Cocaine dependence represents a chronically relapsing disorder. Intense drug wanting or craving precipitated by drug use reminders or cues is widely recognized as a major precipitant of relapsing drug abuse

(6). In vivo functional neuroimaging techniques such as positron emission tomography (PET) and functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) have identified a functional anatomy of cue-induced drug craving. Cocaine craving provoked by prototypical drug use scenarios or mental imagery of personal drug use results in significant increases in neural activity in circumscribed brain areas in abstinent cocaine-dependent individuals. Such areas of cocaine craving-related activation include prominent limbic and paralimbic brain regions such as the amygdala, anterior cingulate, orbitofrontal cortex, insular cortex, and the nucleus accumbens

(7–

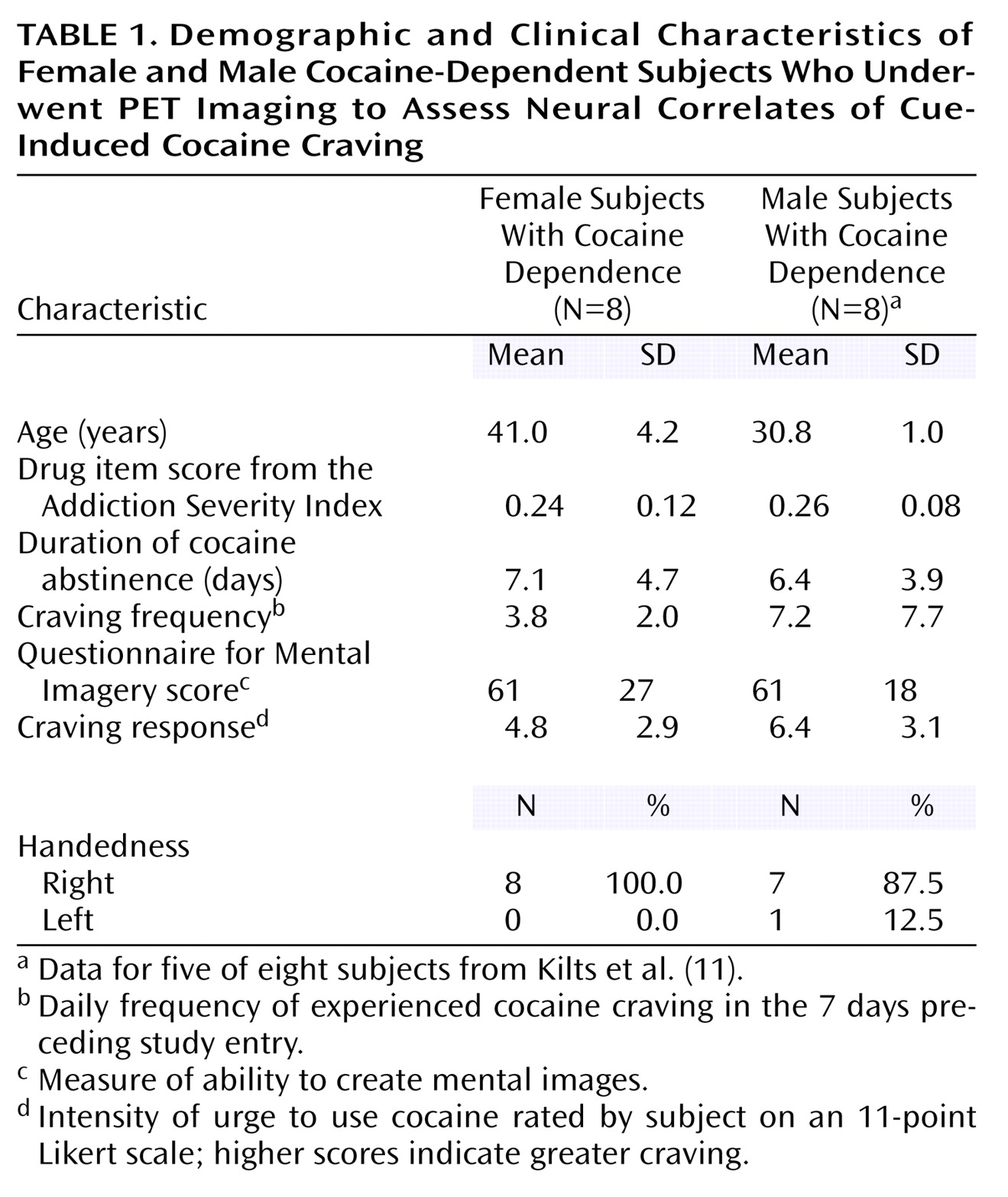

13). The majority of these imaging studies have focused only on men as subjects, while fewer have examined a mixed-sex sample; none have investigated cocaine craving in an exclusive sample of cocaine-dependent women. Several functional brain imaging studies unrelated to drug craving have, however, compared female and male cocaine-dependent groups and reported significant sex differences. Male, but not female, cocaine-dependent subjects exhibited frontal cortical perfusion abnormalities

(14). Relative to men, cocaine-dependent women exhibited less evidence of neuronal damage in frontal cortical gray and white matter by in vivo magnetic resonance spectroscopy

(15). Together, these studies suggest that women may have less frontal abnormalities associated with cocaine dependence than do men.

