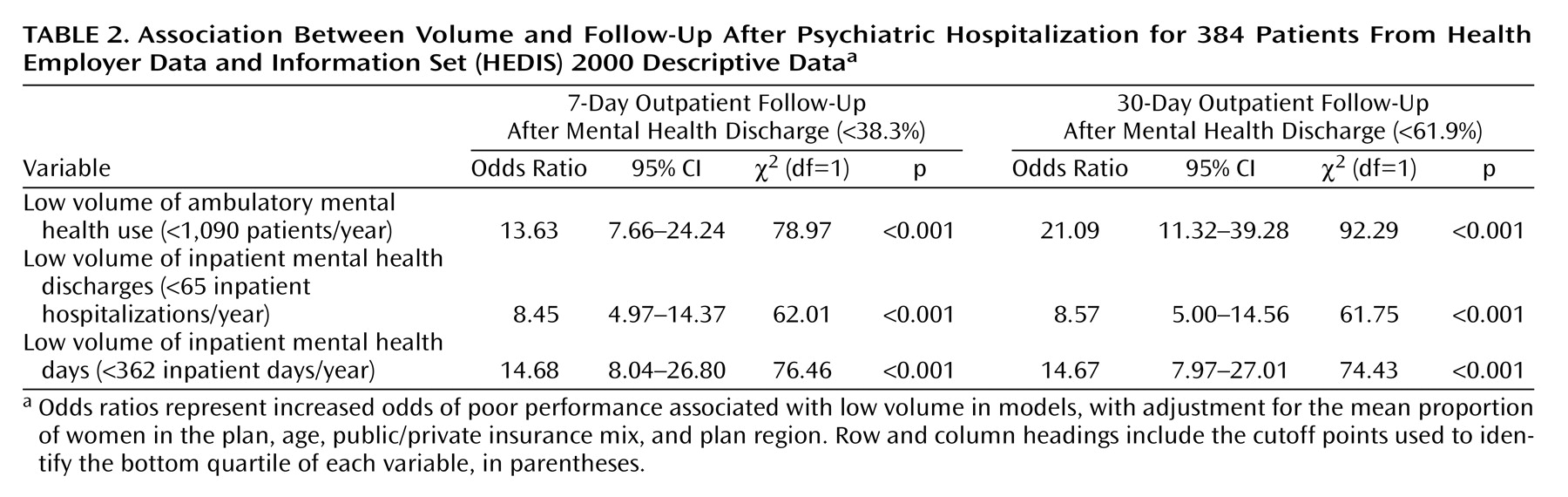

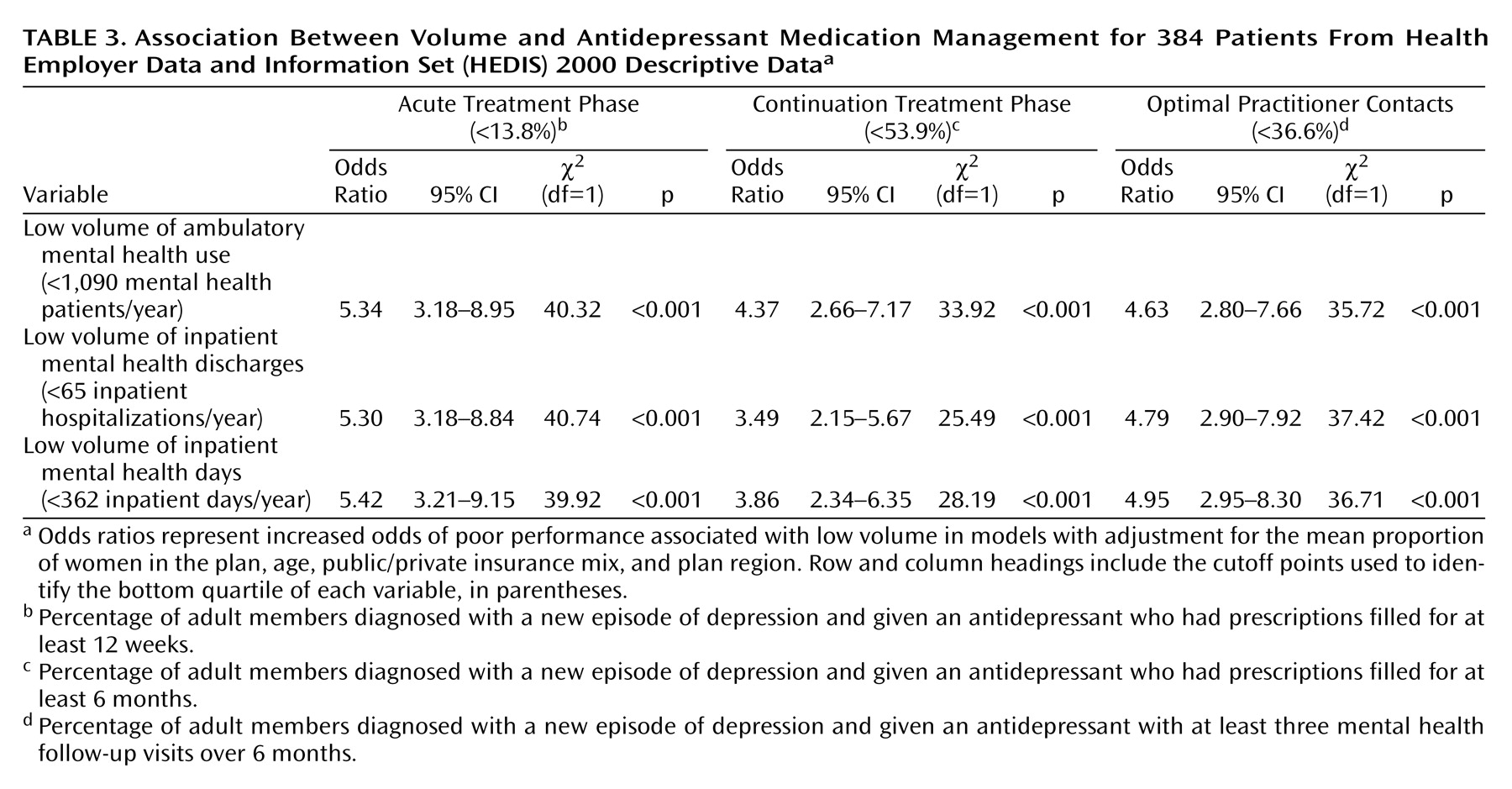

HMOs with lower inpatient and outpatient volumes of care were consistently and substantially more likely to perform poorly on the HEDIS mental health performance measures. The literature on volume and outcomes of medical care can provide a useful context for understanding the potential explanations for—and implications of—these findings.

Low Volume of Care and Poor HEDIS Performance

Two primary hypotheses have been posited for explaining the volume/outcome relationship in acute medical care—“selective referral” and “practice makes perfect”

(12). Under the first scenario, plans with a reputation for high quality of care would attract more enrollees: quality would drive volume of service delivery. Unfortunately, in today’s health market, it is relatively uncommon for purchasers and consumers to use quality indicators, particularly mental health measures, in choosing their coverage

(13,

14). Thus, while quality-based purchasing represents an important goal, it is not likely to be the primary explanation for the volume/performance association observed in this study.

The mechanism most frequently invoked as explaining the volume/outcome relationship in medical and surgical care is the notion that “practice makes perfect.” Surgeons that perform more coronary bypass operations have lower mortality rates, even after adjustment for severity of illness, likely as a result of their greater experience

(15). Intensive care units with high daily censuses are particularly successful at managing high-risk deliveries, presumably because of their ability to offer highly specialized services

(16). A recent study suggested a complex relationship between clinical-level and hospital-level volume that varies across differing procedures

(17).

One might expect that many of the same principles underlying the volume/outcomes association in medical and surgical care would apply to the delivery of mental health services. For a particular clinician, experience in interventions ranging from psychopharmacology to psychotherapy might be expected to lead to greater proficiency. Indeed, this may be one way of understanding the finding that patients treated by specialty mental health providers are more likely to receive guideline-concordant care than those treated by primary care physicians

(18). Because the current study examined only plan-level associations, it will be important for further research to examine whether these patterns are also evident at the level of individual clinicians.

For mental health organizations, there may also be benefits to specialization. Psychiatric clinics and inpatient units are often organized by diagnoses (e.g., schizophrenia) or needs (e.g., homeless clinics) to provide expertise and specialized services. A central argument for “carving out” mental health care has been that it allows for economies of scale that cannot be provided through general medical plans

