For most of the 20th century, depressed patients were dichotomized by using the categories “single episode” versus “recurrent” and “unipolar” versus “bipolar.” There is now ample evidence that almost all depressions are recurrent to a greater or lesser degree

(1–

5). Now the question arises whether almost all recurrent depressions are bipolar to a greater or lesser degree.

The distinction between bipolar and unipolar disorder served our field well in the early days of psychopharmacology. However, this distinction has been challenged in the last decades by the following:

Despite converging evidence on its clinical validity, what has been termed “bipolar II disorder,” with its requirement of discrete episodes of hypomania, has proven to be a diagnosis on which it is difficult to achieve good agreement between clinicians

(13), mainly because hypomanic symptoms frequently fail to cluster in the way presumed by the diagnostic criteria that are drawn from our concept of manic episodes. Akiskal and Pinto

(14) have claimed that there is a substantial proportion of unipolar patients whose mood disorder shows bipolar affinity and that such patients occupy a large terrain between the extremes of classic unipolarity and bipolarity. To address this diagnostic conundrum, he and his colleagues have proposed a number of discrete syndromes characterized by decreasing severity of mania/hypomania under a rubric of “bipolar spectrum.” We agree with Akiskal and Pinto that there are large numbers of so-called unipolar patients who exhibit mild hypomanic symptoms; however, we argue that the field would benefit from a unitary and continuous approach to the assessment of both manic/hypomanic and depressive symptoms. On the basis of this unitary conceptualization of mood disorders, we hypothesized that patients with recurrent major depression without discrete lifetime hypomanic episodes would nonetheless report lifetime hypomanic/manic symptoms and that the number of lifetime hypomanic/manic symptoms would be related to the number of lifetime depressive symptoms. Finally, we hypothesized that manic/hypomanic symptoms would be associated with indicators of greater severity of depression.

We tested these hypotheses in 223 patients with mood disorders who were administered a structured clinical interview for the spectrum of mood disorders

(15). This instrument focuses on lifetime manic and depressive symptoms, traits, and lifestyles that characterize threshold and subthreshold mood episodes and “temperamental” features related to affective dysregulation.

Results

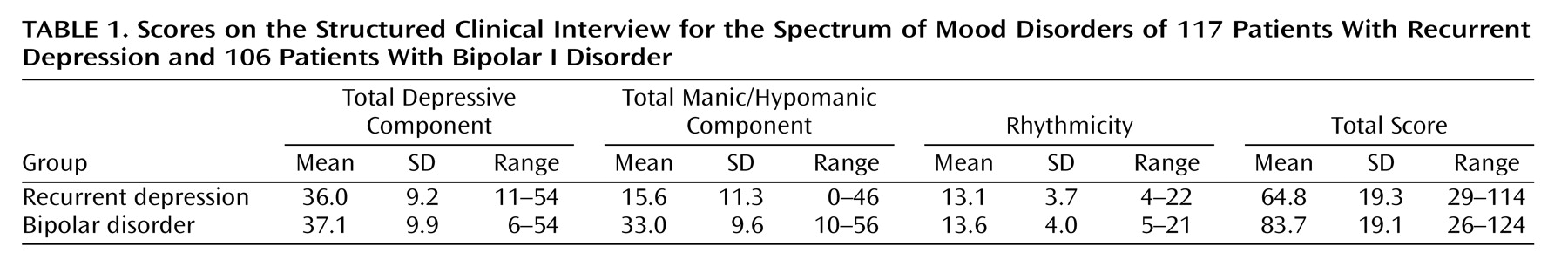

The mean number of mood spectrum items endorsed by the patients with recurrent unipolar depression and the patients with bipolar I disorder was 64.8 and 83.7, respectively (maximum=140) (

Table 1). The frequency distribution of the depressive component was essentially overlapping and normal in the recurrent unipolar depression patients and the bipolar I disorder patients, while the frequency distribution of the manic/hypomanic component was normal among the bipolar patients and significantly skewed to the right among the patients with recurrent unipolar depression (Kolmogorov-Smirnov test=1.4, p=0.03).

