Long-standing evidence suggests that those who choose medicine for a career are at greater risk for suicide: the suicide rate among physicians in the United States has been described as nearly twice that seen among white American men

(1). In a 2000 national study on causes of death, Frank et al.

(2) found a 70% higher rate of mortality due to suicide and self-inflicted injury among white male U.S. physicians than among other professionals. Female physicians’ suicide rate, however, far exceeds that of the general population, in the range of three- to fourfold

(2,

3). In a systematic review, Lindeman et al.

(4) estimated physicians’ relative suicide risk at 1.1 to 3.4 for men and 2.5 to 5.7 for women when the rates were compared with those for the general population and at 1.5 to 3.8 for men and 3.7 to 4.5 for women when the rates were compared with those for other professionals. However, the authors did not perform any quantitative summary of the results in their systematic review. Instead, they simply summarized the main results of the studies by presenting the range of the relative risks and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Furthermore, they did not perform a quantitative evaluation of publication bias and did not estimate the extent to which quality issues explained potential heterogeneity in the suicide rates in their review.

Method

Identification of Studies

We searched for studies on the rates of physicians’ mortality and suicide using electronic searches of MEDLINE (from 1966 to July 2003), PsycINFO (from 1984 to July 2003), the AARP Ageline (from 1978 to July 2003), and the EBM (Evidence-Based Medicine) Reviews: Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. “Physicians,” “doctors,” “mortality,” and “suicide” were entered as medical subject heading terms and text words and then connected through Boolean operators. We also manually searched reviews and the reference list of each article to locate additional reports published before 1966. We placed no constraints on the language in which the reports were written, the region of the study subjects’ residence, or their age group. We were careful, however, to minimize overlapping time periods and geographic regions among the included studies to avoid duplicate counting of events and the bias this can introduce into a quantitative summary of the evidence.

Our search yielded 454 studies, mainly from MEDLINE and PsycINFO. We excluded studies that did not provide any suicide numbers and those that dealt only with attitudes toward suicidal behavior or suicidal risk, suicidal tendency, suicidal thoughts, methods of suicide, physicians’ health in general, prevention of suicide, burnout and stress, experiences of family members after suicide, or therapy of suicidal doctors. We also excluded editorials, case studies, and letters on physician suicide. We included only age-standardized findings in our meta-analysis; thus, studies published before 1960 had to be excluded. Only reports about completed suicides were included; data on attempted suicides were not considered. From the remaining 32 studies we excluded those with overlapping time periods and geographic regions

(7), those dealing only with certain medical specialties

(8–

10), and those without sufficient information from which to calculate suicide rates

(11–

13). Twenty-five sets of data on physicians’ suicide rates from articles published between 1960 and July 2003 met the inclusion criteria and were entered into our meta-analysis (

