Initially described in wartime combatants, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is recognized as a common health problem associated with exposure to traumatic events such as natural catastrophes, motor vehicle accidents, assault, rape, and robbery

(1,

2). Research over the past 15 years has also examined the psychological impact of terrorist acts such as hostage-taking, bombings, and shootings, but mainly in the short term

(3–

14). Estimates of the prevalence of PTSD after terrorist attacks range from 7.5% to 50% in the year after the event depending on the degree of victimization. Despite the increase in terrorist attacks worldwide, there is less evidence about the intermediate and long-term psychological consequences of terrorism, in particular PTSD, or about risk factors

(5,

15–18). Studies of individuals incurring physical injuries should also be considered in addressing the long-term consequences of traumatic events. Research on victims of motor vehicle accidents shows a higher risk of PTSD, at rates that vary between 11% and 46%, 1–5 years postaccident

(19,

20). While few studies have evaluated the long-term prevalence of PTSD among burn victims, it appears to fall between 22% and 45% after 1 year and has been reported to be higher after discharge than during hospitalization

(21,

22).

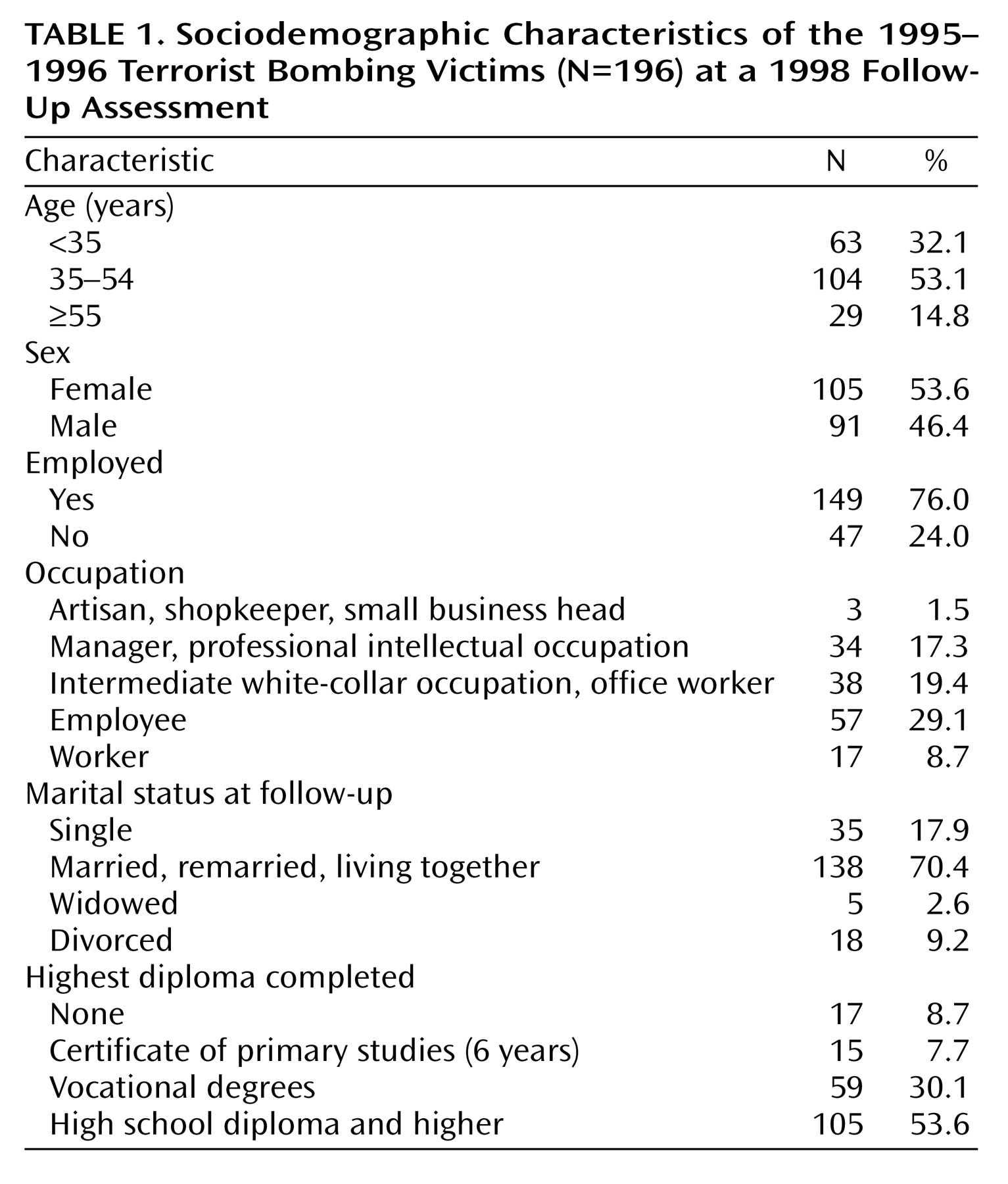