Discussion

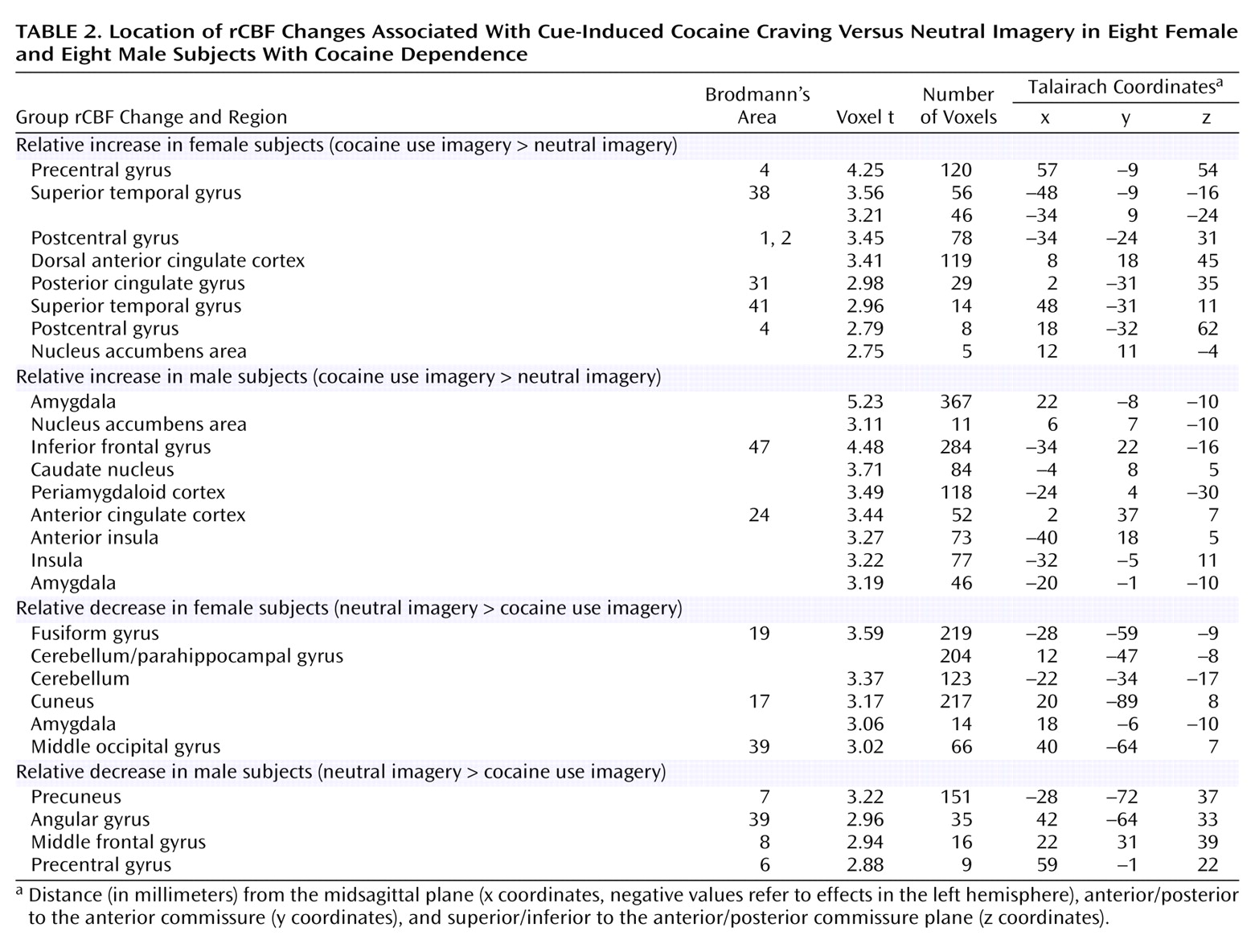

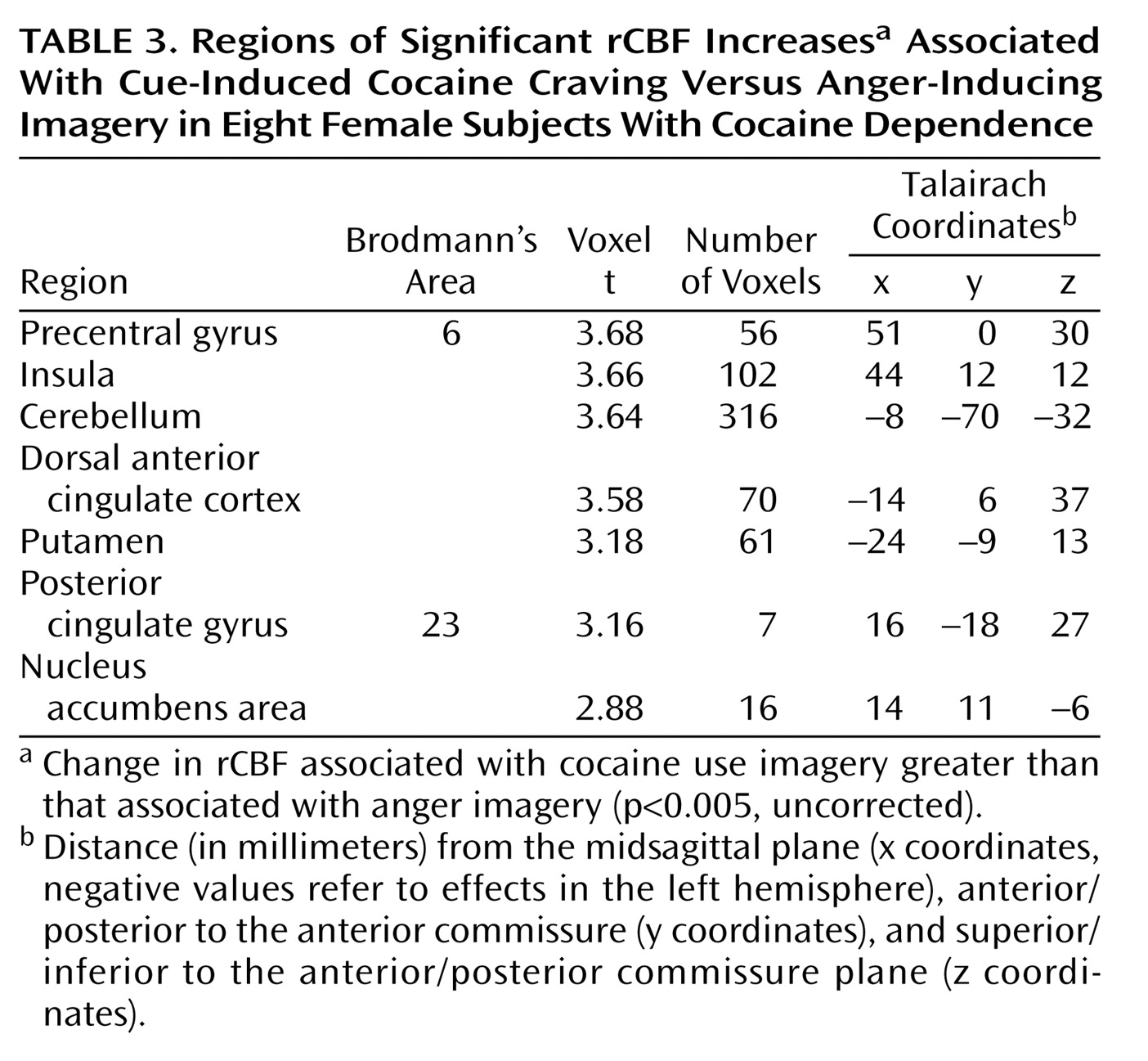

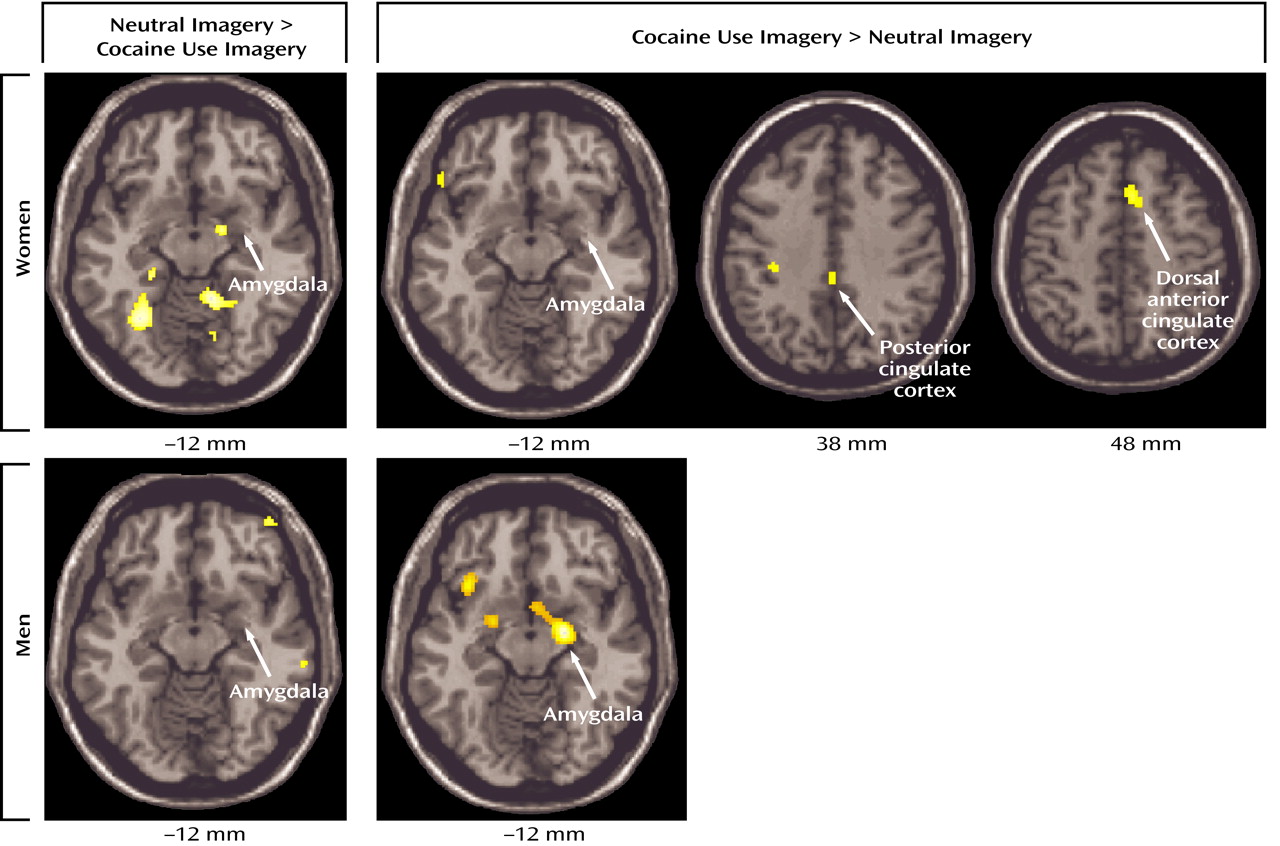

The results of this PET neuroactivation analysis suggest that cue-induced cocaine craving in cocaine-dependent women is associated with distributed activations in the central sulcus, temporal cortex, dorsal anterior and posterior cingulate cortex, and a right ventral striatal area that includes the nucleus accumbens. These cocaine craving-related activations survived correction for activations related to the use of guided mental imagery for craving induction (drug-neutral imagery condition) as well as activations related to the arousing, affective, and mnemonic corollaries of induced drug craving (anger imagery condition). Possible functional attributes of these cocaine cue-related activations include mental imagery of motor and somatosensory representations of cocaine use associated with precentral and postcentral gyrus activations. The posterior cingulate activation may relate to the retrieval of vivid autobiographical memories

