Bereavement in children and adolescents has been associated with long-term psychological consequences, such as depression

(1–

14), anxiety

(12,

13), posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

(8–

10), behavioral problems

(13,

14), suicidal ideation

(15), and reduced psychosocial functioning

(16). Yet, less is known about the phenomenology and course of grief itself because of the lack of standardized criteria and the lack of use of standardized measures longitudinally over time. Thus, the boundaries between normal and complicated grief in children and adolescents are not well understood.

During the past decade, consensus has emerged that in bereaved adults, a syndrome of “traumatic grief” that is distinct from depression and anxiety is associated with long-term physical and mental health consequences

(17–

21). Individuals with traumatic grief show greater functional impairment, poorer physical health, and more suicidal ideation than those without traumatic grief, even after control for comorbid psychopathological conditions, such as depression and anxiety. Therefore, the entity of traumatic grief appears to capture an important and unique determinant of course, adaptation, and function after bereavement.

Most of our knowledge about normal and complicated grief comes from the study of conjugal bereavement in adults

(22–

25). Relatively little empirical work has been conducted on the phenomenology of grief in children and adolescents with any standardized assessments. In their study comparing suicidally bereaved to not suicidally bereaved children, Cerel et al.

(13) reported feelings of sadness, anxiety, anger, acceptance, and relief among the bereaved group. One of the few longitudinal studies of bereavement in adolescents examined the impact of adolescent suicide on peers and siblings. In this study, friends of adolescent suicide victims were compared to a nonbereaved matched adolescent comparison group. Previous publications have emphasized the psychiatric impact of bereavement, namely, increased rates of depression, anxiety, and PTSD in this bereaved cohort

(2–

10). A follow-up of a subgroup of the peers 6 years after the suicide documented the occurrence of traumatic grief, which was associated with suicidal ideation, even after control for depression

(15). However, the overall course of grief in this cohort was never described. In this article, we describe the symptoms and course of traumatic grief among adolescents exposed to their peer’s suicide. We also describe the relationship between traumatic grief and the two main psychiatric sequelae of exposure to a peer’s suicide, depression and PTSD, both cross-sectionally and longitudinally. We examine the likelihood of developing traumatic grief over time among subjects with and without these disorders; the comorbidity of traumatic grief with depression and PTSD; and whether traumatic grief predicts the onset or course of depression and PTSD.

Results

Symptoms and Course of Traumatic Grief

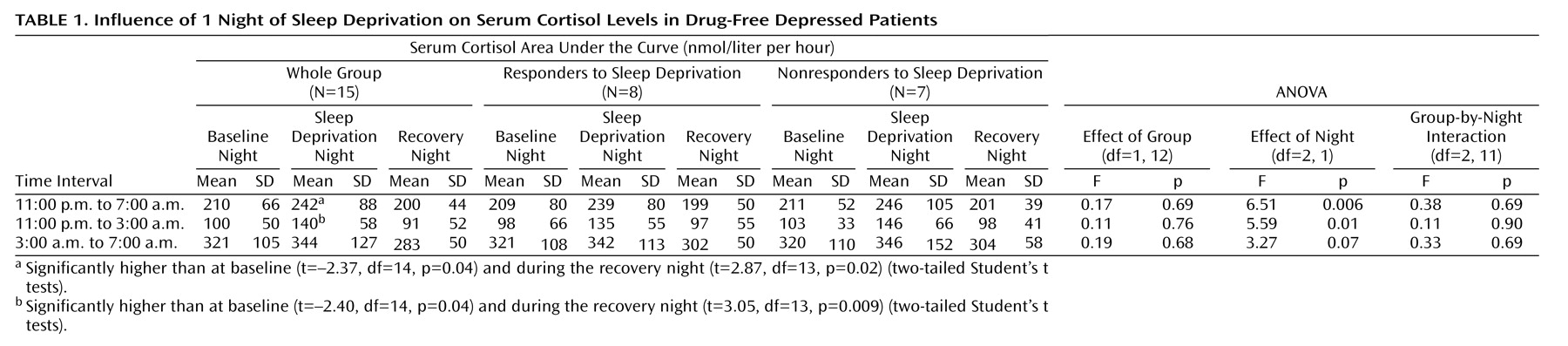

Principal component analysis on the Texas Revised Inventory of Grief resulted in two factors explaining 64.2% of the variance.