Between July 25, 1995, and December 3, 1996, a wave of bombings attributed to Islamist fundamentalist networks hit France. Six struck Paris, and one struck the Lyon region; most occurred in metro stations. Twelve people were killed. Approximately 450 people applied for compensation from the French Terrorism Victim Guarantee Fund, a public guarantee fund to provide immediate financial aid and indemnification for health consequences and long-term sequelae. In 1998, we carried out a retrospective, cross-sectional epidemiologic study of terrorist bombing victims to evaluate the prevalence of and factors associated with PTSD.

Discussion

This study surveyed 196 terrorist bombing victims (86% of eligible respondents), a relatively high number compared with most other studies focusing on the intermediate- and long-term psychological consequences of terrorist attacks

(15,

16,

18,

29). According to the French Terrorism Victim Guarantee Fund, this group included almost all people injured during the 1995–1996 bombings.

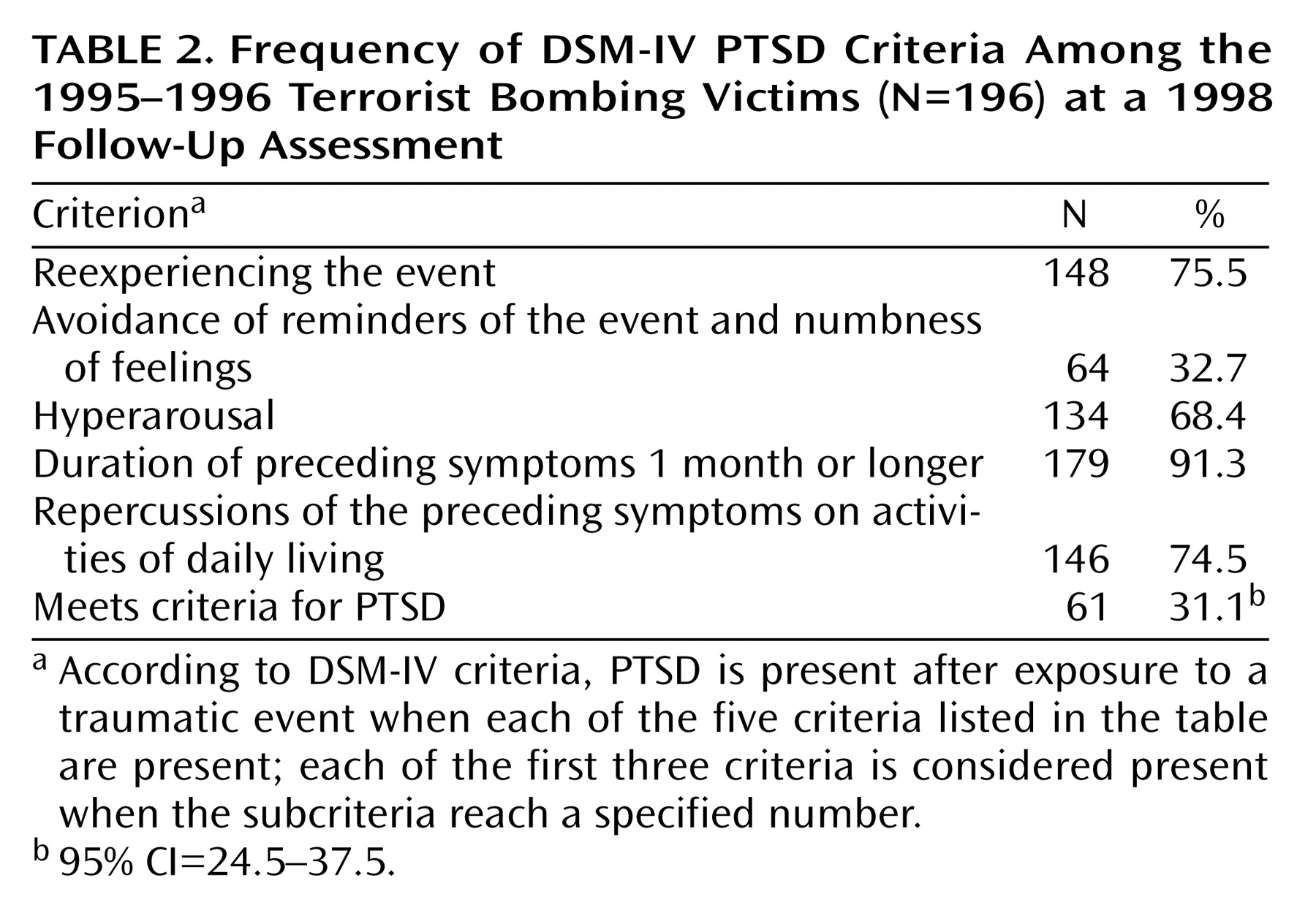

The overall prevalence of PTSD was high (31.1%) at a mean of 2.6 years (SD=0.6) after the event. Comparisons with other studies focusing on intermediate- and long-term psychological consequences of terrorist attacks are difficult because of differences between populations, study methods, and measures