(20). Additionally, a parametric [

15O]H

2O PET study of reward value for chocolate implicated the posterior cingulate cortex in the processing of incentive salience, perhaps further encoding the desire to forego a stimulus even though it is deemed pleasurable

(21). The cocaine cue-induced activation of the posterior cingulate cortex may thus relate to processes involved in establishing the momentary difference between wanting to use cocaine and the mental representation of liking cocaine. The additional relationship of posterior cingulate activation to mood state changes

(22) does not explain its association with cocaine use imagery, since emotions of anger, sadness, and happiness were negligibly affected by cocaine use imagery. The observation that posterior cingulate cortex activation persisted when the cocaine use cue condition was contrasted with the anger cue condition (

Table 3) suggests further that it is related to incentive processing rather than to autobiographical memory recall or emotion processing. The rostral superior temporal gyrus is a paralimbic association cortex area involved in multimodal object processing and the analysis of speech-like sounds

(23). Its role in cue-induced cocaine craving in cocaine-dependent women is not obvious but may relate to monitoring emotional experiences

(24) to the drug use cue.

The nucleus accumbens, a component of the ventral striatum, has been convincingly implicated in the processing of anticipated and attained rewards

(25–

27), perhaps particularly when reward probability is unpredictable

(28). The cocaine cue-induced activation of the right nucleus accumbens area in this study seems plausibly related to the heightened expectation of cocaine reward when conditioned drug craving increases cocaine-seeking behaviors. It is of interest that cocaine craving related to cocaine use imagery was also associated with activation of the right nucleus accumbens in a separate PET study of identical design in cocaine-dependent men

(11), and a matched male sample (

Table 2,

Figure 2). Cocaine-induced cocaine craving was also associated with nucleus accumbens activation

(29). However, ventral striatal activation to drug cues has not been noted in prior PET and fMRI studies in cocaine-dependent subjects

(7–

9,

12,

13). This difference in study findings may relate to differences in the nature of the drug cue used to provoke craving or the craving response. Similar to the results of a previous fMRI study of incentive cues in a monetary incentive delay task

(30), the cocaine cue used in this study was associated with activation of a dorsal anterior cingulate cortex site. This site contributes to the valuation of incentive cues

(31), and may, with the ventral striatum, guide reward-based decision making

(32). These findings support the involvement of a neural circuit comprising the nucleus accumbens and dorsal anterior and posterior cingulate cortex in the evaluation of cocaine use cues as behavioral incentives, the process of defining their anticipated reward value biased by the motivation state to attain a cocaine reward, and the selection of choice behaviors.