(19).

However, specialization also brings potential pitfalls. Geographic consolidation of services, such as ECT, can raise barriers to access

(20); proliferation of subspecialists may lead to fragmentation

(21). The challenge facing any mental health system is how to capture the benefits of specialized, “high-volume” services while ensuring appropriate access to—and integration among—those services.

A critical issue in determining the appropriate balance between specialization and integration is what a recent Institute of Medicine report termed the “volume of what?” question

(7). For instance, it is not known how much of the volume-outcome association seen for carotid endarterectomies can be explained by experience with that particular procedure, experience in a specialized subset of those operations, or more general experience in surgical vascular procedures. In the current study, the large and consistent associations across different measures and domains suggest that the mechanisms linking volume and quality may be relatively nonspecific. Indeed, the broadest and largest associations were seen for the two measures of follow-up after hospitalization, which span both inpatient and outpatient mental health care. High inpatient or outpatient volume is likely to reflect more—and more experienced—mental health staff, as well as greater experience in administratively managing mental health care. Again, more work is needed to better delineate the precise mechanisms linking specific dimensions of volume to mental health performance.

Limitations

The study’s findings must be interpreted in the context of several limitations. Data were available only at the plan level rather than at the provider level, limiting the ability to determine how many of the observed associations reflect higher-volume clinicians or characteristics of the higher-volume plans. HEDIS performance measures are relatively crude proxies for mental health quality, covering only a limited range of domains and providing no information on clinical outcomes. Finally, the fact that both the volume measures and performance indicators rely on service use data makes it difficult to fully disentangle these two domains. Further work would benefit from the use of prospectively collected data, volume information for both providers and plans, and quality assessment that includes both process and clinical outcome measures, such as symptom profiles. It may be particularly useful to examine this relationship for more specifically defined procedures and populations, such as the case of ECT in severe depression.