The Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks served as a grim natural experiment in how an unexpected, unpredictable, and frightening series of events affect the psyche of a country and its citizens. In the weeks after the attacks, national surveys described high levels of stress and anxiety

(1–

3), which, for New Yorkers, were followed by reports of elevated levels of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

(4–

6), depression

(7), and substance use

(8). Early assessments predicted that more than 500,000 individuals in the New York City area alone would develop PTSD

(9), and national public health leaders worried that that the psychological sequelae of these attacks could overwhelm the country’s mental health system

(10).

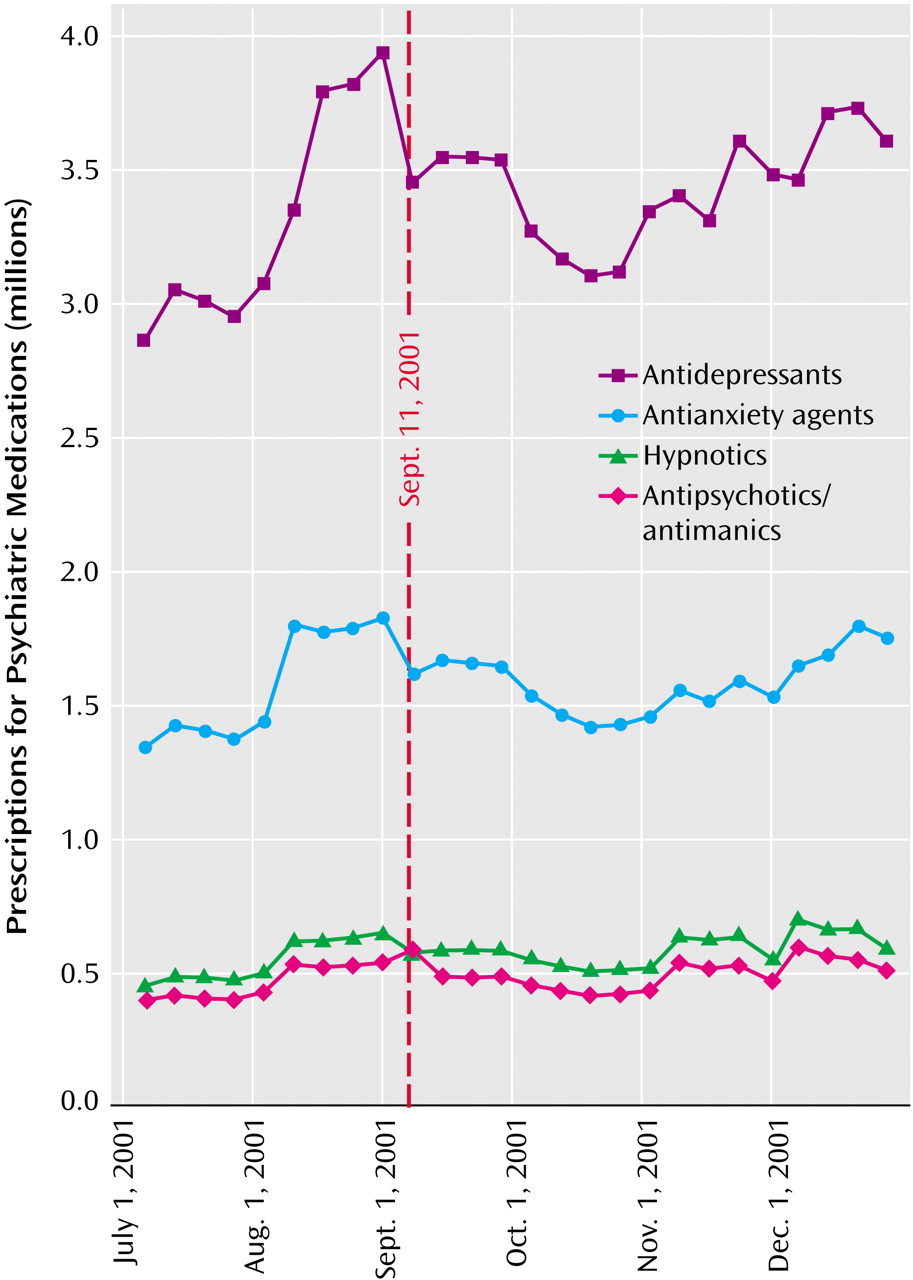

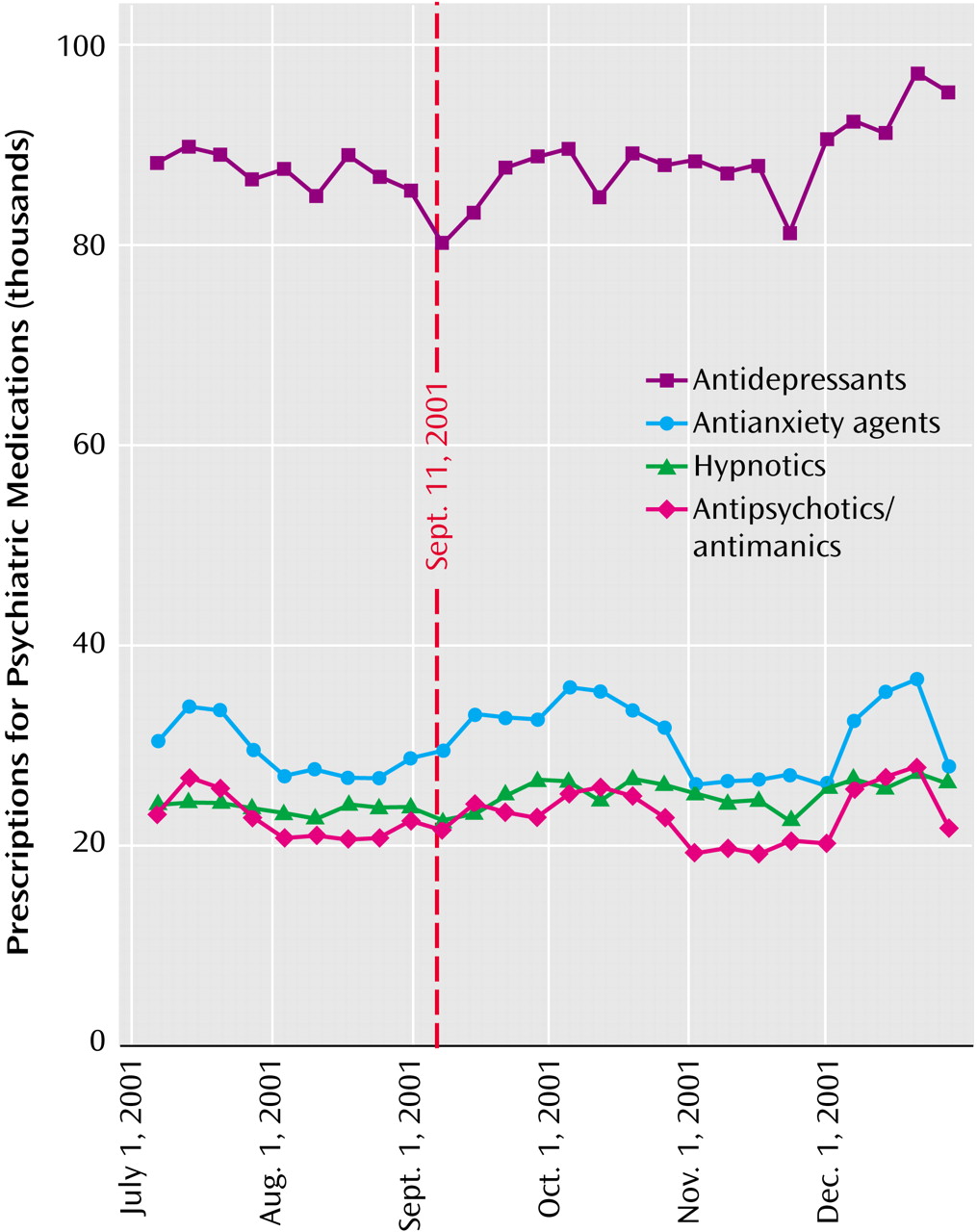

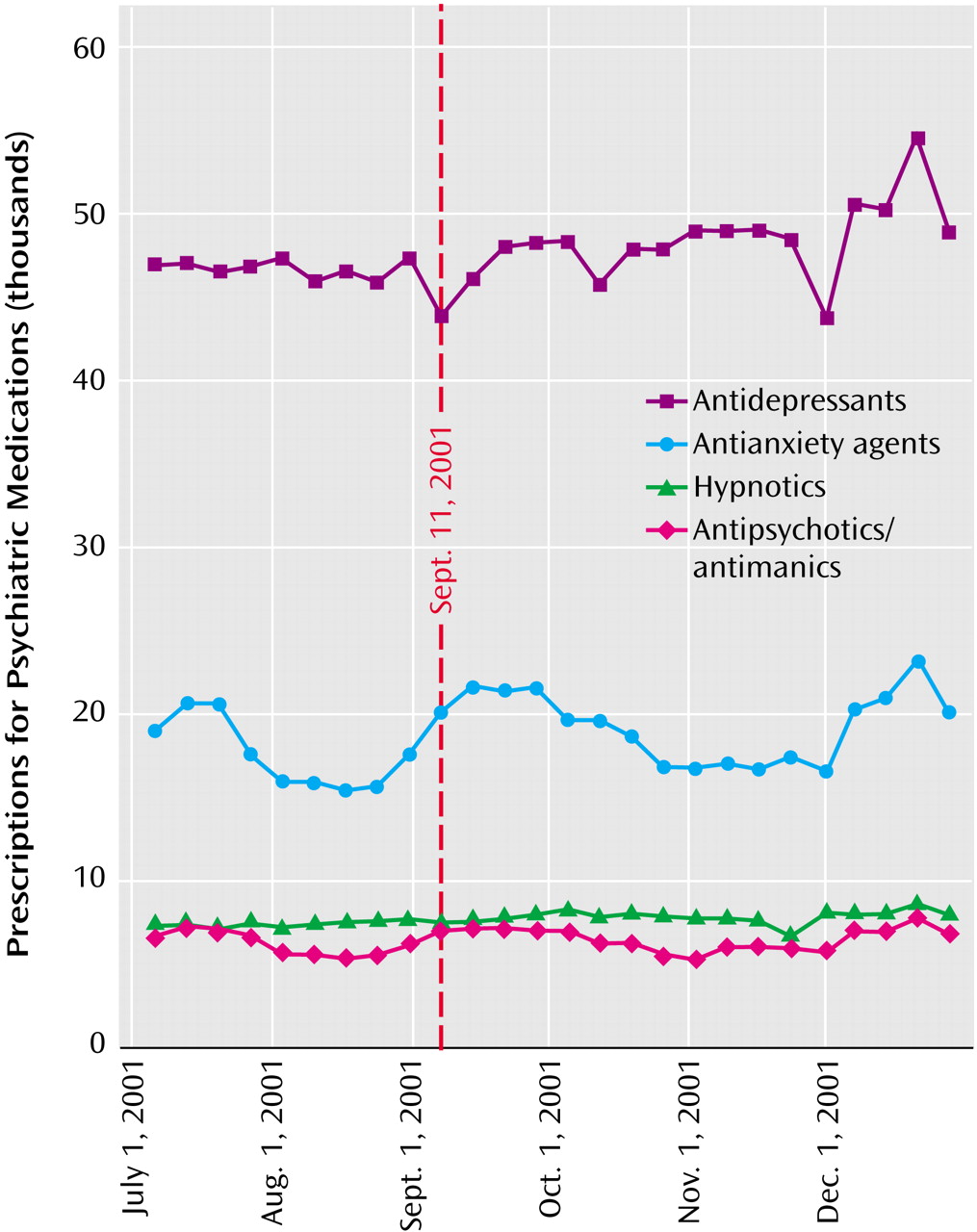

This study seeks to better understand how Americans coped with these attacks by examining changes in the use of psychotropic medications in the weeks following Sept. 11, 2001. Did the shock and distress following the attacks lead to increased use of psychoactive medications? If so, did this occur nationally or only in New York City, where the majority of the attacks occurred? And, if not, what does it say about Americans’ help-seeking behavior after the attacks?

