Two agents, extended-release venlafaxine

(4,

5) and paroxetine

(6), have demonstrated efficacy in generalized anxiety disorder. Both drugs significantly improve scores on the psychic factor of the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale

(7), while neither has consistently demonstrated significant efficacy on the somatic factor. Previous research indicates that buspirone

(8,

9) and other antidepressants with serotonergic activity, such as imipramine and trazodone

(10), also show greater improvement of psychic anxiety symptoms than somatic symptoms. In contrast, treatment of generalized anxiety disorder with benzodiazepines is associated with greater improvement in somatic than psychic anxiety symptoms

(8,

10). Although the DSM-IV criteria emphasize the importance of psychic anxiety symptoms for the purpose of diagnosis, somatic anxiety symptoms contribute significantly to the clinical presentation and distress associated with generalized anxiety disorder

(11).

Sertraline has demonstrated efficacy across a broad spectrum of anxiety disorders, such as obsessive-compulsive disorder

(12,

13), panic disorder

(14,

15), posttraumatic stress disorder

(16), and social anxiety disorder

(17,

18), but to our knowledge has not yet been tested for generalized anxiety disorder in adults. A placebo-controlled pilot study in children under age 18 years demonstrated significant efficacy for sertraline in generalized anxiety disorder, including effect sizes greater than 1 on both the psychic and somatic factors of the Hamilton anxiety scale

(19).

The current study was undertaken to test the null hypothesis that there is no significant difference in efficacy between sertraline and placebo in the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder when the Hamilton anxiety scale total score is used as the primary efficacy measure. The secondary null hypotheses were that sertraline would show no significantly greater efficacy than placebo in improving the following clinically important dimensions of anxiety: 1) both psychic and somatic symptoms of generalized anxiety disorder as measured by the two factors of the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale

(7), 2) quality of life and functioning as measured by the Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire

(20) and the Endicott Work Productivity Scale

(21), 3) perceptions of health as measured by a visual analogue scale, 4) subjective anxiety and depressive symptoms as measured by the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale

(22), and 5) global severity and improvement as measured by the Clinical Global Impression (CGI) severity and improvement scales

(23).