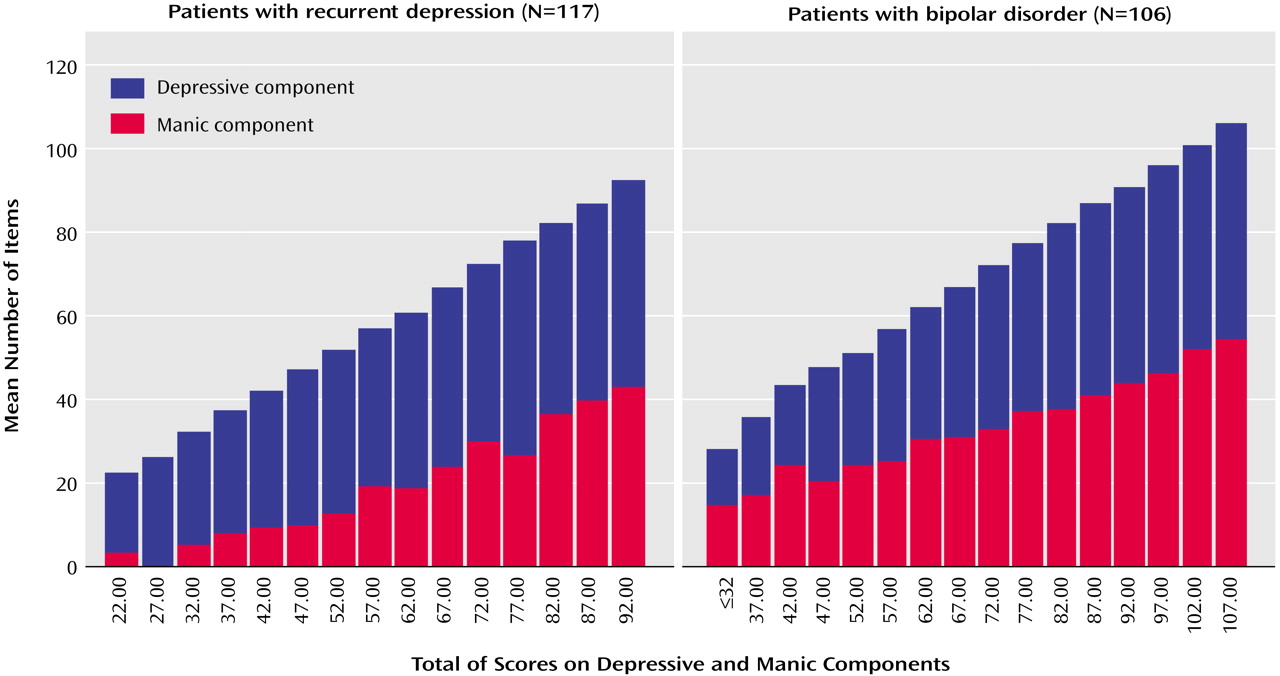

The correlation between lifetime depressive and manic component scores was similar in the bipolar I disorder (r=0.45, p<0.001) and recurrent unipolar depression (r=0.40, p<0.001) patients. An alternative way to show this relationship is to plot the mean depressive and manic component scores versus the depressive-plus-manic score. As the latter increases, the two components increase almost linearly, both in patients with bipolar I disorder and in patients with recurrent unipolar depression (