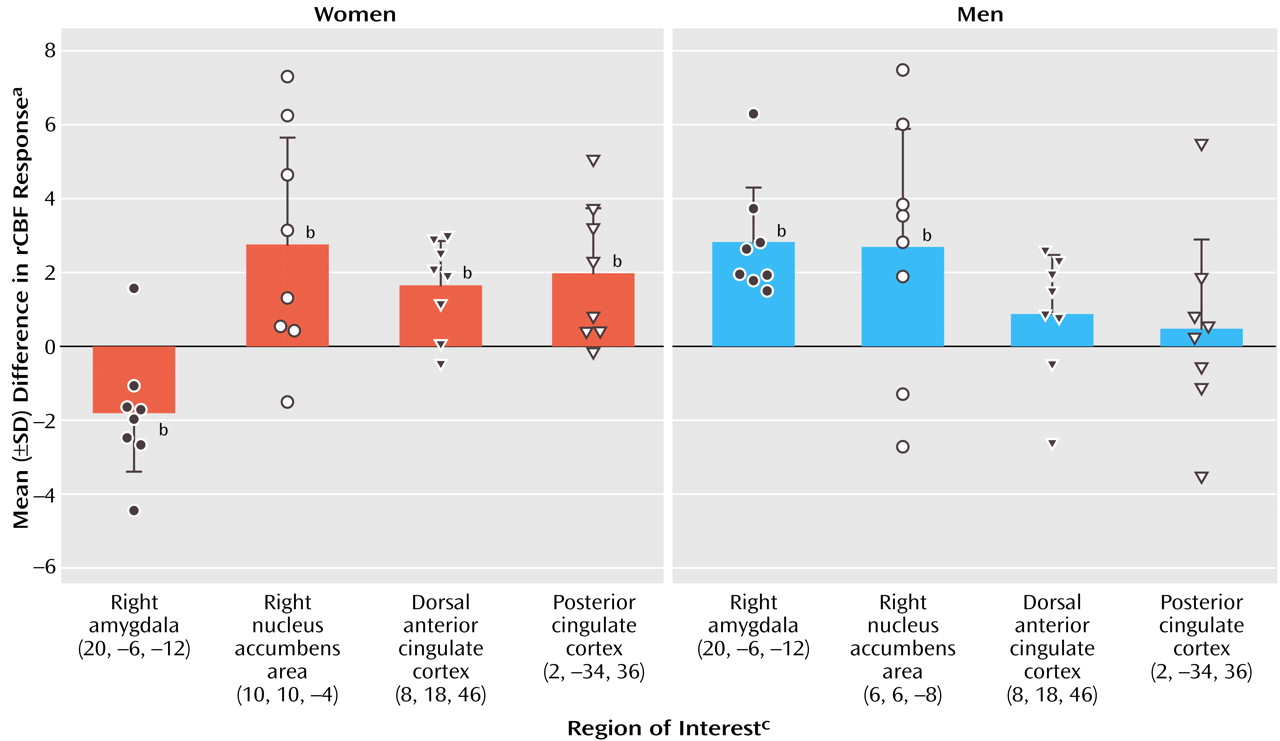

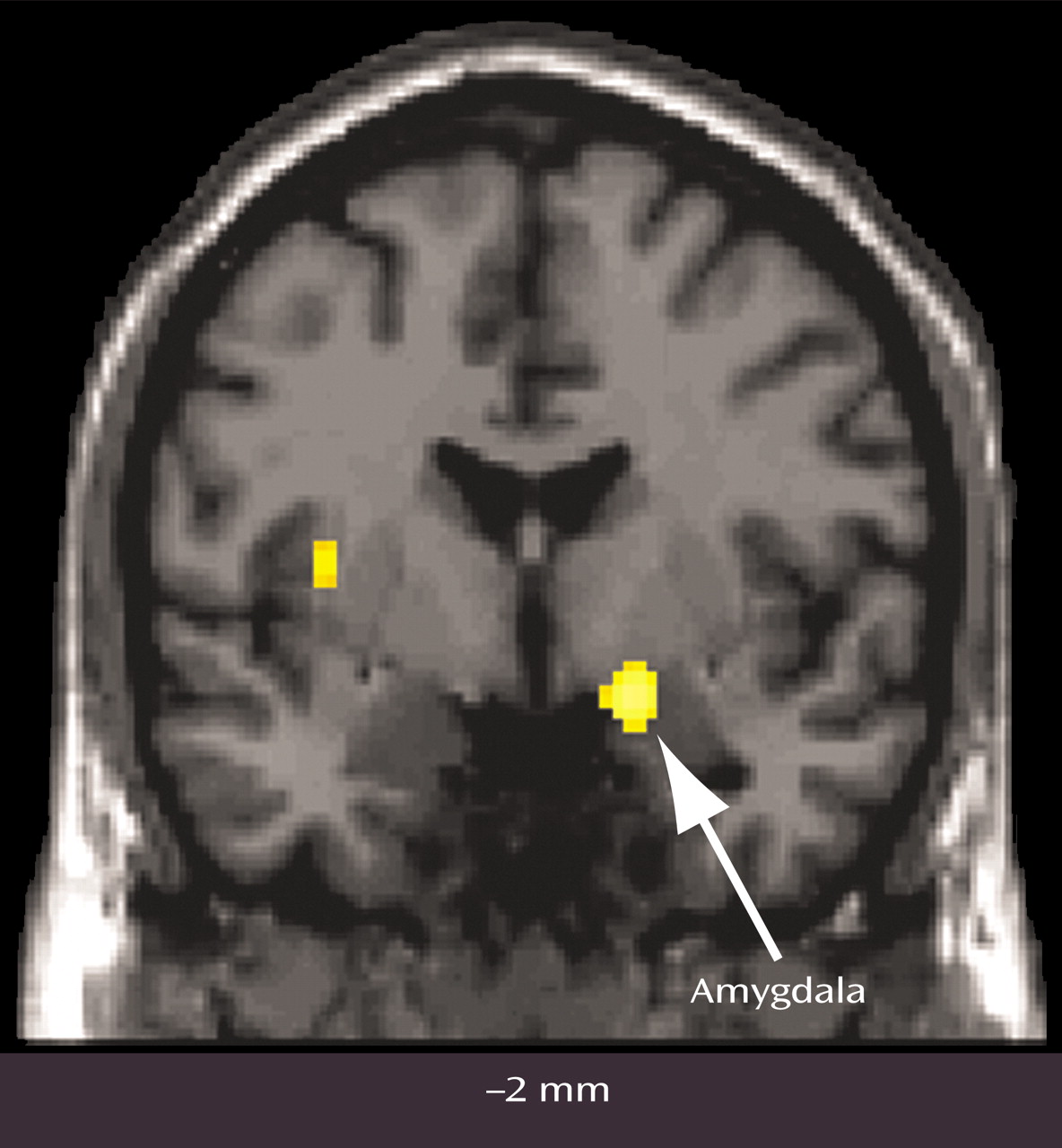

Cocaine craving provoked by cocaine use imagery was also associated with decreases, relative to the neutral imagery condition, in visual processing areas, the cerebellum, and right amygdala. A recent study of opiate craving induced by script-guided imagery of autobiographical drug use in opiate-dependent subjects similarly noted a relative decrease in rCBF in the striate and extrastriate cortex

(33). The finding of a cocaine cue-induced decrease in amygdala activity in cocaine-dependent women is particularly noteworthy, since a cue-induced activation of the amygdala is commonly observed in male and predominantly male samples of cocaine-dependent subjects

(7,

8,

11). The differential effect of sex on amygdala response associated with cue-induced cocaine craving was confirmed in a direct voxel-wise comparison (

Figure 3). The interpretation for this sex difference—that drug use imagery represents a strongly conditioned cocaine cue in men but not women—seems unlikely with the comparable craving response in both sexes. An alternative interpretation for the observed sex difference in amygdala response is that the women studied formed distinct conditioned associations with drug use compared with men, leading to distinct conditioned neural responses to cocaine cues. A recently completed PET study of rape-related posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in women indicated that rape trauma imagery was similarly associated with a significant decrease in right amygdala activity (unpublished 2003 study of CD Kilts et al.). Perhaps the decreased amygdala activity associated here with cocaine use imagery in cocaine-dependent women reflects the association of trauma with past cocaine use. While none of the female subjects fulfilled DSM-IV criteria for PTSD, four of eight subjects reported past major traumas (e.g., rape, childhood physical and sexual abuse) in the PTSD subsection of the SCID. While the presence of a trauma history clearly does not establish the