Table 1 presents the items loading on these factors. Factor 1, accounting for 35.5% of the variance, included items of crying, yearning, numbness, preoccupation with the deceased, functional impairment, and poor adjustment to the loss. The second component accounted for 26.7% of the variance. Factor analyses on 12–18-month and 36-month follow-up data resulted in similar two-factor solutions. Factors 1 and 2 appeared to be reliable, with internal consistencies of 0.923 and 0.849, respectively. The cluster of symptoms loading on factor 1 seems to reflect traumatic grief, whereas the symptoms loading on factor 2 seem to reflect another component of grief, more of a separation distress component.

The correlations between the scores on the traumatic grief factor at 6, 12–18, and 36 months after the suicide with scores on the Inventory of Complicated Grief administered 6 years after the suicide were 0.46 (p<0.001), 0.64 (p<0.001), and 0.72 (p<0.001), respectively.

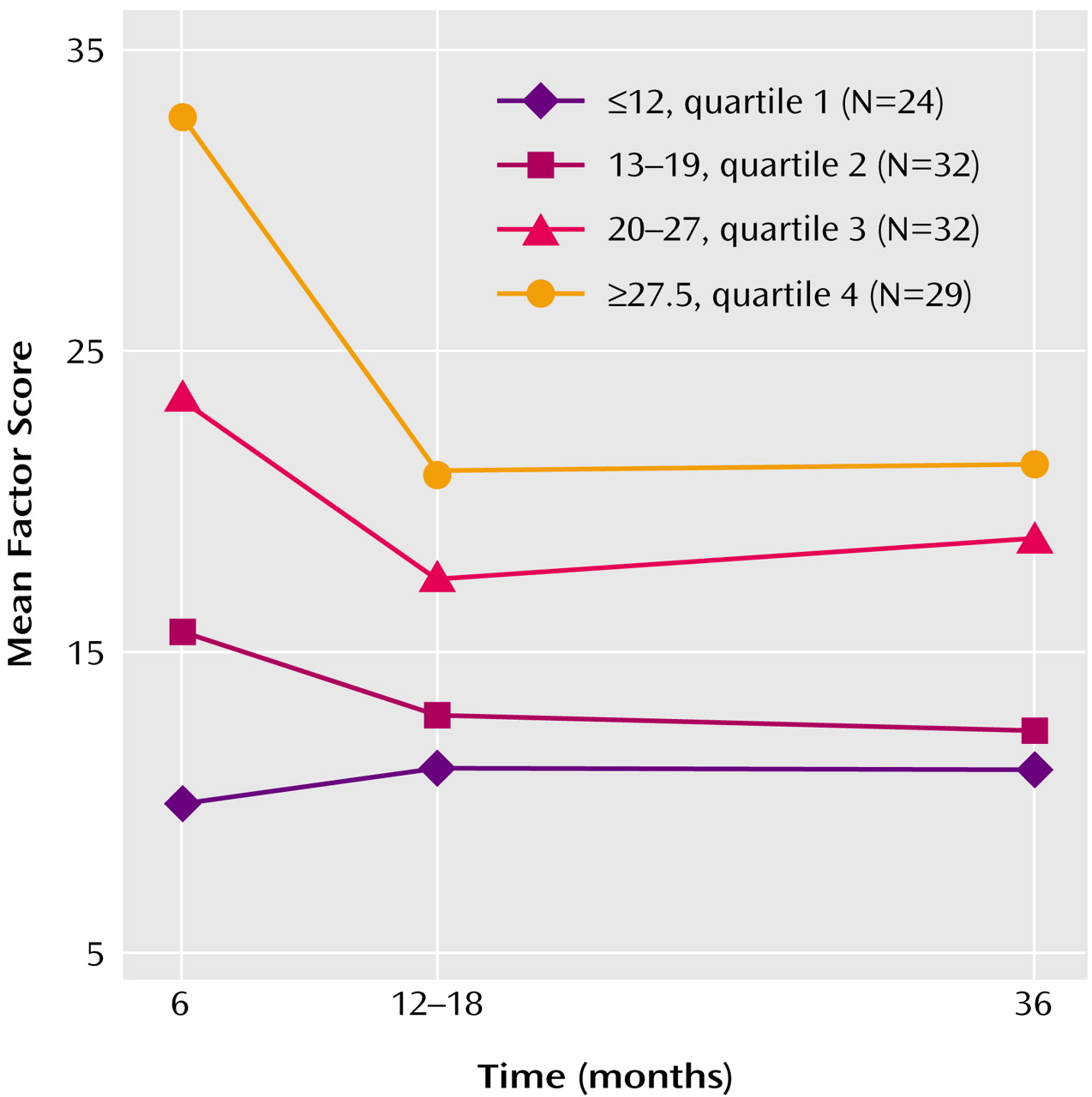

Mean scores on the traumatic grief factor decreased significantly at 12–18 months, after which no significant change was observed. This pattern was observed regardless of the initial severity of traumatic grief (

Figure 1).

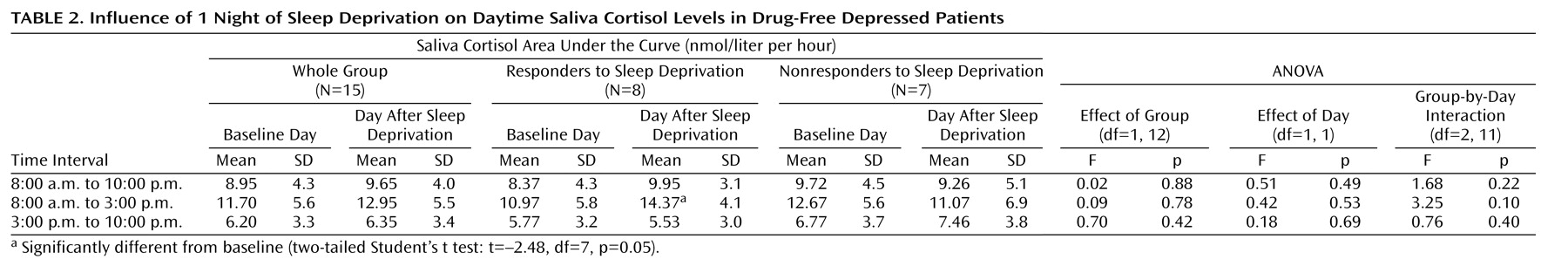

Traumatic grief was defined as scoring in the upper 25% of factor 1 at 6 months.

Table 2 presents the point prevalence of traumatic grief, depression, and PTSD at each assessment. For traumatic grief, cutoffs used for the quartiles at 6 months were applied to 12–18 and 36 months. Of the subjects who met our criteria for traumatic grief at 6 months (N=29), 13.8% (N=4) continued to meet criteria at the 12–18-month assessment, and 7% (N=2) continued to meet criteria throughout the entire follow-up period.