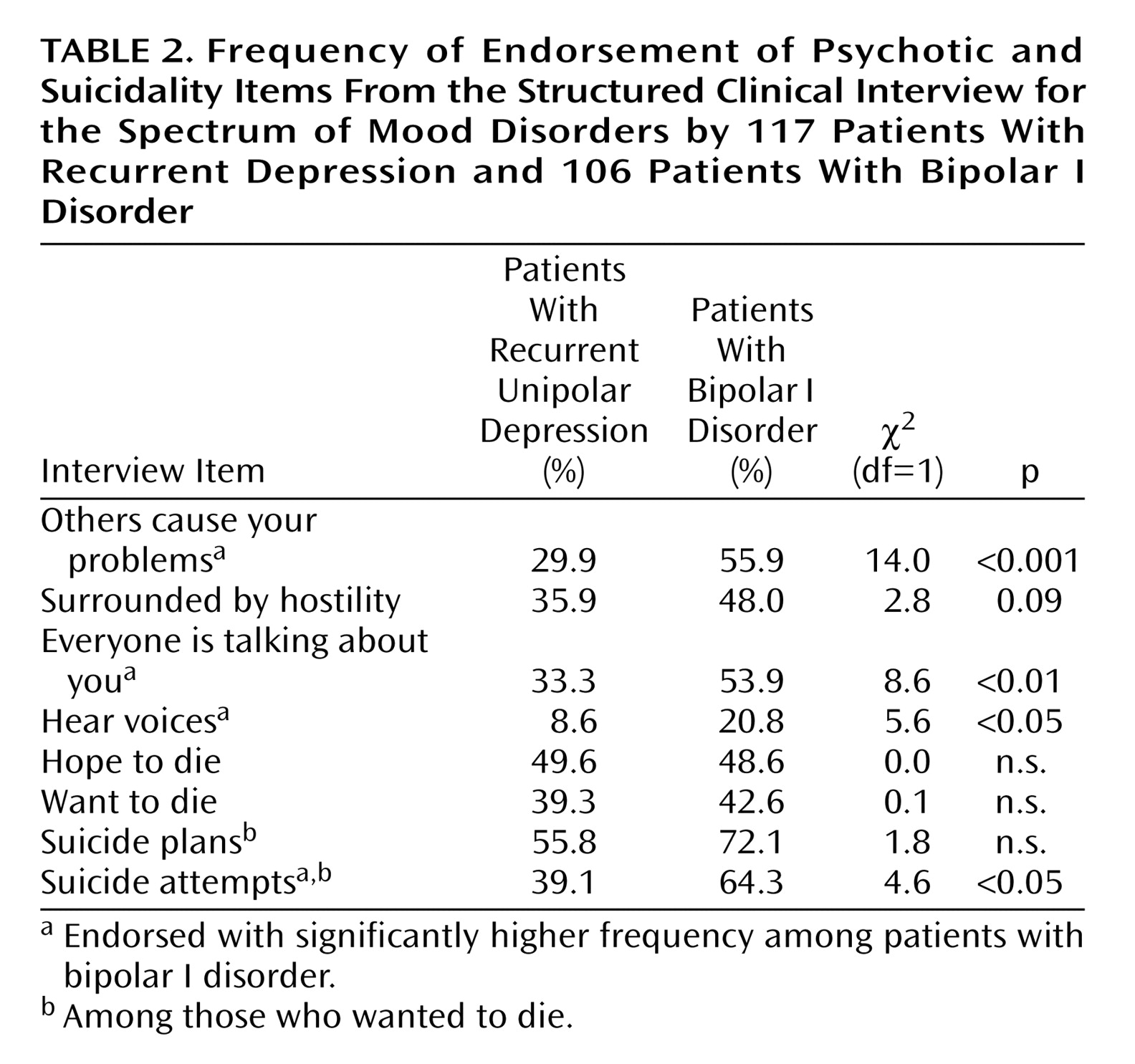

Figure 1). Thus, the number of depressive items endorsed, measured on a continuum, is related to the number of manic/hypomanic items endorsed. To further explore this issue, we selected psychotic and suicidality items as indicators of the severity of depression in the Structured Clinical Interview for the Spectrum of Mood Disorders. Four of these indicators, including paranoid ideation, auditory hallucinations, and suicide attempts, were significantly more common in the lifetime experience of patients with bipolar I disorder than in the patients with recurrent unipolar depression (

Table 2). We investigated the relationship between the number of manic/hypomanic items and these indicators of the severity of depression separately in the groups with recurrent unipolar depression and bipolar I disorder by using logistic regression models. To this purpose, we combined the four indicators of suicidality and the four indicators of paranoid ideation into two composite indicators and then dichotomized these indicators as no/any symptom of suicidal ideation and no/any symptom of paranoid ideation.