(15,

16,

18,

29). However, the prevalence of PTSD was higher than the 18.1% prevalence rate in a study of victims of bombings between 1982 and 1987 in France

(17). Most studies report that the prevalence of PTSD after a traumatic event decreases over time. Moreover, in a study of PTSD subjects 15 to 54 years of age in the U.S. general population, the median time to remission was 64 months in people who were not treated and 36 months in those who received treatment

(1). One-third of respondents did not have a single remission in the 10 years following the onset of PTSD.

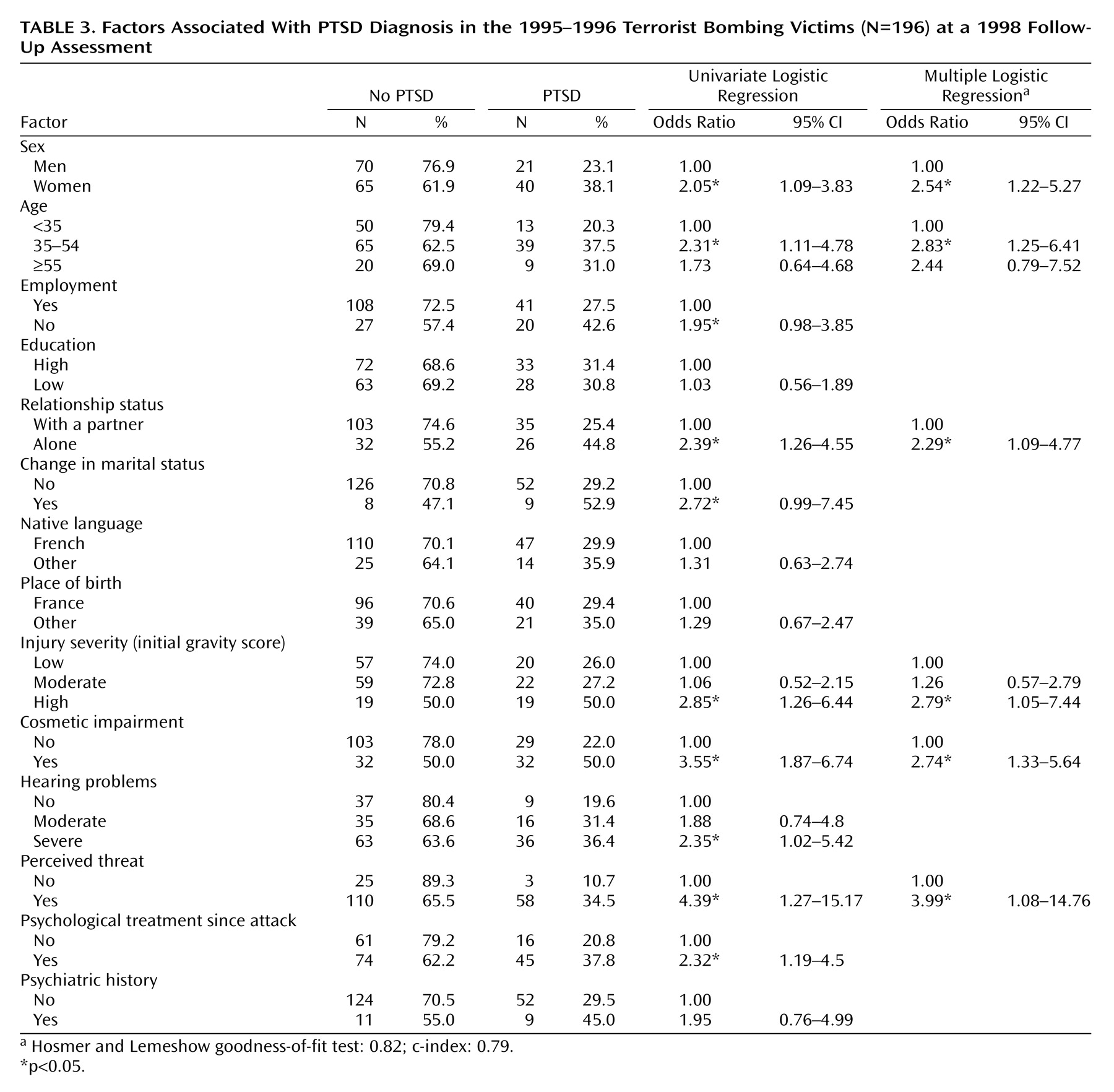

Our findings show a significant relation between injury severity and PTSD prevalence at a follow-up evaluation 2.6 years after the attacks. A relation between the nature and severity of injuries (including burns) and PTSD is reported only inconsistently. Some studies observe no such relation

