Despite evidence that the prevalence of psychotic symptoms and paranoid ideation in older community-dwelling adults is not uncommon—i.e., rates of up to 10% have been reported, depending on sample characteristics and selection criteria

(1–

6)—data in the United States have been limited to three studies in the past 20 years, all of which focused exclusively on paranoid ideation

(4–

6). Two were general community studies conducted in rural and urban areas in North Carolina

(4,

5), and the third involved a sample of African Americans recruited from senior centers in New Orleans

(6). This paucity of data is unfortunate since psychotic and paranoid symptoms in older persons without cognitive impairment have been linked to the development of dementia, higher mortality, impaired functional ability, depression, visual and hearing impairments, and poor physical health

(1–

6).

In the United States, among all age groups, racial differences in paranoid symptoms have been noted, with blacks having a significantly greater prevalence than whites

(7). This finding takes on added clinical importance because older blacks are among the most rapidly expanding population subgroups. Moreover, the older black population, particularly in urban areas, has become more diverse as a result of immigration from the Caribbean, i.e., the number of Caribbeans nationwide is estimated to be over two million

(8). Hence, factors that influence symptom prevalence among urban blacks may be different from factors reported in other geographic areas. Indeed, Blazer and colleagues

(5) speculated that paranoid symptoms in older blacks might represent an appropriate response to a hostile environment rather than a psychopathic trait. However, their study did not separately examine older blacks, which might have clarified whether different elements played a role in the etiology of their symptoms. In the study of elderly African Americans in New Orleans

(6), the sample was derived from senior centers, so it is unclear how representative the findings were of older blacks in general. Moreover, the authors did not indicate whether African Caribbeans were included in their sample. Thus, there are compelling reasons to examine psychotic and paranoid symptoms in other geographic regions of the United States that include a culturally diverse group of older black adults.

In order to examine the factors that predict psychoses and paranoid ideation in aging persons, we employed a modified version of George’s social antecedent model of psychiatric disorders in older adults

(9). She postulated six stages of risk factors, with later stages hypothesized to be increasingly proximate precursors of psychiatric disorders. The first three stages consist of demographic factors (e.g., race, gender, and ethnicity), early events and achievements (e.g., education and early traumatic events), and later events and achievements (e.g., financial status, later traumatic events). The fourth and fifth stages consist of social integration and support and various vulnerability factors (e.g., chronic stressors such as physical illness, alcoholism, and mental distress). The sixth stage consists of provoking agents (e.g., acute life events) and coping strategies (e.g., beliefs and behaviors). Thus, the model has the potential to test the concurrent effects of social and clinical variables.

Method

Sample

With the Wessex Census Summary Tape File 3 for Kings County (Brooklyn, N.Y.), we extracted black and white persons 55 years of age and over. To conserve costs, block groups that had fewer than 10% blacks or 10% whites were eliminated from the black and white files, respectively. We randomly selected, without replacement, block groups as the primary sampling unit.

Based on 1990 census totals, the estimation of approximate populations by race and gender was performed with sampling weights. The sampling weights were computed as the reciprocal of the selection probabilities for each observation. Our study design called for interviewing a minimum of 200 persons in each of four ethnic groups: Caucasians, African Americans, African Caribbeans from English-speaking islands, and African Caribbeans from French-speaking islands. Data collection took place from 1996 to 1999.

An effort was made to interview all persons in a selected block group by knocking on doors. To enhance response rates, subjects from the selected block group were also recruited at senior centers and churches and through personal references; 30% of the sample was recruited through these means. The overall response rate was 77% of those contacted. Persons with significant cognitive impairment—i.e., scores of 4 or less on the Mental Status Questionnaire

(10)—were excluded from the overall study. The final community sample consisted of 878 blacks and 219 Caucasians. However, for the present analyses, we excluded persons with possible dementia, according to the criteria of Zarit et al.

(11), i.e., those with scores <8 on the Mental Status Questionnaire. Therefore, the current study included 1,027 persons, 206 Caucasians and 821 blacks, of whom 282 were African Americans, 288 were African Caribbeans from English-speaking islands, 248 were African Caribbeans from French-speaking islands, and three could not be classified. The weighted totals were 429,089 persons, of whom 118,668 were black and 310,421 were Caucasians; the weighted totals by gender were 172,787 men and 256,302 women.