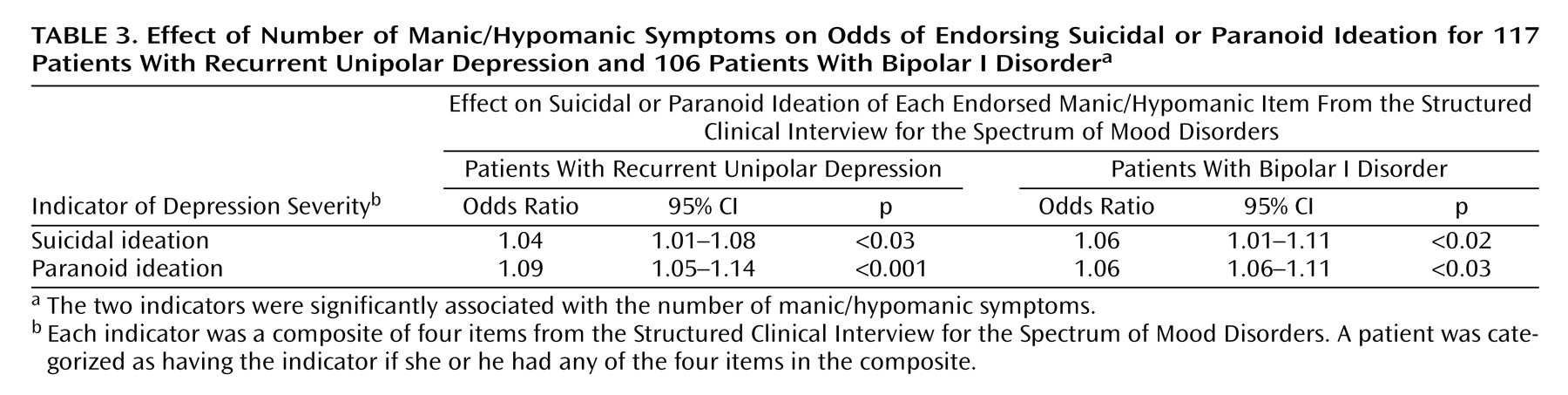

In the group with recurrent unipolar depression, the number of manic/hypomanic items was related to an increased likelihood of paranoid and suicidal ideation (