Traumatic Grief and Depression

The likelihood of developing traumatic grief was independent of depression. Of the subjects who were depressed within 1 month of exposure to suicide (N=59), 61% (N=36) continued to be depressed at 6 months. These subjects and those who were no longer depressed at 6 months were equally likely to meet criteria for traumatic grief at 6 months (50% versus 40%, respectively) (χ2=0.46, df=1, p=0.50). Similar results were found when following subjects who were depressed at 1 and 6 months to examine their likelihood of developing traumatic grief at 12–18 months (15% versus 7%, respectively) (p=0.60, Fisher’s exact test).

Among the subjects who met our criteria for traumatic grief, 44.8%, 40%, and 33.3% were also depressed at 6, 12–18, and 36 months, respectively. The correlations between scores on the traumatic grief factor and depression scores at 6, 12–18, and 36 months were 0.52 (p<0.01), 0.35 (p<0.01), and 0.27 (p<0.01), respectively.

Traumatic grief at 6 months after the suicide predicted depression at 12–18 months (odds ratio=1.15, p=0.02), and traumatic grief at 12–18 months predicted depression at 36 months (odds ratio=1.16, p<0.01). A backward stepwise regression was conducted to predict depression at 12–18 months. Traumatic grief, factor 2, and depression at 6 months were entered into the equation. When factor 2 was removed, traumatic grief at 6 months remained a significant predictor, even when depression at 6 months was controlled (odds ratio=1.18, p=0.02). Similarly, traumatic grief at 12–18 months remained a significant predictor for depression at 36 months when factor 2 was removed from the equation and depression at 12–18 months was controlled for.

