Pure Neuropsychiatric Presentation of Multiple Sclerosis

Case Presentation

Case 1

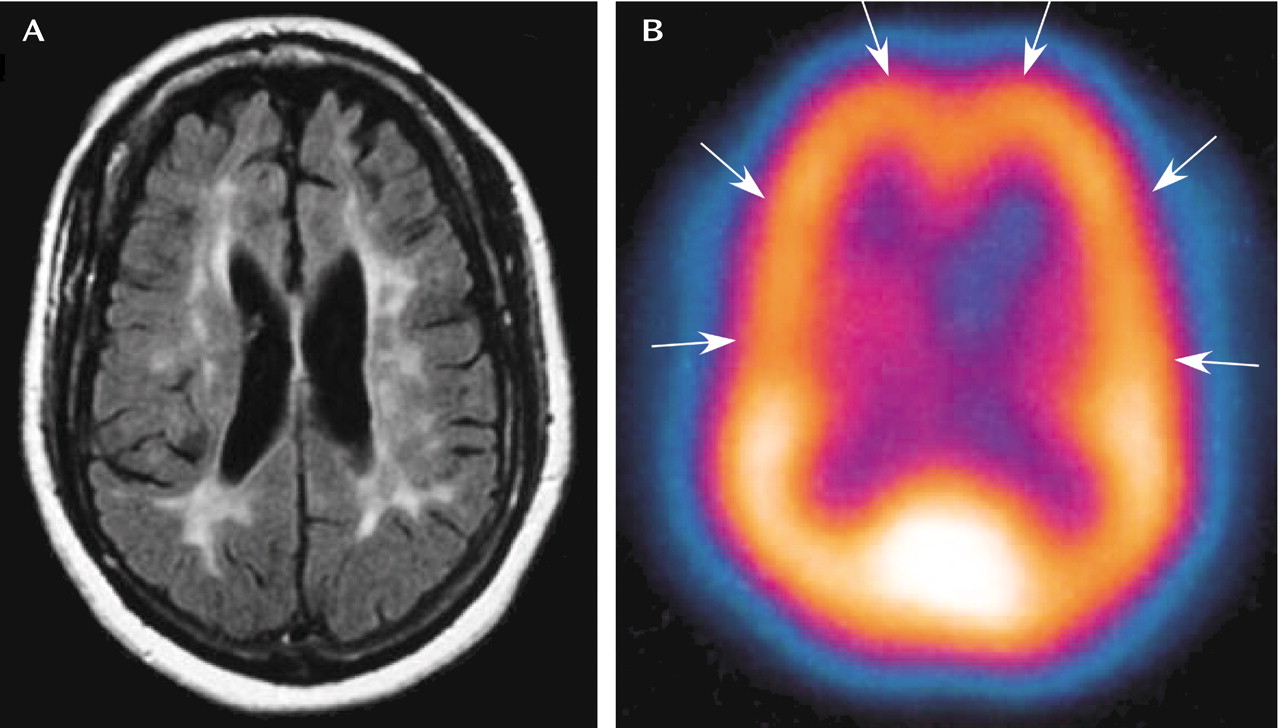

Ms. A was a 54-year-old woman who first came to an outpatient clinic because she had stopped taking her thyroxine. She was crying, appeared depressed, and reported that God had “told her” to stop taking her medications. She reported no history of psychiatric illness, substance abuse, seizures, traumatic brain injury, or exposure to poisons or toxins. Eight days later, at the psychiatry emergency care center, she was seen with pressured speech, tangentiality, disorganization, grandiose delusions (reporting receiving messages from God), labile affect, and difficulty paying attention. Collateral sources indicated that she had been hearing “God’s voice” for the last year. The voices had instructed her to leave her successful 20-year career to become an evangelist. No clinically obvious cognitive deficits were observed. Ms. A was admitted to the inpatient psychiatry unit with a preliminary diagnosis of bipolar disorder (manic episode) and was given divalproex sodium and risperidone.Initially, Ms. A appeared to respond to the mood stabilizer and antipsychotic medication. However, over the ensuing hospitalization, she had significant vacillations in affect (crying, screaming, and euphoria) and thought processes (incoherence, tangentiality, and loosening of associations) despite reported medication adherence. Of particular concern were her poor cognitive function and judgment. Although she had a high premorbid level of functioning, at the hospital, she was unable to understand medication regimens and showed little understanding of her medical condition.A concurrent medical workup was initiated to explain her symptoms. Neurology consultants performed complete physical and neurological examinations. The only abnormal finding was uniformly reduced reflexes bilaterally in the upper and lower extremities. Measures of Ms. A’s electrolyte levels and blood counts were within normal limits, as were results of a urinalysis and measures of B12, folic acid, protime and international normalized ratio, partial thromboplastine time, and liver function. The results of the following tests were negative: rapid plasma reagin, microhemagglutination-Treponema pallidum, hepatitis B and C, HIV, antinuclear antibody, rheumatoid factor, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, a urine drug screen, and a pregnancy test. Ms. A’s initial thyroid function tests revealed a slightly elevated level of thyroid stimulating hormone (6.98 μU/ml) but normal levels of free T3 and T4.A computed tomography imaging of Ms. A’s head was remarkable for reduced white matter in the parietal lobes. Subsequent magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain revealed diffuse and multifocal high signal intensity lesions in the brain parenchyma, mainly in the deep white matter of the cerebral hemispheres. These were best seen on fluid-attenuated inversion recovery images. White matter abnormalities, atrophy, and focal lesions in the remaining white matter of the cerebral hemispheres also were present (Figure 1). The lesions were suggestive of demyelinating disease, although none was enhanced with gadolinium contrast; i.e., the lesions were unlikely to be active. A single photon emission computed tomography scan identified mildly reduced perfusion to the frontal and parietal lobes bilaterally, with normal blood flow in the remainder of the brain (Figure 1).