specific association of trauma with past cocaine use, it does perhaps increase the probability of such a learned association. While a preferential relationship between stressors (e.g., prostitution, heading a single-parent household, abusive relationships) and cocaine abuse for women needs to be systematically investigated, it has been proposed that the neurobiology of other psychiatric diagnoses such as major depression is strongly influenced by past trauma experiences

(34).

We assessed whether the conditioned decreased amygdala response to cocaine cues in cocaine-dependent women is attributable to feedback from a brain area possibly involved in cognitive control of drug-seeking behavior. The dorsal anterior cingulate cortex or cognitive subdivision of the anterior cingulate cortex has been proposed to subserve executive functions related to error detection

(35), monitoring competition between responses

(36), and inhibiting goal-inappropriate behavior

(37), in addition to decision-making

(32) and motor planning

(38) related to reward processing. The dorsal anterior cingulate cortex also has been implicated in animal models in the modulation of cocaine cue-induced relapse of drug taking

(39). A role of the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex in the response to drug cues in cocaine-dependent women may thus relate to computing conditional probabilities of the relationship of the drug cue to drug availability, and if low then to dampen the response of areas involved in cue analysis. Some evidence for a negative correlation between the amygdala and dorsal anterior cingulate cortex response to cocaine use imagery was observed (r=–0.68, df=6, p<0.07), suggesting that the latter response reflects an executive control of the cue valuation functions of the amygdala. The use of [

15O]H

2O PET studies precluded the assessment of the relative time course of the amygdala and dorsal anterior cingulate cortex responses, a relationship perhaps revealing of a regulatory role of the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex.