Method

Study Design

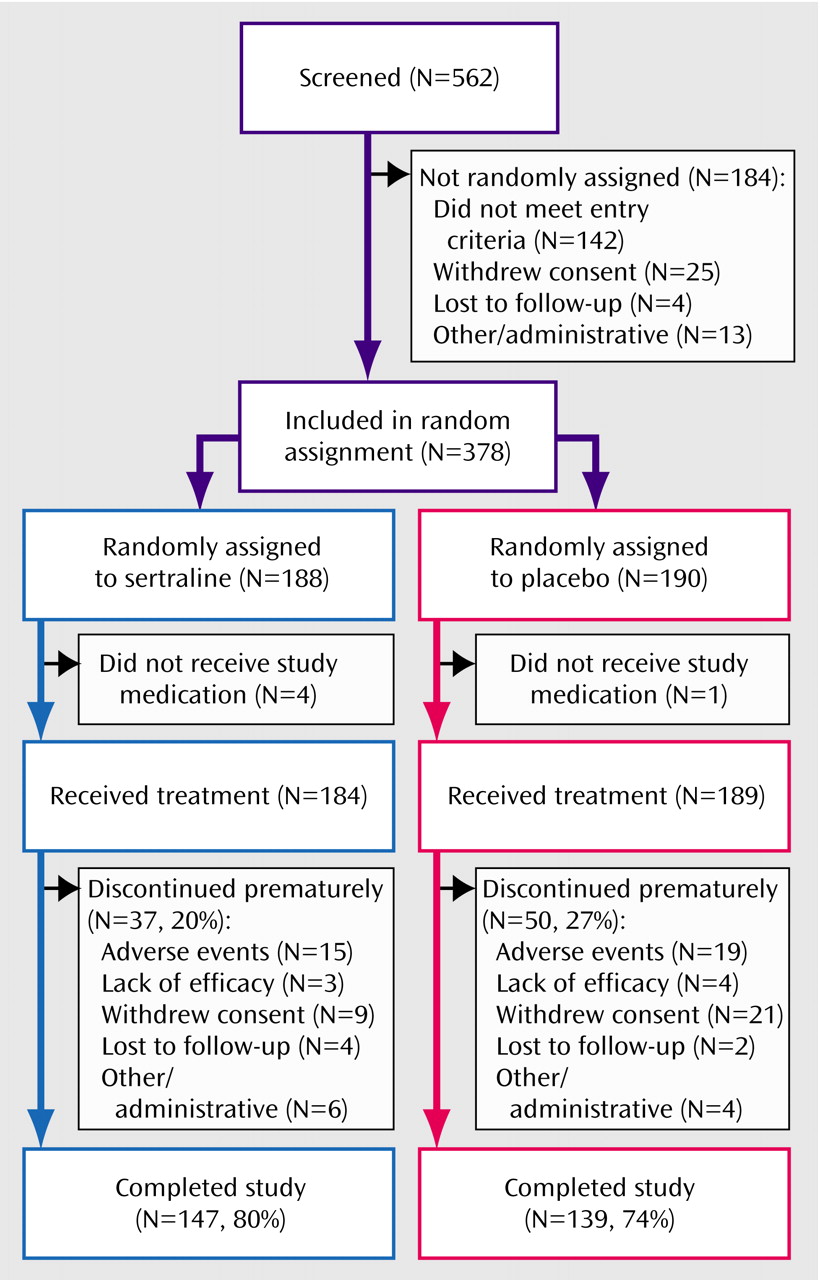

This was a double-blind, placebo-controlled study comparing the efficacy and tolerability of flexible doses of sertraline to placebo in the treatment of moderate to severe generalized anxiety disorder. After completing a 1-week single-blind placebo lead-in period, patients who met the eligibility criteria were randomly assigned to 12 weeks of double-blind treatment with either sertraline or placebo.

Sertraline treatment was initiated at 25 mg/day for the first week, followed by 3 weeks of treatment with a dose of 50 mg daily. From week 5 through week 6, flexible dosing was permitted in the range of 50–100 mg/day, increasing from week 7 through week 12 to a range of 50–150 mg/day. At week 12 sertraline was blindly discontinued, abruptly for patients taking 1 capsule (50 mg) per day. For patients taking a 100-mg dose, it was reduced to 50 mg for 7 days before discontinuation. For patients taking a 150-mg dose, it was reduced to 100 mg for 3 days and then to 50 mg daily for 4 days before discontinuation.

The study was conducted at 21 investigational sites in Australia, Canada, Denmark, Norway, and Sweden. The protocol was approved at each site by the appropriate institutional review board, and written informed consent was obtained from each patient before enrollment.

Patient Selection

Patients were recruited from clinic referrals and from advertisements in local media. Male or female outpatients were eligible for entry if they were 18 years or older and had a primary diagnosis of DSM-IV-defined generalized anxiety disorder based on clinical assessments and a structured interview (module P form of the MINI-PLUS, version 5.0.0

[24]). Patients were also required to have screening and baseline scores of 18 or higher on the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale

(7) and scores of 2 or higher (indicating at least moderate severity) on Hamilton anxiety scale item 1 (anxious mood) and item 2 (tension) at screening and at baseline.

Key exclusion criteria were 1) no current use of medically accepted contraception in fertile women, 2) current or past history of bipolar, schizophrenic, psychotic, or obsessive-compulsive disorder, 3) current history (past 6 months) of major depressive disorder, dysthymia, social anxiety disorder, panic disorder (or three or more reported panic attacks in the previous month), posttraumatic stress disorder, body dysmorphic disorder, eating disorder, or substance dependence and/or abuse, 4) a score of 16 or higher on the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale

(25), 5) concurrent psychotherapy specifically for generalized anxiety disorder, 6) any clinically significant acute or unstable medical condition, 7) positive result from a urine drug and substance screen (including benzodiazepines), 8) treatment with any drug with psychotropic activity (other than infrequent use of chloral hydrate, zolpidem, or zopiclone for insomnia) either concomitantly or within 2 weeks of random assignment (3 weeks for monoamine oxidase inhibitors, 5 weeks for fluoxetine), 9) current suicidal risk, and 10) previous failure to respond to an adequate trial of antidepressant drug treatment (4 weeks at the minimum effective daily dose) for generalized anxiety disorder.

The screening evaluation consisted of a psychiatric and medical history, including physical examination, electrocardiogram, and standard laboratory testing. A urine benzodiazepine screening test was performed both at the baseline visit (in accordance with the exclusion criteria) and after 2 weeks of double-blind treatment (visit 2).

Efficacy Measures

The primary efficacy measure was the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale

(7). This assessment was performed at the screening and baseline visits and at study weeks 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, and 12. The secondary efficacy measures included the following investigator-rated scales: 1) the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale

(25) and 2) the CGI severity and improvement scales

(23). The secondary efficacy measures also included the following patient-rated scales: 1) the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale

(22), 2) the Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire

(20), 3) the Endicott Work Productivity Scale

(21), part I and part II (completed only by patients currently employed or performing volunteer work), and 4) a visual analogue scale measuring perceived state of health.

Safety and Tolerability Measures

Spontaneously reported or observed adverse events were recorded, regardless of causality, in terms of time of onset, severity, action taken, suspected causal relationship, and outcome. Use of concomitant medications was recorded in terms of daily dose, stop and start dates, and reason for use.

Statistical Analyses

A patient was included in the intent-to-treat analysis if he or she had taken at least one dose of study medication during double-blind conditions and had been assessed at baseline and at least once after baseline for the primary efficacy measure. A patient was included in the safety analysis if he or she had taken at least one dose of study medication.