The MRI findings suggested the possibility of multiple sclerosis, prompting a lumbar puncture. Analysis of CSF confirmed the presence of immunoglobulin oligoclonal bands. The remaining CSF indices were found to be within normal limits. Ms. A’s EEG disclosed a focus of slow-wave activity in the left temporal region, suggesting a focal abnormality. The neurological consultants diagnosed her with chronic progressive (primary-progressive) multiple sclerosis. They recommended a course of cyclophosphamide, 750 mg/m2 intravenous pulse once a month for 4–6 months, along with interferon (INF)-β1b, 0.3 mg in a subcutaneous injection every other day, for maintenance treatment of Ms. A’s multiple sclerosis. Levothyroxine, 0.075 mg/day, was reinitiated for hypothyroidism.Neuropsychological testing was administered to study Ms. A’s deficits in cognition and judgment. Results of the WAIS-III placed her in the borderline range of intellectual functioning, although her premorbid level of functioning was within the high range. She also demonstrated slowed information processing, concrete thinking, impaired memory retrieval, perseveration, and difficulties in constructional skills.Although Ms. A’s mood fluctuations decreased, she continued to have poor insight and judgment, believing that she could return to work and live independently. After administration of the Kohlman Evaluation of Living Skills (1) and a trial of living with her family with 24-hour supervision failed, Ms. A was discharged to a locked nursing home unit.