(3,

22,

30–33)—these authors stress instead the prominent role of subjective perception of stressors in mediating the development of PTSD. Others state that the severity of physical injury is one of the most reliable predictors of PTSD

(10,

17,

34–36). Two hypotheses have been proposed. Solomon

(34) hypothesized that more severe injuries may be associated with a more traumatic initial reaction that is also predictive of a PTSD that progresses more rapidly and lasts longer. Others have suggested that results may depend on the length of time elapsed since the accident, with extent of injury becoming a more important predictor over time

(35); long-term disability due to severe injury serves as a constant reminder of the trauma and thereby tends to extend the duration of PTSD.

Our finding of an association between cosmetic impairment and PTSD is similar to the findings in a study of Japanese burn patients, which found that facial disfigurement was associated with PTSD only among women

(29). This difference may be due to cultural differences or to the methods used to assess physical sequelae (clinical examination in the study by Fukunishi

[29], self-report in ours). Cosmetic impairment may constantly remind the victims of the traumatic event, which may explain the poorer long-term adjustment and greater distress than for other respondents. Nonetheless, negative appraisal of cosmetic impairment may also be associated with the presence of depressive or PTSD symptoms that may increase patients’ focus on threats to their self-image

(21). Our study design did not allow us to confirm a causal relation between PTSD and cosmetic impairment, but it raises a novel and potentially quite important hypothesis regarding this risk factor, which deserves further research.

We also found a higher prevalence of PTSD among respondents with moderate and mild injuries (27.2% and 26.0%, respectively) compared with the general population

(1). This suggests that factors other than those associated with physical trauma, such as perceived threat, may play a role in the development of PTSD. The highest odds ratio (3.99) was found between perceived threat and PTSD; this result is supported by studies showing that factors such as the threat of death or the viewing of mutilated bodies are associated with the onset of PTSD

(2,

37).

Our finding of a higher prevalence of PTSD in women is supported by results from several studies

(1,

38–41). There is mixed support in the literature for our finding of an association between age and PTSD

(40,

42,

43), although several studies have observed an increased risk of PTSD in 35–54-year-olds during natural catastrophes

(43–

45). These findings may be explained by the substantial economic consequences experienced by respondents with PTSD in this age group.

Failure of prior psychiatric history to be a strong predictor of PTSD may be related to the proxy variables used, which did not allow a thorough reconstruction of the nature and severity of past psychiatric disorders. It might also result from insufficient statistical power: relatively few subjects reported a past history of psychiatric disorders (11 subjects without and nine with PTSD).

The main limitation of this study is its retrospective design. The psychological consequences of the terrorist bombings were assessed through retrospective self-reports. Respondents’ recollections of the attack and its sequelae may have been influenced by their psychological state at follow-up

(37,

46). However, it is unlikely that respondents overreported PTSD symptoms to seek financial gain. Participants were aware that all information they provided was confidential and would not be passed on to the French Terrorism Victim Guarantee Fund. They had already been recognized as victims and entered into the indemnification process by the French Terrorism Victim Guarantee Fund at the time of the study.

We have restricted our study to those who were directly exposed to the bombings; because of the high response rate, reconstruction of this group was substantially complete. Victims who were not directly exposed were excluded. It is very difficult to predict the consequence of this exclusion on the estimate of PTSD prevalence, since PTSD, perhaps less severe, may also occur in these subjects. Because our comparisons involved subjects with relatively similar experiences, the odds ratios associated with injury severity, cosmetic impairment, and perceived threat may be underestimated.

In conclusion, few studies have evaluated the long-term prevalence of PTSD several years after terrorist attacks. We surveyed a large sample of victims (N=196), evaluated psychological outcomes a mean of 2.6 years after the 1995–1996 attacks with rigorous measures, and found a high prevalence of PTSD in injured victims. Our findings suggest that psychological care for some victims may have been inadequate in the 2–3-year period after the event and thus highlights the need for improved health services to address the intermediate and long-term physical, psychological, and social consequences of terrorism. Risk factors associated with PTSD that may help to identify those at highest psychological risk include female gender, severe initial injuries, and high perceived threat. Finally, results suggest the role of cosmetic impairment in the persistence of PTSD.