After providing a complete description of the study to the subjects, we obtained written informed consent. The institutional review board of the State University of New York Downstate Medical Center approved the study.

Instruments and Variables

The literature had indicated that psychotic and paranoid symptoms in later life may be associated with physical illness, cognitive deficits, impaired vision and hearing, difficulties in daily functioning, depression, environmental stressors, diminished social support, increased age, gender (male), race (black), and immigrant status

(1–

6). These findings also suggested that coping strategies and beliefs or attitudinal systems might mediate the effects of some of these factors, although none of the earlier studies had specifically examined these variables. We used a modified version of George’s theoretical model

(10) as the scaffolding in which to incorporate the relevant variables previously noted in the literature, along with several additional coping and attitudinal variables that we postulated as being important.

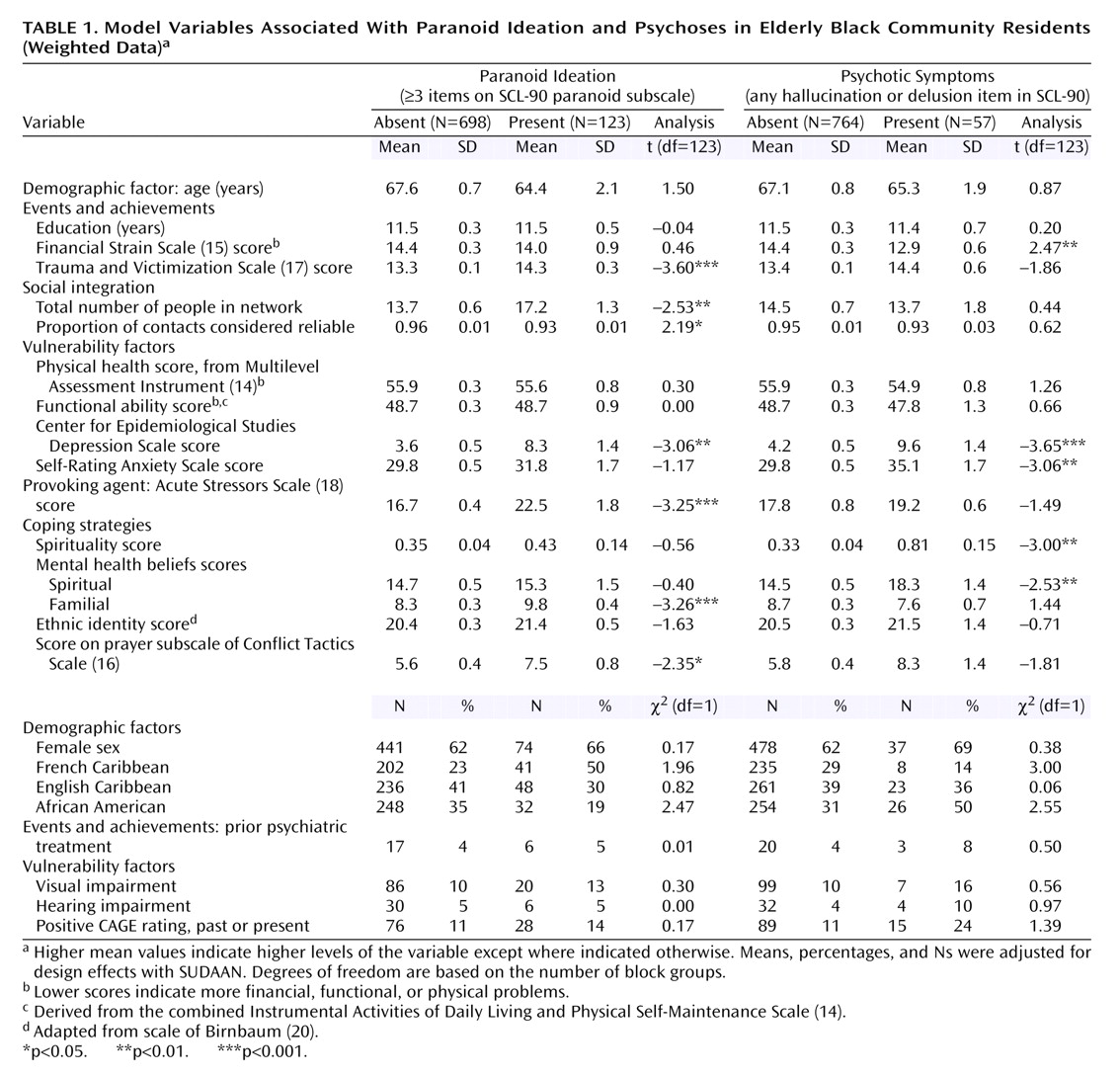

We operationalized 21 dependent and three independent variables (

Table 1) that were derived with the following instruments and methods:

1.

The Self-Rating Anxiety Scale

(12)2.

The Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D Scale)

(13)3.

A physical illness score that represented the sum of seven health care items and 13 illness categories derived from the Multilevel Assessment Inventory Physical Health Status (lower scores indicate worse health)

(14)4.

A functional impairment rating derived from combining the Instrumental Activities of Daily Living and Physical Self-Maintenance Scale

(14) (lower scores indicate more impairment)

5.

The Financial Strain Scale

(15), for which lower scores denote more strain

6.

The Conflict Tactics Scale

(16), which was modified for this study and then subdivided into seven subscales (prayer, calm discussion, keeping feelings inside, hitting, shoving, hurting, or using a weapon) by using principal components analysis with varimax rotation

The Trauma and Victimization Scale

(17), which examined 18 lifetime traumatic events (e.g., physical abuse, sexual assault, physical assault, and witnessing violence)

7.

The Acute Stressors Scale

(18), which examined 11 life events that may have occurred in the past month

8.

The Network Analysis Profile

(19), which generated variables concerning network size, intimacy, reliability of contacts, advice giving, and material support