It was expected that patients treated with sertraline would show greater reductions in scores on the Hamilton anxiety scale than would placebo patients and that the difference would be statistically significant. Based on previously reported studies of SSRIs in the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder

(4), an intent-to-treat group size of 185 per treatment was estimated, at an experiment-wise alpha level of 0.05, in order to provide 85% statistical power to detect a mean difference in endpoint change scores on the Hamilton anxiety scale of 2.6 with a standard deviation of 8.1. This was based on the assumption that 10% of the randomly assigned patients would not return for at least one postrandomization visit and, therefore, would not qualify for the intent-to-treat analysis.

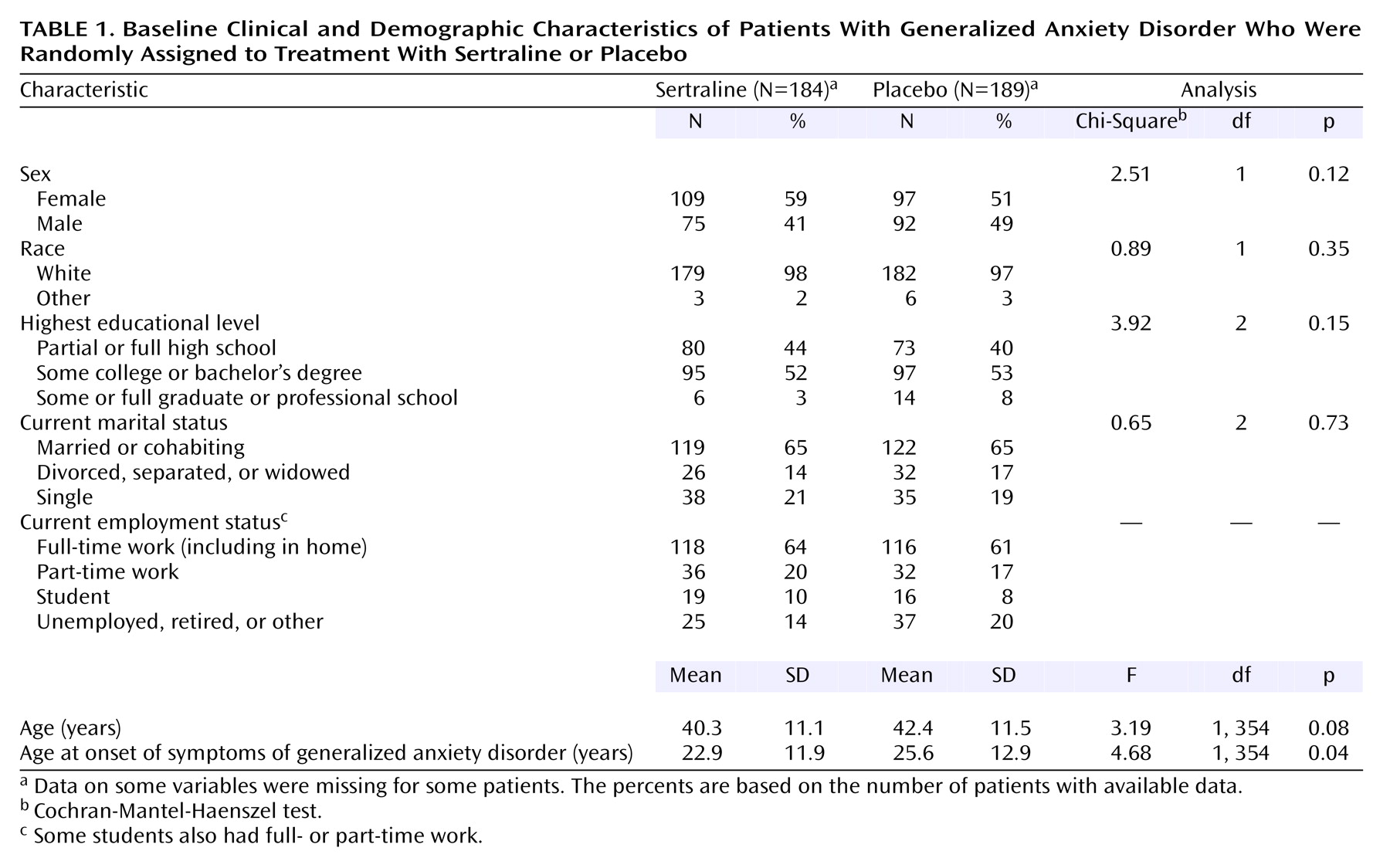

Demographic and baseline characteristics were summarized by using descriptive statistics for continuous variables and frequency counts (and percentages) for discrete variables. Analyses for comparing the homogeneity of continuous variables were performed by using analysis of variance with treatment and site as effects. Discrete variables were compared by using the Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel chi-square procedure stratified by site.