Traumatic Grief and PTSD

Of the subjects who met diagnostic criteria for PTSD 1 month after the suicide (N=27), three subjects continued to meet criteria for PTSD at the 6-month assessment. Only one of the three subjects who met criteria for PTSD at 6 months also met criteria for traumatic grief at 6, 12–18, and 36 months. Thus, traumatic grief and PTSD did not overlap in the same subjects all the time. The numbers here are very small for any meaningful statistical testing of the likelihood of subjects with and without PTSD to develop traumatic grief, and the effect size is negligible (0.04).

Among the subjects with traumatic grief, 41.7%, 50.0%, and 22.2% also had PTSD at 6, 12–18, and 36 months, respectively. Pearson correlations between scores on the traumatic grief factor and scores on the PTSD Reaction Index at 6, 12–18, and 36 months were 0.50 (p<0.001), 0.61 (p<0.001), and 0.43 (p<0.001), respectively.

Traumatic grief at 6 months was also a significant predictor of PTSD at 12–18 months when factor 2 was removed from the equation and PTSD at 6 months was controlled for (odds ratio=1.3, p=0.04).

Discussion

In this longitudinal study of bereaved adolescents, we identified a cluster of symptoms that corresponded to traumatic grief. Symptoms of yearning, crying, numbness, preoccupation with the deceased, functional impairment, and poor adjustment to the loss constituted this cluster. Traumatic grief was independent of depression despite the comorbidity of traumatic grief and depression in a substantial proportion of subjects. Depressed and nondepressed subjects were equally likely to develop traumatic grief. Also, traumatic grief and PTSD did not always overlap in the same subjects. Traumatic grief predicted the onset or course of depression and PTSD at follow-up, even after control for depression and PTSD at baseline. These results suggest the distinctiveness of traumatic grief from depression and PTSD among adolescents exposed to suicide.

This study should be considered within the context of its limitations. The study group consisted of friends and acquaintances of suicide victims. The participants had high rates of previous psychiatric history and thus were at high risk for the psychological consequences of bereavement. Also, these were friends and acquaintances of the suicide victim, and their grief reactions might not be representative of adolescents bereaved by the death of other loved ones (parent, sibling, etc.) or due to loss from other causes of death. We would have liked to have a more detailed assessment of grief reactions to explore the occurrence of other symptoms (intrusive thoughts, guilt and self-blame, bitterness and anger, change in world view, etc.) reported to occur among bereaved subjects. Also, an assessment of grief reactions directly after the suicide (e.g., within 2 months) is needed to understand the onset and course of traumatic grief. A separate assessment of significant or prolonged functional impairment would have allowed us to examine whether high scores for traumatic grief are associated with functional impairment beyond that resulting from comorbidity with depression and PTSD. The age range of subjects in this study is wide, ranging from 18 to 23 years, which may have accounted for variations in traumatic grief reactions as well as other comorbid diagnoses. However, when we examined this possibility, no statistically significant differences were found in traumatic grief, depression, and PTSD by age at 6, 12–18, and 36 months. The design of the study was to interview peers at 6 months, as it is considered an appropriate time frame to interview bereaved subjects and to conduct 1-year and 3-year follow-up assessments. The wide time variation in the second assessment (12–18 months) after the initial interview was because many adolescents turned 18 or more and moved away, and thus we had to identify their new addresses. A change in the status of subjects at the second assessment in terms of outcomes could have resulted from this time variation. We examined whether time to the second assessment predicted the risk of traumatic grief, depression, and PTSD and found no significant effect, i.e., the time to the second assessment did not affect the risk of these outcomes. The ethnic homogeneity of the group limited the generalizability of these results to other ethnic groups.

The traumatic grief factor obtained in this study is qualitatively similar to the complicated grief factor described by Prigerson and colleagues

(17) in their study of the distinctiveness of complicated grief from bereavement-related depression among adults. Symptoms of crying, yearning, and preoccupation with thoughts of the deceased also loaded on the complicated grief factor that they described. Our traumatic grief factor is also qualitatively similar to the published traumatic grief consensus criteria

(21). Specifically, our traumatic grief factor included items of numbness, intrusive thoughts, preoccupation with the deceased, yearning, or sighing, but it did not include avoidance items.

