Neuropsychological deficit is one of the most common manifestations of brain involvement in HIV infection and has been demonstrated in numerous studies. Deficits in memory and learning, mental flexibility, psychomotor slowing, reaction time, and decision-making speed are commonly reported in HIV infection

(1). The risk of cognitive decline in HIV infection has stimulated the attempt to identify risk factors for this decline. To date, age

(2,

3) and education

(4) have been identified as being associated with a greater risk of cognitive deficit, whereas depression

(5) and mild head injury

(6) do not appear to account for cognitive deficit in the context of HIV infection. Several studies

(7) have reported that drug abuse is associated with greater cognitive decline. Most of the studies have focused on intravenous drug users, with relatively little evaluation of the impact of alcohol use or abuse on cognitive function.

The high prevalence of alcohol abuse in gay populations and the detrimental effects of alcohol on the immune system make alcohol use a risk factor that necessitates further study in HIV infection. One study

(8), using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID), reported a high lifetime prevalence of alcohol abuse or dependence in both HIV-positive and HIV-negative gay men (41% and 30%, respectively). The immunological effects of chronic alcoholism provide further reason to consider alcohol use in the context of HIV-related neuropsychological deficit. Alcohol is associated with greater HIV viral replication in cell culture

(9), fewer tumor necrosis factor receptors on stimulated macrophages

(10), a depletion of lymphocytes

(11), and changes in host mechanisms and specific immune response

(12).

Studies of cognitive effects of alcohol in HIV infections have involved intravenous drug users or have used limited cognitive assessments. Fein et al.

(13) excluded intravenous drug users and found an additive effect of HIV infection and active, chronic alcohol abuse on auditory P3A evoked potentials, which are markers of early stages of information processing and correlate with performance on neuropsychological tasks. Further, Fein et al.

(14) compared HIV-negative subjects with chronic alcoholism in long-term abstinence with a group of HIV-positive subjects currently abusing alcohol and found that both groups had delayed P3A latency. These studies, which excluded intravenous drug users, suggest that chronic alcohol use in HIV-infected individuals affects cognitive function; however, these studies used limited measures of cognitive performance.

To our knowledge, no previous study has examined the effect of past alcohol abuse in HIV-infected individuals who were not currently abusing alcohol or other drugs. A study of detoxified alcoholics who were HIV negative found that cognition was within normal limits after an average of 6 years of excessive alcohol consumption

(15). It is unclear, however, whether similar effects would be demonstrated in subjects with HIV infection. van Gorp et al.

(16) found that a history of alcohol abuse may have an effect on cognitive function in the context of a second disorder that affects brain function, namely, bipolar disorder. Subjects with bipolar disorder who also had a history of alcohol dependence demonstrated greater impairment in frontal lobe function than those with no history of alcohol dependence. These data illustrate that chronic alcohol abuse can complicate and compound other illnesses that affect the brain and suggest a need for an examination of the role of past alcohol abuse on HIV neuropsychological dysfunction.

Although previous studies clearly support the importance of examining the potential interaction of alcohol use and HIV infection on cognitive function, they have been confounded by inclusion of intravenous drug users or limited cognitive assessments. Furthermore, it is important to exclude the potential impact of current abuse in the assessment of the potential residual effects of alcohol abuse. Therefore, to evaluate the potential interaction of HIV infection and previous alcohol abuse, we studied subjects who reported stable levels of moderate alcohol use.

Method

Subjects

The subjects of this study were drawn from a larger sample of HIV-positive and HIV-negative gay and bisexual men who were participants in a longitudinal study of neurobehavioral abnormalities in HIV infection. The subjects were divided into two groups on the basis of a positive or negative history of past alcohol abuse and then compared in their performances in a battery of psychological tests. Participation in the study included an extensive neuropsychological examination, structured diagnostic interview (SCID), and psychiatric rating scales. Subjects were recruited into the project from a variety of sources, including an AIDS Clinical Trials Unit, advertisements in newspapers and other publications directed toward the gay community, several local gay community organizations, and word of mouth. No subjects were recruited specifically because of the suspicion or presence of neurobehavioral symptoms. All subjects were aware of their HIV status at the time of their participation in the project. The 1993 CDC AIDS case definition was used to classify HIV status. Subjects with histories of intravenous drug use, learning disability, head injury (unconsciousness for more than 1 hour), or other neurologic diseases and subjects who met diagnostic criteria for alcohol abuse or dependence within the past 6 months were excluded from the study. We excluded subjects with episodes of unconsciousness greater than 1 hour to avoid potential confounding effects of more serious brain injuries. None of the subjects used in this study had a history of unconsciousness for longer than 1 minute.