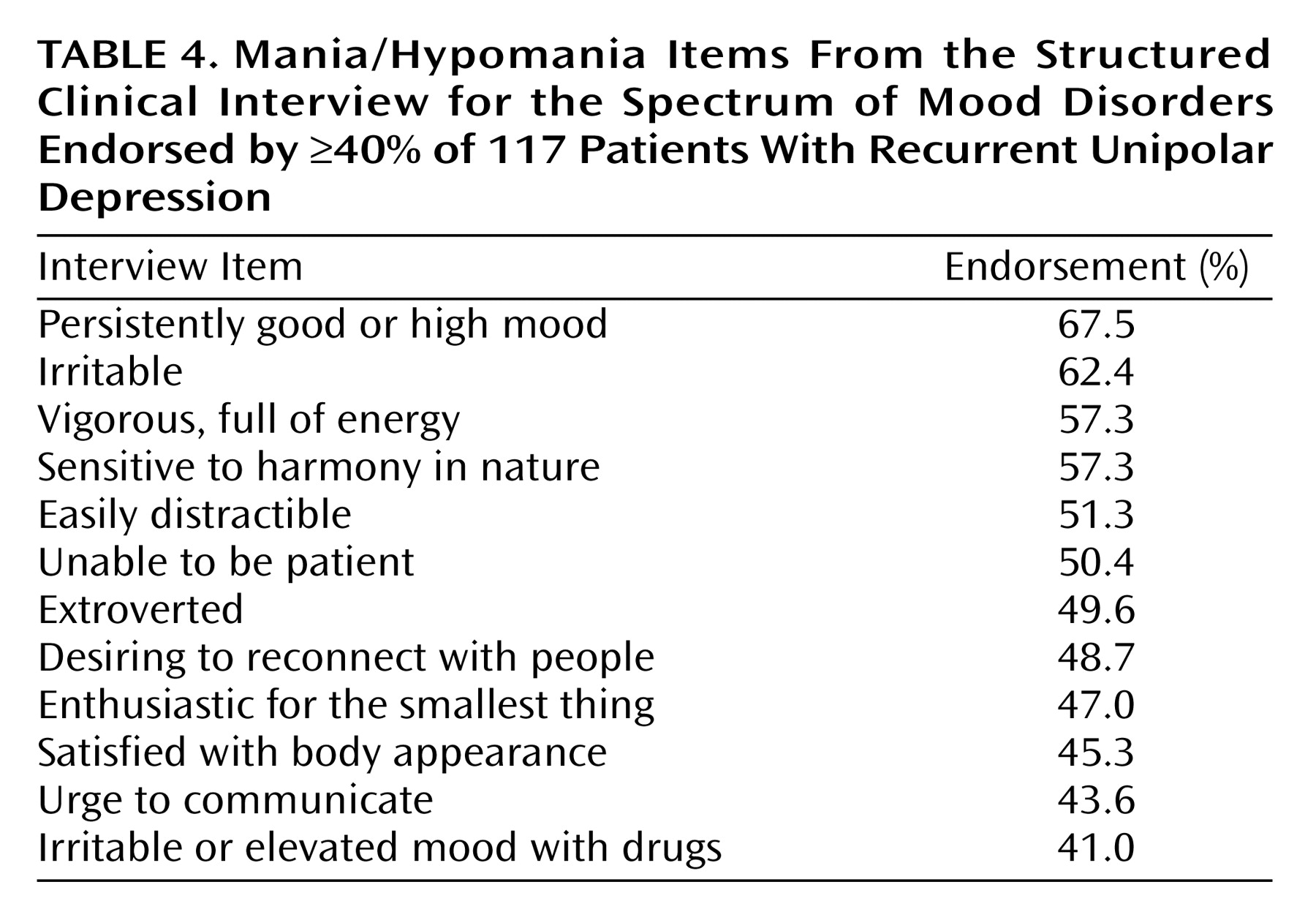

Table 3). For example, we found that for each manic/hypomanic item endorsed, the likelihood of suicidal ideation was increased by 4.2% (odds ratio=1.042, 95% confidence interval 1.006–1.079, p<0.03). This odds ratio corresponds to a 42% increase in risk of suicidal ideation for a 10-item difference in the number of manic/hypomanic symptoms endorsed. Consistent with this result, we found that even the current level of suicidal risk (coded as none, low, moderate, or high in the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview) increased significantly with the number of lifetime mania/hypomania items endorsed (ANOVA: F=3.8, df=2, 114, p<0.03). Moreover, an earlier onset of the first depressive episode was significantly correlated with a higher number of manic/hypomanic items (r=–0.32, p<0.01). Neither gender nor the number of depressive episodes was related to the number of manic/hypomanic items endorsed, the number of depressive items endorsed, or the total score on the Structured Clinical Interview for the Spectrum of Mood Disorders. To characterize the profile of manic/hypomanic features endorsed by the patients with recurrent unipolar depression, we summarized the 12 items endorsed with a frequency equal to or higher than 40% by the patients with recurrent unipolar depression (

Table 4).

In bipolar I disorder patients, the number of lifetime manic/hypomanic items endorsed was related to the endorsement of lifetime experiences of paranoid ideation and suicidal ideation (

Table 3). The number of lifetime depressive episodes was

not associated with the number of manic/hypomanic items endorsed, the number of depressive items endorsed, or the total score on the Structured Clinical Interview for the Spectrum of Mood Disorders. Women endorsed more depressive spectrum items than men (mean=39.1, SD=9.9, versus mean=34.9, SD=9.6) (t=2.2, df=100, p<0.05).

Discussion

We investigated the lifetime mood spectrum characteristics of a large group of patients with recurrent unipolar depression or bipolar I disorder by using the Structured Clinical Interview for the Spectrum of Mood Disorders. Symptoms such as paranoid ideation, auditory hallucinations, and suicide attempts were significantly more frequent in bipolar patients than in unipolar patients, which is in line with findings from the literature

(17).

Of note, there was a linear relationship between the number of lifetime manic/hypomanic items and the number of depressive items endorsed by both the patients with bipolar I disorder and those with recurrent unipolar depression. In addition, in the patients with recurrent unipolar depression, the more manic/hypomanic items endorsed, the greater the likelihood of reporting suicidal ideation and delusions. This latter result corroborates the observation that the presence of even mild manic symptoms may change a depressive presentation into a mixed presentation and increase the likelihood of psychotic symptoms

(18). Our results, indicating that the number and severity of depressive features experienced by any given mood disorder patient are related to the extent of the manic/hypomanic symptom that he or she has experienced in his or her lifetime, are in line with those of Goldberg et al.