The primary efficacy measure was the change from baseline to endpoint (week 12 or the last observation carried forward) in the total score on the Hamilton anxiety scale for the patients in the intent-to-treat group. Secondary analysis of the Hamilton anxiety scale and the remaining measures was conducted on the change from baseline at each visit at which the scales were administered (i.e., observed cases), as well as endpoint. For continuous efficacy variables, analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was performed on the change from baseline. The ANCOVA model included terms for site, baseline score, and treatment. Comparisons of the treatment groups on the categorical efficacy variables were made by using the Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel row mean scores test with stratification by site. Since the response levels might not be equally spaced but would have a clear ordering, modified ridit scores were used. In addition, the full model with the treatment-by-site interaction was assessed by using logistic models, with cumulative logits for ordered categorical responses.

Remission of generalized anxiety disorder was defined as an endpoint total score on the Hamilton anxiety scale of 7 or less

(26). Effect sizes were calculated with endpoint change scores (based on week 12 values or the last observation carried forward); the difference between sertraline and placebo change scores was divided by the square root of the pooled standard deviation of the change scores.

Statistical analyses were performed by using the SAS statistical package, version 6.12 (Cary, N.C., SAS Institute). Significance levels were set at 0.05 and were two-sided.

Discussion

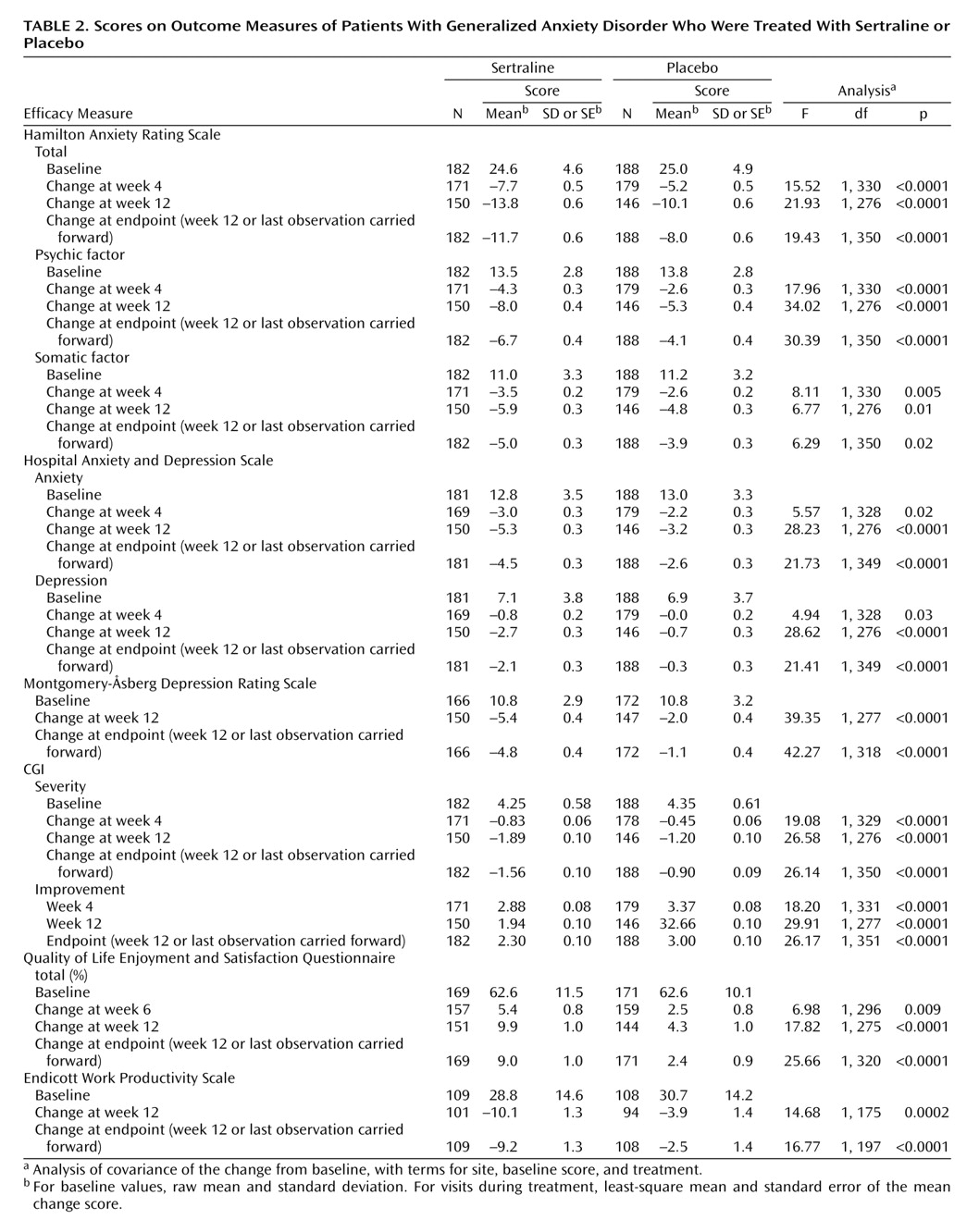

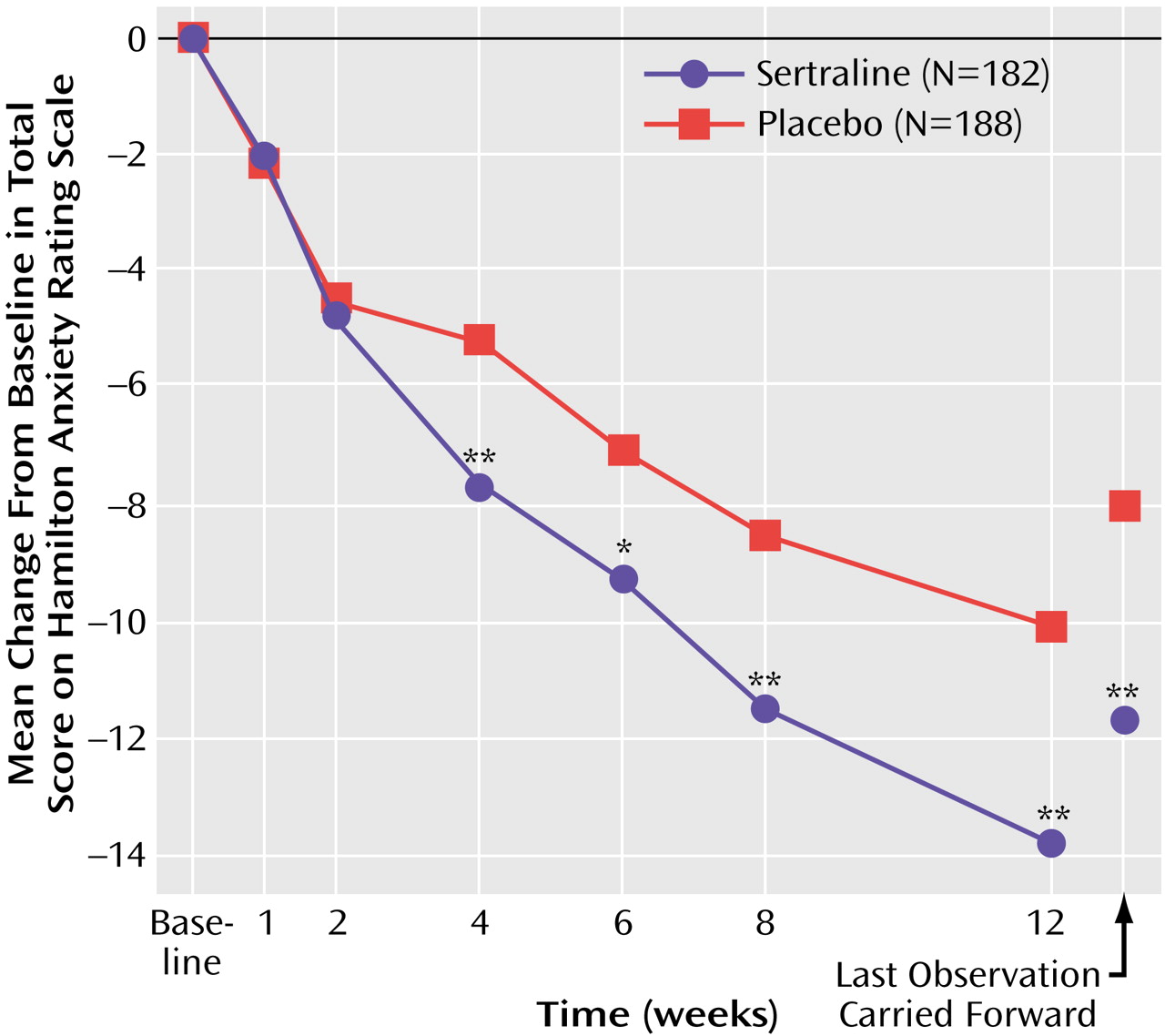

This 12-week double-blind trial showed that sertraline, in daily doses of 50–150 mg, has significantly greater efficacy than placebo in the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder. The anxiolytic response to sertraline was achieved by week 4 and was notable for its efficacy across all primary and secondary outcome measures, including the psychic and somatic anxiety factors of the Hamilton anxiety scale (

Table 2).

The significantly greater efficacy of sertraline, compared to placebo, in improving scores on the psychic factor of the Hamilton anxiety scale is consistent with published reports for paroxetine

(6) and extended-release venlafaxine

(4,

5,

27) in generalized anxiety disorder. SSRIs, and most other drugs that act by modulating serotonergic neurotransmission (e.g., buspirone, trazodone, imipramine)

(8–

11), have consistently demonstrated greater short-term efficacy for improving psychic symptoms of anxiety than for somatic symptoms. This is especially evident from a meta-analysis of the item-by-item efficacy of extended-release venlafaxine

(28), although the greater efficacy of paroxetine for short-term psychic anxiety demonstrates the same pattern

(6). In contrast, the published literature suggests that benzodiazepines have greater efficacy for improving somatic symptoms of anxiety than for psychic symptoms

(8–

11). It is interesting that psychotherapy, especially cognitive behavior therapy, has also been shown in controlled trials to be effective in treating generalized anxiety disorder, with comparable improvement in both psychic and somatic symptoms

(29).