The HIV-positive and HIV-negative subjects with and without a history of alcohol abuse did not differ in the prevalence of past history of marijuana abuse or dependence or in current use of marijuana. Use of cocaine or other drugs was uncommon in these subjects, and no subject met criteria for abuse of or dependence on other drugs. Subjects included in this study were HIV-positive asymptomatic individuals and HIV-negative individuals with a self-reported, stable pattern of alcohol use of less than 210 g of ethyl alcohol per week over a 1-year time period. The criterion of less than 210 g of ethyl alcohol per week translates into a drink a day or less, ensuring that heavy drinkers were excluded from the study while not being so strict as to limit the numbers of subjects able to be included in the study. This standard of alcohol use should ensure that current alcohol effects do not confound the data. After complete description of the study to the subjects, written informed consent was obtained.

Neuropsychological Test Battery

The measures used in this study were selected on the basis of several considerations, including previous demonstration of the measure’s sensitivity to the neuropsychological effects of HIV-1 infection, coverage of a broad range of psychological abilities, and the measure’s theoretical relationship with the purported subcortical nature of deficits. The test battery included the WAIS-R

(17), Wisconsin Card Sorting Test

(18), Verbal Fluency Test

(19), Verbal Concept Attainment Test

(20), Trail Making Test Parts A and B

(21), visual span forward and backward from the Wechsler Memory Scale—Revised

(22), Grooved Pegboard Test

(23), Paced Auditory Serial Addition Test

(24), and Selective Reminding Test

(25). Depression and anxiety were measured using the Hamilton Rating Scale for Anxiety and the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression

(26). The test battery included a number of reaction time measures that have been found to be sensitive in previous studies of early-stage HIV infection

(27,

28). Simple reaction time was examined for both dominant and nondominant hands. Choice Reaction Time and Go/No Go tests were also performed. Response times for all tasks were recorded in milliseconds. The test battery required approximately 3.5 hours to administer. Research assistants performed all assessments in one day. A more complete description of the test battery can be found in a previous report on this longitudinal sample

(29).

In addition to examining the mean performance on each of these measures, we examined the proportion of subjects rated as impaired across all measures. There has been considerable variability among previous studies in the criteria used for defining impairment on individual measures and across measures. Most studies of asymptomatic HIV-positive patients indicate that the deficits tend to be subtle. We decided to define impairment on each test as a score that was one or more standard deviations below the mean of an HIV-negative gay male control group reported previously

(5). These criterion scores were used to derive a summary impairment rating, which represented the number of measures that fell in the impaired range. For the Paced Auditory Serial Addition Test, Selective Reminding Tests, and Reaction Time tests, it was decided to collapse scores across the numerous measures within each test (because of interrelationships of the scores) and regard performance on a test as impaired if any one of the measures from that test fell beyond the criterion. This prevents abnormalities on any of these tests from disproportionately influencing the summary impairment rating. The test battery yielded a total of 15 scores that were used in computation of the summary impairment rating. Overall performance was rated as impaired if six or more of the 15 measures fell in the impaired range. We consider this criterion for impairment (six [40%] of 15) to be a conservative measure that identifies subjects with subtle but consistent neuropsychological abnormalities.

Drug and Alcohol Use Measures

Drug use and alcohol use were examined with both syndromal and quantitative approaches. Trained raters using the SCID interviewed all subjects. Specific diagnostic ratings were reviewed and confirmed by a senior clinician with extensive experience in use of structured ratings of psychopathology. The diagnosis of primary interest for this investigation was lifetime alcohol abuse or dependence.

In addition to taking the syndromal approach to identifying alcohol use, we attempted to quantify the extent of alcohol use in these subjects. A quantitative rating that provides a reliable estimate of alcohol consumption (I. Grant, personal communication) was used for this study. The variable of interest derived from this rating was the mean weekly alcohol consumption over the past year. The simultaneous use of syndromal and quantitative estimates of alcohol use is advantageous in the investigation of the role that past alcohol abuse or dependence may have in the neuropsychological abnormalities observed in some patients with HIV infection.