9.

The Ethnic Identity Scale, a seven-item scale adapted from Birnbaum’s scale

(20) that examines affinity for one’s ethnic group and perceived prejudice

10.

The CAGE Questionnaire

(21), for which a positive item response in the past or present was used as an indicator for possible alcohol problems

11.

The Mental Health Beliefs Scale, a 93-item scale developed using community focus groups, which was divided into six belief subscales about the causes and cure of mental illness (spiritual, religious, stress, family heredity and rearing effects, environmental, empathy or understanding) by using principal components analysis with varimax rotation

With respect to the latter, we used all six items from the paranoid subscale, the four most severe items from the 10-item psychoticism subscale dealing with auditory hallucinations and delusions (e.g., others can control or read one’s thoughts; thoughts are not one’s own), and two supplementary items about visual and olfactory hallucinations. “Spirituality” was assessed by assigning a score of 1 if the respondent saw a spiritualist, purchased items from a religious shop, or believed in casting spells; respondents received a score of 2 if they endorsed at least two of these items. Using items from CES-D Scale, the Self-Rating Anxiety Scale, and supplemental items about suicidality, we determined the level of major depression, based on DSM-IV symptom criteria. We also included items regarding the use of and perceived need for psychiatric services.

The internal consistencies (Cronbach’s alphas) for the scales were the following: Self-Rating Anxiety Scale, 0.95; CES-D Scale, 0.85; functional impairment, 0.72; Financial Strain Scale, 0.88; Conflict Tactics Scale, 0.84; Trauma and Victimization Scale, 0.68; Acute Stressors Scale, 0.77; Mental Health Beliefs Scale, 0.87; Ethnic Identity Scale, 0.68; and the SCL-90 paranoid ideation subscale, 0.70. Alphas above 0.60 are considered acceptable

(23).

Three dependent variables were created:

1.

Paranoid ideation was considered present if the respondent endorsed three or more items on the paranoid subscale of the SCL-90. We used a conservative cutoff point that was approximately two standard deviations above the mean scale score for psychiatric outpatients in the original report on the SCL-90 by Derogatis and coworkers

(22).

2.

Psychotic symptoms were considered present if the respondent endorsed any of the six items dealing with hallucinations or psychotic delusions on the SCL-90 or among the supplementary items.

3.