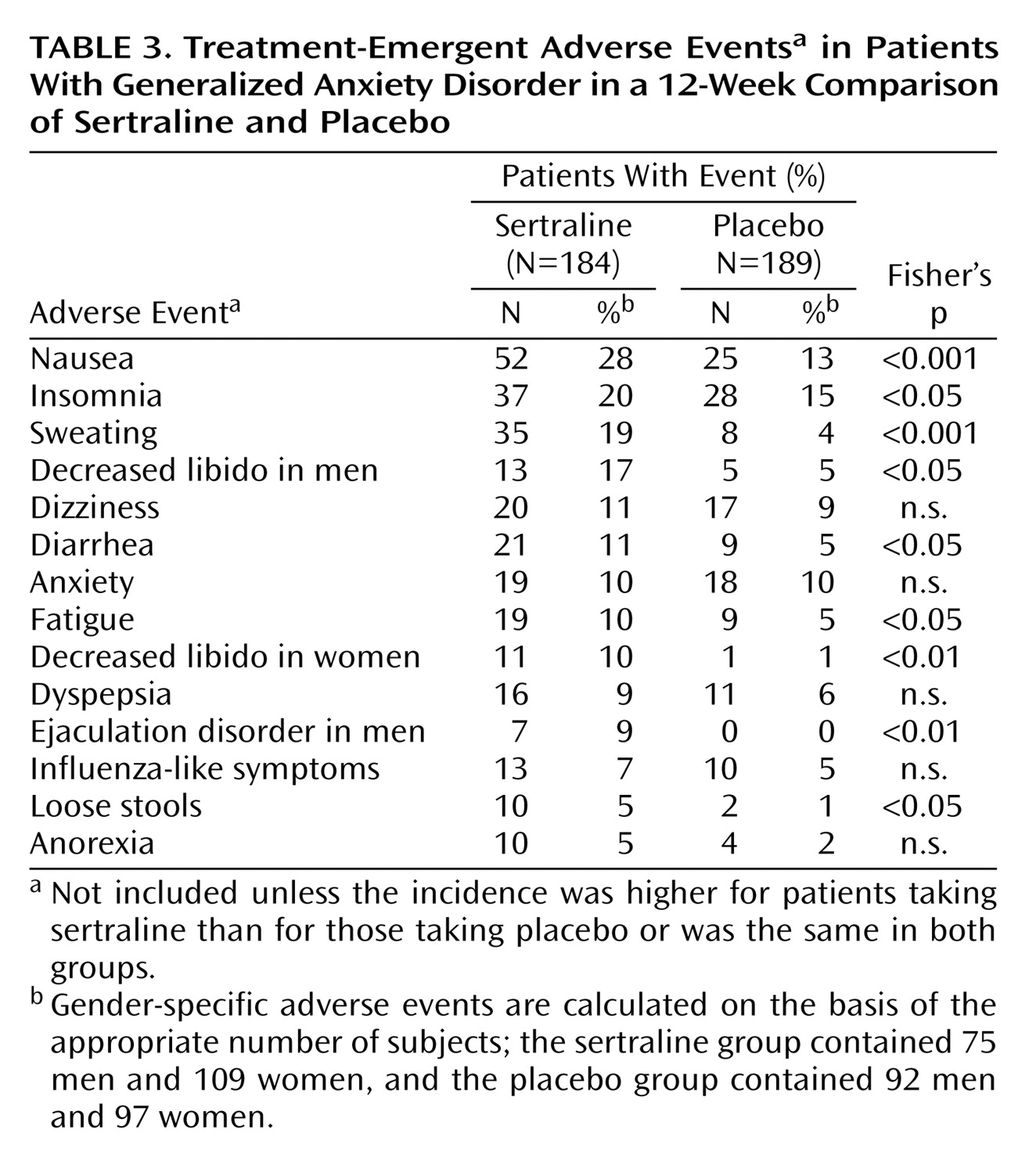

The finding in the current study that sertraline has significantly greater short-term efficacy than placebo in the treatment of somatic anxiety, as measured by the somatic anxiety factor of the Hamilton anxiety scale, is consistent with similar data from a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of sertraline in children and adolescents with generalized anxiety disorder

(19). It should be noted that the incidence of treatment-emergent somatic symptoms (e.g., nausea, diarrhea, sweating), while relatively modest, nonetheless appears to have reduced the magnitude of the average improvement in the somatic anxiety score. This is similar to what is observed in depression studies, in which the magnitude of state-dependent improvement with SSRIs in sleep and sexual dysfunction, as shown by group mean change scores at endpoint, is also reduced by treatment-emergent adverse events in a minority of patients.