Case 2

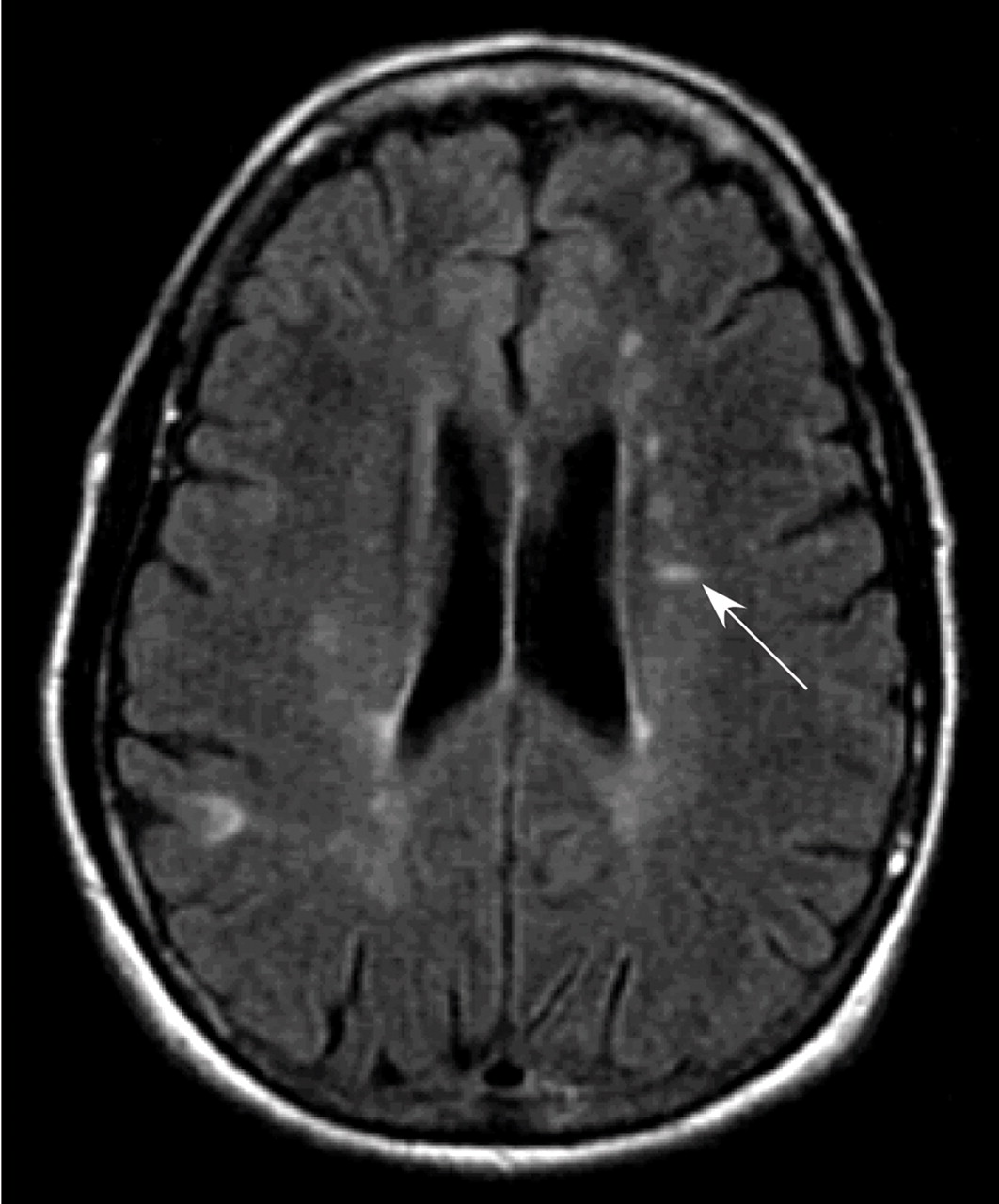

Ms. B was a 50-year-old white woman who at the time of her initial psychiatric consultation had been diagnosed with complex partial seizure disorder, which was poorly controlled because of poor medication adherence. At her evaluation, she had pressured speech, flight of ideas, and hyperreligiosity and exhibited sexually inappropriate behavior (exposing herself to staff). Ms. B expressed some grandiose beliefs and was at times guilt ridden about perceived transgressions. She was admitted to the inpatient psychiatry unit and given olanzapine, while maintaining her oral anticonvulsant regimen of 450 mg every 12 hours of lamotrigine and 600 mg in the morning and 900 mg at bedtime of oxcarbazepine. Ms. B was taking no other medications and had no history of psychiatric diagnoses, substance abuse, traumatic brain injury, or exposure to poisons or toxins.During her admission to the inpatient psychiatry unit, Ms. B refused to take her medications based largely on persecutory delusions. She was noted to have poor insight into her situation, as well as deficits in memory (an inability to provide information chronologically or accurately) and language (word approximation and neologisms). A complete physical examination did not reveal peripheral neurological deficits. Ms. B underwent a complete medical workup to better elucidate her symptoms.Her laboratory data included normal levels of electrolytes, serum protein electrophoresis, blood counts, prolactin, antinuclear antibody, and Reiter protein reagin. An EEG revealed diffuse disturbances in the brain and focal slow and sharp activity bilaterally in the frontotemporal regions as well as a frontotemporal seizure focus. An MRI examination revealed multiple high signal intensity punctate and patchy periventricular white matter lesions, including a distinctive Dawson’s finger (Figure 2). This suggested a demyelinating process, and accordingly, a lumbar puncture was performed. The CSF revealed oligoclonal bands, which supported the diagnosis of a demyelinating condition. The CSF analysis showed no other abnormalities.

Ms. B also underwent neuropsychological testing. Administration of the WAIS-III revealed a full-scale IQ of 67. This was far below expectations based on her past educational (a master’s degree) and vocational background. Ms. B exhibited word-finding and retrieval difficulties, despite her intact conversational speech. Her recall of auditory verbal or contextual information was severely impaired and characterized by confabulation. She was unable to grasp the concept of alternating sequences on the Trail Making test (2). Perseveration and significant distractibility were also noted. Ms. B’s MMPI results showed an elevation of scores on the hypomania scale. Her score on the Kohlman Evaluation of Living Skills showed deficits in the awareness of dangerous household situations, an inability to identify appropriate actions for sickness and accidents, and an inability to budget monthly income or to use banking forms.During her stay, Ms. B refused to take multiple antipsychotic medications, including olanzapine, ziprasidone, and risperidone. However, she did continue to take her seizure medications. After refusal of multiple medication interventions, the neurology consultants simply requested that Ms. B be followed as an outpatient. She was discharged with the recommendation of 24-hour supervision and was deemed unfit to return to work.

Discussion

Footnote

References

Information & Authors

Information

Published In

History

Authors

Metrics & Citations

Metrics

Citations

Export Citations

If you have the appropriate software installed, you can download article citation data to the citation manager of your choice. Simply select your manager software from the list below and click Download.

For more information or tips please see 'Downloading to a citation manager' in the Help menu.

View Options

View options

PDF/EPUB

View PDF/EPUBGet Access

Login options

Already a subscriber? Access your subscription through your login credentials or your institution for full access to this article.

Personal login Institutional Login Open Athens loginNot a subscriber?

PsychiatryOnline subscription options offer access to the DSM-5-TR® library, books, journals, CME, and patient resources. This all-in-one virtual library provides psychiatrists and mental health professionals with key resources for diagnosis, treatment, research, and professional development.

Need more help? PsychiatryOnline Customer Service may be reached by emailing [email protected] or by calling 800-368-5777 (in the U.S.) or 703-907-7322 (outside the U.S.).