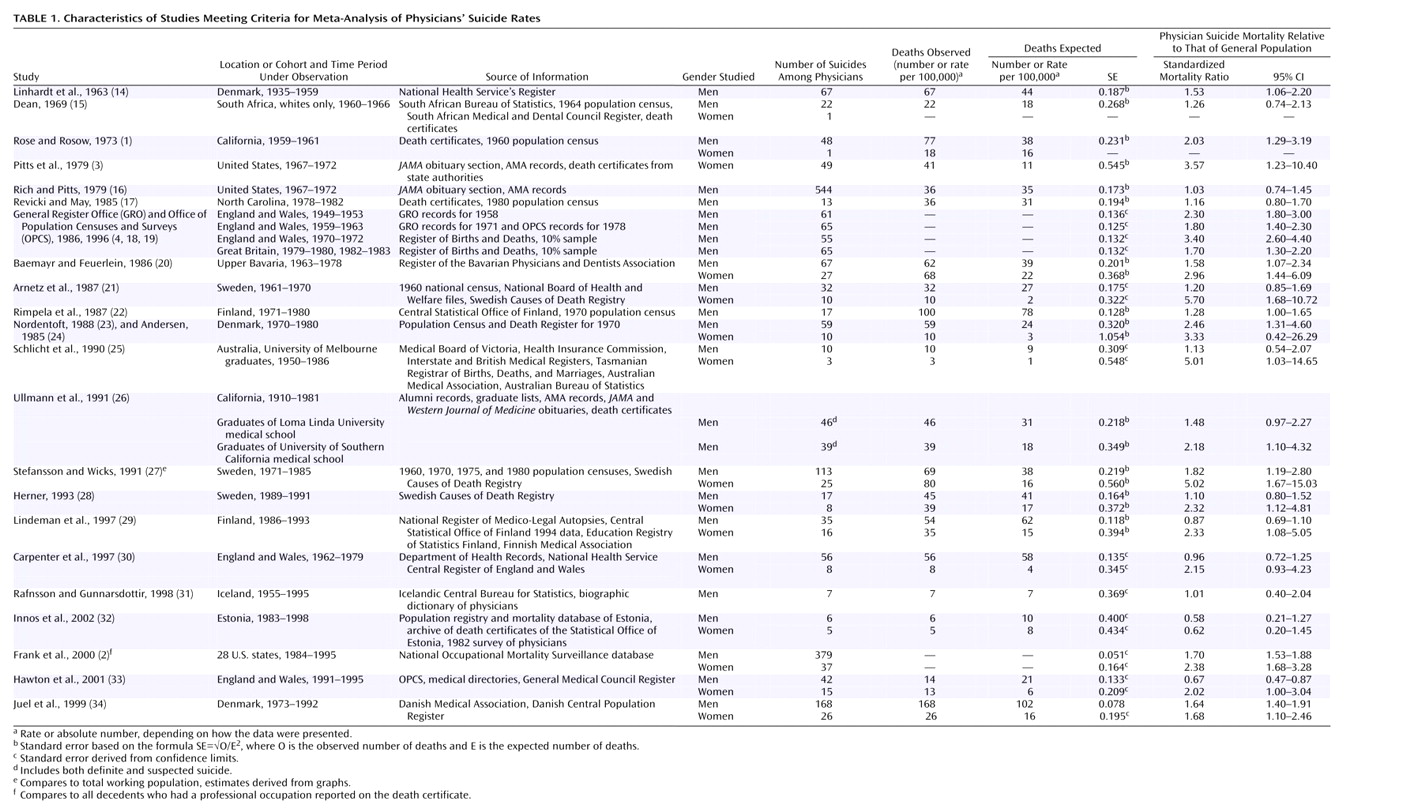

Table 1).

Data Extraction

The data extraction was done by two reviewers (including E.S.S.) using a standardized form. Where necessary, the standardized mortality ratio (SMR) was calculated on the basis of the numbers of observed (O) and expected (E) deaths reported (SMR=O/E). For one study the standardized mortality ratios had to be approximated from graphs. Standard errors were derived from confidence limits

(27). If no confidence limits were provided, we applied the formula SE=√O/E

2 to derive the standard error. We used duplicate extraction and checks for errors to ensure accuracy.

Quality Assessment Instrument

Because standard, accepted quality scales for studies on proportions, such as standardized mortality rates, are not available, we developed our own simple quality assessment instrument, to which all 25 articles were subjected. We based the design of this quality assessment instrument on some principal issues in appraising quality, similar to those for controlled trials and interventions. Specifically, we sought to address whether selection bias was minimized, follow-up for final outcomes was adequate, and misclassification bias was minimized. The same two investigators who had extracted the data independently read each article and scored the following items: check of suicides by death registers to avoid misclassification (all, some, or none of the reported suicides were checked), duration of the evaluated time period in years (>10 years, 4–10 years, 2–3 years), age standardization (standardized by using more than one age group, standardized for age >25 years only, no age standardization), and detail of reported inclusion criteria or definition of study group (very detailed, some detail, inaccurate). The quality assessment instrument was used to assign scores in the range of 0 to 2 for each of these four distinct aspects of quality, so that the potential total scores could range from 0 to 8. The simplicity of our quality scoring instrument eliminated any need to train the reviewers. Consistency in quality scores between the two reviewers reached almost 100%. Final consistency was achieved through consensus. Articles published in languages other than English or German were scored with the help of students fluent in these languages (Danish, Swedish, and Finnish). The reviewers separately reported the exact length of follow-up in each study.