Whether sertraline offers an advantage in effectively treating somatic anxiety symptoms needs to be confirmed by additional studies. Regardless, it is important to note that the somatic cluster of anxiety symptoms contributes significantly to the clinical presentation of generalized anxiety disorder and to the distress and disability associated with this diagnosis, even though these symptoms may have less utility as diagnostic criteria

(11, DSM-IV-TR). This was illustrated in the current study by the fact that somatic symptoms contributed more than 40% to the total symptom burden, as reflected in the Hamilton anxiety scale total score at baseline. This somatic contribution to generalized anxiety disorder is consistent with data from other studies of the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder

(4–

6,

8,

27).

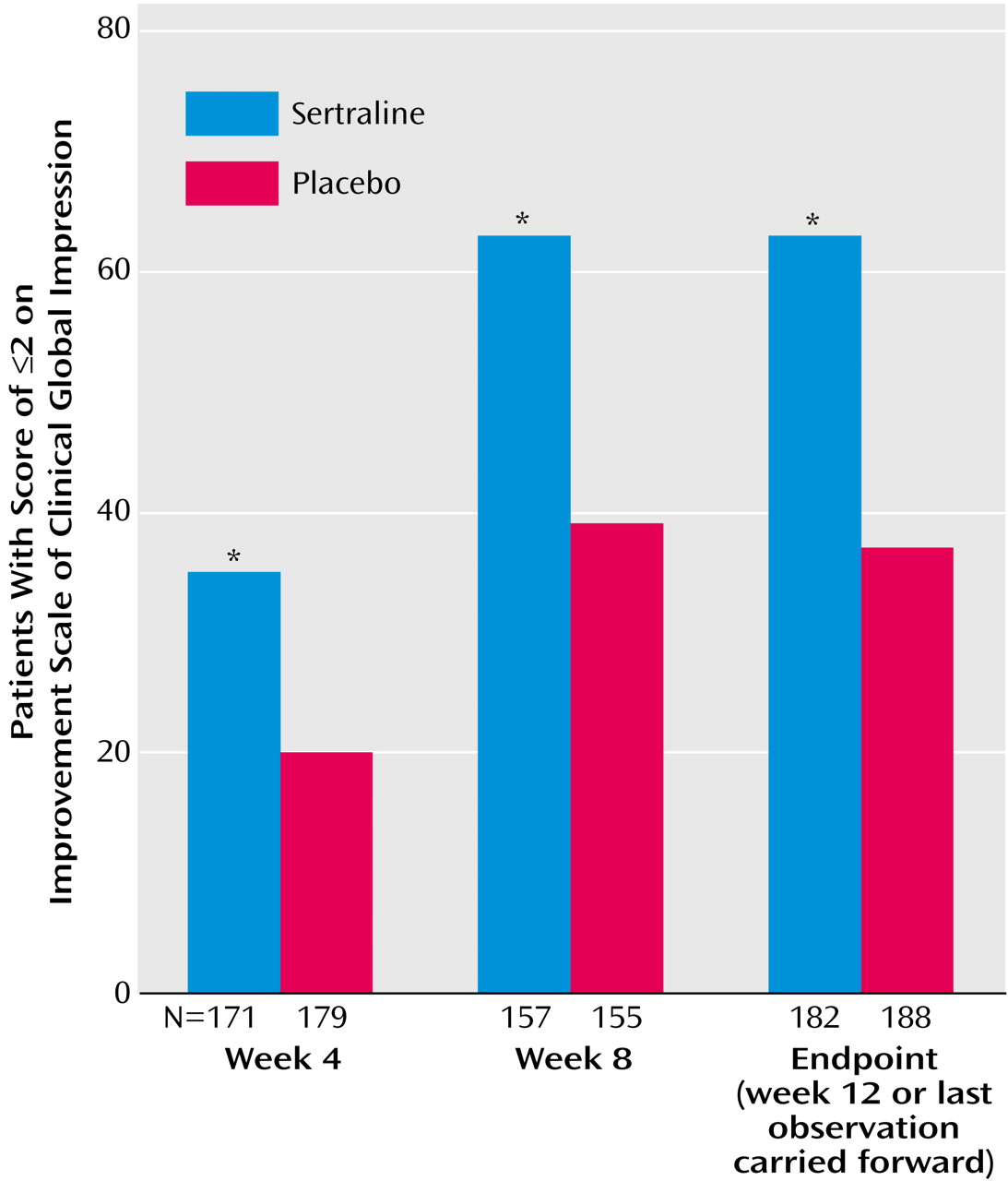

In the current study, the magnitude of the improvement in the Hamilton anxiety scale total score at week 12 (or last observation carried forward) with sertraline relative to placebo (approximately 12 versus 8 points) is comparable to what has been reported in the two studies of extended-release venlafaxine with week 12 data

(4,

5). The two published studies of paroxetine

(6,

30) are difficult to compare because they were 8 weeks in duration and because the placebo response rates were relatively high in both studies (45% and 47% according to analyses with the last observation carried forward and with the response criterion based on the CGI improvement scale score). In the current study, the placebo response rate at endpoint (week 12 or the last observation carried forward) for placebo was 37%, according to the CGI improvement scale criterion, compared to 63% for sertraline. It is interesting that applying an illness-specific criterion (i.e., ≥50% reduction in Hamilton anxiety scale total score) to the response at endpoint yielded a more conservative estimate of treatment effect (56% versus 29%) (Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel χ

2=26.74, df=1, p<0.001) but one with a higher odds ratio in favor of sertraline over placebo.