Psychotic symptoms or paranoid ideation was considered present if the respondent scored positive on either the paranoid ideation or psychotic symptoms variables described.

For Haitian respondents, the questionnaire was translated into Creole and then back-translated according to the methods described by Flaherty and colleagues

(24). Interviewers were trained with audiotapes and videotapes, and they were generally matched to respondents from similar ethnic backgrounds. Interrater reliability with intraclass correlations ranged from 0.86 to 1.00 for the scales in this sample. The interviewers were periodically monitored with audiotapes.

Data Analysis

In order to control for intrablock clustering effects and for “without replacement” sampling, data analysis was performed by using SUDAAN 7.5.4

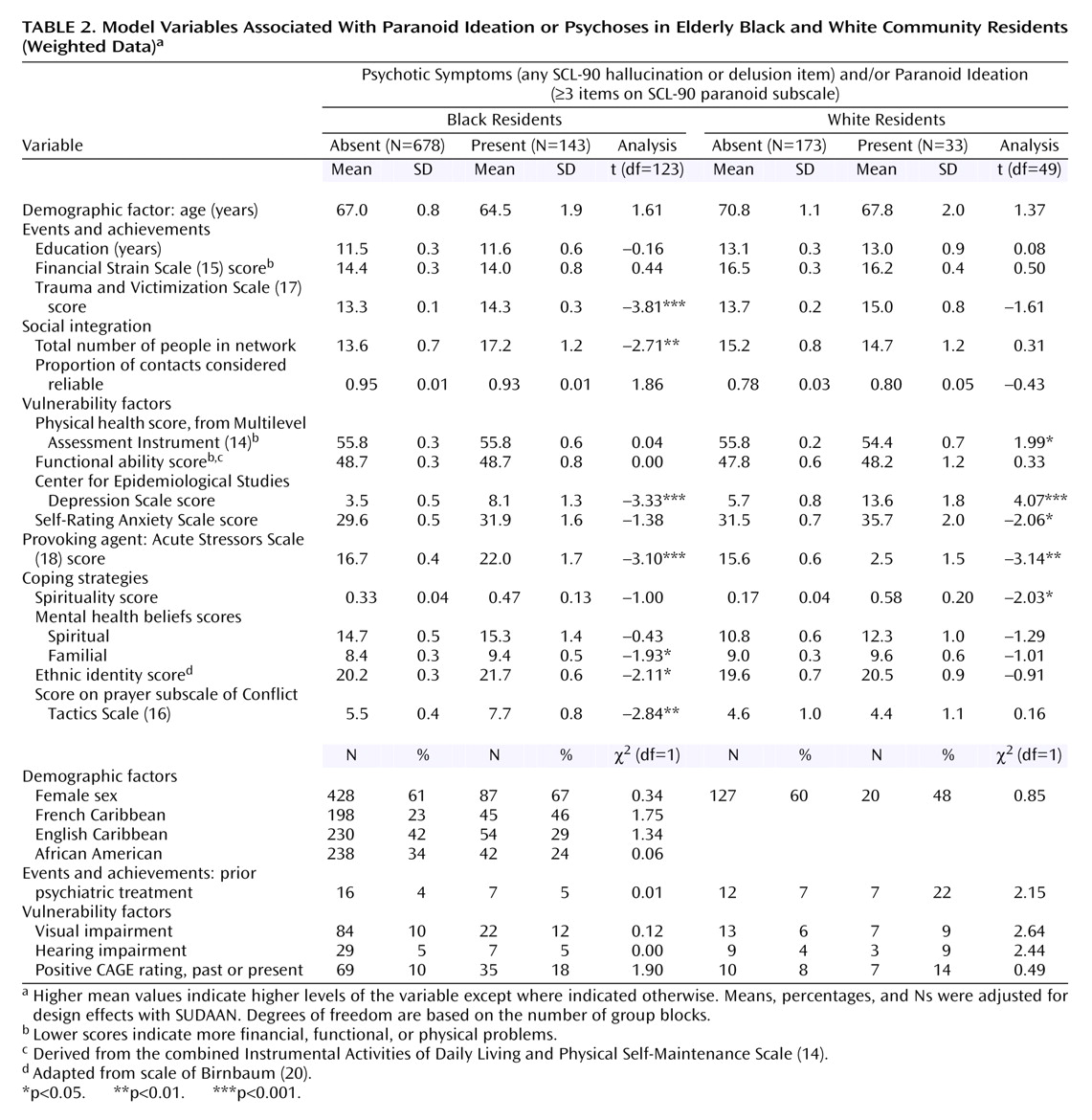

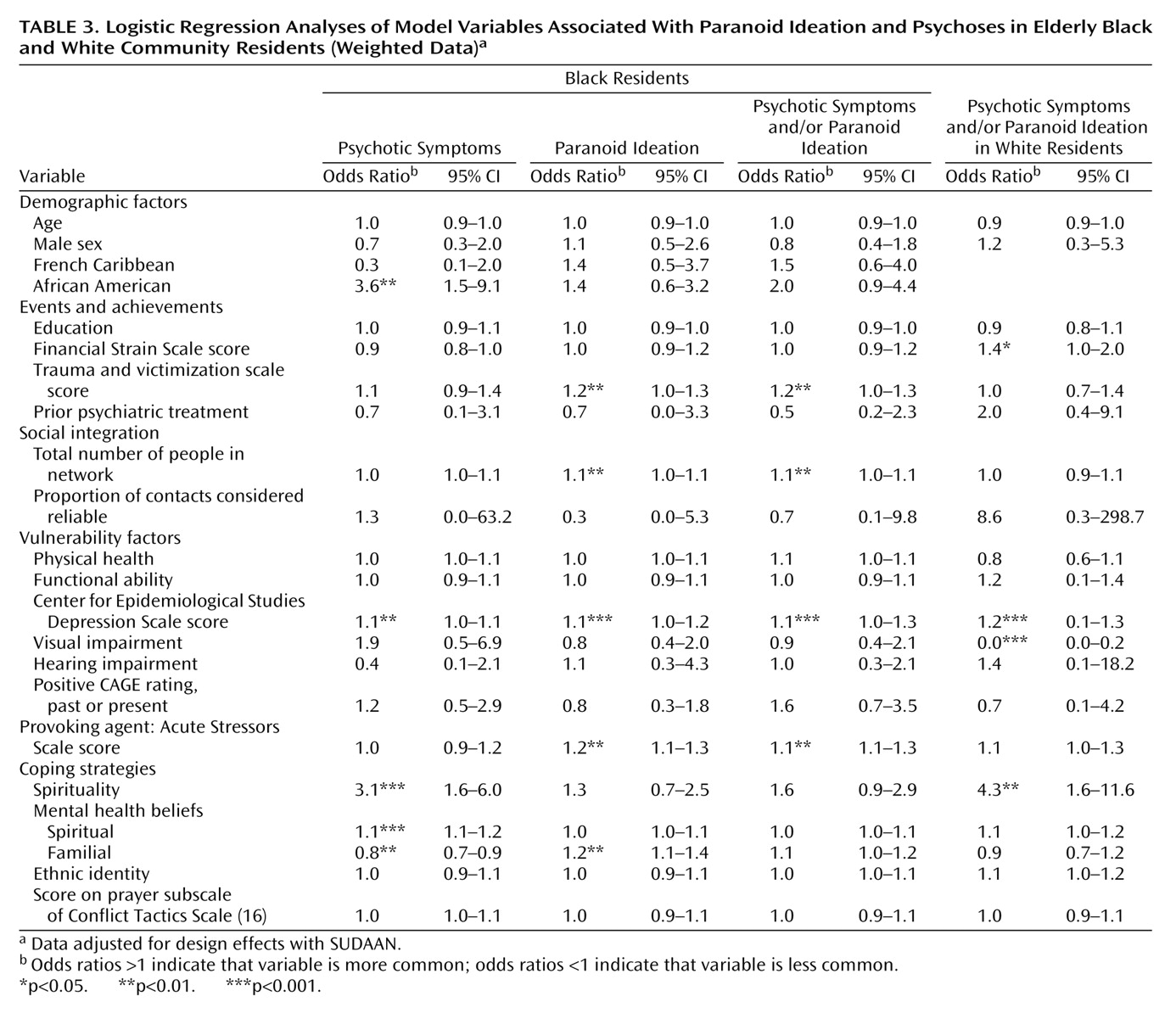

(25). The unit of analysis was the individual. All analyses were conducted by using sampling weights. Initially, we conducted bivariate analyses to examine the relationship between independent and dependent variables; t tests and chi-square analyses were used for continuous and categorical independent variables, respectively. With respect to the selection of independent variables, for instruments that generated potentially more than one variable, we conducted preliminary t tests and selected one or more variables from the measure that had substantial association (p<0.10) with any of the dependent variables (preliminary analyses not shown). For the final analyses, we included demographic variables such as gender, age, race, and education, as well as ethnicity for the analyses of the black groups, i.e., African American, French African Caribbean, English African Caribbean (note that only the first two ethnic groups were included as dummy variables in logistic regression analyses). Next, each of the dependent variables was examined separately by race by using logistic regression. Because of concerns regarding problems of multicollinearity, we did not enter anxiety symptoms into the logistic regression analyses because of its strong correlation with depressive