The data were analyzed by grouping subjects according to the presence of specific alcohol use patterns and alcohol-related diagnoses. This group of subjects was chosen from the larger pool of subjects on the basis of maintaining a stable alcohol use pattern over the past year and an average weekly ethyl alcohol consumption of less than 210 g. The subjects were subdivided into groups on the basis of a classification of their HIV status: positive-asymptomatic and negative. The relationship between past alcohol abuse or dependence and neuropsychological performance was examined by using analysis of variance (ANOVA). Before we examined the neuropsychological data, we assessed the potential confounding effects of age, education, depression, and anxiety. The data were analyzed by using a two-by-two (disease status by alcohol abuse history) ANOVA. To reduce the possibility of type I error, analyses were restricted to the 15 core neuropsychological measures identified in our previous studies of individuals with HIV infection.

Results

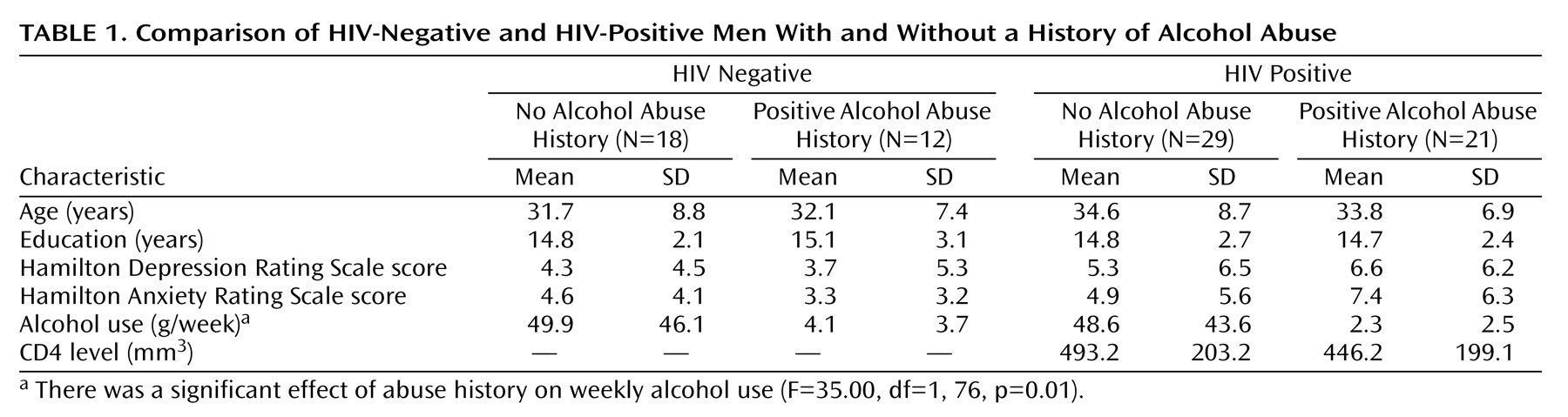

On the basis of diagnostic interviews, 12 of the HIV-negative men and 21 of the HIV-positive men had met criteria for alcohol abuse or dependence at some time in their life; 18 of the HIV-negative and 29 of the HIV-positive men had not met criteria for either alcohol abuse or dependence. The means for the analyses are presented in

Table 1. There were no significant effects of HIV status or alcohol abuse history and no interactions of age, education, depression, or anxiety. Similarly, there was no difference in the proportion of subjects with a history of drug abuse other than alcohol (data not shown). In addition, the CD4 levels in the HIV-positive subjects were analyzed with a t test and were not significantly different (

Table 1). Therefore, the impairment measures were analyzed without further consideration of the effects of these variables.

Table 1 also illustrates a significant difference in the amount of alcohol consumed per week: subjects with no history of alcohol abuse or dependence, regardless of HIV status, consumed more alcohol per week than the subjects with a history of alcohol abuse or dependence. This demonstrates that any difference in cognitive performance in the current examination cannot be attributed to current use of alcohol.