Statistical Approach

We performed separate meta-analyses for male and female physicians, using the statistical software STATA

(35). We calculated rate ratios for each study and for men and women separately, on the basis of the suicide mortality rate (per 100,000 person-years) among physicians divided by the suicide mortality rate of the general population, during the time period under study. If not provided, 95% CIs were derived under the assumption of an approximate Gaussian distribution of the logarithm of the proportions. We pooled suicide rates by using a random-effects model for male doctors and a fixed-effects model for the female doctors

(36).

Because small numbers of trials limit the power of tests for publication bias, we chose to use two different tests to evaluate the possibility of publication bias among the studies. First, we conducted the Begg and Mazumdar adjusted rank correlation test for publication bias

(37) and generated a Begg plot. Second, we performed the regression asymmetry test of Egger et al.

(38) and generated an Egger plot. Significant test statistics and asymmetry in the plot, especially an empty lower right quadrant (where one would expect to find studies with small effects and high variances), suggest bias. The shape of a funnel plot is largely determined by the arbitrary choice of axes

(39). However, the standard error is likely to be the best choice for the vertical axis

(40), and we therefore chose the standard error as the measure of study size and the ratio measures for effect sizes.

Discussion

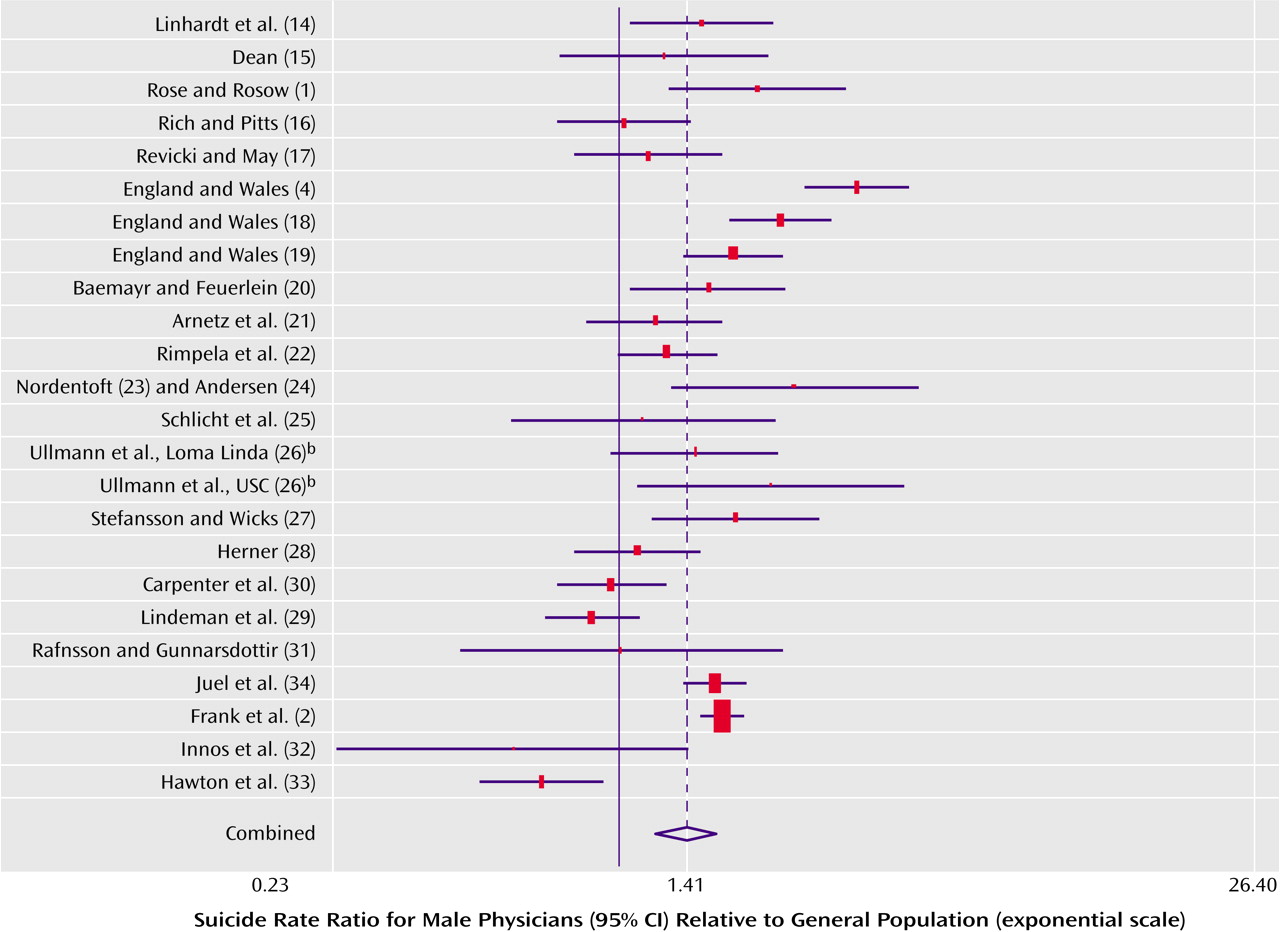

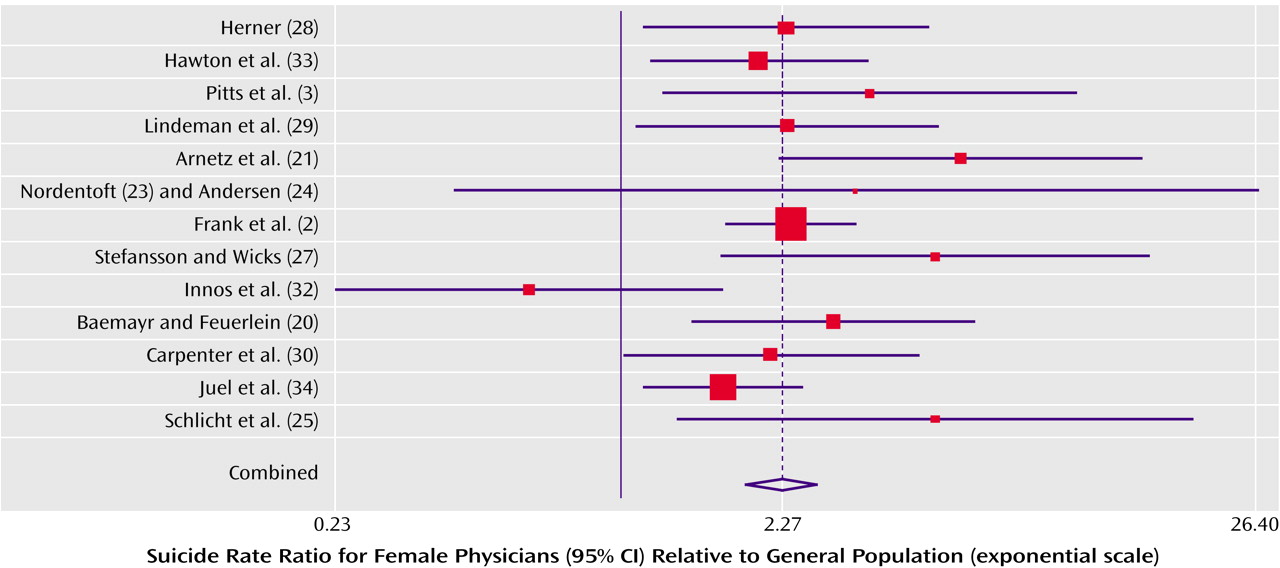

In this meta-analysis, physicians showed modestly higher (men) to much higher (women) suicide rates than the general population.

After assessment of the methodologic aspects of the studies, the results from our meta-analysis confirm previously reported physicians’ suicide rate ratios and suggest that the actual suicide rate ratio of female physicians is substantially higher than that of male physicians.