Scores on our traumatic grief factor were significantly correlated with scores on the Inventory of Complicated Grief administered 6 years after the suicide exposure. This provides further evidence that the grief factor identified in this analysis reflects a traumatic grief reaction. The correlation between the Texas Revised Inventory of Grief and the Inventory of Complicated Grief reported in the literature is 0.87 (p<0.001)

(27). Our correlations were lower, probably because of the 3–6-year time differences between the two measures.

Mean scores on the traumatic grief factor in our study decreased significantly at 12–18 months, after which no significant change in scores was observed. In their study, Prigerson and colleagues

(17) found the intensity of traumatic grief to peak 6 months after bereavement and to remain high 25 months and beyond

(20). Although our finding is inconsistent with the finding of Prigerson et al., it is in accordance with the 2-month duration criterion recommended in the published consensus criteria of traumatic grief

(21). The difference between our finding and that of Prigerson et al. could be attributed to the nature of the relationship between the bereaved and the deceased. Friends and acquaintances of suicide victims were examined in this study, whereas bereaved elderly spouses were assessed in the study by Prigerson et al. The course of traumatic grief among bereaved adolescents might also be different from that observed among the elderly.

This group of adolescents is a high-risk group that showed increased rates of any psychiatric disorder, major depressive disorder, any anxiety disorder, substance abuse, conduct disorder, and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder when compared to a demographically matched community-based comparison group. They also showed increased rates of new-onset major depression and PTSD at baseline and follow-up assessments in relation to the comparison group. These findings were reported in a series of publications by Brent and colleagues

(2–

10). Depression and PTSD co-occurred with traumatic grief, an expected finding since bereavement is a common risk factor for all three conditions. The rates of depression and PTSD found in this study among adolescents with traumatic grief are close to those reported by Melhem et al.

(32) among adults participating in an exposure-based psychotherapy for traumatic grief in which 52.2% and 30.4% of the subjects were also diagnosed with major depression and PTSD, respectively. Although these diagnostic categories co-occurred, they did not always overlap. Depressed and nondepressed subjects were equally likely to develop traumatic grief at 6 and 12–18 months. We were not able to statistically test the likelihood of developing traumatic grief among subjects with and without PTSD because of the small numbers of subjects who continued to meet criteria or developed PTSD after 1 month of exposure. Traumatic grief at baseline predicted the onset or course of depression even after control for depression at baseline and predicted PTSD at 12–18 months, with control for PTSD at baseline. The predictive validity of the traumatic grief factor found in this study is similar to that found by Prigerson and colleagues

(17). These findings provide evidence of the distinctiveness of traumatic grief from bereavement-related depression and PTSD in this group of adolescents.

This study is the first to provide empirical evidence of the distinctiveness of traumatic grief from PTSD. Before this, traumatic grief had only been theoretically distinguished from PTSD

(21). Traumatic grief, as defined by the proposed consensus criteria

(21), and PTSD are similar in that both are stress response syndromes. They share symptoms of intrusive thoughts, emotional numbness, detachment from others, irritability, and anger. However, the two disorders are different in several aspects:

1) Traumatic grief includes a prominent component of separation distress characterized by yearning and searching and frequent “bittersweet” recollections of the person who died. Individuals with traumatic grief often believe that grief keeps them connected to the deceased and/or that to grieve less would be a betrayal of the person who died. These symptoms are not seen with PTSD

(21).

2) Hypervigilance in traumatic grief refers to searching the environment for cues of the deceased, whereas in PTSD, it refers to fears that the traumatic event will be reexperienced

(21).

3) Sadness is the predominant affect in traumatic grief, whereas fear is foremost in PTSD.

4) While PTSD diagnostic criteria include sleep disturbance as one of the symptoms, no evidence of hyperaroused sleep is found among subjects with traumatic grief

(33).

This study is the first that we are aware of to look at traumatic grief among adolescents. Adolescents grieve and experience complications similar to adults after bereavement. They also develop a similar traumatic grief reaction. Future studies looking at bereavement among adolescents should not only focus on depression and other DSM diagnoses as the pathology after bereavement but should also examine the signs and symptoms of traumatic grief. Further research is needed to replicate our findings and further establish the validity of traumatic grief syndrome and its temporal course in this age group. More work is also needed on the comorbidity and distinctiveness of traumatic grief, depression, and PTSD among children and adolescents. Meanwhile, we would like to alert clinicians to the occurrence of traumatic grief reactions among adolescents and the need to assess these reactions and address them in their treatment approaches.