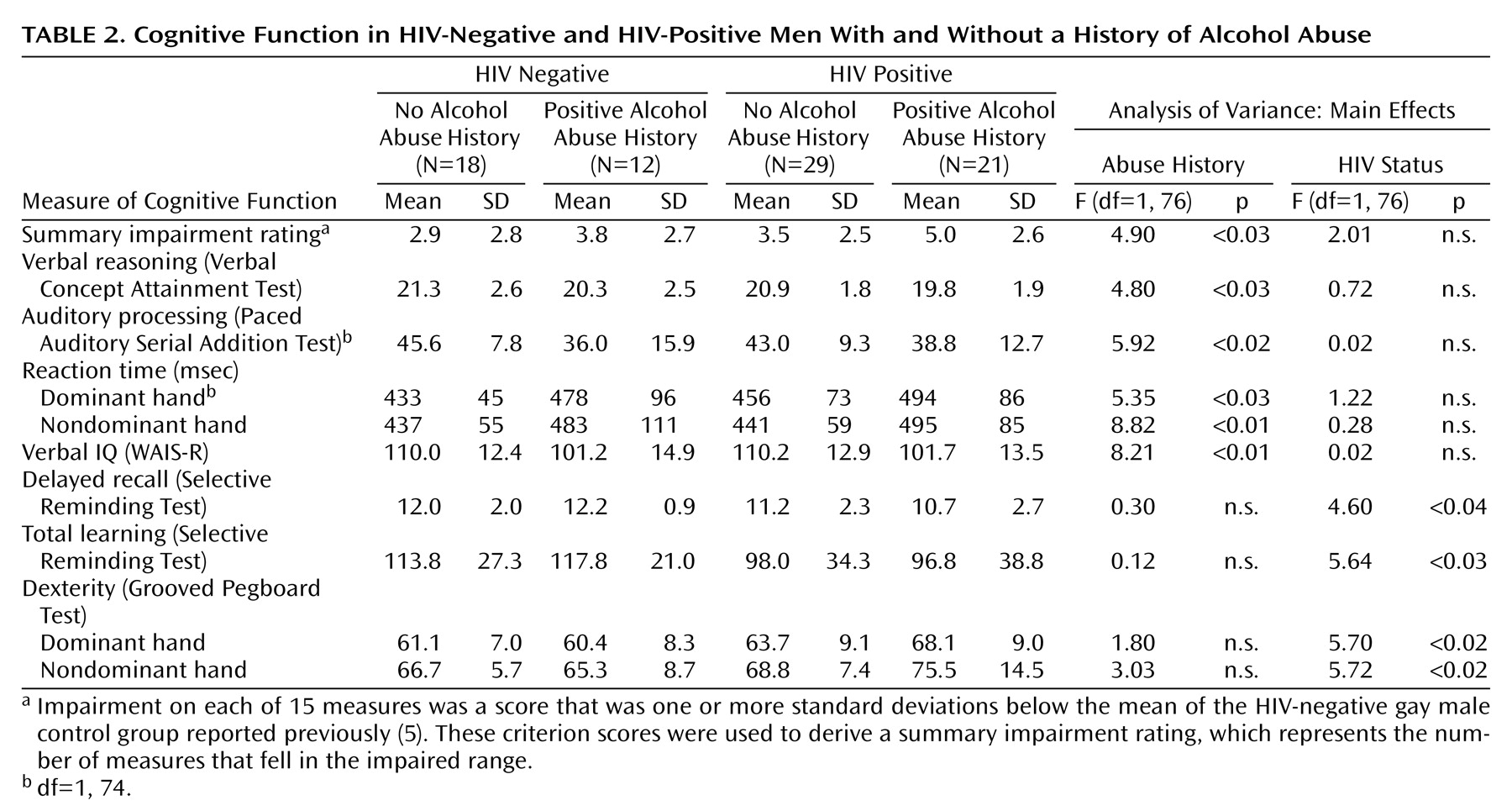

The neuropsychological data were analyzed by using a two-by-two (disease status by alcohol abuse history) ANOVA. The groups were compared on the summary neuropsychological impairment rating, which represents the number of tests with results falling into the impaired range.