(19). They also reported that by the 15-year follow-up, 27% of the patients hospitalized for unipolar major depression eventually developed one or more distinct episodes of hypomania, and 19% had at least one episode of mania. They also showed that patients with psychotic depression are more likely than nonpsychotic patients to develop subsequent mania or hypomania at follow-up.

Although psychotic symptoms were more common in the patients with bipolar I disorder, the endorsement of symptoms such as “feeling as if others were causing all of your problems,” “feeling surrounded by hostility,” and auditory hallucinations were related to increasing levels of mania/hypomania both in recurrent unipolar depression patients and in bipolar I disorder patients. In recurrent unipolar depression patients, an earlier onset of illness was associated with a higher frequency of endorsement of manic/hypomanic symptoms, which confirms our expectations based on the present literature

(20). Although this latter result seems to foreshadow that among patients with recurrent unipolar depression, an increasing number of manic/hypomanic symptoms correlates with a higher risk of recurrences, we did not find such an association. One explanation for this seemingly paradoxical finding is the range restriction in the number of depressive episodes (median=3) in the study group, resulting from the conservative inclusion criteria we adopted. Indeed, we selected patients with two or more depressive episodes and no hypomanic episodes, therefore excluding patients with single episodes and bipolar II patients. Still, evidence from a study contrasting a large group of patients with pure unipolar depression, hyperthymic unipolar depression, bipolar I disorder, and bipolar II disorder

(21) indicates that the number of depressive episodes is not significantly increased in patients with hyperthymic unipolar depression (mean=4.1) versus pure unipolar depression (mean=3.7).

Cumulatively, our empirical findings support a continuous view of the mood spectrum as a unitary phenomenon that is best understood from a longitudinal perspective. Our data suggest that unipolar disorder and bipolar disorder are not two discrete and dichotomous phenomena but that mood fluctuations—up and down—are common to both conditions, as emphasized by Koukopoulos et al.

(22). Indeed Swann

(23), espousing the parsimonious Kraepelinian view, conceptualized recurrent affective disorders as one illness in which the apparently different bipolar and unipolar course may be determined by increased sensitization after the occurrence of a manic episode. Using a different term, Ghaemi et al.

(7) proposed a view of the “affective spectrum” that spans the single depressive episode and bipolar I disorder to accommodate nonclassical parts of the bipolar spectrum, such as type II, not otherwise specified, and cyclothymia.

The implications of a unitary approach to mood disorders are not only nosographic. We believe that clinical attention should be paid to sporadic manic/hypomanic manifestations in treatment planning and the prognosis of recurrent unipolar depression. Our data suggest that manic/hypomanic features, as Judd and Akiskal

(24) have argued, are not “benign” because they are associated with increased lifetime and current suicidality. Our findings are in line with the results of their recent reanalysis of Epidemiologic Catchment Area data that also emphasize how even subsyndromal manic symptoms are associated with increased service use for mental health problems and the need for welfare and disability benefits. However, it must be acknowledged that only a long-term prospective follow-up study of patients assessed with the Structured Clinical Interview for the Spectrum of Mood Disorders early in their course of illness could confirm the utility of this kind of evaluation.

The present study has a number of limitations. First, the Structured Clinical Interview for the Spectrum of Mood Disorders does not provide information on the frequency of occurrence of individual symptoms but only inquires whether symptoms did or did not occur for a period of at least 3–5 days in the subject’s lifetime. Thus, the relationship we found between the number of manic/hypomanic and depressive items does not imply anything about the co-occurrence or sequence of these experiences. Also, given that the instrument assesses symptoms and behaviors retrospectively, there might be a recall bias. In this article, we assumed that the bias does not differentially affect the recall of manic/hypomanic and depressive spectrum features. Finally, caution should be used in interpreting the results because of their preliminary nature. Further analyses conducted on separate samples since the submission of this article confirmed all of the findings we report here.