symptoms (r=0.76). We selected depressive symptoms rather than anxiety symptoms because the variable yielded a more powerful model. Finally, because of the low number of whites reporting psychoses alone (N=9), we did not examine this variable when we looked separately at the white sample, but we examined it in combination with paranoid ideation.

Discussion

Our study of a cognitively intact multiracial sample of older adults in Brooklyn, N.Y., revealed levels of symptoms, especially among the black groups, that were substantially higher than have been reported elsewhere

(1–

6), although the levels were comparable to the levels of psychotic symptoms reported among a younger and predominantly Hispanic sample of primary care patients (mean age=53 years) in Northern Manhattan

(26). Overall, in our study, roughly one in seven persons ages 55 and older experienced paranoid ideation or psychotic symptoms. However, nearly one-fourth of the older blacks expressed paranoid ideation or psychotic symptoms, which was significantly greater than for the whites. Among the older whites, roughly one-tenth reported such symptoms, which was consistent with the prevalence rates in the literature. Even after appropriate design effects were taken into account, the inclusion of a Caribbean-born population that reflected the demographics of Brooklyn primarily accounted for the higher levels of symptoms than had been reported previously in older black samples. Indeed, the prevalence of paranoid ideation among older blacks born in the United States was only slightly higher than among older whites (13% versus 9%), whereas the levels among French Caribbeans were four times that of white persons.

What are the implications of these findings? First, the absence of a significant association between measures of functional impairment and paranoid ideation or psychotic symptoms suggests that these symptoms were not substantially affecting daily living. On the other hand, we found evidence that paranoid ideation or psychotic symptoms were associated with emotional dysfunction. For example, both older whites and blacks with paranoid ideation or psychoses had significantly