Table 2 reveals that there was a significant main effect for history of alcohol abuse on the summary impairment rating. Subjects with a past history of alcohol abuse were more impaired than those with no past history. There was no independent effect of HIV status and no interaction. Further analysis of the individual neuropsychological measures showed significant effects for alcohol use history on measures of verbal reasoning, auditory information processing, reaction time, and verbal IQ. Significant effects for HIV status were observed on measures of memory (delayed recall), total learning, and dexterity. Significant interaction effects were also observed, which led to analysis of simple main effects.

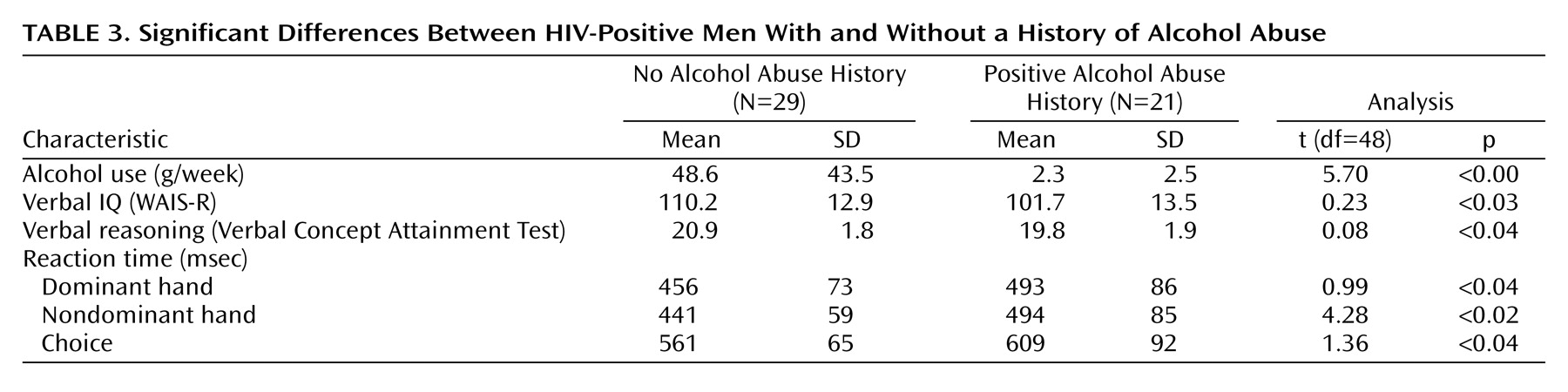

The alcohol abuse histories within the HIV-negative and HIV-positive groups were analyzed separately with t tests. There were no differences in functioning between the HIV-negative groups with and without a history of alcohol abuse. There were significant differences in verbal IQ, verbal reasoning, and reaction time between the HIV-positive subjects with and without a history of alcohol abuse (

Table 3). This suggests that the effect of a history of alcohol abuse on cognitive functioning is influenced by the coexistence of a second disease state, in this case HIV infection.

Discussion

These data indicate that HIV infection and a previous history of alcohol abuse have independent effects on cognitive function. As previous studies have found, subjects with asymptomatic HIV infection performed worse than HIV-negative subjects on measures of memory and dexterity. Previous studies by Fein et al.

(13,

14) have demonstrated an independent effect of alcohol abuse and HIV infection on electrophysiologic and cognitive measures in HIV-infected subjects with chronic alcohol abuse. The findings of the current study are consistent with those of Fein et al. in identifying independent effects of alcohol use and HIV infection, but no interaction. However, the most intriguing aspect of the current results is that the subjects in the current study were not currently abusing alcohol. Subjects were selected on the basis of modest alcohol consumption (less than 210 g/week) over the past year.

In view of the provocative nature of these findings it is essential that the effects of potential confounding variables be examined. We determined that the relationship between a history of alcohol abuse and neuropsychological performance could not be attributed to extraneous variables such as age, education, depression, anxiety, or history of other drug abuse. In addition, among the HIV-infected subgroups, there was no difference in CD4 levels between those with and without a history of alcohol abuse. This indicates that the observed differences cannot be attributed to greater immune decline. Furthermore, we demonstrated that these effects could not be attributed to current levels of reported alcohol use. In fact, subjects with a previous history of alcohol use reported using significantly less alcohol than subjects with no previous history.