Discussion

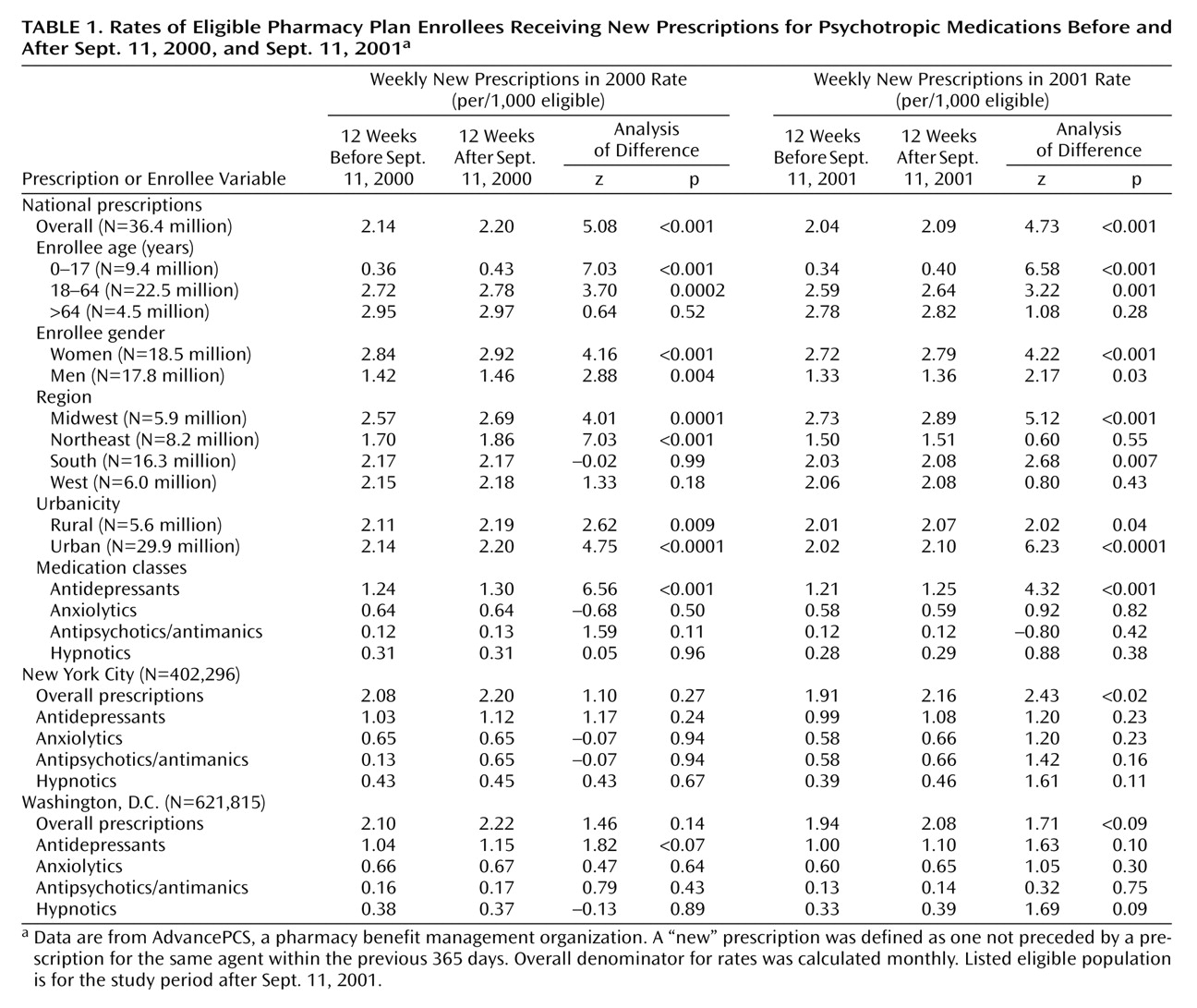

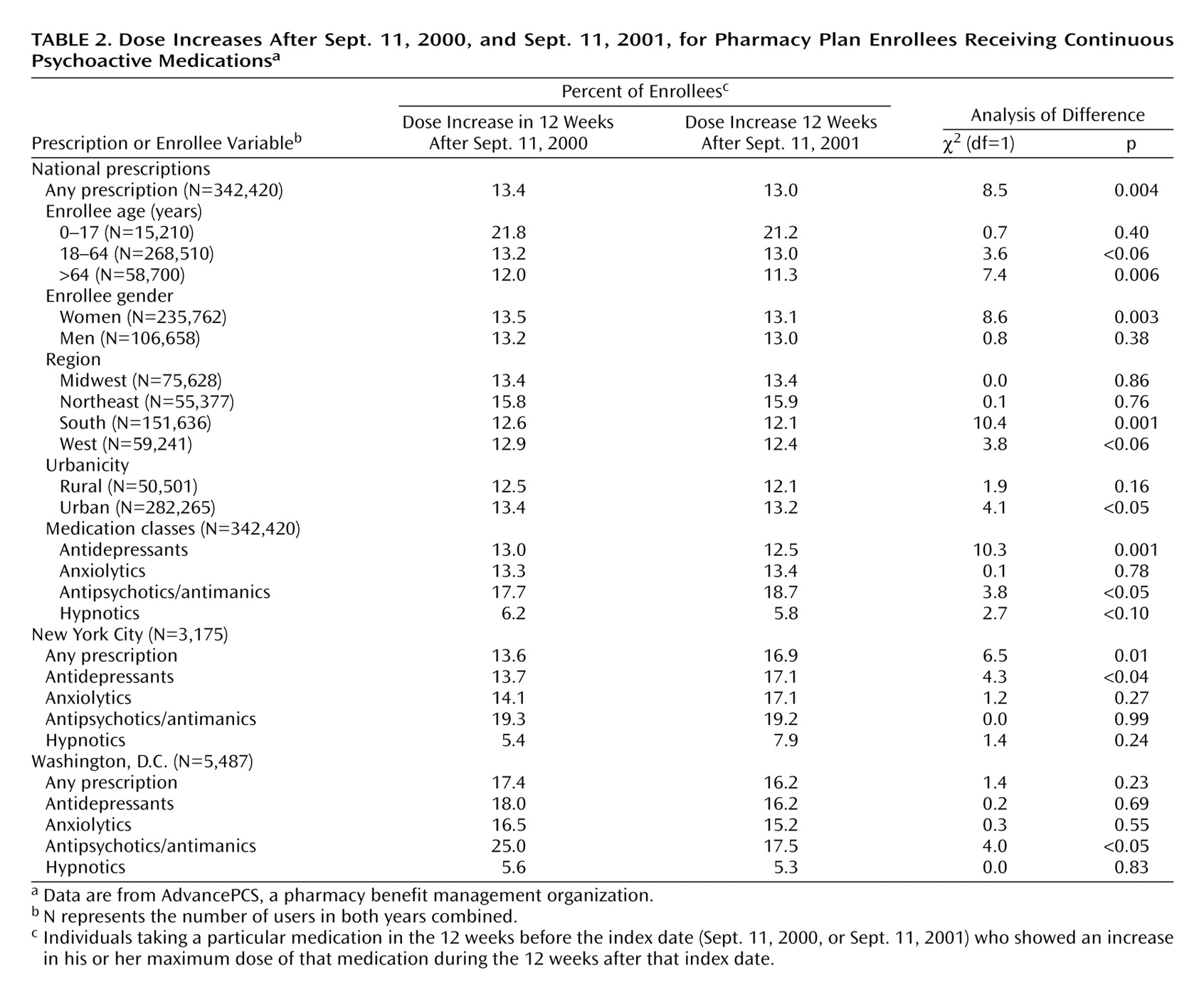

In the general population, the acute shock and fear of the events of September 11 were not accompanied by a commensurate increase in the use of psychotropic medications. However, for certain subpopulations—in particular, certain subgroups of patients already taking psychotropic medications—there was a small but consistent increase in the use of these medications. Understanding Americans’ help-seeking behavior after these events thus requires a consideration of each of these findings—both the general lack of an increase in use among Americans as a whole and the factors conferring vulnerability to those subgroups.