more depressive symptoms and a greater prevalence of major depression than persons without such symptoms, i.e., 13% of the persons with paranoid ideation or psychoses had major depression versus 1.5% of the persons without depression. Also, among blacks, our analysis indicated that persons with psychotic symptoms and/or paranoid ideation had significantly more anxiety symptoms.

The strong relationship between depression and paranoid ideation and psychoses raises questions as to whether the latter are manifestations of depressive illness. Slightly over one-third of persons with psychotic symptoms and/or paranoid ideation met CES-D Scale criterion for clinical depression. Blazer and colleagues’ study of older adults in North Carolina

(5) found that depressive symptoms were significant predictors of paranoid symptoms at a 3-year follow-up. Unfortunately, these authors did not examine to what extent paranoid ideation predicted subsequent depression. It is plausible that causality is bidirectional, with paranoid ideation and psychoses inducing depressive symptoms and vice versa. Longitudinal data are needed to tease apart these relationships.

Only 14% of the sample with psychotic symptoms and/or paranoid ideation had ever received psychiatric treatment, and even among those with both depression and psychotic symptoms and/or paranoid ideation, only 24% had received treatment. This suggests that more services are required. However, this conclusion must be tempered by the fact that only 11% of these persons thought that they required mental health services. Furthermore, there were racial disparities in the desire for treatment among persons with psychotic symptoms and/or paranoid ideation, with twice as many whites as blacks believing that they required services. This lack of interest in mental health services may reflect the acceptability of some level of these symptoms, especially given the weak association with functional impairments. This appears to be particularly likely among older African Caribbeans, whose use of and perceived need for mental health services were substantially lower than that of whites and African Americans.