Evaluation with several methods suggests that publication bias is unlikely to have influenced the results for male physicians. However, there are other methods for testing the presence of publication bias

(41), and we cannot completely rule out publication bias, because statistical tests are generally of limited power when small numbers of studies are tested. Furthermore, although the tests we used did not suggest that publication bias influenced the results for female physicians, the visual inspection of the funnel plot revealed asymmetry. The underreporting of suicides in official statistics has been well documented

(42). Several suicides will have been recorded as open verdicts or accidents, owing to a coroner’s reluctance to enter suicide as the cause of death because of some, even minimal, doubt. Despite the fact that some studies, in response to this concern, have adopted wider definitions of suicide, such as including accidental poisoning by drugs, we kept the definition narrow in this meta-analysis. However, misclassification in the form of underreporting would bias the suicide rates only toward the null.

The limited number of female physicians is a long-standing source of concern in suicide studies. Despite the recent increase in numbers of female physicians, data on female physicians’ suicides are still few. Because small numbers have often been a major limitation in previous studies, and because even more recent studies have still had to deal with small numbers of suicides by female physicians

(2), we used meta-analysis to overcome this limitation. However, tests of publication bias indicated that only small studies of female physicians have been reported to date.

Our study population was fairly homogeneous, reflecting mainly northern European and North American countries. This limits the generalizability of our data with regard to race and sociocultural background. Another possible limitation of our analysis is that we pooled studies of varying quality. We explored study quality by performing analyses on only the trials with low quality scores and on those with high quality scores and did not observe a substantial difference in the risk of suicide among female physicians between the high-quality studies (rate ratio=2.15) and low-quality studies (rate ratio=2.71). However, our score for study quality had a limited range, indicating that study size (which was not captured by the quality score) but not the aspects that were evaluated with this instrument varied between studies.

Few authors have investigated risk factors relating to the working environment, stress factors, or specific personality traits of doctors. There has been some evidence that depression, drug abuse, and alcoholism are often associated with suicides of physicians

(43,

44). Simon

(44), for instance, reported an incidence of alcoholism and drug addiction of more than 50% among physicians admitted to psychiatric hospitals. Female physicians in particular have been shown to have a higher frequency of alcoholism than women in the general population

(45). The literature also suggests that physicians who kill themselves are more critical of others and of themselves and are more likely to blame themselves for their own illnesses

(46). Furthermore, there is some, albeit scanty, evidence that physicians feel uncomfortable in turning to colleagues for help

(47,

48) and instead resort to alcohol or drugs and isolation. Once they seek help, it appears likely that they are not taken seriously enough by their fellow colleagues: in one study it was found that among suicidal physicians who sought help, more than 50% who later committed suicide had been diagnosed with psychiatric conditions

(49) but were not hospitalized before death

(20). Finally, while the elevated rates of suicide among physicians, and in particular female physicians, may be much lower than the rates of other groups, such as elderly people or young adults of some ethnic groups, they may well be of special importance: the underlying risk factors for female physicians’ suicides seem to be more obvious

(44,

50–54), thus easier to target through prevention programs, than may be the case for other high-risk groups. For example, a higher incidence of psychiatric disorders, particularly more depression

(55), has been reported. Furthermore, additional strain imposed on female physicians by their social roles

(56), oftentimes leading to excessive drug use

(52), has been associated with suicide. However, more research is still needed to further explore these risk factors.

In light of media reports of a nationwide annual suicide toll of 30,000 Americans

(57) and the finding that suicide was the 13th leading cause of death worldwide in 2002 (ICD-10), efforts should be undertaken to target early-intervention programs at populations at high risk for suicide. We recommend the recognition of a higher risk of suicide among physicians, particularly female physicians, and the pursuit of further studies to explore potential risk factors and possible avenues of intervention. Such interventions could be modeled after a highly successful U.S. Air Force plan that made the suicide rate in the Air Force drop from 16.4 suicides per 100,000 members to 9.4 by 1998. The program was implemented in 1996 and emphasized early intervention and support services

(58). To enhance discrete and confidential access to psychotherapeutic assistance, programs similar to the Canadian assessment and referral service for stressed and impaired physicians

(59,

60) can further improve support systems for physicians. Finally, an open discussion of the stress encountered in medical careers is critical in the successful early recognition of impairment and suicide among physicians. Furthermore, given that many studies were conducted more than a generation ago, risk profiles and causal associations may have changed and warrant further investigation.