A secondary objective of this study was to compare in cocaine-dependent women and men the location of neural activations related to cue-induced cocaine craving. The assembled comparison sample of matched cocaine-dependent men indicated cocaine craving-related activations in a network of limbic, paralimbic, and striatal areas. Common craving-related activations for the female and male subjects were observed and included the right nucleus accumbens area, dorsal anterior cingulate cortex, and left superior temporal gyrus. These common activations suggest that both sexes process cocaine use memories as incentive cues guiding reward-based decision making

(32). Observed sex differences suggest, however, that the neural correlates of cue-induced cocaine craving associated with cocaine dependence differ between men and women. As discussed, cocaine-dependent men, but not women, exhibited bilateral amygdala activation in response to the mental reenactment of cocaine use. Men, but not women, also exhibited craving-related paralimbic activations in the insula, ventral anterior cingulate, and orbital frontal cortex. The lack of paralimbic activations associated with conditioned craving responses in cocaine-dependent women may be reflective of the lack of amygdala activation to cocaine cues, since the amygdala has extensive reciprocal connections with the paralimbic cortex

(40). The comparative lack of amygdala and paralimbic brain activations to a cocaine cue in women may underlie observed sex differences in craving reactivity to drug cues

(16), or sex differences in its emotional

(41) or other corollary states, in cocaine-dependent individuals. Anterior cingulate activation by cocaine cues of a more ventral and anterior region representing its affective subdivision

(42,

43) has been consistently reported for male cocaine-dependent subjects

(8,

9,

11,

13). This response may however precede the onset of cocaine craving

(12) and may rather relate to the regulation of emotional responses

(44) to cocaine cues. The direct voxel-wise comparison of female and male subjects provided some evidence for sex differences in the frontal cortical response to cocaine cues, with women having greater responses. This difference may relate to evidence from in vivo single photon emission computed tomography

(14) and magnetic resonance spectroscopy

(15) studies suggesting lesser frontal cortical abnormalities in cocaine-dependent women.

In addition to a neutral imagery condition, cocaine use imagery was compared with an anger imagery condition to correct for activations related to the arousing, attention-grabbing, and episodic memory properties of cocaine use imagery

(11). Retained activations, relative to comparisons to the neutral imagery condition, related to cue-induced cocaine craving included the dorsal anterior and posterior cingulate cortex, nucleus accumbens, and precentral gyrus. These results support the selective role of these brain regions in cue-induced cocaine craving, specifically related to the processing of cocaine cues as incentive stimuli for reward-directed decision making.

Limitations of this study include a relatively small sample size and the inclusion of two female subjects that were not currently in drug treatment programs. Conclusions related to possible sex differences in the neural correlates of cue-induced drug craving associated with cocaine dependence should be considered as highly preliminary. Group differences other than sex (e.g., social development, early and current trauma) undoubtedly contributed to observed differences in neural activations related to cocaine craving. The same craving induction and PET image acquisition paradigm was used for the female and male subjects. However, apparent sex differences also have to be interpreted in light of the fact that the reproducibility of craving-related activations in a same-sex population using the same craving induction protocol has not been determined.

Women represent a significant proportion of cocaine abusers in the United States yet have been essentially ignored as the subject of functional brain imaging studies of the addiction process. If this applied technology represents an important step in defining the neurobiological bases of addiction

(45), then this step must be taken with study designs that include female cocaine abusers. The results of this study highlight craving-related and distributed activations along the central sulcus, temporal pole, cingulate cortex, and nucleus accumbens in cocaine-dependent women. Commonalities and potential differences between the sexes in the brain’s response to cocaine use reminders may be important in defining the need for, and guiding the development of, sex-specific treatment strategies for minimizing relapse in cocaine-dependent individuals.