For example, among older Caribbean immigrants, especially French Caribbeans from Haiti, the lingering effects of colonialism and the various types of political oppression, coupled with magical thinking and widespread belief in witchcraft and voodoo, may allow for greater cultural acceptance of paranoid ideation and modest levels of psychoses

(27,

28). Moreover, whereas older blacks born in the United States have become increasingly more willing to use mental health services

(7), older Caribbeans have been found to have negative views of mental health workers, and they still prefer to use their families, churches, or self-healing to deal with mental distress

(27).

George’s model

(9) was significant for both racial groups, and it helped uncover a variety of factors that heretofore had not been implicated in the etiology of psychoses and paranoid ideation in older persons. Most notably, particularly among blacks, acute stressors, lifetime traumatic events, beliefs about causes of mental illness, and belief in or use of spiritualists were found to be associated with paranoid ideation or psychotic symptoms. The fact that acute stressors and lifetime traumatic events were significant for blacks but not whites suggests that among older blacks, paranoid ideation and psychotic symptoms may be either manifestations of distress or ways of coping with adverse events. The associations with spiritual beliefs and practices raise questions as to whether psychotic symptoms reflect belief systems rather than abnormal psychiatric symptoms. Conversely, persons with such symptoms may be more apt to turn to spiritualism. Because our cross-sectional data cannot answer this question, an exploration of health beliefs and behaviors concerning spiritualism should be included in future studies.

Four variables—depressive symptoms, financial strain, visual impairment, and social contacts—that had been implicated in earlier studies

(1–

6) were significant in this study. However, whereas depressive symptoms were associated with paranoid ideation and psychoses in both racial groups, visual impairment and financial strain were only significant among whites, and network size was significant only for blacks. Moreover, the direction of the latter was contrary to expectations in that persons with paranoid ideation and psychoses had larger social networks. The larger networks among those with symptoms further reinforce our contention that these symptoms in the absence of functional impairment are socially acceptable in the black community. They also indicate that individuals with these symptoms remain sociable and are able to engage others. Racial differences in financial strain may reflect the fact that the black elderly population has uniformly low income so that there was little gradient in financial strain. It is not clear as to why there were racial differences in the effects of visual impairment; however, this variable has not been consistently implicated in other studies

(3–

5), and in our study, the variable is based on self-reports of impairment rather than on clinical assessments.

Our data further underscored the heterogeneity of the older black community. In multivariate analyses, African Americans showed a significantly higher proportion of psychotic symptoms, but they showed significantly lower levels of psychotic symptoms and/or paranoid ideation versus the Caribbean-born blacks, which primarily reflects the high levels of psychotic symptoms and/or paranoid ideation among French African Caribbeans. Thus, even after accounting for various clinical, social, and belief factors within the black community, intragroup symptom differences remained that could not be explained by our model but presumably reflected psychosocial elements that were not elicited in this study. Such underlying elements are further suggested by the fact that there were substantial intragroup differences with respect to perceived need for psychiatric treatment among those with psychotic symptoms and/or paranoid ideation. The model was also not completely successful in accounting for black-white differences in psychotic symptoms, paranoid ideation, and psychotic symptoms and/or paranoid ideation, which were attenuated but did not disappear once all the social, attitudinal, and clinical variables were examined concurrently.

The high prevalence of paranoid ideation and psychoses among this urban population of older adults, especially among blacks, points to a potential public health issue. While these symptoms are not associated with appreciable functional impairment, they are significantly associated with increased depression (in both blacks and whites) and anxiety (in blacks). Moreover, paranoid ideation and psychoses have been reported previously to be associated with higher mortality, poor physical health, and cognitive decline. Appropriate caution should be used in interpreting our findings since this study was confined to one urban setting and used cross-sectional data. Further exploration of these issues in other urban settings with longitudinal analyses can help clarify the impact of paranoid ideation and psychoses on the well-being of elders living in the community.