The current study’s findings confirm and expand on earlier reports finding little or no increase in the use of formal mental health services after the attacks. Those studies found no increase in managed behavioral health care

(18), military

(19), or U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs

(20) mental health service use, even among patients with preexisting PTSD and other mental conditions

(21). A study of prescriptions filled by employees of two companies found a transient increase in the use of antianxiety medications but not for other categories of psychotropic drugs in the weeks following the attacks

(22).

Taken together, this evidence suggests that initial predictions of a drastic increase in mental health service use after September 11 were not realized. There are several possible explanations for this negative finding. First, it is possible that patients who needed care failed to obtain access to it. The weeks after September 11 were followed by an unprecedented infusion of public and private funds for mental health treatment, as well as campaigns encouraging the public to use those resources

(23,

24). However, other barriers, including stigma, lack of insurance coverage, or the chaos imposed by the events of September 11 themselves, may have prevented individuals from obtaining needed services.

Second, it is possible that many individuals, while symptomatic, did not see themselves as needing formal mental health treatment. A decision to seek mental health services, or any health services, typically involves not only symptoms but also the perception that they are a problem that requires treatment

(25). In the aftermath of the terrorist attacks, many Americans may have regarded their distress as a “normal” reaction to these unprecedented events that was shared with their neighbors and communities rather than as a disorder needing care.

Finally, many people are likely to have sought help through friends and family, local communities, or clergy. These informal services, along with debriefing and counseling services specifically put in place after the September 11 attacks (e.g., New York’s Project Liberty), would not be captured in claims databases.

Nationally, the only group with an increase in psychotropic prescriptions after the September 11 attacks was patients already being treated with antipsychotic medications. This is consistent with previous research indicating the psychological vulnerability conferred by preexisting psychiatric disorders after traumatic events. More than half of the individuals with PTSD resulting from the Oklahoma City bombing met criteria for a psychiatric disorder before the incident

(26), and the presence of a preexisting diagnosis of a mental disorder was a strong predictor of attack-related distress after Sept. 11, 2001

(27,

28). Indeed, the presence of a preexisting psychiatric disorder is one of the factors most consistently found to predict PTSD after traumatic events

(29,

30). Patients with schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders may be the most vulnerable group of all; even minor stressors may be enough to lead to exacerbations in this population

(31).

In New York, a modest but consistent increase in dose was seen among existing users of psychotropic medications. This finding is consistent with epidemiological reports that the degree of attack-related distress was inversely proportional to the distance from where the attack occurred

(1,

4). New Yorkers were more likely than the rest of the nation either to be directly involved in the attacks or to have family, friends, or acquaintances who were affected. In contrast, most Americans who lived outside of New York City primarily experienced the attacks indirectly. Vicarious exposure to traumatic events, while stressful, may differ both quantitatively and qualitatively from more direct forms of trauma

(32).

The study’s findings should be interpreted in the context of several important limitations. The data sets had considerably more breadth than depth; they did not include mental health diagnoses, other important clinical data, or information on treatments other than pharmacotherapy. Second, some individuals might have had delayed onset of symptoms or treatment-seeking that did not emerge until after the 3-month follow-up period. Clinically, such delayed responses appear to be relatively rare

(26,

33). Methodologically, it would be difficult to establish whether any changes in psychotropic medication occurring after the first several months had any causal connection to the terrorist attacks.

The study’s findings are consistent with epidemiological surveys indicating that the distress associated with the September 11 attacks was more transient and self-limited than had originally been anticipated. Nationally, the proportion of the population reporting depressive symptoms fell by more than half by the beginning of November 2001

(34), and most PTSD symptoms in New York City residents had resolved by 6 months after the attacks

(35). This apparent resilience may have been possible not so much in spite of, but rather because of, the breadth of their impact. Following the September 11 attacks, Americans reported an increased sense of connectedness to each other and their nation which was marked by rising volunteerism, greater involvement in local organizations, and a surge of patriotism

(36). Such a sense of community can provide a powerful healing force; for Americans, it may have helped provide a context for, and a means of coping with, the terrorist attacks.