The rate of remission at endpoint (with the last observation carried forward) was 31% for sertraline (versus 18% for placebo), while the remission rate among completers was 37% (versus 23% for placebo). The results achieved after short-term sertraline treatment are notable given the baseline severity (mean Hamilton anxiety scale score, 25) and chronicity (15–20 years) of generalized anxiety disorder in the current study group. Obtaining these remission rates for sertraline within 3 months is notable, in comparison to a naturalistic follow-up study of patients with generalized anxiety disorder treated in a psychiatric setting, in whom remission occurred in 38%, even after 5 years

(31). The sertraline remission rates may be cautiously placed within the context of short-term remission results from two previously published flexible-dose studies of extended-release venlafaxine

(32) and paroxetine

(6). In both studies the baseline Hamilton anxiety scale scores and illness durations were similar to those in the current study. The rate of remission at endpoint in the trial of extended-release venlafaxine (week 8 or the last observation carried forward) was 32% (versus 15% for placebo), while the rate of remission at endpoint in the paroxetine study was 36% (versus 23% for placebo). The sertraline versus placebo effect size for remission in the current study was similar to what was reported for both extended-release venlafaxine and paroxetine.

Improvement with sertraline in the symptoms of generalized anxiety disorder was associated with parallel improvement in scores on the secondary anxiety and depression measures, such as the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale and the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (

Table 2). It is of interest that the patient-rated Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale anxiety and depression subscales, respectively, were as sensitive to the anxiolytic and antidepressant effects of sertraline as the investigator-rated Hamilton anxiety scale and Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale.

Symptom reduction after short-term treatment with sertraline rapidly resulted in significant improvement in both quality of life and work productivity (

Table 2). The baseline score of 63% on the Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire in the current study suggests that these patients with generalized anxiety disorder had a degree of impairment in quality of life that is equivalent to what has been reported in similar treatment groups with major depression and greater than in patients with social anxiety and panic disorder

(33,

34).

Treatment with sertraline was well tolerated, with a pattern of adverse events that was similar to what has previously been reported in studies of sertraline for the treatment of depression and anxiety disorders. Six adverse events were rated as severe by more 3% of the patients. Confirming sertraline’s tolerability was the similarity in the rates of discontinuations due to adverse events for sertraline (8%) and placebo (10%).

The main limitation of the current study, which is shared by most recent placebo-controlled trials for anxiety disorders, is the exclusion of patients with comorbid major depressive disorder. This is perhaps of less concern with sertraline, given its established efficacy in major depressive disorder, as well as recent evidence for efficacy in comorbid major depressive disorder and panic disorder

(35).

In conclusion, the results of this 12-week treatment study demonstrate that sertraline is an effective and well-tolerated treatment of generalized anxiety disorder. This anxiolytic benefit extends to both psychic and somatic anxiety symptoms. Furthermore, symptomatic improvement is associated with parallel improvement in quality of life and occupational functioning.

Acknowledgments

In Australia the principal investigators were David Barton, M.D., Melbourne, Victoria; Phillip Boyce, M.D., Penrith, New South Wales; Philip L.P. Morris, M.D., Ph.D., Southport, Queensland; and John Tiller, M.D., Melbourne, Victoria. In Canada the principal investigators were Richard Bergeron, M.D., Hull, Quebec; Yves Chaput, M.D., Saint-Jean-Sur-Le-Richelieu, Quebec; Stan P. Kutcher, M.D., Halifax, Nova Scotia; Arumuga Ravindran, M.D., Ottawa, Ontario; and Meir Steiner, M.D., Hamilton, Ontario. In Denmark the principal investigators were Kirsten Behnke, M.D., Frederiksberg; Flemming Bjorndal, M.D., Greve; Peter Ostergaard, M.D., Middelfart; and Jesper A. Sogaard, M.D., Kalundborg. In Norway the principal investigators were Marit Bjartveit-Krüger, M.D., Levanger; Alv A. Dahl, M.D., Oslo; Ingrid Østby-Deglum, M.D., Ottestad; and Torbjørn Sigurdson, M.D., Trondheim. In Sweden the principal investigators were Christer Allgulander, M.D., Huddinge; Goran Björling, M.D., Trollhattan; Anna Loewenstein, M.D., Göteborg; and Ingemar Sjodin, M.D., Linkoping.