This study is consistent with and extends previous studies of the impact of alcohol abuse on neuropsychological function in subjects with HIV infection. Previous studies have shown that ongoing, chronic alcohol abuse causes a decrease in functioning in an HIV-positive population

(13,

14). Similar to those studies, the current study found that alcohol use and HIV infection had independent effects with no interaction. The data presented here further indicate that a history of alcohol abuse, even with minimal current use, may also have an impact on cognitive function. Subjects were selected on the basis of modest current alcohol consumption, and mean levels of consumption were very low in all subgroups. In fact, the subjects in both HIV-positive and HIV-negative groups with a previous history of alcohol abuse used significantly less alcohol than those without a history of alcohol abuse (

Table 1). This suggests that subjects with a previous history of alcohol abuse have made significant lifestyle changes. Nevertheless, in spite of lower levels of current consumption, subjects with a history of alcohol abuse performed more poorly than those without this history.

These findings suggest that previous alcohol abuse may create a nidus of vulnerability that may be exacerbated by the effects of HIV infection on the brain. In the absence of HIV infection, chronic alcohol abuse does not appear to lead to substantial cognitive impairment. Eckardt et al.

(15) found no effects on cognition in otherwise healthy and recently detoxified alcoholics. The subjects in that study were young men, comparable in age to the current subjects. The current findings are consistent with the observations of Eckardt et al. in that there were no differences in cognitive function between the HIV-negative subgroups with and without a history of alcohol abuse. This suggests that a history of alcohol abuse per se in this age group does not lead to persistent cognitive deficit. However, the current findings suggest that the residual effects of previous alcohol abuse may be expressed in the presence of a second disease state that affects the brain.

In contrast to the HIV-negative subgroups, HIV infection and a history of alcohol abuse was associated with worse neuropsychological performance. This concurs with the results of van Gorp et al.

(16), who found that detoxified subjects with bipolar disorder had impaired frontal lobe functioning that was not found in bipolar subjects without a history of alcohol abuse. In the context of the current study, these data suggest that alcohol abuse may lead to a subthreshold alteration of brain function. Although this alteration in brain function may be insufficient to lead to overt cognitive dysfunction, there may be a vulnerability to the impact of a second, independent process (e.g., HIV infection).

It is also possible, as suggested by a reviewer of a previous version of this article, that ongoing alcohol abuse in the presence of HIV infection may increase the risk of nonreversible neuropathological change, which may persist even after the individual reduces his or her alcohol intake. The men with a previous history of alcohol abuse or dependence in this study appear to have made a decision to reduce their alcohol intake, as reflected in the fact that they reported current alcohol use that was significantly less than subjects without a history of abuse or dependence. Unfortunately, the database in the current study did not collect information on when subjects decreased their alcohol consumption. Rather than a more passive or permissive process, these data could suggest a more dynamic process in which the timing of cessation of alcohol consumption may be an important predictor of subsequent neuropsychological morbidity.

There are some methodological issues that require consideration in the interpretation on these results. The estimates of current alcohol use were based on self-report, which may lead to an inconsistency between actual alcohol use and reported alcohol use. Particularly of concern is the observation that subjects with a history of alcohol abuse reported significantly lower levels of current consumption and, in fact, were virtually abstinent. However, the diagnosis of a lifetime history of alcohol abuse was also based on self-report. It seems unlikely that subjects would systematically underreport current use but also report past abuse. Rather, it seems more likely that the lower level of current alcohol use in the subjects with a past history reflects lifestyle changes that have been made by those subjects.

These data raise important implications about the potential adverse effects of alcohol abuse. The primary neurological and systemic effects of chronic alcohol abuse are well-known. In addition, this and other studies suggest a lack of significant cognitive effects in detoxified alcohol abusers. However, there is evidence to suggest that alcohol abuse may create a greater vulnerability to the effects of other disease processes that affect the brain. Individuals at risk for alcohol abuse and other disorders that could affect the brain might be cautioned about the potential combined risk. In this context it is noteworthy that previous epidemiological studies of HIV-infected subjects as well as those at risk for HIV infection have demonstrated higher rates of histories of alcohol abuse

(7). Thus, interventions directed toward reduced alcohol consumption in subjects at risk for HIV infection may become an important approach in prevention of factors that contribute to cognitive dysfunction in the setting of HIV infection. In relation to clinical management of HIV-infected individuals, it may be important for health care providers to be aware that a past history of alcohol abuse, regardless of current use, may be associated with a greater risk of cognitive impairment.